1. Background

Given the increased life expectancy and decreased births in most areas of the world, the population of older adults is growing worldwide, with the proportion of people aged 65 years and above rising from 8% to 8.5% only over a three-year (2012 - 2015) period (1). Iran is currently undergoing a transition in its population age structure from youth to older adulthood. Thus, the improved life expectancy and predicted increase in the number and proportion of older adults (population aged ≥ 65 years) in Iran in future years (2) further underline the necessity of implementing prospective programs to manage the problems in this population group. In this respect, attention to various life aspects of this population group, including well-being and life satisfaction, seems essential and significant.

As a core measure of mental health (3), life satisfaction evaluates the individual’s overall perception and attitude toward his life. This important psychological index is positively associated with well-being, quality of life, hope, and meaning of life. Therefore, given the studies suggesting the impact of aging on reducing life satisfaction (4), it is necessary to evaluate its associated factors and understand how to promote life satisfaction in older adults.

Previous studies have identified some factors related to life satisfaction, including health, employment status, personal traits, and ethical values. In this regard, one of the contributory factors is social communication between individuals, which refers to their contact with each other through conversations, actions, and mutual reactions. Based on the social support theory, people with appropriate social communication receive higher social support in coping with their life challenges, eventually causing their enhanced psychological well-being and life satisfaction (5).

Intergenerational communication is one of the most significant forms of social communication among older adults. Considering intergenerational relationships as the relationship between the people of two or three successive generations (6), intergenerational communication refers to communication between older adults and younger generations. Intergenerational communications have been shown to influence older adults’ life satisfaction and mental health (7). Despite their positive outcomes for older adults, intergenerational communications can cause negative outcomes if they include any negative content or message to the older audience. According to the Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT), the communication between older adults and young people can be either positive and accommodative or negative and non-accommodative (8).

Intergenerational accommodative communication (IAC) is a prosocial and positive communication strategy. In this type of intergenerational communication, older adults consider the young people as respectful and supportive, allowing them to feel valued and respected. Conversely, intergenerational non-accommodative communication (INAC) is an anti-social and negative communication strategy. Older adults perceive these communications as annoying, in which they are neglected and may even be treated imperiously and inferiorly (9). Studies have highlighted the significant positive effect of intergenerational accommodation and the significant negative impact of intergenerational non-accommodation on life satisfaction, self-esteem, efficacy, and positive emotions toward aging (9-11). Nevertheless, a paucity of studies compared the significance of accommodative and non-accommodative communication on life satisfaction in older adults.

However, apart from the process of intergenerational communication that can be accommodative or non-accommodative, individual characteristics may also be effective in the relationship between intergenerational communication and the life satisfaction of older adults. According to the Affective Expectation Model (AEM), as emotional expectations determine people’s emotional experiences, people perceive and experience more of what they expect (12). Therefore, it can be said that people who have positive expectations of intergenerational interactions also experience positive emotions and consequences from it. In psychology, having positive expectations and hope for the future is defined as optimism. Optimistic people use a tendency or explanatory style to interpret their life events. When faced with negative life events, they consider the reason beyond their control or attribute it to the fault of others (13). Also, compared to pessimistic people, they experience fewer negative emotions such as stress, anxiety, and sadness. Therefore, it can be claimed that optimistic people with positive expectations from events will eventually understand and experience positive consequences from them. Thus, optimism or pessimism of the individuals in interpreting intergenerational communication can enhance the effect of accommodative communication, alleviate the effect of non-accommodative communication, and affect the intergenerational communication outcome and, ultimately, life satisfaction.

Studies have highlighted optimism toward aging (OTA) as a critical optimism dimension during older adulthood that can be an effective variable in the association between intergenerational communication and successful aging (9). However, to the authors’ knowledge, no study in Iran has been conducted to assess the impact of OTA on the relationship between intergenerational communication and life satisfaction.

