1. Context

Menopause is defined as having occurred a year after menstrual bleeding has ended (1-3). It is a natural developmental transition that all women experience between the age of 49 - 58 (3, 4). During menopause, women may experience a range of biological, psychological, and social changes (3, 5-7), which have a significant effect on their quality of life (7-10). Psychological symptoms of the menopause include mood swings, sadness, depression, frustration, lack of motivation or interest, diminished energy, hopelessness, difficulty concentrating, difficulty making decisions, irritability, intolerance, nervousness, anxiety, and low self-esteem (1, 2, 5, 11-13). Among these symptoms, the most common psychiatric disorder is depression, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality consequences such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, chest pain, obesity, impaired interpersonal relationship, social and occupational dysfunction, and sexual health (2, 13-16). Studies of Iran have reported a prevalence rate of depression ranging from 4% - 64% among the Iranian population (17-20) compared to an estimated prevalence of 16.3% to 20% for the population worldwide (2, 11). The association between the menopausal transition and an increased risk of depression is an important, unspecified public health problem that requires much attention (14, 21). In this regard, both community-based cohort and cross-sectional studies have shown that menopause is a window of vulnerability to depression and psychiatric disorders (2, 22-29). The exact etiology of this relationship is not determined; however, various studies have assessed the possible causes of depression (1, 2, 11). Several studies report that biological, social, and psychological factors have a significant impact on the onset of depression during the menopausal stages (3, 30-33). Although there are some review articles regarding depression in menopausal women all over the world, there is no review article in this background in Iran (13, 27, 34). In addition, given the importance of mental health in the menopausal transition and the adverse long-term effects of depression on various aspects of women’s lives, this study aimed to determine the bio psychosocial issues leading to depression in the menopausal transition.

2. Evidence Acquisition

In this review, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was used as a guideline. This comprehensive literature review was conducted in three steps (35):

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

This study aims to answer the following research question: “What are the bio psychosocial risk factors of depression in the menopausal transition?”

