1. Background

Individuals use the Internet for various purposes, such as shopping, communicating with others, following the news, making bank payments, and booking travel tickets, hotels, and cinemas (1). These uses have become an essential part of individuals’ daily life. During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, the role of the Internet and social networks increased (2), and all students in Iran had to use the Internet to attend classes (3). Other individuals have been using the Internet for similar reasons, communicating and following the news (4). Therefore, the daily use of the Internet has become more widespread.

Using the internet might cause pathological behaviors and severe psychological problems (5). One of the most researched topics in this area is internet addiction, which Young conceptualized in 1998 (6). Then, this addiction was divided into different types, namely social network addiction (7) and video game addiction (8). Social network addiction, which began with the advent of the first generation of social media, showed individuals’ strong desire for frequent, excessive, and compulsive social network use (7), which led to psychological problems, such as depression (9), anxiety (9), and interpersonal relationship issues (10). Of related concepts in this area, fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing can be mentioned.

1.1. Fear of Missing out

Some researchers have focused on the motivations for using social networks and have mentioned the concept of FoMO as an important motivation for individuals to use social networks (11). The FoMO can be defined as a person’s fear of not being present in the rewarding experiences that others might have (11). Research has shown that FoMO can be one of the reasons for individuals’ participation and presence in social networks (12). The FoMO forces individuals to constantly check and know more about what others are doing (13). Therefore, this issue can affect their psychological well-being and behavior. Research on the motivations for using the Internet has shown that individuals are forced to use the Internet to avoid negative moods, such as loneliness and boredom (13). In this regard, a person’s dissatisfaction with the current relationship can also affect compulsive use of the Internet and FoMO (14). Research on FoMO and social network addiction, depression, and anxiety has pointed to the mediating role of FoMO in the pathological use of smartphones and social media addiction (15). A recent meta-analysis addresses the level of FoMO associated with social media use and the pathological use of social media (16).

It has been shown that FoMO is related to mental health and well-being (17). A combination of FoMO and the excessive use of social media is associated with anxiety and depression (15). Wegmann et al. studied FoMO as a personality trait or a state (18). They consider the trait of FoMO as a personality trait to indicate a person’s overall FoMO on something. They consider the FoMO a complex and multidimensional structure that includes the trait-FoMO and the state-FoMO. Trait-FoMO refers to stable personal characteristics, and state-FoMO refers to online and interactive features (18).

1.2. Phubbing

Checking and using smartphones in different situations is common among smartphone users. The word “phubbing” is a combination of “phone” and “snubbing,” which refers to a person who constantly looks at his/her mobile phone while doing another activity, such as talking to another person; therefore, interpersonal communication would be endangered (19). At present, phubbing has become part of individuals’ daily interactions (1). In a study, 90% of participants reported using their mobile phones during a social conversation (20). Research has shown that this phenomenon can affect relationships negatively (19). Research on the role of phubbing and its effect on romantic relationships has addressed several aspects, including a feeling of jealousy (21), lack of intimacy (22), and low levels of relationship satisfaction (23).

Frequent phubbing in a person’s communication is also associated with high levels of depression (24). Several predictors of phubbing have been identified in various studies, including lack of control (25), FoMO (26), mobile phone addiction, social media addiction (27), and neuroticism (28). Wegmann et al. developed the fear of missing out scale (FoMOs), a 12-item scale for measuring FoMO with two subscales (18). The phubbing scale (TPS) was also developed by Karadag et al. (27) to examine phubbing behaviors among mobile phone users.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the psychometric properties of the FoMOs and TPS among internet users in the Iranian population.

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure

Initially, these two scales were translated into Farsi by two PhD students separately. Then, the two translations were compared in a group discussion, and a consensus was reached on the translations. The Farsi translation was examined by a third party person who was familiar with English and back-translated into English. Two faculty members reviewed the three versions of the translations. Finally, these two scales were modified and approved. The two scales were distributed to 40 internet users to evaluate the pre-test and post-test reliability. The pilot results were then analyzed, and the accuracy of the translations was confirmed for the two scales. After 4 weeks, the scales were repeated on the same 40 respondents to check the test-retest reliability. In the next step, the scales were put on a website. The data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26), Amos software (version 24), descriptive statistical methods, Pearson correlation coefficient, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

