1. Background

The victimization issue, especially in adolescence, is a major international problem (1). It is estimated that more than 100 to 600 million adolescents worldwide are directly damaged due to violence each year (2). Moreover, victimization is one of the most important, preventable hazards to adolescents’ health and development worldwide (3-5). In 2014, higher than 1 billion children overall aged 2 - 17 years reported physical, emotional, sexual, or other types of violence (6). Such adverse effects of victimization on children’s short- and long-term emotional, behavioral, and physical health have been consistently documented (7). Historically, studies show that male adolescents are more likely than female adolescents to be victims of peer violence (8, 9). Additionally, victimization might occur in different environments; however, what has been of most interest to educational researchers is victimization in the school environment, which holds semantic proximity to school violence (10). As a pioneer in school bullying, Olweus, as cited by Thornberg et al., defines school bullying as a subset of aggressive behavior (11) that appears as verbal, physical, and relational behaviors (12) and includes three components, namely negative actions, repetition over time, and imbalance of power (13).

The enriched literature related to emotional intelligence (EI) has investigated the effects of EI as one of the most important variables associated with victimization (14-16). The EI is defined as one’s ability to perceive or recognize, understand, handle, and express emotions (17). In short, the EI trait is defined as a system of emotional self-perception placed at lower levels of the personality hierarchy (18). Social intelligence is a more complex form of victimization, and only the kind of bullying that deals more with physical and direct forms shows low social intelligence (18). Individuals with high EI tend to experience better interpersonal relationships and benefit from higher levels of social abilities (19). In a study on 284 adolescents assessing the relationship between EI and victimization, dimensions of EI were found to be significantly correlated with victimization and victim-oriented attitudes. Regression analysis showed that lower emotional understanding, management, control, vacillation, and weaker victim-oriented attitudes were predictors of bullying. The effects of EI and victim-oriented attitudes on victimization have been examined, and independent relationships with lower emotional management and control were obtained regarding the victimization prediction model (20). This means that bullying and victimization were associated with low EI.

Loneliness is another variable associated with victimization in schools (21-24). Cava et al. consider loneliness a cognitive awareness of the weakness of social and personal relationships that leads to sadness, absurdity, and regret (25). Loneliness is the person’s disability in establishing and preserving satisfactory relationships with others, which stimulates deprivation (26). Individuals who are unable to establish and maintain satisfactory relationships with others will have difficulty meeting their belonging needs. They might experience a sense of deprivation that manifests itself with loneliness (27). The research findings suggest the existence of a relationship between victimization and negative psychological consequences, such as low self-esteem, shyness, and isolation (28). Similarly, high levels of anxiety and depression, psychosomatic symptoms, sleep problems, tension, fatigue, and dizziness are actively present in victims of bullying (29).

Empathy is regarded as one of the most important variables associated with victimization. Empathy is defined as the human ability to identify and respond to others’ mental states present from birth, infancy, and childhood (30). The children with a higher level of empathy ooze more kindness and caring behaviors than others, are sensitive and concerned about damage to others, show positive emotions toward others, share positive physical interactions with others, establish positive verbal interactions, and are sensitive to non-verbal interactions (31). A survey was conducted on empathy and victimization, and social behavior was considered to identify 21 social children, 23 bullies, and 14 victims of bullying from a sample of 9- to 10-year-old British students (n = 131). The results showed that social children obtained significantly higher scores in emotional empathy than bullies (32). In addition, bullying behaviors and victimization have been found to be correlated with some EI skills. The studies carried out in this regard have reported a significant relationship between these variables and empathy (33).

In another study wherein the relationship between empathy and bullying was examined, the findings revealed that low emotional empathy was significantly associated with bullying in both male and female adolescents. However, low emotional empathy for both male and female adolescents was related to coping with frequent situational bullying; low levels of total emotional empathy for male adolescents were associated with violent bullying, and low levels of total emotional empathy for female adolescents were associated with indirect bullying (34). Therefore, according to the related literature, foreign researchers have examined victimization in schools and tried to propose suggestions to prevent it. However, no study has been performed in Iran wherein some variables, such as EI, loneliness, and empathy, have been examined together, and their relationships with victimization have been explored.

