1. Background

Difficult life experiences in adulthood constitute a challenge to the self (1) and identity (2). Evidence reports that loss of self and identity results from chronic conditions such as traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) (1, 3). A disabling condition (such as TSCI) makes the injured person dependent on the caregiver and necessitates physical assistance from others (4). It enters the surrounding context through social actions and interactions (5, 6) and affects the entire family system (7-9). Various reasons forced the family members to take on the caregiver role (10).

Informal caregiving is a life-consuming and stressful activity, impacting the social, emotional, and financial aspects of the caregivers’ lives (11). It is a crisis that redefines roles, expectations, and routines for the family members. These changes are associated with alternations in their identity (11, 12). Here, the social aspects of the self of the individual with injury remain intact and are maintained by the actions of others (1). However, the caregiving tasks may gradually increase, control the informal caregiver’s life, and replace all previous activities and practices. Therefore, the caregivers’ selves may become engulfed by caregiving activities (13). The caregivers are the victim of events beyond their control. In response to the feeling of being a victim, the deepest layers of the personality are activated, and a return to childhood adaptation patterns is seen (14, 15). They may experience changes in identity and self as their roles change (13, 16-19). Thus, adaptation and reconstruction of the lost identity and self are necessary for them (14, 15). Fortunately, there are also pieces of evidence about self-transcendence and post-traumatic growth in informal caregivers of chronic conditions (16, 18, 20).

It has long been assumed that self-perception is a purely analytical concept related to philosophy (21). Philosophically, the self is the bedrock of human existence and the ground for self-knowledge, experiencing the world for us and rationally organizing it (22). To them, the self is a perfect, immortal, and true essence of a person who dwells in an imperfect and sinful body and returns to his pure nature at death. Traces of this idea can be seen later in the divine religions (23, 24). However, studying the self is not limited to philosophy (24). The psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and counselors who deal with the “psyche” are overtly and covertly dealing with the self as well (24, 25). Cultural theories often use self and subject interchangeably (22). The nature and development of the self have been a significant debate within psychoanalysis (24). To the pioneers of psychoanalysis, the self was an agent and a powerful, individualistic, free, and initiative subject who possesses conscious experiences (such as worldview, feelings, beliefs, and desires) and whose will prevails over others’ will. Moreover, gender influenced its dominance in human relationships (22, 25-28). However, the Enlightenment thinkers disagreed with them. To them, the subject was a toy directed toward the ideal state of being that he must become as per the expectations of power. It experiences a sense of isolation and vulnerability at the core of modern individuality (22, 25, 29). Then, intersubjectivity entered the scene, and the subject’s self extended beyond the “self” boundaries and focused on the “other.” This knowledge is necessary to understand human social behaviors. The contemporary psychoanalysts moved toward object relations theories (27, 30-32). To them, human beings cannot create a self for themselves; thus, the existence of an “other” and a sufficiently good enough environment are necessary to create and organize a self (31-35). Eventually, Kohut’s self-psychology theory introduced empathy and introspection to psychoanalysis. He proposed that we understand others not by observing their behavior but by empathizing with their mental state (32). Empathic capacity is a product of complex early child-caregiver interactions (36). We cannot overlook the significance of empathic ability in caregivers and the positive effects of empathy for caregivers and care receivers (37).

What has been said illustrates that people with TSCI and their informal caregivers are clinical populations that experience and report issues related to the self and identity (1, 17, 38-40). Moreover, self-defects and identity crisis are clinically significant issues for psychiatrists, psychologists, and rehabilitation counselors (40). On the other hand, the health policies are toward community care and community-based rehabilitation (41). This means implementing critical health policies in a human context, which are not ready to use self in caregiving. The crucial role of informal caregivers in empowering individuals with TSCI (42, 43) highlights the significance of using self to empathy, guiding and directing self-agency for goal setting, motivation, and emotional and behavioral regulation (44-46). Therefore, it is vital to explore informal caregivers’ self-perception as an interdisciplinary area of knowledge that requires intensive biopsychosocial attention. Unfortunately, we could not find studies on the self-perception of informal caregivers of individuals with TSCI. Therefore, in this paper, we tried to answer the question, how do the informal caregivers of individuals with TSCI perceive themselves? The results of this study may be effective in revising health policies and designing appropriate and timely psychological interventions regarding the caregivers’ need for self and identity reconstruction.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to explore self-perception from the viewpoints of informal caregivers of individuals with TSCI.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This qualitative research was conducted using the conventional content analysis method (47). The rationale behind choosing this research method goes back to the ambiguous nature of self (39). Choosing this qualitative method allowed us to explore the caregivers’ perceptions of themselves.