3.2. Participants

This study was a cross-sectional descriptive investigation. The statistical population included users of social networks in Iran within May to July 2021. Using the convenience sampling method, 18 - 36-year-old Instagram users completed the scale. The overall sample included 440 respondents, and the sample size was selected based on the number of items on the two scales; for each item, 20 participants were enrolled. A website was created for users to have access to and complete the scales. For sampling, this study used followers of unofficial academic pages of the universities of Tehran, Shiraz, Mashhad, Isfahan, and Urmia, Iran, on Instagram. On these pages, they were asked to “Click on the link placed here and enter the website if you are willing to participate in a study.” Finally, 458 subjects completed the scales; however, 27 respondents were not accepted because they were not within the age range of 18 - 36 years and were excluded from the data analysis process.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. The Fear of Missing out Scale

The FoMOs assesses different levels of FoMO. This scale, developed by Wegmann et al. (18) using Przybylski et al.’s (11) previous FoMOs, has two subscales, namely trait-FoMO, and state-FoMO, which measure different aspects of FoMO. The FoMOs is a 12-item scale that uses a 5-point Likert scale (“never” to “always”). A study conducted on German-speaking subjects showed two-factor in CFA. The reliability of both subscales, including trait-FoMO (α = 0.821) and state-FoMO (α = 0.813), was acceptable.

3.3.2. The Phubbing Scale

The TPS was developed by Karadag et al. in Turkey (27). This scale consists of 10 items, and each item is scored based on a 5-point Likert scale (“never” to “always”). In a study by Karadag et al., EFA showed two subscales, namely communication disturbances and phone obsession (27). This study’s factor analysis and linear regression results confirmed the scale’s validity. The internal consistency of each subscale, including communication disturbances (α = 0.87) and phone obsession (α = 0.85), was acceptable.

3.3.3. Social Network Addiction Test

The Social Network Addiction Test (SNA-T) is an adaptation of the Young Internet Addiction Test, with 20 items based on a 5-point Likert scale (“not applicable” to “always”) (29). This test examines the pathological use of social networks and their severity. The reliability indicators of this questionnaire were appropriate. The scale’s internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was acceptable (α = 0.91).

4. Results

4.1. Description of Participants

A total of 431 subjects participated in this study, 328 (76.1%) and 103 (24.6%) of whom were female and male, respectively. The participants were within the age range of 18 - 36 years, with a mean age of 26.31 ± 4.90 years. The participants’ marital status was reported as 71.2%, 25.8%, 1.4%, and 1.6% for single, married, divorced, and widowed subjects, respectively. The educational status of the participants was reported as 0.7.%, 16.7%, 40.4%, 30.4%, and 11.8% for those under a diploma, diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and PhD and higher, respectively. Regarding using social network sites, 11.6% (n = 50), 37.6% (n = 162), 30.2% (n = 130), 11.1% (n = 46), 5.3% (n = 23), and 4.2% (n = 18) of the respondents spent less than 2 hours, 2 - 4 hours, 4 - 6 hours, 6 - 8 hours, 8 - 10 hours, and more than 8 hours per day, respectively.

4.2. Fear of Missing out Scale

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the FoMOs reported as 0.85. The Cronbach’s alpha was higher than 0.7, indicating that the scale had good internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.83 and 0.80 for trait-FoMO and state-FoMO, respectively.

For assessing the reliability, a test-retest was performed in a 4-week interval between the first and second implementation of the test among 40 samples, and the Pearson correlation was used. The correlation between the test and retest for the overall scale was 0.84. Moreover, the correlation between the test and retest for trait-FoMO and state-FoMO were 0.83 and 0.75, respectively.

