1. Background

Although there are different views about perfectionism, and a uni-dimensional conceptualization of perfectionism has been prominent for a long time, several multidimensional models of perfectionism have been suggested in recent decades (1). During their 30 years of research, Hewitt et al. have conceptualized perfectionism as “a multidimensional and multi-level personality construct” with deep roots in personality traits and interpersonal, intrapersonal, motivational, and behavioral manifestations. According to the comprehensive model of perfectionistic behavior, perfectionism consists of three components: perfectionistic traits, perfectionistic self-presentation styles, and information processing or perfectionistic cognitive processes, all of which contribute to a stable and persistent trait that drives perfectionism (2).

In their model, perfectionism traits are composed of three separate dimensions: (1) Self-oriented perfectionism (the desire for perfection in oneself); (2) other-oriented perfectionism (the need for perfection in others); (3) socially prescribed perfectionism (the perception that others require perfection of oneself).

Perfectionistic self-presentational styles, which represent interpersonal expression and communication, refer to how an individual represents himself/herself as a perfect person to others. Finally, the intrapersonal or perfectionism information-processing component represents the activation of an ideal self-schema, which is reflected in automatic perfectionistic thoughts (2).

Research using this multifaceted conceptualization of perfectionism has shown that these components are independent of each other (3, 4). Moreover, it has been reported that there is a strong and precise relationship between different components of perfectionism and various types of psychopathology. Several studies have found that these dimensions are strongly linked to a variety of psychopathologies, including shame vulnerability (5), self-criticism (6), low self-esteem (7), depression and anxiety symptoms (8), suicidal ideation (9), and eating disorders (10).

The present study focuses on perfectionistic self-presentation based on criteria developed for adults. Perfectionistic self-presentation is a concept derived from the observation that some perfectionists feel the need to appear perfect, even when they perceive themselves as far from perfect. Therefore, they hide behind a mask of excellence and perfection. Hewitt et al. introduced perfectionistic self-presentation as a form of interpersonal expression (2). The construct of perfectionistic self-presentation is related to a person's interpersonal goals and desires, reflecting an attempt to portray the self favorably in interactions with others. A literature review has shown that perfectionistic self-presentation may indirectly affect psychopathology by influencing maladaptive coping in the face of stressors and is related to poor adaptation and interpersonal problems (11, 12).

As Hewitt et al. argue, a thorough and comprehensive assessment of perfectionism can provide clues and hypotheses for key themes, formulation components, and issues that should be addressed as part of the treatment process (2). Researchers in this field have developed a variety of scales to assess levels and manifestations of perfectionism. The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) is one of the most widely used scales in research, analyzing the trait dimensions of perfectionism based on the comprehensive model of perfectionistic behaviors (13). Another helpful tool, developed by Flett et al., is the Perfectionistic Cognitions Inventory (PCI), which identifies automatic perfectionistic cognitions and ruminations about mistakes and defects regarding perfectionistic behavior (14). According to reviews, the Persian versions of the MPS and PCI were translated and psychometrically evaluated by Besharat (15, 16). Another tool used in perfectionism research is the Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale (PSPS), which includes 27 items and was introduced for the first time by Hewitt et al. (3).

The Perfectionistic PSPS was developed to assess the extent to which individuals are concerned with appearing perfect to others and avoiding displays or disclosures of their perceived imperfections. More precisely, the PSPS includes three subscales: (1) Perfectionistic Self-Promotion, which involves a need to elevate oneself to the level of perfection through an active and unrealistic expression of one’s perfection; (2) non-display of imperfection, which refers to an avoidant behavioral style aimed at concealing any imperfect behavior; and (3) non-disclosure of imperfection, which involves avoiding verbal expression of any imperfections (2). These facets represent both promotional and concealing components of perfectionistic self-presentation.

The interpersonal expression of perfectionism is particularly relevant to the entire clinical process of seeking help, accessing help, compliance, and staying the course in treatment. Obtaining specific information regarding these styles of interpersonal behavior can become the focus of process comments and therapeutic work, which can help to forestall early termination or noncompliance (17).

Hewitt and Flett developed an initial pool of 71 items capturing the broad domains of perfectionistic self-presentation (18). The statements were evaluated on a 7-point Likert Scale. Items were dropped if the item mean was greater than 5 or less than 3, if the standard deviation was less than 1.00, or because of duplication of content or inappropriate wording. Through principal component factor analysis with Varimax rotation, they obtained three factors: Perfectionistic Self-Promotion (10 items), non-display of imperfection (10 items), and non-disclosure of imperfection (7 items). In their study, the structural validity, differentiation, and predictive validity of the subscales were demonstrated, and a high degree of internal consistency was found for the subscales. Test-retest coefficients also indicated that PSPS facets have relatively high levels of stability in both student and clinical samples (19).