3.2. Sampling

The target sample population was informal caregivers of individuals with TSCI. We have selected the participants through purposive sampling (non-probability sampling in which the investigator selects the participant based on specific criteria) from those who volunteered to participate. The inclusion criteria were that the participants consider themselves as the primary caregiver of the injured person and that more than 6 months (48) have passed since the beginning of the caregiver role. The exclusion criterion was the lack of enough cooperation in interviews. We performed purposive sampling under the principle of maximum variation until we reached data saturation. Therefore, informal male and female caregivers participated in the study in the roles of father, mother, spouse, children, and siblings.

3.3. The Participants

Twelve adults participated in this study. Participants included 7 informal female and 5 informal male caregivers. The participants’ age range was from 19 to 71 years. There were comparative groups between participants, including men/women, parents/spouses, literate and employed men/women, illiterate and unemployed men/women, and married/unmarried girls and boys. Table 1 displays the participants’ demographic information.

| Identification Code | Gender | Age | Marital Status | Level of Education | Job | Kinship Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Female | 42 | Married | Elementary | Stay-at-home spouse | Spouse |

| P2 | Female | 66 | Married | Literacy campaign | Self-employed | Spouse |

| P3 | Female | 51 | Married | Diploma | Stay-at-home spouse | Mother |

| P4 | Female | 71 | Married | Illiterate | Stay-at-home spouse | Mother |

| P5 | Male | 37 | Single | Diploma | Stay-at-home spouse | Brother |

| P6 | Female | 38 | Married | MA | Civil servant | Spouse |

| P7 | Male | 31 | Married | BA | Self-employed | Spouse |

| P8 | Female | 40 | Married | Illiterate | Stay-at-home spouse | Spouse |

| P9 | Male | 40 | Married | PhD | Civil servant | Brother |

| P10 | Female | 19 | Married | Diploma | Stay-at-home spouse | Spouse |

| P11 | Male | 30 | Married | Associate degree | Self-employed | Offspring |

| P12 | Male | 55 | Married | Diploma | Self-employed | Father |

3.4. The Research Setting

We coordinated the place and time of the interviews with the participants and conducted the interviews in a place where the participants felt more comfortable participating in interviews. We visited them at governmental and nongovernmental outpatient clinics for TSCI or at the participants’ homes. Each person participated in a maximum of 4 interviews. The first and the second interviews were face-to-face interviews. The selected people participated in individual interviews at outpatient clinics providing rehabilitation services to individuals with TSCI or their private homes. We conducted the third and fourth interviews by telephone if we needed more details about the quotes.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

We submitted the study to the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for ethical approval as a PhD dissertation in Rehabilitation Counseling (code: IR.USWR.REC.1396.209). We contacted the selected individuals to give them the initial information about the project. They participated in the interviews voluntarily. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to their participation in this study. All participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage, and they were ensured about the confidentiality of their data. On the participant information sheets, the first author provided her phone number, the needed contact numbers of the institute responsible for implementing the project, and the needed contact numbers of the relevant organizations offering counseling services and support in the case of psychological distress caused by the study.

3.6. Trustworthiness

To ensure data accuracy and trustworthiness in this study, we checked credibility, confirmability, transferability, and dependability criteria. To ensure credibility, we had a long-term involvement with data. We used constant comparison methods until we reached data saturation. For confirmability, the research team members reviewed the data, codes, and categories to exchange views (peer check). The researchers summarized the results and gave them to the participants to receive feedback on the results (member check). Furthermore, 4 experts checked the data, analysis process, and results through an audit trail (expert check). Moreover, we tried to follow the principle of sampling with maximum variation and increase the number of conducted interviews to ensure transferability. A complete description of the research process, including data collection, analysis, and formation of the codes, was documented step by step to provide the possibility of research follow-up by the audience and readers and ensure dependability (49, 50).