For assessing the validity, EFA was performed on the responses on the FoMOs to investigate the factor structure. For this purpose, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index was measured to evaluate the adequacy of the sample size, reported as 0.829, indicating the adequacy of the sample size. Bartlett’s test was also statistically significant (P < 0.001), which showed the assumption of zero correlation between the rejected questions., EFA was performed on the data. Table 1 shows the results of the factors analysis.

| Item No. | Mean ± Standard Deviation | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.45 ± 1.267 | 0.885 | |

| 2 | 2.45 ± 1.241 | 0.893 | |

| 3 | 2.63 ± 1.309 | 0.683 | |

| 4 | 1.61 ± 0.915 | 0.639 | |

| 5 | 2.65 ± 1.252 | 0.521 | |

| 6 | 2.07 ± 1.246 | 0.664 | |

| 7 | 1.63 ± 1.000 | 0.653 | |

| 8 | 1.52 ± 0.889 | 0.750 | |

| 9 | 2.06 ± 1.194 | 0.750 | |

| 10 | 1.58 ± 0.917 | 0.643 | |

| 11 | 2.10 ± 1.150 | 0.666 | |

| 12 | 1.89 ± 1.053 | 0.694 |

Factor Loadings of Fear of Missing out Scale, Means, and Standard Deviations of Items

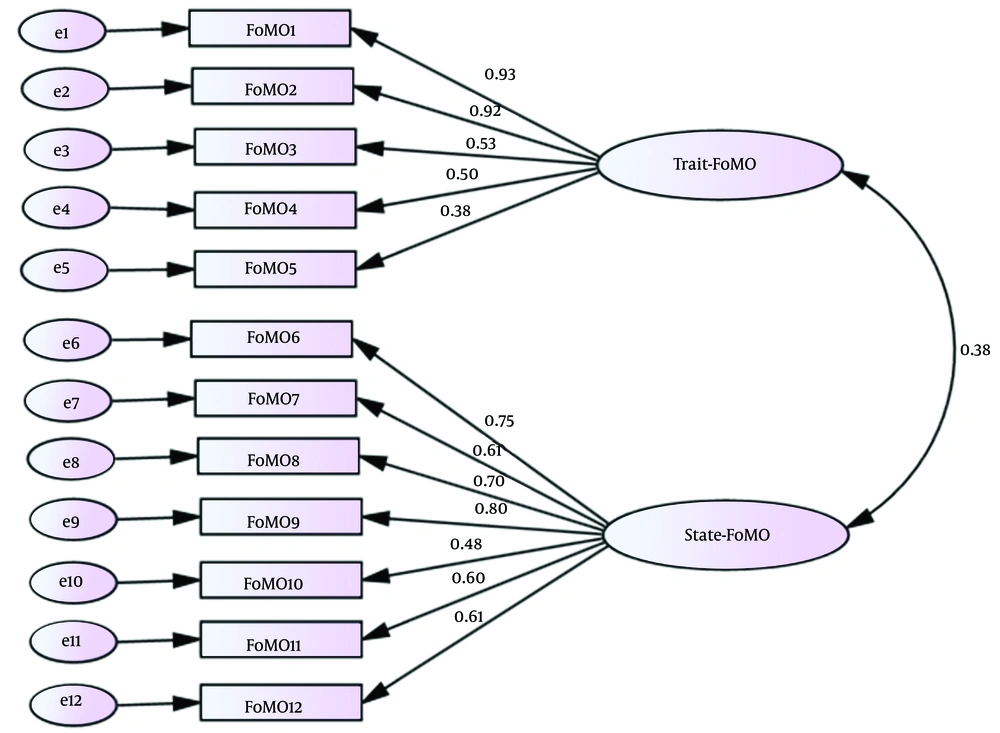

The CFA was used to evaluate construct validity. The purpose of CFA at this stage was to confirm the default factor structure obtained in EFA. For this purpose, a two-factor model of FoMOs was conducted by Amos software. Figure 1 shows the two-factor model of the FoMOs and the results of CFA of the FoMOs, regression weights, and factor loads.

In addition, Table 2 shows the fitness indices of compliance. As shown in Table 2, the values of the chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom, comparative fit index, goodness of fit index, adjusted goodness of fit index, root mean square residual, and root mean square error of approximation in this study for the two-factor model are appropriate for suitable fitness indices’ values. Figure 1 depicts the structure of CFA.

| Index | χ2 | P | χ2/df | CFI | GFI | AGFI | RMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 376.086 | 0.000 | 7.096 | 0.852 | 0.862 | 0.797 | 0.136 | 0.119 |

Results of Goodness of Fit for Fear of Missing out Scale

4.3. Phubbing Scale

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the TPS. Cronbach’s alpha for 10 items of the TPS was 0.83, representing an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha. A 4-week interval between the test and retest was used to evaluate the reliability of the TPS. The correlation between two different times of this scale was 0.86, and the number of participants in this stage was 40.