2.2. Search Strategies for Identifying and Selecting Related Studies

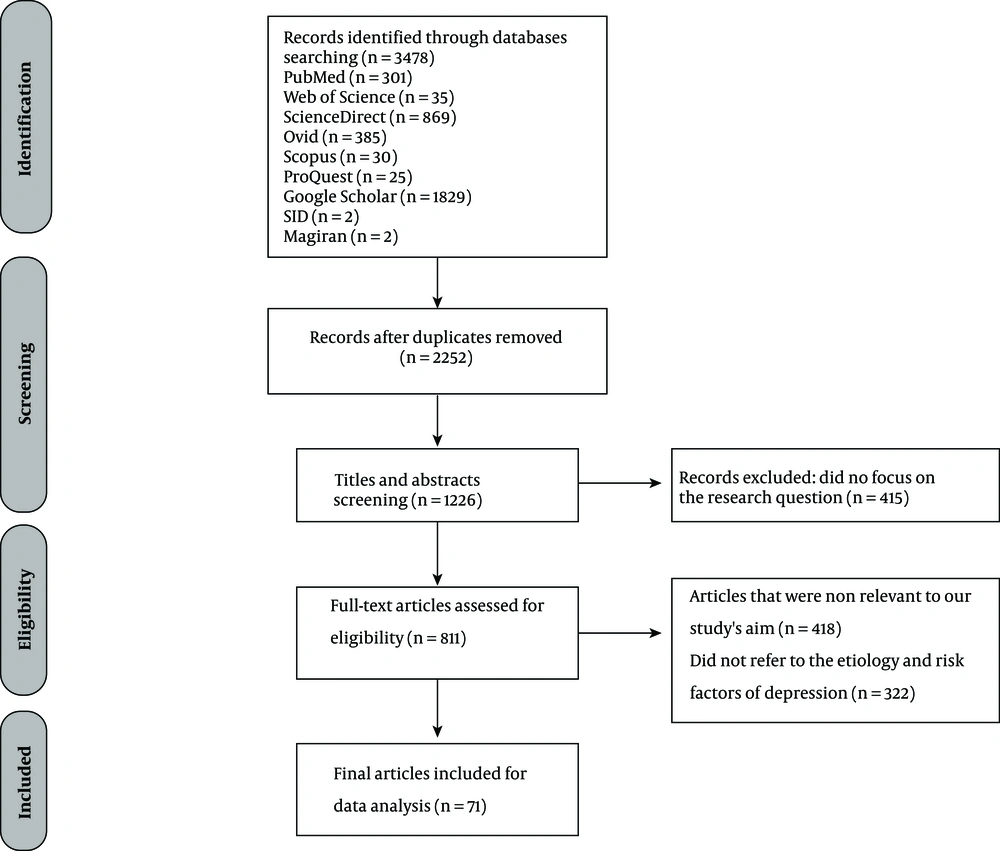

To address the research question, three researchers (FE, MA and EF) commenced the initial search independently using Google Scholar, Magiran, SID, PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Ovid, Science Direct, and ProQuest during November 2016 and April 2017. The researchers used Text Word and the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) with the keywords “psychological” OR “depression” OR “anxiety” OR “mood disorder” OR “psychiatric disorder” AND “femininity” OR “reproductive loss” OR “empty nest syndrome” OR “social issues” OR “psychosocial problems” OR “vasomotor symptoms” OR “hormonal changes” OR “biological” OR “menopausal symptoms” AND “menopause” OR “perimenopause” OR “midlife” OR “menopausal transition.” After the initial search, 3 478 related articles published between 1978 and 2017 were extracted. After discarding duplicate articles (n = 2 252), the remaining papers were screened in two stages. In the first stage, the titles and abstracts of all remaining papers were independently reviewed by three researchers (FE, MA, and EF) and those that met the entry requirements and answered the research questions were selected. The inclusion criteria were articles focusing on depression in menopausal-aged women that were published in scientific journals, and English and Farsi languages articles conducted in menopausal aged women. In contrast, studies that do not refer to risk factors of depression or clinical trials were excluded from this study. At the first stage of screening, 415 papers were discarded from the study. In the second stage of screening, the full texts of all remaining papers were reviewed and those who, despite referring to depression, did not refer to the etiology and risk factors of depression (n = 322) and were not related to the aim of the study (n = 418) were discarded from further analysis. In addition, the reference lists of the selected papers were checked to find more papers and conduct the search with a higher sensitivity and precision. In the end, 71 papers were used for the current review study (Figure 1).

2.3. Summarizing, Extracting, and Reporting the Data

Using the studies selected from the previous stage, the researchers carefully studied all the relevant papers and extracted and organized the information they needed for the current study. The content on the risk factors of depression in the menopause were organized into categories (Table 1). This project was found to be in accordance to the ethical principles and the ethical code of this project (IR.MAZUMS.REC.1397.012) was determined by Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

3. Results

In Table 1 the risk factors of depression in menopausal aged women are shown. The bio psychosocial risk factors of depression were divided into three major categories: biological, psychological, and social risk factors.

3.1. Biological

Several studies claim that biological factors play a role in the onset of depression in the menopausal period (10, 28, 34, 36, 37). The biological risk factors of depression include decreased reproductive hormonal level changes (10, 26, 28, 34, 38, 39), a long premenopausal period (more than 27 months) (31, 40, 41), severe menopausal symptoms including long-term vasomotor symptoms (i.e., hot flashes and night sweats) (1, 10, 25, 26, 31, 40), type of menopause (surgical vs. natural menopause) (10, 26, 28), premature menopause (29, 41, 42), decreased physical health, chronic medical diseases (13, 21, 26, 40, 43-46), use of antidepressants (28, 42, 47-49), and history of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) (5, 21, 31, 39, 47). While some studies have demonstrated a strong association between the presence of vasomotor symptoms and depression (10, 12, 21, 38, 47), others indicated depression as an indirect outcome of sleep disruption that occurs when experiencing hot flashes or night sweats (5, 21, 50). Problematic hot flashes were significantly associated with tiredness, social isolation, embarrassment, diminished self-esteem, loss of control, panic, dizziness, and depression (27, 31, 47, 50).