3.7. Data Collection

We collected data from 2018 to 2022. We performed in-depth semi-structured interviews and used field notes. Each interview lasted 60 - 90 minutes. The interview schedule consisted of broad, open-ended questions that facilitated in-depth exploration of the perception of the self. We asked the participants, “who were they, and what did they think about themselves?” Also, we asked them whether “caring for a person with TSCI affected their perception of themselves. Moreover, if so, what was the impact?” As the research progressed, the questions changed gradually to suit the needs to complement the dimensions and properties of the categories, as well as based on the participants’ answers and feedback. Data collection and data analysis were performed simultaneously in this study. The data collection and analysis processes ended with reaching saturation.

The research team consisted of the first author as a PhD candidate student supervised by 6 expert faculty members. An expert faculty member conducted an interview. The first author conducted the rest of the interviews. She recorded the interviews, listened to them, transcribed them verbatim, and took the lead role in analyzing the data under the research team’s supervision.

3.8. Data Analysis

We used the conventional content analysis and constant comparison method to analyze the data, and we were committed to following the rules of inductive qualitative content analysis to analyze the data (51). The researchers divided the data into manageable meaning units such as words, sentences, phrases, and paragraphs and then labeled each of them as codes. We constantly compared the codes and grouped them based on similarities and differences to form the main category and subcategories (51).

4. Results

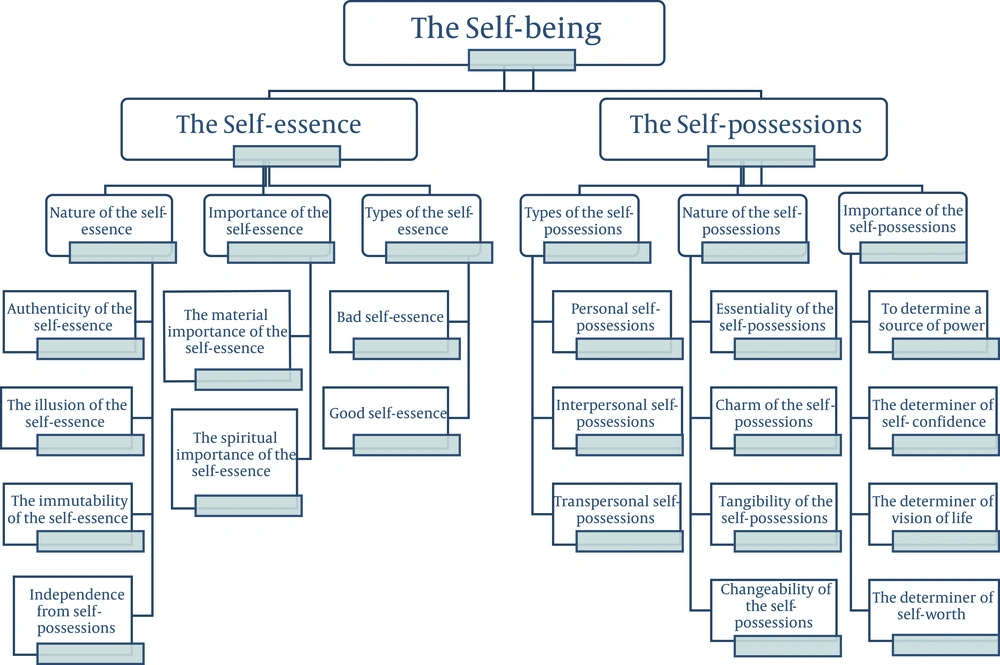

The study’s findings based on participants’ quotes were the main category (the self-being), 2 higher-level subcategories (self-essence and self-possessions), and 6 second-level subcategories (the nature of self-essence, the significance of self-essence, types of self-essence, types of self-possessions, the nature of self-possessions, and the significance of self-possessions). Moreover, 19 first-level subcategories related to them. The main findings, including category and subcategories, are summarized in Figure 1.