2. Objectives

Today in most cultures, young people have inappropriate and mostly non-accommodative communication with older adults (11). Iran is an aging country in which social norms and family values are evolving drastically. In recent years, the relationships between Iranian parents and their children are becoming more economized (14), and these changes can affect the intergenerational communication of older adults. Thus, studying intergenerational communication and its life satisfaction outcome in Iranian older adults seems of utmost importance. The present study focused on the association between accommodative and non-accommodative communication and life satisfaction in older adults while evaluating the effect of OTA, as a mediating variable, on their life satisfaction. This study seeks to answer the following questions. First, is accommodative or non-accommodative communication associated with life satisfaction in Iranian older adults? Second, can OTA mediate the relationship between intergenerational communications and life satisfaction in older adults and change their effect on life satisfaction?

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was performed on 550 individuals aged 60 or older in Bojnord, Iran, from winter 2021 to spring 2022. Considering Bojnord City’s segmentation into seven districts, the sampling was conducted using a multistage cluster sampling method. Each city district was considered a cluster, and the sample size in each cluster was determined by the quota sampling method. Next, two neighborhoods were randomly selected from each district. Then, the interviewers (two men and five women with bachelor’s degrees in social sciences or psychology) entered the selected districts and completed the questionnaires with community-dwelling older adults through face-to-face interviews. The interviewers described the purpose of the study for older adults. Then, individuals who could speak and adequately communicate with the interviewers entered the study. Researchers obtained informed consent from the participants and ensured the confidentiality of their data. The exclusion criteria were dissatisfaction with participating in the research and an incomplete questionnaire. The participants were allowed to leave the study at any time at their will.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Independent Variables: Intergenerational Communication

This variable was measured using the intergenerational communication scale based on Gasiork and Fowler’s study (9). It has two dimensions, Intergenerational Accommodative communication (IAC) and Intergenerational Non-accommodative communication (INAC). Each dimension has 6 questions, such as, “Young people are generally helpful to people my age and me,” and Young people order people my age and me.” It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from completely agree to completely disagree. Its validity was checked and confirmed in Iran (15), and its reliability in the present study was found to be 0.87 in the dimension of IAC and 0.89 in the dimension of INAC (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

3.2.2. Mediating variables: Optimism Toward Aging

Older adults face changes and limitations related to aging, and their optimism or pessimism about the future can completely depend on their circumstances during this period. So, it is better to check their optimism based on the scales specifically measuring their optimism towards aging. Therefore, in the present study, this variable was measured with the Optimism Toward Aging (OTA) scale based on Fowler et al.’s study (16). It has 6 questions, such as “I frequently express the fact that I am optimistic about aging.” It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from completely agree to completely disagree. Its validity was checked and confirmed in Iran (15), and its reliability in the present study was found to be 0.91 (Appendix in Supplementary File).

3.2.3. Dependent Variables: Life Satisfaction

Given that responding to short questionnaires is more suitable for older adults, the single-item Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS-1) was applied to assess life satisfaction in older adults. This scale is widely applied in the literature to evaluate life satisfaction in older adults (17, 18). It includes a single-item measure, “How satisfied are you with your recent life as a whole?” The responses ranged from 0 (extremely dissatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied). It is especially suitable for surveys, where the number of questions is important for the study participants. The psychometric properties of this scale have been verified in Iran (19).

3.3. Control Variables

These variables included age, gender, marital status (married/single), level of education (illiterate/ primary school/ middle school/ high school diploma or higher), and the number of diseases (without disease, one disease, two diseases, and more than two diseases).

3.4. Statistical Methods

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using maximum likelihood estimation was adopted with Amos 24.0 to test the hypothesized models. The analyses were done in two stages. First, we tested the measurement model through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and examined all factor loadings. Then, in the second stage, the structural model was verified to examine whether the research hypotheses could be empirically supported. The indicators of acceptable structure validity of model fit included comparative fit index (CFI) values above 0.90 (20), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.08, and relative chi-square (χ2/df) of 5 or less (21). Moreover, to examine the mediation effect of optimism toward aging on the association between intergenerational communication and the life satisfaction of older adults, bootstrapping (n = 2000 bootstrap samples) was employed (22).