The EFA was performed to investigate the factor structure of the TPS. The KMO index was reported as 0.829, indicating the sample size’s adequacy. Bartlett’s test was also statistically significant (P < 0.001), which showed the assumption of zero correlation between the rejected questions. Moreover, the conditions for factor analysis were established. Therefore, EFA was performed on the data. Table 3 shows the results of EFA for TPS.

| Item No. | Mean ± Standard Deviation | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.42 ± 1.134 | 0.613 | |

| 2 | 1.79 ± 0.947 | 0.806 | |

| 3 | 1.71 ± 0.959 | 0.810 | |

| 4 | 1.94 ± 0.937 | 0.830 | |

| 5 | 2.17 ± 1.124 | 0.260 | |

| 6 | 3.54 ± 1.307 | 0.761 | |

| 7 | 4.09 ± 1.187 | 0.770 | |

| 8 | 3.29 ± 1.399 | 0.738 | |

| 9 | 2.57 ± 1.338 | 0.507 | |

| 10 | 2.40 ± 1.338 | 0.578 |

Factor Loadings of Phubbing Scale, Means, and Standard Deviations of Items

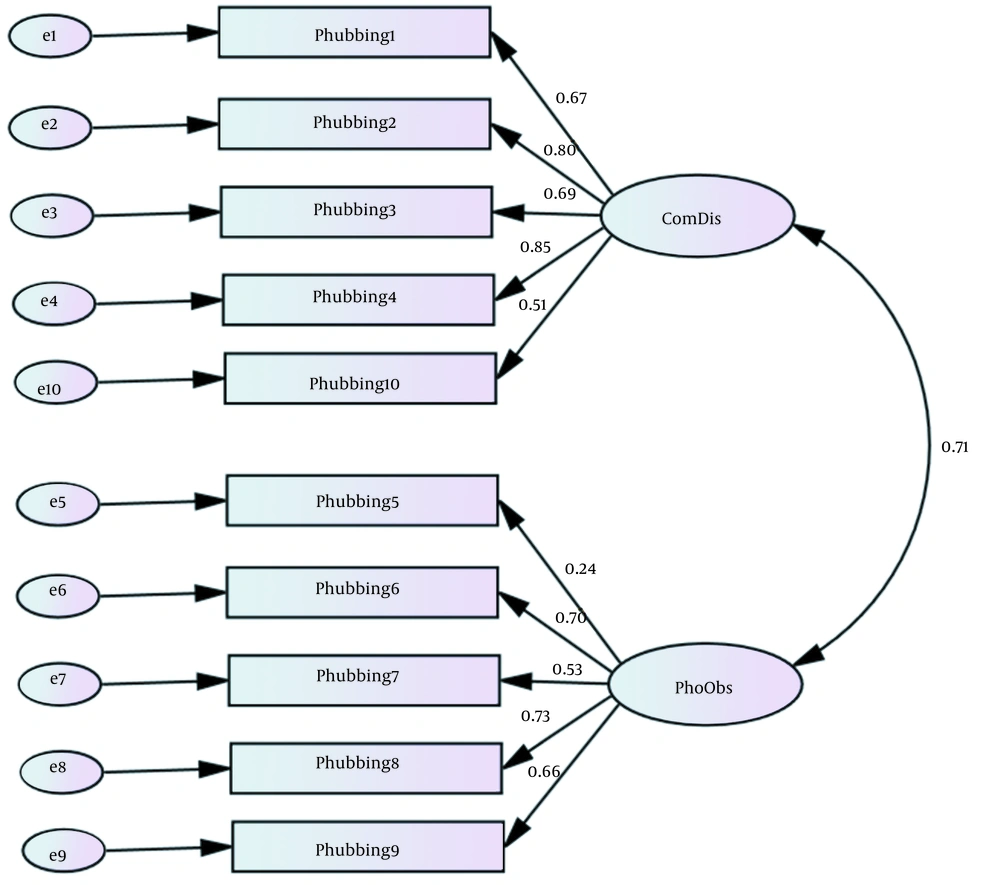

In the next step, the goodness of fit indices were calculated. As shown in Table 4, all indices are acceptable. The values of the indices obtained in Table 4 showed that the two-factor pattern model was appropriate in terms of fit indices. Figure 2 illustrates the graphic figure drawn for the two-factor model of the TPS in Amos software.