4.1. The Self-being

The “self-being” is the main category that emerged in this study as an in vivo code. A participant’s quotes indicated that he attributed his being to his self-essence, not to what he had or did not have as self-possessions. It is crucial to remember that the participants were Iranian adults with internalized values and beliefs. Therefore, the social, cultural, and educational teachings of Iranian society may affect their self-perception. “Self-essence” and “self-possessions” are in vivo codes as well; we used them as higher-level subcategories for the “self-being” main category.

4.1.1. Self-essence

This part of the study contains metaphysical and subjective material that is intangible, complex, incomprehensible, and non-experiential. However, some quotes spoke of an authentic, valuable, and unchangeable component of self called “my essence.” They attributed who they were to “self-essence.” “The nature of self-essence,” “the significance of self-essence,” and “the types of self-essence” are lower-level subcategories for self-essence.

4.1.1.1. The Nature of Self-essence

The participants pointed out the nature of self-essence and its characteristics, distinguishing it from the nature of self-possessions. “Authenticity,” “illusion,” “immutability,” and “independence from possessions” are subcategories of the nature of self-essence.

4.1.1.1.1. Authenticity of Self-essence

To the participants, self-essence is naturally authentic, original, and balanced because God gave it equally to all human beings to live in balance. It helped them to feel they were normal and on the right path and decreased guilt. A participant said:

My essence is authentic and original because it is natural and balanced (emphasis). God has given it to us to live in balance. In my nature, everything is normal. Authenticity is a pure thing that emanates from within human beings to show right and wrong to them (emphasis).

4.1.1.1.2. The Illusion of Self-essence

To the participants, self-essence is naturally illusional compared to self-possession. The illusion of self-essence is an advantage because no human being can own or manipulate it for his benefit. This helped them to consider themselves equal to others, although they were different in self-possession. A participant said:

My self-essence is invisible, and it is not touchable (emphasis). It is somehow mystical and illusional to be out of reach of humans so that they cannot manipulate it for their benefit (emphasis), so no more injustice! Because all of us are equal (emphasis).

4.1.1.1.3. The Immutability of Self-essence

To the participants, self-essence is naturally immutable in contrast to mutable self-possessions. This ensures that self-essence is not defective or lacking. Therefore, humanity and dignity are preserved under any circumstances. This ensures self-continuity in times of defect or lack of self-possessions. A participant said:

My essence does not change with changing circumstances! (emphasis). Let me give you an example: This tree is a willow tree; suppose it is winter, the leaves of this tree fall, or we take an ax and cut the trunk, or we burn it! This tree has indeed changed, but only its appearance has changed; the nature of this tree has not changed! Whatever disaster befalls this tree, the willow tree cannot become a palm tree! (emphasis). This is true about me too! No matter how much I would change under different circumstances; in the end, I am still a human being! Moreover, I would not transform into another creature like a cow! (laughter).

4.1.1.1.4. Independence from Self-possessions

To the participants, self-essence is naturally independent of self-possession. Self-possessions can derive their credibility from self-essence. However, the credibility of self-essence does not depend on self-possessions. It ensures self-worth for the participants. A participant said:

You must separate my self-essence from my possessions (emphasis) because if my possessions could determine my value, then my dignity is severely in question! (emphasis). Till I have money, wealth, health, and power, I am worthy! However, if I lose them one day or a breakdown happens to them, I will become worthless totally! (emphasis). My essence is the principle, and the possessions are the sub-principles. I came to this world with human dignity, and I will leave it with the same human dignity regardless of what I have or I do not have! (emphasis).

4.1.1.2. The Significance of Self-essence

The existence of self-essence is essential because it is a neutral comparison reference that affects the life and the afterlife. Therefore, the material and the spiritual significance of the essence of the self are considered basic concepts for the importance of self-essence.

4.1.1.2.1. The Material Significance of Self-essence

To the participants, self-essence has material significance. A participant who considered self-essence a neutral comparison reference that had materialistic and worldly significance said:

The material significance of self-essence becomes clear when we consider it as a neutral frame of reference, which as human beings, we all have an equal share of it, and we are all unable to manipulate it! (emphasis). So, it can reduce comparison, judgment, domination, greed, discrimination, and oppression! (emphasis). In this way, we stop exploiting each other and even other beings because we understand that we are all equal! (emphasis).