Type, stages, and time of menopause are other factors that affect the occurrence of depression in the menopausal transition (28, 51). Women who have undergone a surgical menopause are more likely to experience depression (10, 14, 26, 52). Additionally, women who experience a premature menopause are more likely to experience depression compared with the general population (26, 41, 53). Large community-based cohort studies showed that the menopausal transition is a window of vulnerability to depressive disorders, and it is considered an independent biological basis in the onset of depression (29, 54). The results of some studies indicate that the prevalence of depression in premenopausal women is approximately twice that in premenopausal women (10, 23, 27).

An important biological risk factor relating to depression is the hormonal level changes in this period (10, 23, 26). Estrogen deficiency might increase the susceptibility for depression (36): two hypotheses might explain the link between the development of depression and hormonal changes in estrogen. First, low levels of estrogen associated with a depressed mood and second, unstable and irregular patterns of hormone production during menopause increase the vulnerability to depression in susceptible women (14). A study showed that a greater variation in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol hormones was significantly associated with depressive symptoms in the menopause transition (38, 48). Estrogen therapy, during the premenopausal or postmenopausal periods, can diminish mood disorders and enhance the subjective sense of well being (34, 36).

A history of PMS is another predictor of depression during the menopausal transition (25). Previous studies have indicated that both disorders (PMS and depression) are caused by underlying hormonal changes and changes involving the central nervous system (21, 25, 27, 55).

3.2. Psychological

Although no specific psychiatric disorders are associated with the menopausal transition, psychological issues that were experienced during the menopausal period were found to be a main predictor of depression (9). As a history of depression is the strongest predictor of depression (1, 13, 21, 25, 31, 41, 47, 55), women with a history of depression are more vulnerable to the onset of depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition compared with those with no history of psychiatric disorders during their lifetime (16, 41, 52).

Other possible psychological problems that promote the occurrence of depression include a negative attitude toward menopause and aging (1, 5, 8, 16, 25, 26, 43, 56), a history of anxiety (9, 13, 15, 16), history of mood disorders (31, 34, 38, 57), family history of psychiatric disorders (46, 55), history of postpartum depression or postpartum blues (13, 25), a sense of loss in life such as a loss of control to their menopausal symptoms (1, 41, 49), loss of femininity such as unattractiveness (5, 8, 16, 25, 39, 49, 58), the loss of reproductive capacity (4-6, 12), low self-concept and self-esteem (1, 2, 5, 50), daily stressors (8, 13, 21, 26, 40, 44), and dissatisfaction with relationships (26, 43).

According to psychoanalytical perspective, menopause is defined as a time of disappointment and psychiatric vulnerability (28). While the psychosocial perspective considers the menopausal transition a natural part of a woman’s life that can lead to personal development with new knowledge and experience, for some women with severe menopausal symptoms, psychosocial perspective might lead to a conflict and loss of self-esteem (3).

An individual’s perceptions, thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs regarding the menopause have a significant influence on their experience of depression and other psychiatric disorders in this stage of their life (47, 59). Women with a negative attitude toward menopause are most likely to experience severe negative moods and psychological distress (5). For example, for many pessimistic women, menopause is a symbol of aging as well as becoming old and has a negative effect on the meaning of life for them (60). These women develop a feeling of lacking something; they believe that the menstrual cycle is a sign of youth and power, and the loss of this event creates high levels of stress and mood swings in the menopausal transition (6, 8). By contrast, for optimistic women, menopause is a time of pleasure and relief from menstruation bleeding and fear of pregnancy, and a time of doing their favorite activities (41). Menopausal symptoms such as vaginal dryness, memory problems, health complaints, and life stress are significantly related with negative attitudes toward the menopause and predisposed depression in this period (21). Women’s self-concept might change during the menopausal transition. Studies have shown that a significant relationship exists between lower self-concept, self-esteem, and depression in menopause (2, 12). Some women experience a sense of loss at menopause, such as a loss of femininity (21, 39, 48, 61), which is due to hormonal imbalances, changes to reproductive potentials, and changes to body physiology (3, 6). Additionally, a loss of sexual attractiveness, loss of beauty, sense of emptiness, and loss of a maternal role are important causes of a loss of femininity and depression (12, 39, 50, 60).