This scale has been validated in different versions. For example, it was found that the internal consistency reliability estimates for the total score and the subscales of the Italian version of the PSPS were adequate (20). This conclusion was based on an analysis of 447 adult volunteers. The original three-factor structure for PSPS items was confirmed by both dimensionality analyses and the WLSMV exploratory structural model. Another study conducted on the Portuguese validation of the PSPS in 286 students showed that the Portuguese version of the PSPS has good reliability and validity, with the factorial model presenting an acceptable fit (21). This scale has also been validated in versions related to children and adolescents in a junior form (22). The results of these studies have shown that this scale has acceptable validity and reliability and is considered a stable and strong factor in personal and interpersonal psychological distress.

2. Objectives

According to reviews, the PSPS has strong theoretical and research support. Since the Persian version of the PSPS is not available to date, the present study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the PSPS in an adult sample. Moreover, this research investigates its relationship with perfectionism, compassion, stress, anxiety, and depression in an adult sample. In addition to expanding knowledge about perfectionism, this research provides researchers in Iran with a reliable tool. This tool can help clinicians, psychotherapists, and researchers evaluate the relational aspects of perfectionism, especially in the adult population.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Research Procedure

The present study is in the field of psychometric research and correlational analysis. Given that there were 27 items on the PSPS and at least 10 samples needed to be evaluated for each item, 332 people were sampled, and the data collected from these individuals were analyzed and evaluated. The research samples consisted of adult volunteers living in Tehran in 2019, with an age range of 18 to 53 years. The sampling method was targeted and readily available.

It should be noted that, due to the conditions following the COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide quarantine, face-to-face access to the research participants was impossible at the time of the study. For this reason, the questionnaires were created on an internet platform, and volunteers were sent the link to participate in the research. Each questionnaire was assigned a numerical code, and the results were analyzed in groups.

Permission was obtained from the developers of the tool via email to conduct research and examine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of this scale. Inclusion criteria included age over 18 years, at least a diploma-level education, and consent and willingness to participate in the research.

In the first step, to investigate the psychometric properties of the PSPS, the original version of the scale was translated into Persian by two individuals fluent in English and Persian (one familiar with psychological concepts and the other a master in translation). In the second step, the initial translations were combined into a single translation by a fluent translator in both languages, resulting in the final Persian version. In the third step, the final translation was back-translated into the original language by two other translators proficient in both languages. In the final step, the revised version was administered to a small sample of students (20 people) to examine their understanding of the materials.

Two methods, qualitative and quantitative, were used to determine content validity, including the judgment of clinical psychologists, counselors, and psychiatrists. To ensure content validity qualitatively, experts were asked to provide feedback after reviewing the quality of the tool based on criteria such as grammar, appropriate word usage, proper item placement, and appropriate scoring. After collecting the responses, the necessary corrections were made.

To quantitatively assess content validity, the content validity ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI) were employed. First, to determine the CVR, 15 experts reviewed each question using a 3-point Likert Scale (necessary, useful but not necessary, and not necessary). A value above 0.49 was considered acceptable according to the number of evaluators (15 specialists) (23). Then, the CVI was examined separately by experts using a 4-point Likert Scale for each item (1. unrelated, 2. somewhat relevant, 3. relevant, and 4. completely related). The CVI score was calculated by summing the agreeing scores for each item ranked as third and fourth, divided by the total number of experts. An item was accepted if the CVI score was higher than 0.79 (24).