4.1.1.2.2. The Spiritual Significance of Self-essence

To the participants, self-essence has spiritual significance. Self-essence can extend human existence to before and the afterlife. The essence of self motivates the sense of belonging and being under the protection of a subjective authority figure. A participant said:

When I said that my essence was created and given to me! This way of thinking has 2 aspects. The first is that I am a creature, and the second is that I have a creator! Moreover, this creator said: you belong to me, and you will return to me! (emphasis). It creates a good reputation for me, and it also defines a hopeful future for me! Even for the afterlife! Furthermore, it puts me under the protection of a more powerful being than myself who sees what is happening to me every moment! (sighs). To me, this is important! (emphasis). Why? Because it creates balance for me! (emphasis).

4.1.1.3. Types of Self-essence

To the participants, self-essence can be bad or good. On the one hand, a belief about bad self-essence in self and others leads to disappointment in self and others; on the other hand, a belief about good self-essence in self and others gives hope to self and others. Bad self-essence and good self-essence are 2 basic concepts of self-essence types.

4.1.1.3.1. Bad Self-essence

To some participants, self-essence can be bad, and this evil nature is unchangeable. Accordingly, one may perceive the self and others as a threat or an enemy. A participant said, “some people have a bad nature, so no one is safe from them! (emphasis). A person with a bad essence never changes and does not get better!”

4.1.1.3.2. Good Self-essence

To some participants, self-essence is good, and there is no such thing as an evil nature. The essence of all human beings is good, but their conditions are different. Accordingly, one may perceive the self and others as an opportunity or a friend. A participant said:

The essence of all human beings is good because it attributes to the essence of God! (emphasis). Self-essence is like a diamond! God gave it to all of us, but one keeps the diamond in a box, one hangs it around his neck, one puts it on the shelf, one’s diamond falls on the ground, one’s falls into the cement, and one’s falls into the sewer! (emphasis). A diamond is a diamond, even if it sinks in sewage! It does not turn into sewage itself! (emphasis).

4.1.2. Self-possessions

“Self-possessions” is the second subcategory related to self-being. This part of the study contains objective and tangible material that is meaningful, understandable, and experiential for most participants. Most participants easily talked about what they had and did not have. They attributed who they were or were not to what they had or did not have. “Types of self-possessions,” “nature of self-possessions,” and “significance of self-possessions” are lower-level subcategories of self-possessions.

4.1.2.1. Types of Self-possessions

According to the participants, self-possessions included personal, interpersonal, and transpersonal possessions attributed to the personal, interpersonal, and transpersonal aspects of self.

4.1.2.1.1. Personal Self-possessions

According to the participants, personal self-possessions include name and lineage, physical health, beauty, youth, physical strength, gender, instinct, intelligence, talents and skills, intellect and logic, heart and emotions, personality, conscience, self-confidence, self-agency, self-efficacy, money, savings and financial infrastructure, individual identity, individual roles, social status, employment, education, income, fame, and power. Personal possessions help the individual to be an independent being. The quantity and quality of participants’ personal self-possessions were recognized, compared, judged, and labeled by self and others. Therefore, self-worth, self-confidence, and self-being were rooted in personal self-possessions. Moreover, the superiority or inferiority of personal self-possessions made the participants feel superior and inferior. A participant said, “I am nothing because I do not have a house or a car, I do not have jewelry, and I am not a beautiful woman! (pause). All I have is this torn dress! I am miserable! (emphasis).”