4. Results

The mean age of the participants was 67.74 ± 7.18, and the maximum age was 93. Among them, 240 people (43.6%) were men, and 371 (68.9%) were married. More descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

| Demographic Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 240 (43.6) |

| Women | 310 (56.4) |

| Age | |

| 60 - 70 | 394 (71.6) |

| More than 70 | 156 (28.4) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 179 (32.5) |

| Primary school | 166 (30.2) |

| Middle school | 73 (13.3) |

| High school diploma or higher | 132 (24) |

| Number of diseases | |

| Without disease | 120 (21.8) |

| One disease | 149 (27.2) |

| Two diseases | 170 (31) |

| More than two diseases | 111 (20) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 384 (69.8) |

| Single | 166 (30.2) |

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 550)

Table 2 shows that IAC and OTA had a significant positive relationship with life satisfaction (LS), while INAC had a significant negative relationship with LS.

To investigate the association between study variables and LS, we gathered all the control variables, latent variables, and their observed variables into the structural equation model to verify the structural model and test the conceptual framework proposed. All factor loadings in the measurement model ranging from 0.59 to 0.89 were statistically significant at the 0.001 level. The structural model well fitted the data (χ2/df = 3.19, RMSEA = 0.063 [90%CI = 0.058, 0.066], CFI = 0.94). Among all the control variables involved in this study, gender (β = 0.116, P = 0.005) and education level (β = 0.298, P < 0.001) significantly affected the LS of older adults. The results showed that the LS was higher in females than males, and higher levels of education predicted a higher LS.

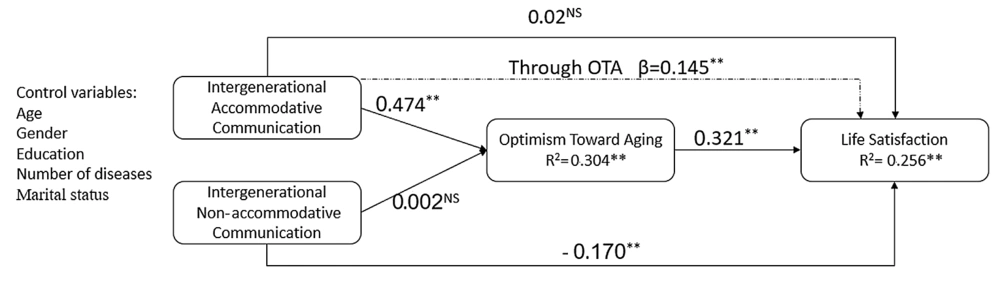

According to Figure 1, IAC had no significant direct association with LS (β = 0.02, P = 0.70), but INAC had a significant negative direct association with it (β = -0.170, P < 0.001). With INAC increasing by one standard deviation, life satisfaction decreases by 0.170 standard deviations. In addition, unlike INAC, IAC had a significant direct association with optimism toward aging (β = 0.474, P < 0.001). Also, OTA had a significant direct association with LS (β = 0.321, P < 0.001). Nevertheless, because INAC did not directly correlate with OTA (β = 0.002, P = 0.62), mediation effects were only examined for IAC. Therefore, we employed a bootstrapping strategy with the 2000 samples created using random sampling from the original dataset to test the indirect association of IAC with LS through optimism toward aging as the mediator. The results revealed that the indirect association of IAC with LS in older adults through OTA was significant (β = 0.145, CI = [0.100, 0.199], P < 0.001). Also, in this model, the total effect of IAC (β = 0.125, CI = [0.036, 0.204], P = 0.024) on LS in older adults was significant.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to answer the following questions: Is accommodative or non-accommodative communication associated with life satisfaction in Iranian older adults? Can OTA mediate the relationship between intergenerational communications and life satisfaction in older adults and change their effect on life satisfaction?