| Index | χ2 | P | χ2/df | CFI | GFI | AGFI | RMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 152.917 | 0.000 | 4.498 | 0.919 | 0.934 | 0.893 | 0.097 | 0.090 |

Results of Goodness of Fit for Phubbing Scale

4.4. Concurrent Validity of FoMOs and TPS

In order to evaluate the concurrent validity of the FoMOs and TPS, the simultaneous implementation of these two scales with SNA-T was performed. The results of correlation analysis showed the concurrent validity of the FoMOs (r = 0.51, P < 0.01) and TPS (r = 0.70, P < 0.01). The result showed concurrent validity for both the FoMOs and TPS. In addition, the correlation between the time spent on social networks with TPS (r = 0.45, P < 0.01) and FoMOs (r = 0.21, P < 0.01) was examined. Table 5 shows the correlation between the time spent on social media, SNA-T, TPS (by factors), and FoMOs (by factors).

Correlation Between the Phubbing Scale and Fear of Missing out Scale with Social Network Addiction Test and Time Spent on Social Media

5. Discussion

The FoMO is one of the predictors of internet addiction (30), cell phone addiction (31), and social network addiction (32) and can explain the reason for seeking out an update and engaging in social networks even in dangerous situations, such as driving (33). The FoMOs can measure FoMO in individuals based on trait and state. The present study is the first Farsi investigation in Iran to evaluate this scale’s psychometric properties.

Current research has also cited phubbing as a consequence of internet and social network addiction (27). Phubbing, closely related to social network addiction, can indicate impaired interpersonal relationships, decreased quality of interpersonal relationships, decreased emotional communication, and underlying perceptions of empathy, closeness, trust, and conversation quality (34). The TPS in Iran had previously been standardized; however, in the opinion of the authors of this article, improving the translation and reviewing other issues, such as concurrent validity with social network addiction and the reliability of the test-retest, could improve this scale.

Due to the importance of these two scales, this study aimed to evaluate the validity and reliability of the FoMOs and TPS. The results, reliability, and validity of FoMOs are acceptable and in line with the results of the study of the implementation of this questionnaire in Germany (18). Cronbach’s alpha was reported as 0.85, indicating the internal consistency of the scale items at a reasonable level. The internal consistency of the subscales obtained from this study is not much different from the initial research. Test-retest reliability was also obtained in this study (r = 0.84), indicating the stability of variables on this scale over time. The results of EFA demonstrated the same factors in accordance with the initial scale, and the CFA results also confirmed these factors’ accuracy.

According to the FoMOs, there is a moderate correlation between addiction to social networks and the time spent on social media (r = 0.50 and r = 0.21, respectively). Concurrent validity can be confirmed for the FoMOs. Findings related to the TPS show good reliability and validity, compared to the original version (27) standardized in Turkey. The correlation between the TPS and social network addiction was high (r = 0.70), and the time spent on social networks (0.45) was moderate, indicating a suitable concurrent validity for the TPS. As shown in Table 5, item 5 has a factor loading of 0.26. In the original version, this item was observed to be 0.45, which is not within the acceptable range (> 0.6 or 0.7) in the exploratory model analysis (35). For this reason, this item might be less related to the desired structure. More studies with a larger sample size are needed to remove or edit this item. Therefore, it is suggested to consider removing or replacing this factor in future studies with larger sample sizes.

In this study, the correlation of trait-FoMO with social network addiction was low. It can be inferred that having the trait alone cannot lead to the pathological use of social networks; nevertheless, it is a situation related to FoMO that encourages individuals to pathologically use social networks. Balta et al. pointed to the role of FoMO as a predictor for the problematic use of Instagram (28), which indicates the importance of FoMO in social network addiction.

Regarding the limitations of the present study, using convenience sampling on Instagram can be mentioned. It is suggested to perform further studies to evaluate the role of personality traits in FoMO and phubbing to understand Iranian users’ behaviors on social networks.