3.3. Social

Although psychological factors are more frequently assessed in relation to depression in the menopause, several important social changes are strongly associated with the onset of depression in the menopausal period (4, 58). Due to the fact that the menopausal transition often coincides with important life events (6), women might experience a shift in their roles, responsibilities and relationships (4, 39, 47, 57). These social changes include stressful life events (1, 2, 21, 27, 28, 38, 41, 57), the stress of caring for adolescent children or changes in the family structure such as children leaving home, which causes the “empty nest syndrome” (2, 4, 8, 12, 13, 25, 44, 48, 56, 60), children failing to go to a university or get a job (11); additional care giving responsibilities of old parents (13, 16, 41, 44, 45); death of parents or decreased physical health of the women or their partner (2, 6, 21, 34, 40, 56, 62); lower socioeconomic status, financial problems, or low family income (11, 21, 25, 26, 34, 40, 41, 43, 62); changes at work such as the absence of employment, inability to work outside the home, and an avoidance of social activities (13, 41, 47, 52, 59, 62); retirement of the woman or their husband (13, 40, 47, 52); and changes in marital status such as divorced, widowed, or marital conflicts (4, 11, 26, 46).

As mentioned above, one of the major family changes that occur around the time of menopause is that of the children leaving home or getting married (61). Empty-nest syndrome, which has been extensively experienced by menopausal women, was considered an important risk factor of depression by many studies (4, 21, 63). Due to the fact that women’s activities are often limited to their home and their families, the loss of their role as a mother is identified as a possible risk factor for depression (5). However, some women considered this change positive, reporting a feeling of relief from dealing with the distress of their children’s problems and worrying about the health and relationships between family members (16, 60).

Social support is a well-known factor affecting women’s general well-being and mental status (3, 38, 41, 59, 64). Low social support, dissatisfaction with role, and conflict in relationships are associated with distress and psychiatric illnesses, especially depressive disorders (41, 47, 56, 57).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the bio psychosocial risk factors of depression in the menopausal transition. Menopause is a biological event occurring in midlife (28). The relationship between menopause transition and being depressed has been widely studied (25, 65). The largest community-based study, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), reported that women in early perimenopause had a higher rate of persistent mood symptoms than premenopausal women (29). Overall, determining the exact relationship between menopause and mood was difficult due to numerous methodological issues, different measurements of mood, different stages of menopause, and other confounding factors (1).

One common factor in the relationship between menopause transition and depression is the hormonal changes that occur during the midlife period (25, 28). One study revealed that depression in menopause occurs due to a decrease in gonadal hormone levels, which subsequently leads to fatigue, loss of sleep, and overnight hot flashes (66). Regarding the role of hormone therapy in the etiology of depression, there are considerably controversial results. One study found that no consistent relationship exists between circulating estradiol or FSH levels and depression (67), while another study declared that early menopause and the use of exogenous hormones (hormone replacement therapy) were associated with the risk of postmenopausal depression (68). However, another study indicated that there may be some benefit to treat mood disorders with estrogen replacement, which can improve menopausal vasomotor symptoms (13).

Psychological perspectives of the menopause include the meanings and definitions of the menopause, appraisals and attributions of symptoms to the menopause, and cognitive, emotional, as well as behavioral reactions to the menopause (1). Most studies indicated that psychological problems experienced during the menopausal period should be considered important and attract more attention due to the fact that they have a direct relation with psychical limitations such as medical diseases and lowered physical health (22). Psychological factors can also modify the experiences of menopausal symptoms, which can affect the possibility of developing depressive disorders. Women with more negative attitudes towards the menopause report more menopausal symptoms (28). Regarding psychological factors, the relation between stress and depression were assessed in prior studies and the results showed a positive relationship (16, 31).