2. Objectives

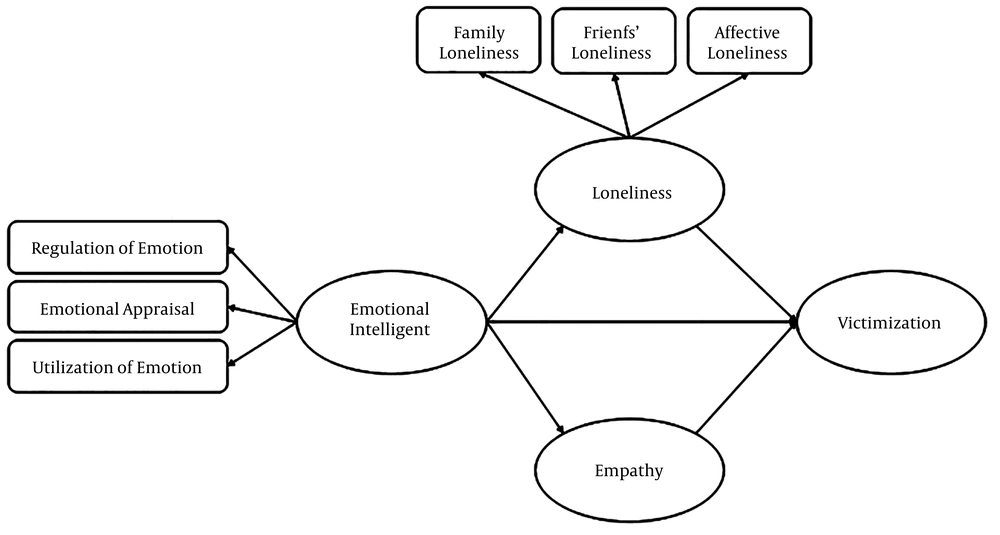

The present study aimed to assess the role of EI, empathy, and loneliness in predicting victimization among senior high school students. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model of the present study.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling Method

A descriptive research design, along with a correlation research type, was used to conduct this study. All male and female students in public high schools of Yasouj, Iran, within 2020 - 2021 constituted the statistical population of this study. Then, three schools were selected from the second municipal area of Yasouj via random cluster sampling. The number of 365 students (150 males and 215 females) was selected based on Morgan’s table. Before administering questionnaires, the required license for their distribution in the schools was obtained, and the informed consent of participants was also obtained. Moreover, the participants were given the assurance about the anonymity of their names. It is noteworthy that there were about 2126 female seventh graders, 2242 female eighth graders, 1730 male seventh graders, and 1840 male eighth graders in that year in Yasouj. For data analysis, mean ± standard deviation, Pearson correlation, and structural equation modeling were applied using SPSS software (version 19) and AMOS software (version 20). The following instruments have been used for data collection:

3.2. Instrument

3.2.1. Victimization Scale

This scale was developed by Orpinas (1993) to measure victimization with ten items that measure victimization as a one-dimensional construct (35). This tool is located on a Likert scale with seven options (zero time = 0 to six times or more = 6). Orpinas (1993) implemented this tool on children aged 10 - 15 years and reported a validity of 0.85 (35). This questionnaire was administered to adolescents in Iran. The results of factor analysis presented the one-factor structure of the instrument with appropriate fit indices. The validity of this scale has been reported as 0.97 (19). Furthermore, in previous studies, the reliability of this questionnaire was evaluated, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.87. Moreover, the reliability of this questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha on the Iranian sample was 0.88 (36). In addition, the validity of this instrument by Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be 0.79 (36).

3.2.2. Loneliness Scale

This scale consists of 38 items completed on a 5-point Likert scale from very high to very low. The instrument has been composed of three dimensions, including loneliness due to relationship with family (items numbered 2, 4, 9, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 32, 33, 35, and 37), loneliness due to relationship with friends (items numbered 1, 3, 5, 10, 11, 15, 19, 21, 30, 31, and 38), and affective symptoms of loneliness (items numbered 6, 7, 8, 13, 17, 22, 27, 28, 34 and 36). Noticeably, some items of the scale are scored in reverse. Furthermore, the reliability of the scale was calculated via Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and test-retest reliability, which were obtained equal to 0.91 and 0.83, respectively (37). In addition, the convergence validity of the scale was obtained through the correlation of the scale with the UCLA Loneliness Scale and Beck Depression Inventory (0.60) (26).

3.2.3. Schulte Emotional Intelligence Scale

This is a 33-item scale that is scored based on a 5-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree to strongly disagree = 1). This instrument assesses EI in a three-dimensional construct. The dimensions comprised appraisal and expression of emotion, regulation of emotion, and utilization of emotion. The designers of this scale reported its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to 0.90. In addition, the reliability coefficients of this scale were obtained using Cronbach’s alpha equal to 0.78, 0.79, 0.75, and 0.64 for the total scale, regulation of emotion, appraisal, expression of emotion, and utilization of emotion, respectively. The convergence validity of this scale was reported as 0.87 (38), and the reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was reported as 0.87 (12).