4.1.2.1.2. Interpersonal Self-possessions

Interpersonal self-possessions are referred to as interpersonal dimensions of self. Here, the individuals perceived themselves as a part of a whole that is not independent of others. The narratives showed that people with TSCI and their caregivers considered each other’s possessions. They belonged to each other and experienced a sense of ownership, being in debt, guilt, empathy, love, attachment, responsibility, and dependence on each other. They were committed to each other in the past, present, and future and shared their resources. They had commonalities such as a shared territory, shared children, shared experiences, shared memories, shared problems, and a shared future. People with TSCI and their caregivers played essential roles in each other’s memories, recent experiences, and future goals. They owed, interested, or needed each other. The more the caregivers depended on the injured person and their interpersonal possessions, the more profound the effect of the occurrence on the caregivers’ selves. A participant said:

This is my husband, and these are my children! These are mine! They belong to me! (emphasis). They are not separate from me! (emphasis)! My children are my jewelry! (pride). … I devoted myself to taking care of them! (emphasis).

4.1.2.1.3. Transpersonal Self-possessions

“Transpersonal self-possessions” have a subjective and non-objective nature and include mental images, myths, memories, spirituality, God, the universe, faith, conscience, and religion. From the participants’ viewpoints, especially those who were frustrated with themselves and others, transpersonal self-possessions were in a position of power. They potentially compensated for the lack or deficiencies in personal and interpersonal self-possessions. A participant said:

No one cares about me! God is everyone to me! (emphasis). My parents and my husband’s parents have died, and TSCI happened to my husband; my son is still a child, and my brothers are busy with their own lives! (emphasis). There is just God for me, and that is enough for me! (pride).

4.1.2.2. The Nature of the Self-possessions

The participants attributed characteristics such as essentiality, charm, tangibility, and changeability to the nature of their possessions.

4.1.2.2.1. Essentiality of Self-possessions

To the participants, self-possessions are naturally essential because they guarantee survival. They serve as a source of problem-solving resources for the individual to meet their needs. A participant said:

Money is essential to meet needs! We, as human beings, need water, food, and shelter to survive! (emphasis). We need money to meet any other needs! (emphasis). For the money itself, I either must work or have someone to support me! (emphasis). I need literacy or skill to have a job! See, it is like a chain! All of them are necessary to survive! (emphasis).

4.1.2.2.2. Charm of Self-possessions

To the participants, self-possessions are naturally seductive because they make people focus on them, so they forget the passage of time and other aspects of their existence. Therefore, eventually, it makes people’s lives 1-dimensional. A participant said:

It is as if I have been metamorphosed (sigh). I do not have anything more valuable than my family. I dedicated myself to caring for my family (emphasis). I have not noticed the passage of time at all. However, now I am surprised to see the older woman in the mirror that is me! (emphasis). She tells me that she did not live a life for herself at all! (sigh).

4.1.2.2.3. Tangibility of Self-possessions

To the participants, self-possessions are naturally tangible. Therefore, it is more comprehensible than self-essence. Nevertheless, since they can be seen, they are compared with other people’s possessions. People are valued based on the quantity and quality of their possessions; based on that, some people are recognized as superior and others as inferior. A participant said, “I cannot hide what I have and what I do not have! These are obvious to other people and me! People see me. I cannot hide my weakness! Poverty and misfortune cannot be hidden. People watch and judge (sorry).”

4.1.2.2.4. Changeability of Self-possessions

Most of the participants were surprised by the occurrence of TSCI. They did not even imagine that the conditions would change so that they lose their valuable possessions or cause severe defects to them. This issue becomes vital when people forget the changeability of possessions and safely depend on self-possessions that may change at any moment. Along with them, their social status, self-esteem, sense of self-worth, and dignity will also change. A participant said:

We were surprised! We never thought this would happen to us. My husband was our breadwinner, and we all depended on him! We relied on him safely. We counted on his income. However, once it happened, it messed up all our lives (sorry).

4.1.2.3. Significance of Self-possessions

From the viewpoints of the participants, the significance of self-possessions is to function as a determiner of “self-worth,” “the vision of life,” “self-confidence,” and “be a source of power.”

4.1.2.3.1. The Determiner of Self-worth

According to the nature of self-possessions, including being needed, meaningful, attractive, concrete, and changeable, self-possessions can influence individual and collective values, becoming an ideal of hopes and dreams and a criterion for self-evaluation by self and others. A participant said, “who I am and what my worth is has a lot to do with what I have and what I do not have! I am nothing without money! (emphasis).”