Various studies that have demonstrated the relation between social changes and depression during menopause (3, 47, 69-71) have highlighted dissatisfaction with marital status and family life, loss of social activities, and dissatisfaction with job as significant risk factors of depression (22).

This study has several strengths and limitations. This article is a result of assessing a lot of related articles and can be a good resource for interested researchers in regards to mental health during menopause. In addition, in this review authors assessed articles that were published in a long time bound. The limitation of this study was that the quality assessment of the included studies or the inter-rater reliability was not conducted. Additionally, articles written only in Farsi and English languages were used, and studies written in other languages, even if they were related to the aim of our study, were not included.

| First author | Years | Country | Study Design | Samples | Instruments | Risk Factors of Depression in Menopause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dennerstein L (21) | 1978 | Australia | Review | - | Electronic search | Loss object such as loss of reproductive capacity, hysterical reaction |

| Tinsley EG (15) | 1984 | Florida, USA | Case-control | 39 | Bem sex role inventory (BSR1), Beck’s depression inventory | Degree of acceptance of the traditional feminine role |

| Ballinger SE (71) | 1985 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 123 | Hamilton rating scale (HDS), life event questionnaire for middle aged women (LEQMW) | Stressful life events, distress or psychological stress, previous history of depression |

| Leiblum SR (8) | 1986 | USA | Cross-sectional | 244 | Menopause attitude questionnaire | Pessimistic belief regarding their femininity and sexuality after menopause |

| Beyene Y (14) | 1986 | California, USA | Qualitative | 203 | Interview | Biocultural factors such as environment, diet, fertility patterns and genetic differences, negative perception toward menopause |

| Raup JL (63) | 1989 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | Child living home and empty nest syndrome |

| Ballinger CB (11) | 1990 | Scotland, UK | Review | - | Electronic search | Hormonal changes, loss of reproductive potential, negative cultural view toward menopause, children living home, negative expectations of menopause, lower socioeconomic status, worry about their children’s work, caring old parents, history of psychiatric disorders, medical complaint |

| Avis NE (54) | 1991 | USA | Perspective cohort | 2565 | The center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) | Negative attitude toward menopause, high education, physical symptoms |

| Holte A (69) | 1991 | Norway | Cross-sectional | 2349 | A slightly revised 24-item symptom checklist | negative expectations regarding the menopause, traditional sex-role, having severe menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms, mood lability |

| Hunter MS (38) | 1993 | London, United Kingdom | Review | Electronic search | Psychological distress, severe vasomotor symptoms, past depression, stressful life events, lower socio-economic Status, low social support, decrease health status, surgical menopause, negative belief regarding menopause | |

| Avis NE (40) | 1994 | USA | Longitudinal, cohort | 2565 | The center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) | Experiencing a long perimenopausal period, increased menopausal symptoms, surgical menopause |

| Liao KLM (55) | 1994 | London, UK | Cross-sectional | 178 | Not mentioned | Negative attitude toward menopause, experience somatic and psychological difficulties |

| Liao KL-M (61) | 1995 | London, UK | Cross-sectional | 106 | Women health questionnaire, self-esteem scale, Multi-dimensional health locus of control scale | Low knowledge and negative belief regarding menopause |

| Pearlstein T (26) | 1997 | Rhode Island | Review | - | Electronic search | Surgical menopause, hormonal changes, previous history of affective disorders |

| Perez IR (39) | 1997 | Spain | Cohort | 120 | General health questionnaire, life events and social difficulties schedule (LEEDS) | Low level of social support, stressful life events, dissatisfaction with occupational role, consumption of psychiatric drugs |

| Walter CA (70) | 2000 | USA | Qualitative | 21 | Semi-structured interview | Loss of reproductive capacity, menopausal symptoms, feeling less sexuality attractiveness |

| Olofsson AS (4) | 2000 | Sweden | Longitudinal, cohort | 148 | Interview and menopause symptom inventory (MENSI) | Negative attitude toward menopause, negative mood |