3.2.4. Baron-Cohen’s Empathy Scale

This scale included 60 items that are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. This instrument enjoys acceptable psychometric properties, and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported to be equal to 0.85 (39, 40).

4. Results

The sample’s age mean score was 13.92 ± 0.78 years. Pearson correlation and structural equation modeling methods were used to investigate the structural model of adolescent victimization based on EI with the mediating role of loneliness and empathy. The general status of the data was examined before performing data analysis. First, the existence of data outside the scope of the study and the necessary corrections were made by referring to the original questionnaires. The unreported data were then examined and found to be unreported. In addition, univariate outline data were analyzed using a box plot, and the results showed that there was no outlier data. In addition, the skewness of the data was calculated using SPSS software, and the results showed that the skewness of any of the values was not more than 1%, which indicated that the data were assumed to be normal. Before examining the modeling results of structural equations, Table 1 shows the correlation matrix related to the variables.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Victimization | 12.85 ± 14.69 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Regulation of emotion | 39.14 ± 6.31 | -0.463 a | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Emotional appraisal | 44.28 ± 6.78 | -0.378 a | 0.536 a | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Utilization of emotion | 36.54 ± 5.87 | -0.493 a | 0.505 a | 0.474 a | 1 | |||||

| 5. Total emotional intelligence | 119.97 ± 16.75 | -0.513 a | 0.571 a | 0.581 a | 0.589 a | 1 | ||||

| 6. Family loneliness | 27.17 ± 16.14 | 0.484 a | -0.408 a | -0.390 a | -0.428 a | -0.512 a | 1 | |||

| 7. Friend loneliness | 20.29 ± 12.68 | 0.464 a | -0.461 a | -0.495 a | -0.445 a | -0.503 a | 0.541 a | 1 | ||

| 8. Affective loneliness | 17.66 ± 8.71 | 0.470 a | -0.377 a | -0.365 a | -0.391 a | -0.440 a | 0.510 a | 0.496 a | 1 | |

| 9. Total loneliness | 65.12 ± 32.70 | 0.559 a | -0.545 a | -0.558 a | -0.503 a | -0.580 a | 0.531 a | 0.537 a | 0.610 a | 1 |

| 10. Empathy | 167.32 ± 27.49 | -0.410 a | 0.418 a | 0.495 a | 0.501 a | 0.533 a | -0.401 a | -0.491 a | -0.334 a | -0.477 a |

a P ≥ 0.01

As can be observed, EI and empathy have a negative and significant relationship with adolescent victimization. Nevertheless, the feeling of loneliness has a negative and significant relationship with being a victim. Table 1 shows other results related to the correlation of the research variables. After examining the correlation of the research variables, the modeling of structural equations was examined. To estimate the model, root mean square error of approximation, standardized root means square residual, comparative fit index, normed fit index, goodness of fit index, and adjusted goodness of fit index were assessed. Table 2 shows the fitness indicators of the final research model.

| Amount | Goodness Indicators | Order |

|---|---|---|

| 12.689 | χ2 | 1 |

| 5 | df | 2 |

| 0.001 | p | 3 |

| 0.078 | RMSEA | 4 |

| 0.96 | NFI | 5 |

| 0.96 | NNFI | 6 |

| 0.96 | CFI | 7 |

| 0.88 | RFI | 8 |

| 0.95 | GFI | 9 |

| 0.87 | AGFI | 10 |

Abbreviations: RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; NFI, normed fit index; NNFI, non-normed fit index; CFI, comparative fit index; RFI, relative fit index; GFI, goodness of fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index

The main assumption of the research is that the model fits the data, that is, to what extent a model is compatible with the data. Moreover, this fit shows the closeness of the variance-covariance matrix of the sample with the variance-covariance matrix of the population and is measured using different methods. In this study, the value of Chi-square in this analysis was 12.689, and the degree of freedom was 5, which resulted in 2.538 = χ2/df. Table 3 shows the direct and indirect effects of each of the variables.