4.1.2.3.2. The Determiner of the Vision of Life

Valuable self-possessions could determine one’s life perspective, goals, and future direction. The development of individual, interpersonal, and transpersonal dimensions of oneself is one of the consequences of determining the vision of life. A participant said, “I have a clear purpose and path in life! (emphasis). That is caring for my loved ones till I live! (determined). I define every purpose with this in mind.”

4.1.2.3.3. The Determiner of Self-confidence

Self-possessions have been mentioned as a source of self-confidence by the participants in this study. By stimulating mechanisms such as social comparison, judgment, valuation, and feedback, self-possessions can induce superiority or inferiority, create pride or shame, and be considered as a source of feeding self-confidence or a factor of destroying it. A participant said:

I was not a vital person in the family before this incident! (emphasis). However, TSCI happened to my brother (sorry). I take care of him! He cannot survive without me now! (pride). He needs me! Once my brother’s wife said, “she wished his son would become someone like me! (happy).” Now I am proud of myself because of the key role I play in their life! (pride).

4.1.2.3.4. To Determine a Source of Power

The participants recognized their possessions as a source of power. Self-possessions were considered a criterion of superiority and increased the feeling of efficiency, problem-solving ability, self-confidence, and authority. Lack or a defect in self-possessions puts a person in a vulnerable position that requires help from others. A participant said:

“I think! A woman must go to school because she needs knowledge, and she must have a job too. Moreover, she must earn a living for herself because they create power and give her freedom of action! (emphasis). If women are weak and dependent on men to survive, men will crush their personalities for a piece of bread! (emphasis).”

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore self-perception from the viewpoints of informal caregivers of individuals with TSCI. The findings of this study include a main category labeled as “the self-being.” “Self-essence” and “self-possessions” were 2 higher-level subcategories related to the main category, and there were 25 lower-level subcategories related to the higher-level subcategories.

The self is a complex concept studied in psychological sciences and philosophy; thus, it is difficult to separate the realms of philosophy and psychology regarding the self. We should note that the selected participants were adults who lived in Iranian society and were brought up under the influence of the teachings of Iranian culture, tradition, and religion and the changes these teachings underwent over time. They have been exposed to traditional, modern, religious, and nonreligious ready-made meanings for years, and they have internalized beliefs that have influenced their perception of themselves. Therefore, it is not surprising if the participants, as ordinary adults, perceive themselves in a format that resembles deep philosophical or theosophical concepts in general and psychological concepts in detail.

This article is a part of the findings of a broader qualitative study entitled: “Explanation of self-reorganization process in informal caregivers of people with TSCI,” which was designed to explain the process of self-reorganization. We realized that we would not be able to explain the process of self-organization without a framework of caregivers’ self-perception. This is because, according to the nature of qualitative research, we had to abandon our presuppositions and were not allowed to use existing theories to guide the research. Therefore, we have tried to refer to the participants’ quotes and wait for a structure to emerge for the self that the participants used as a frame of reference to perceive themselves. “The self-being,” which is mentioned in this study as the main category, is a framework resulting from the study itself, by which the informal Iranian caregivers of individuals with TSCI that participate in our research perceived themselves. The uniqueness of these interdisciplinary findings is in their being local and based on Iranian culture. In addition, this structure can discuss debates such as subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and spirituality in the framework of what these informal caregivers understand about their being.

“The self-being” and its 2 higher-level subcategories (“self-essence” and “self-possessions”) are abstract concepts that emerged in this study as in vivo codes. This is consistent with the viewpoints of pioneers of philosophy and divine religions (23, 24). “The self-being” in this study has a metaphysical dimension called “self-essence,” which is consistent with philosophical and religious beliefs (23, 24); however, it is not consistent with psychoanalysis and neuroscience evidence that consider a difference between phenomenology and metaphysics. Moreover, they distinguish between experience and reality (31, 52). Nevertheless, the lower-level subcategories of this subcategory showed that the metaphysical state of self-essence was valuable and functional for the participants in this study. It can create imagination and cognitive understanding capacity that goes beyond phenomena and logic. Self-essence functioned as a neutral and universal frame of reference that was not influenced by self-possessions, and it had an inherent dignity that was preserved under any circumstances. In a demanding situation, the informal caregivers attributed their self-being to their essence of self to endure hardships and maintain their sense of self-worth and self-confidence despite the loss or damage of their meaningful self-possessions. It gives them the feeling of belonging to a power greater than themselves and extends their scope of being to pre- and post-personal existence. However, unfortunately, the fact is that the metaphysical view of the Platonic philosophy of self has been abandoned by most contemporary philosophers and most of the researchers that empirically investigate the development, structure, function, and pathology of the self (31, 52).