| Liao KLM (53) | 2000 | Cross-sectional | 64 | The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale, self-esteem scale, perceived stress scale, body satisfaction scale | Perceived stress, and low levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction, premature menopause, body dissatisfaction | |

| Borissova A-M (50) | 2001 | Bulgaria | Cohort | 332 | Zung questionnaire | Low social support, social isolation, sexual problems |

| Stephens C (37) | 2001 | New Zealand | Qualitative | 80 | Semi-structured interview | Children living home, increased responsibilities in the home, body changes and discontinuation of menstruation, life events, husband illnesses, physical illnesses such as blood pressure |

| Hardy R (1) | 2002 | London, UK | Cohort | 1572 | Home interview by research nurses | Concurrent life events and past depressive experiences and behaviors, changing hormone levels, experiencing vasomotor symptoms |

| Maartens L (6) | 2002 | Netherlands | Cohort | 8098 | Edinburgh depression scale (EDS) | Decreased hormone level, previous episode of depression, inability to work, financial problems, death of partner, death of a child, transition from pre to perimenopause or transition from peri to postmenopause |

| Stotland N (44) | 2002 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | Change in social roles, fear of aging, negative cultural view, loss of beauty, loss of childbearing, empty nest syndrome, sense of disappointment |

| Birkhauser M (57) | 2002 | Switzerland | Review | - | Electronic search | Hormonal (estrogen) deficiency |

| Anderson D (47) | 2002 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 400 | Short form health survey (SF-36) | Weak health practices, negative attitudes towards menopause, no exercise, higher number of children living at home, low education |

| Bromberger JT (7) | 2003 | USA | Cohort | 3302 | The role-emotional (RE) scale, study short form 36 (SF-36) | Being early perimenopausal, lower educational attainment, premenstrual syndrome, low level of self-perceived health, stressful life events, low social support |

| Steiner M (34) | 2003 | Canada | Review | - | Electronic search | Premenstrual dysphoria, postpartum depression, previous mood disorders, being in perimenopausal period |

| Busch H (60) | 2003 | Sweden | Qualitative | 130 | The symptom checklist-90 rating scale, semistructured interviews | Optimistic view toward menopause |

| Deeks AA (10) | 2004 | Australia | Case report and review | 2 | Interview | Premature menopause, surgical menopause, hormonal changes, negative attitude toward menopause, history of depression, dissatisfaction with partner, low socioeconomic classes, unemployment, smoking, physical inactivity |

| Dennerstein L (51) | 2004 | Australia | Longitudinal, cohort | 438 | The center for epidemiological studies-depression (CES-D) | Low educational level, negative attitudes toward aging, mood, and premenstrual complaint experience and annual mood, poor self-rated health, number of bothersome symptoms, and daily hassles |

| Schmidt PJ (23) | 2004 | USA | Longitudinal, cohort | 29 | Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, modified version of the Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia-lifetime version | Irregularity before the final menstrual period, family history of mood disorder, smoking history, unpleasant events, past history of depression, experience hot flashes, premenstrual syndrome during perimenopausal period |

| Miller AM (67) | 2004 | USA | Cross-sectional | 220 | The center for epidemiological studies-depression (CES-D) | Use of antidepressant medication, cultural differences, immigration, caring from aging parents, health care inadequacies, social disruption, and political instability |

| Cohen LS (49) | 2005 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | History of depression, low social support, increased daily stressor, ignored health related issues, history of premenstrual syndrome, experience severe vasomotor symptoms, children leave home, losing major role of maternity, stressful life events |

| Hvas L (52) | 2006 | Denmark | Qualitative | 24 | Qualitative interviews | Negative expectation and experience in menopause, ambivalence about aging |

| Cohen LS (27) | 2006 | USA | Longitudinal, cohort | 460 | Life experience survey (LES), center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) | History of negative life events, being in perimenopausal period, presence of vasomotor symptoms, history of depression |

| Dawlatian M (18) | 2006 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 460 | Beck depression inventory | History of depression, stressful life events, higher number of children, unemployment, low educational level |