The findings suggested a relationship between gender and education level and life satisfaction in older adults, with female gender and higher education predictive of higher life satisfaction. Inconsistencies exist regarding the relationship between gender and life satisfaction. For instance, in line with the present study, a Chinese study found significantly higher life satisfaction in women than men (23). Conversely, some studies have established higher life satisfaction in males than females (24, 25). Others have reported no significant relationship between gender and life satisfaction (4). Overall, given that life satisfaction is an intricate and multifactorial concept, many other factors can influence the relationship between gender and life satisfaction (25-27). In this study, higher education level was predictive of higher life satisfaction which agrees with other studies conducted in Iran and China (4, 25, 28). However, some studies have suggested a negative relationship between life satisfaction and education, which is explained by better self-evaluation of health in older adults with low education levels, resulting in higher life satisfaction (27). However, based on the results of the present study, promoting life satisfaction in male and less-educated older adults requires further attention from planners and policy-makers.

In the present study, INAC and IAC were significantly correlated with LS. However, after introducing the OTA variable to the analysis and controlling for the demographic variables, no significant and direct association was found between IAC and LS. Still, INAC showed a significant negative relationship with LS. This observation is consistent with Keaton et al.’s study on Thai and American older adults (11). According to this result, older adults will have lower life satisfaction if intergenerational communication is non-accommodative, making them feel neglected or inferiorly treated by younger people. Other studies have highlighted that INAC causes negative consequences, including reduced self-efficacy, in older adults (9, 10). Besides, given the lack of a direct relationship between IAC and LS, it can be concluded that INAC has a larger effect on life satisfaction than IAC. Other studies have also demonstrated that successful aging perception, depression, loneliness, and self-efficacy in older adults are more affected by INAC than IAC (9, 29). In other words, negative social interactions have more consequences in older adults than positive social interactions (30). Thus, this issue must be addressed in the social relationships between young people and older adults.

In the current study, the individuals experiencing higher IAC demonstrated higher OTA. Other studies also suggested that appropriate intergenerational communication can improve optimism in older adults (31). However, INAC showed no significant association with OTA. Consistent with the current study, Gasiorek and Fowler revealed that IAC, but not INAC, has a significant positive association with OTA (9). It can be stated that optimism is affected by positive life events and is not associated with negative events (32), meaning that negative events cannot influence it.

In this study, older adults with higher OTA showed higher LS, which agrees with the results of other studies (33, 34). The reason is that optimist individuals adopt a more positive attitude toward their lives, thereby experiencing more life satisfaction. Introducing OTA as a mediating variable in the analysis revealed that the indirect association between IAC and LS was positive and significant. Other studies emphasized that optimism in older adults can be an excellent mediator in promoting their well-being (31) and life satisfaction (35). Nevertheless, although OTA could mediate a positive relationship between IAC and LS, it failed to change the negative association between INAC and LS due to its non-association with INAC. Thus, given the obtained evidence suggesting the significance and role of OTA and intergenerational communication in the life satisfaction of older adults, more attention should be paid to these variables in future planning and policy-making on the mental health and well-being of older adults.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings demonstrated an association between life satisfaction in older adults and intergenerational communication, verifying the stronger effect of intergenerational non-accommodative communication, so an increase in non-accommodative communication reduces life satisfaction. In addition, the relationship between accommodative communication and life satisfaction will be non-significant without the mediating effect of optimism toward aging. Nevertheless, optimism toward aging failed to mediate the relationship between non-accommodative communication and life satisfaction in older adults. Therefore, to enhance life satisfaction in Iranian older adults and improve their attitude toward aging, giving special attention to their communication with young people is necessary. Counseling intervention must be considered for families with older adults, particularly male and less-educated older adults.

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions

One limitation of this study was its cross-sectional design which does not allow a thorough evaluation of the cause-and-effect relationship. Thus, prospective studies are essential to explore further the effect of intergenerational accommodative and non-accommodative communication on older adults. Another limitation was that the sample only included older adults in urban communities and excluded those living in rural areas, nursing homes, or hospitalized in hospitals. However, the conditions of this group of older adults may affect intergenerational communication and its outcomes and alter the study results. Thus, future studies should address this population of older adults.