| Direction | Effect | Significant |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional intelligence → victimization | -0.24 | 0.006 |

| Emotional intelligence → loneliness | -0.58 | 0.001 |

| Emotional intelligence → empathy | 0.53 | 0.001 |

| Loneliness → victimization | 0.41 | 0.001 |

| Empathy→ victimization | -0.19 | 0.008 |

| Emotional intelligence → loneliness→ victimization | -0.305 | 0.001 |

| Emotional intelligence → empathy→ victimization | -0.136 | 0.014 |

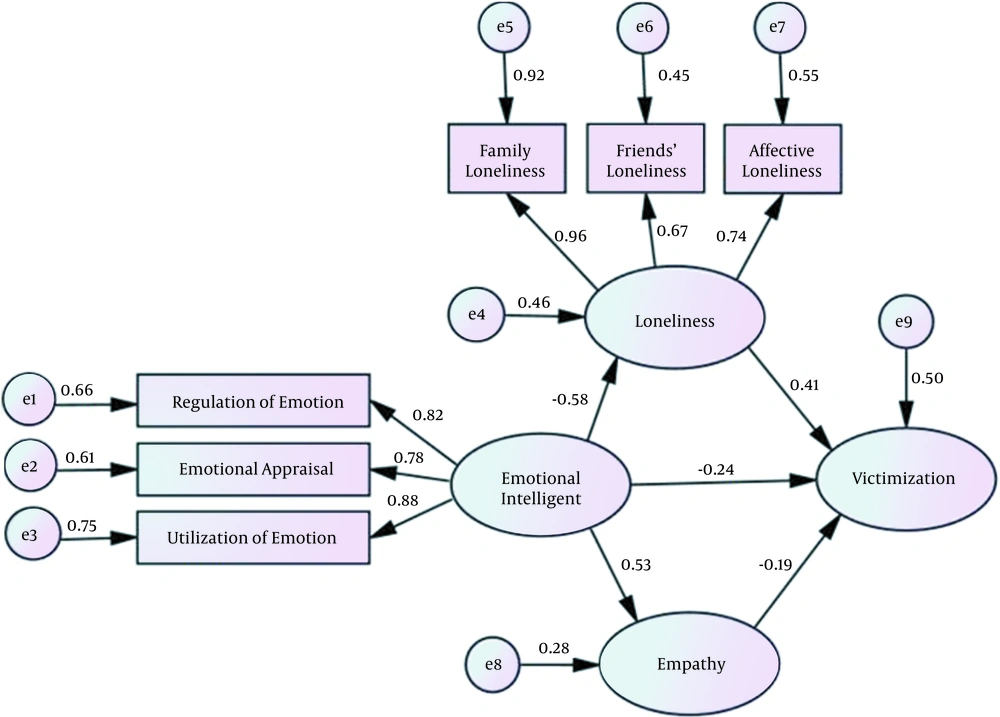

After examining and intervening with the variables of loneliness and empathy as mediating variables, the results of the model showed that EI had a significant effect directly on all three variables of loneliness, empathy, and victimization. The effect was positive for the empathy variable and negative for the variables of loneliness and victimization. The results also showed that feeling lonely had a positive, direct, and significant effect on adolescent victimization. In addition, empathy had a direct, negative, and significant effect on victimization. On the other hand, the results of indirect effects showed that EI had a negative, indirect, and significant effect on adolescent victimization through both variables of feeling lonely and empathy. After examining the direct and indirect effects of the structural model, Figure 2 depicts the final research model.

5. Discussion

Victimization at school is one of the problematic behaviors in adolescence that has recently attracted the attention of researchers and experts in the field of educational psychology. This topic has become the central theme of many studies in the past three decades (41). Pearson correlation results indicated that EI had a significant negative relationship with victimization. Similarly, the two components of EI (i.e., regulation of emotions and utilization of emotions) had a significant negative association with victimization. In addition, EI was found to be a negative predictor of victimization. This finding is consistent with the findings of previous studies (17, 19, 26, 27).

Students in schools are one of the most important groups who are exposed to bullying by others and are somehow victims of their violence. Sacrifice is a process that usually occurs frequently for three months or several times a week (42). Victims of some traits, such as weakness and shyness, seem to be introverted, emotional, insecure, and cautious and have high levels of anxiety (37). Victimization is also somewhat associated with student suicide and predicts numerous internal problems, such as loneliness and low self-esteem (25). Factors affecting victimization are complex and multiple. Some factors, such as parental performance, learning environment, emotional-social atmosphere prevailing in schools, and physical, behavioral, and socio-cognitive status of the individual, are among the items that have been studied in various studies (43).