| Hunter M (3) | 2007 | London, UK | Review | - | Electronic search | Hormonal changes, past psychological problems, low educational level, unemployment, lower social class, poor health, stressful life events, higher BMI, smoking, negative attitude toward menopause and aging, surgical menopause, experience severe hot flashes, feeling loss of control, perceived distress, negative expectations toward menopause, low self-esteem, higher level of anxiety |

| Bromberger JT (41) | 2007 | USA | Cohort | 3302 | The center for epidemiological studies-depression (CES-D) | Negative attitudes toward menopause, poor perceived health, and stressful events, low social support, severe hot flashes, early menopause, using psychotropic medications |

| Woods NF (56) | 2008 | USA | Cohort | 302 | The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) | High level of flash, life stress, family history of depression, history of postpartum blues, sexual abuse history, higher body mass index, use of antidepressants |

| Li Y, Yu Q (59) | 2008 | China | Cross-sectional | 1280 | Social support rating scale, The Zung self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), The Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS) | Strait financial status, low social support, dyspareunia and dry vagina, experience hot flashes and sweating, dissatisfaction with family, children fail college or job and divorced or separated. |

| Deecher D (36) | 2008 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | Hormonal fluctuation, history of depression, presence of vasomotor symptoms, history of postpartum depression, irregular menstruation at the first 5 years |

| Parry BL (9) | 2008 | USA | Case report and review | 1 | Electronic search | Previous history of premenstrual syndrome or postpartum depression, being in perimenopausal period |

| Dennerstein L (48) | 2008 | Australia | Case report and review | 1 | Electronic search | Experiencing a long menopausal transition phase, prior levels of depressed mood, bothersome menopausal symptoms, poor self-rated health, negative feelings for the partner, no partner, current smoking habit, low exercise levels, daily stressors, and high stress, involving adolescent children, caring aging parents |

| Bauld R (31) | 2009 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 116 | The Short-form health survey (SF-36), the menopause rating scale, the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21), the social support questionnaire (short-form, SSQ6, the menopause attitude scale, he proactive coping inventory (PCI), the assessing emotions scale | Low emotional intelligence, negative attitude to menopause, experiencing menopausal symptoms, low social support, low proactive coping |

| Al-Azzawi F (32) | 2009 | Spain | Review | - | Electronic search | Hormonal changes, surgical menopause, vasomotor symptoms |

| Shin-Yi Lu (16) | 2009 | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 266 | >The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D); chinese version, the tennessee self-concept scale, the greene climacteric symptom scale, the attitude toward menopause scale | Hormonal changes, hormone replacement therapy, stressful life events, rebellion of their adolescent children, children leaving the home, and illness/death of a spouse, negative attitudes toward menopause, low self-concept |

| Kaulagekar A (12) | 2010 | India | Cross-sectional | 52 | Depth interviews | Loss of femininity, changing notions about social role |

| Timur S (22) | 2010 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 685 | Beck depression inventory (BDI II) | Being peri/postmenopause, having negative life events compared to not having negative events, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 compared to < 25 kg/m2 |

| Bromberger JT (29) | 2011 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | Vasomotor symptoms, being a current smoker, low social support, very stressful events, financial strain, having less than a college education and higher body mass index (BMI) |

| Humeniuk E (33) | 2011 | Poland | Cross-sectional | 746 | Beck’s depression inventory (BDI) | Lower educational level, dissatisfaction with sex life, unemployment, low family support, unmarried, sense of loneliness |

| Strauss JR (65) | 2011 | USA | Longitudinal, cohort | 986 | Self-administered questionnaire | Severe menopausal symptoms |

| Asadi M (20) | 2012 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 134 | Demographic questionnaire | Hot flashes, mood swing and sexual problems such as vaginal dryness |

| Llaneza P (2) | 2012 | Spain | Review | - | Electronic search | Stress, lower educational level, ethnicity, death of partner, severe comorbid conditions, surgical menopause, abrupt hormonal changes, lower family support, loss of reproductive capacity, bilateral oophorectomy |