However, self-being had another dimension, including self-possessions that were needed, valued, empirical, and objective. Therefore, their quantity and quality are essential and are not equal or fixed, contrary to the nature of the self. These self-possessions contained the pain of loss and the joy of gaining simultaneously. They activate mechanisms such as social comparison and social feedback, label people as superior or inferior, categorize them, and create inequality. Self-possessions set life vision, determined self-worth, and self-confidence; it induces a feeling of shame and self-deprecation or pride and self-conceit in a way that the participants perceive themselves to be nothing or everything based on the quality and the quantity of their self-possessions. These findings are consistent with studies on caregivers of chronic conditions and their sense of discrimination (53), marginalization (54), self-conceit (55), vulnerability (56), isolation, loss of identity, and role changes (10). This is in line with the thoughts of Foucault and Enlightenment thinkers (28) in the sense of the presence of vulnerability and isolation at the center of the modern individuality of the subject (28, 29).

In our study, self-possessions include personal, interpersonal, and transpersonal self-possessions. These possessions were consistent with the dimensions of the self in Reed’s self-transcendence theory (18). In this study, the personal self-possessions included the possessions that belonged to the subject as a person. This is consistent with Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis. To them, the self is an agent and powerful, individualistic, free, and initiative subject who possesses conscious experiences such as worldview, feelings, beliefs, and desires, whose will prevails over others’ will. Moreover, gender influences its dominance in human relationships (21, 22, 25-28). However, there are lines of evidence that the majority of informal caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury were females (57), and they have lost their individuality, which is essential for their wellbeing (58).

Interpersonal self-possessions included the possessions that belonged to the subject as a part of a greater concrete whole. Injured people and their informal caregivers were among each other’s valuable possessions. They were interdependent. They had a shared past, present, and future. However, they had a sense of empathy, responsibility, indebtedness to each other, zeal, and attachment. These findings are consistent with most of the findings that focus on the experience of caregivers (8-10).

Transpersonal self-possessions in this study included the possessions that belonged to the subject as a part of a greater abstract whole. In a situation where personal and interpersonal self-possessions are lacking, the participants maintain themselves by relying on transpersonal self-possessions. Spiritual growth, transpersonal growth, and post-traumatic growth are positive consequences that are in line with the findings of this study (17, 20, 58).

5.1. Limitations

The abstraction of the concept of self was the most significant limitation faced. It was by purposive sampling and noticing the principle of maximum variation that we obtained essential data about the self. In addition, for the same reason, scientific research on the self was not sufficiently available. Another limitation we faced was the predominance of collectivist and religious cultures in the study context. The complexity of the concept of self and the qualitative nature of this research make the findings of this research not generalizable. Furthermore, we recommend that a 1-dimensional study of the self is insufficient, and it is more appropriate to study the self in the form of interdisciplinary research.

5.2. Conclusions

Informal caregivers of individuals with TSCI are the clinical community that needs specialized attention and proper psychological interventions regarding the self and identity. Participants’ perception of themselves is influenced by the lessons they have learned from self-experiences and their worldviews. Those participants who attributed their self-being to the existence of a fixed and universal self-essence, which was independent of variable possessions, maintained their sense of self-worth despite life’s difficulties. Such a self-perception leads to a culture of equality that tolerates individual differences, respects human rights, and avoids discrimination against each other. However, strong dependence on self-possessions makes the self-perception dependent and vulnerable to the quantity and quality of the self-possessions, and it leads one’s life to a 1-dimensional and vulnerable life that the participants’ self-worth and self-confidence change as the self-possessions increase or decrease.