Researchers believe that there is a negative and significant correlation between EI and adolescent victimization. This finding means that peer acceptance is associated with a better understanding of emotions, and EI is associated with problem-solving skills, which victims are deprived of because they sometimes behave inadequately in dangerous situations (34, 44). The research evidence shows that victims are deprived of the problem-solving and social skills that children with high EI have. In addition, victims are socially anxious, have a low social position, and have limited close friends, presenting that they have low degrees of perception and emotion regulation, in other words, low EI (45).

Consistent with the results of this study, Lomas et al. (46) showed that lower scores of the EI dimensions were significantly related to poor decision-making, low-level stress management, and control of emotions in victims. Also, poor EI dimensions predicts a tendency to victimization in adolescents. In another study consistent with the results of this study, the research evidence showed that adolescents who are victimized by their peers are less able to recognize emotions and understand the thoughts and ideas of others (31, 47). Therefore, it can be said that individuals with well-developed EI are generally more aware of their emotions and can manage and express those emotions effectively (48). In justifying this research finding, it can be said that when adolescent victims cannot recognize, understand, manage, and express their own or their peers’ emotions, they become victims of other individuals’ behaviors, and therefore low EI leads to adolescent victims.

On the other hand, the results showed that empathy had a negative and significant relationship with victimization. Researchers have demonstrated that victims have low scores on social cognition. Therefore, if victims are unable to understand, recognize, and regulate their emotions, they might be prone to rejection. As a result, rejected adolescents have limited friends and, therefore, fewer chances to understand and feel the cognitive status of others. Consequently, they doubtlessly find others aggressive and dishonest, which leads to socio-cognitive preconditions for showing empathy with peers (20). According to previous studies (49-51), empathy plays a principal function in adolescent victimization because empathetic behavior toward others eases the feature of interpersonal connections and, as a result, could prevent victimization and encourage adaptation in adolescents. Therefore, the negative effect of empathy on adolescent victimization can be expected. On the other hand, some researchers believe that constructive relationships with peers are based on empathy because emotional relationships with others construct a caring attitude. Emotional symptoms might also result from negative relationships with peers (e.g., victimization). In other words, it can be said that victims are prone to emotional problems, and victimization might play a role in subsequent emotional symptoms (52).

Researchers believe that adolescents who are socially anxious or lonely view their peer relationships negatively and therefore report higher levels of victimization. It can also be said that adolescents who were sacrificed in different ways reported more feelings of loneliness than adolescents who were sacrificed in only one form. In addition, good social relationships with peers and classmates reduce the relationship between loneliness and victimization. As a result, in justifying this finding, it can be said that adolescents who feel lonely might have a wrong view of social relationships due to repeated harassment, which leads to their victimization. Therefore, it can be said that positive relationships with others can provide a basis for correcting negative beliefs about oneself and others and reduce loneliness and consequently reduce or prevent victimization. On the other hand, the research evidence in line with the results of this study has shown that the victims are isolated and excluded individuals who lack social support. They are obedient in their relationships, thereby maximizing the likelihood of experiencing distressing symptoms. Therefore, social support for adolescents can help reduce their feelings of loneliness, which in turn makes the group less likely to be victims of others, and therefore loneliness can play a mediating role between victimization and negative peer experiences (38, 53, 54). In addition, consistent with the results of this study, Atik and Guneri (55) indicated that feelings of loneliness and isolation increase the likelihood of high school students becoming victims. Consequently, the short-term and long-term problems associated with loneliness will lead to student victimization.

The first limitation of the present study was that the results were obtained through questionnaires, and it is not clear to what extent the results pertain to actual behaviors in everyday life. Another limitation of this study was related to the spatial and temporal realm of the study. This study was conducted on students in Yasouj; therefore, the generalization of the results to other individuals or other cities should be made with caution. Since the current study was correlational, causative relations were not well established here. As a result, to obtain more precise results, it is suggested that these variables be studied through psychological experiments and interventions. Moreover, the researchers interested in this field are recommended to plan such studies in the future that explore the relationship of EI, empathy, bullying, victimization, and loneliness with different variables, such as self-esteem, parenting styles, attachment styles, and self-efficacy. In this way, comprehensive and reliable knowledge can be obtained about these variables and the relationships of these constructs with other constructs, which are more capable of relevant planning.

5.1. Conclusions

According to the prominent role of bullying and victimization in students’ mental and physical health, it is suggested that such programs as lectures and family training sessions be organized to increase coping skills and prevent bullying and victimization. These suggestions cannot be put into practice without the direct supervision and cooperation of parents, families, and professionals involved in education.