| Judd FK (25) | 2012 | Australia | Review | - | Electronic search | Hormonal changes, experience vasomotor symptoms, loss of femininity, negative attitude toward menopause, history of postpartum depression, previous history of premenstrual syndrome, physical health problems, psychological-social stress, past history of depression |

| Colvin A (46) | 2012 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | Loss of job, stressful life events, chronic stress, low social support, widowed, marital conflicts, interpersonal events, low socioeconomic status, childhood sexual abuse, poverty, weak health behaviors, chronic medical diseases, low physical activity |

| Wang H-L (30) | 2013 | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 566 | The center for epidemiological studies-depression scale (CES-D) | Negative attitudes toward menopause and aging, lower family income, younger age, smoking for a greater number of years, consuming more alcohol, having multiple chronic diseases, not exercising regularly |

| Vivian-Taylor J (28) | 2014 | Australia | Review | - | Electronic search | Presence of severe and persistent vasomotor symptoms, previous history of depression, surgical menopause, unpleasant life events, negative attitude toward menopause and aging, lower educational level, consumption psychotropic drugs, lower physical activity, sleep disturbance, marital stress, family violence, premature menopause, higher hormonal fluctuation during menopausal transition |

| Freeman EW (58) | 2014 | USA | Cohort | 203 | The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) | History of depression, current smoker, current medications, hormonal changes |

| Borkoles E (43) | 2015 | UK | Cross-sectional | 213 | The center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale (CES-D), the women’s health questionnaire (WHQ) | Severe vasomotor symptoms, previous history of depression, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, hormonal changes |

| Chou C-H (24) | 2015 | Taiwan | Cohort | 190 | Menopausal symptoms scale, neuroticism extraversion openness five factor inventory—chinese version, Ko’s depression inventory were applied | History of major depressive disorder (MDD), vasomotor symptoms, and neuroticism |

| Freeman EW (42) | 2015 | USA | Review | - | Electronic search | Baseline negative mood, Prior negative mood, history of premenstrual complaints, negative attitudes toward aging or menopause, poor health, and daily hassles, life stress, body mass index, history of postpartum blues, and use of antidepressants, upsetting life events and medication use |

| Afshari P (66) | 2015 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 1280 | Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) | Illiteracy, employment |

| Jung SJ (68) | 2015 | Korea | Cross-sectional | 276 | Interview | Earlier menopause, greater numbers of pregnancies and exogenous hormone, manual working class, low educational level, hormonal changes, negative effect on sexual life, postpartum depression |

| Sassarini J (13) | 2016 | UK | Review | - | Electronic search | Previous history of premenstrual syndrome, history of postpartum depression or postpartum blues, changes in family structure, empty nest syndrome, caring old parents, retirement, hormonal changes, low social support, stressful life events, financial strain, higher BMI |

| Worsley R (45) | 2017 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 2020 | Menopause specific quality of life questionnaire, the beck depression inventory-II | Vasomotor symptoms, higher BMI, have no partner, caring family, unsafe housing status, lower educational level, unemployment |

4.1. Conclusions

Women in midlife face an increased risk of low mood and depression. The results of many studies focusing on the link between depression and menopause indicate that a number of biological, psychological, and social risk factors affect the occurrence of depression during the menopausal period. Given the importance of women’s psychological health in their midlife period, this study recommends that the mental health of midlife women, particularly those at a high risk of depression, should be evaluated by physicians in menopausal clinics. In addition, every psychological disorder should be referred to a psychiatrist for pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions.

4.1.1. Application in Research

This study can be a source for researchers to be aware about the results of a lot of studies regarding risk factors of depression in menopausal periods. In order to give the mentioned limitations, the authors of this study proposed that a systematic review or meta-analysis regarding the risk factors or contributing factors of depression in menopausal women to identify the most important risk factors of depression in this period would be a good action.

4.1.2. Application in Practice

Given the important role of mental health in women's quality of life, considering the psychological screening in the menopause clinic along with physical screening are recommended and lead to increase in psychological well-being.