To assess the face validity of the instrument, the questionnaire was provided to 10 clinical psychologists and experts in the field of psychology. They qualitatively investigated the level of difficulty, disproportion, ambiguity of phrases, or inaccuracies in the meanings of each item's words. The experts assessed the questionnaire in terms of ease of understanding, clarity, and appearance. Their corrective comments were applied at the end of the review process.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale

The PSPS is a 27-item measure of three dimensions of perfectionistic self-presentation: Perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfection, and nondisclosure of imperfection. Perfectionistic self-promotion is captured with a 10-item subscale (e.g., “I try always to present a picture of perfection”); higher scores on this subscale indicate higher levels of a perfectionistic self-presentational style characterized by the need to brashly promote oneself as perfect to others. Nondisplay of imperfection is measured with a 10-item subscale (e.g., “It would be awful if I made a fool of myself in front of others”), with higher scores indicating a higher level of a perfectionistic self-presentational style characterized by the need to avoid behavioral demonstrations of one’s imperfection. Nondisclosure of imperfection is assessed with a 7-item subscale (e.g., “Admitting failure to others is the worst possible thing”); high scores on this subscale indicate high levels of a perfectionistic self-presentational style characterized by the need to avoid verbal disclosures of one’s imperfection. Participants responded to the items of the three subscales using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Subjects rate their agreement, with higher scores indicating greater perfectionistic self-presentation (18). Several studies have supported the multidimensionality, internal validity, test-retest validity, predictive validity, convergent validity, incremental validity, and diagnostic validity of this instrument (25). Evidence supports both the reliability and validity of the PSPS (19).

3.2.2. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale

Dimensions of perfectionism were measured by the Persian version of the MPS. This scale consists of 30 items divided into three dimensions: Self-Oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism. It is based on a 5-point Likert Scale. Cronbach’s alpha in the Persian form for self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism was 0.92, 0.87, and 0.84, respectively. Test-retest scores over a four-week interval for self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism were 0.88, 0.83, and 0.80, respectively (15).

3.2.3. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale

This scale was developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (26). The DASS provides a more precise distinction between depression and anxiety compared to other available scales. It has two forms: A short form with 21 items, and a long form. In the short form, each of the 7 items measures one factor, with items scored on a 4-point Likert Scale from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much). The Persian version of the short form of the DASS has been standardized, with internal consistency coefficients reported as 0.70 for depression, 0.66 for anxiety, and 0.76 for stress (27).

3.2.4. Self-Compassion Scale

This self-report scale has 26 items and is based on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always). It measures three bipolar components in the form of six subscales: Self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification (28). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the six subscales were 0.77, 0.72, 0.72, 0.80, 0.74, and 0.74, respectively, and the total reliability coefficient by the test-retest method has been reported as 0.93. Additionally, Yarnell and Neff reported that this scale has high convergent and discriminant validity (29).

3.3. Data Analysis

The data were refined and screened, with missing data comprising less than 5% of the dataset. As a result, listwise deletion without imputation was used in the analyses. Decisions to remove or retain outliers were based on comparing the original mean with the 5% trimmed mean. Normality assumptions were checked, and skewness was not evident in the total scale score in the normative group. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was chosen to assess the fit of the three-factor model, with model parameters calculated using maximum likelihood.

Divergent and convergent validity were assessed using Pearson correlation tests between PSPS and TMPS, DASS, and SCS scores. The reliability of the three subscales of the PSPS and the total scale score was evaluated by determining internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha coefficient.

The fit of the model was evaluated using the following indexes: The normal chi-square, Normed Fit Index (NFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted GFI (AGFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The acceptability of CFA fit indexes is indicated by RMSEA coefficients less than 0.08, SRMR less than 0.10, and fit indexes CFI, GFI, AGFI, IFI, RFI, NFI, and NNFI above 0.90, with AGFI above 0.85. SPSS version 22 and LISREL version 8.80 were employed for data analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Participants

In the present study, 332 adults ranging from 18 to 40 years old participated, with a mean age of 28.92 ± 7.04. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 126 (38) |

| Female | 206 (62) |

| Education | |

| Diploma | 18 (5.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 102 (30.7) |

| Master’s degree | 154(46.4) |

| Ph.D. degree | 58(17.5) |

Profile of Participants

The mean and standard deviation of the PSPS total score were 99.61 ± 28.68. The results of the t-test for independent groups showed that men (104.74 ± 28.31) scored significantly higher than women (96.47 ± 28.53) on the PSPS total score (t (407) = -2.568, P = 0.011). Additionally, the results of multivariate variance analysis showed a significant difference between men and women in PSPS subscales [F (3,328) = 3.99, P = 0.008; partial Eta squared = 0.03].

4.2. Content Validity

Experts' opinions led to changes in the scale's content following a qualitative review. Additionally, CVR and CVI were used to assess content validity, with values of 0.7 and 0.8, respectively. These values are higher than the acceptable levels [0.49 for CVR according to the number of evaluators, 15 specialists, and 0.79 for CVI (30)], indicating that this scale has content validity.

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

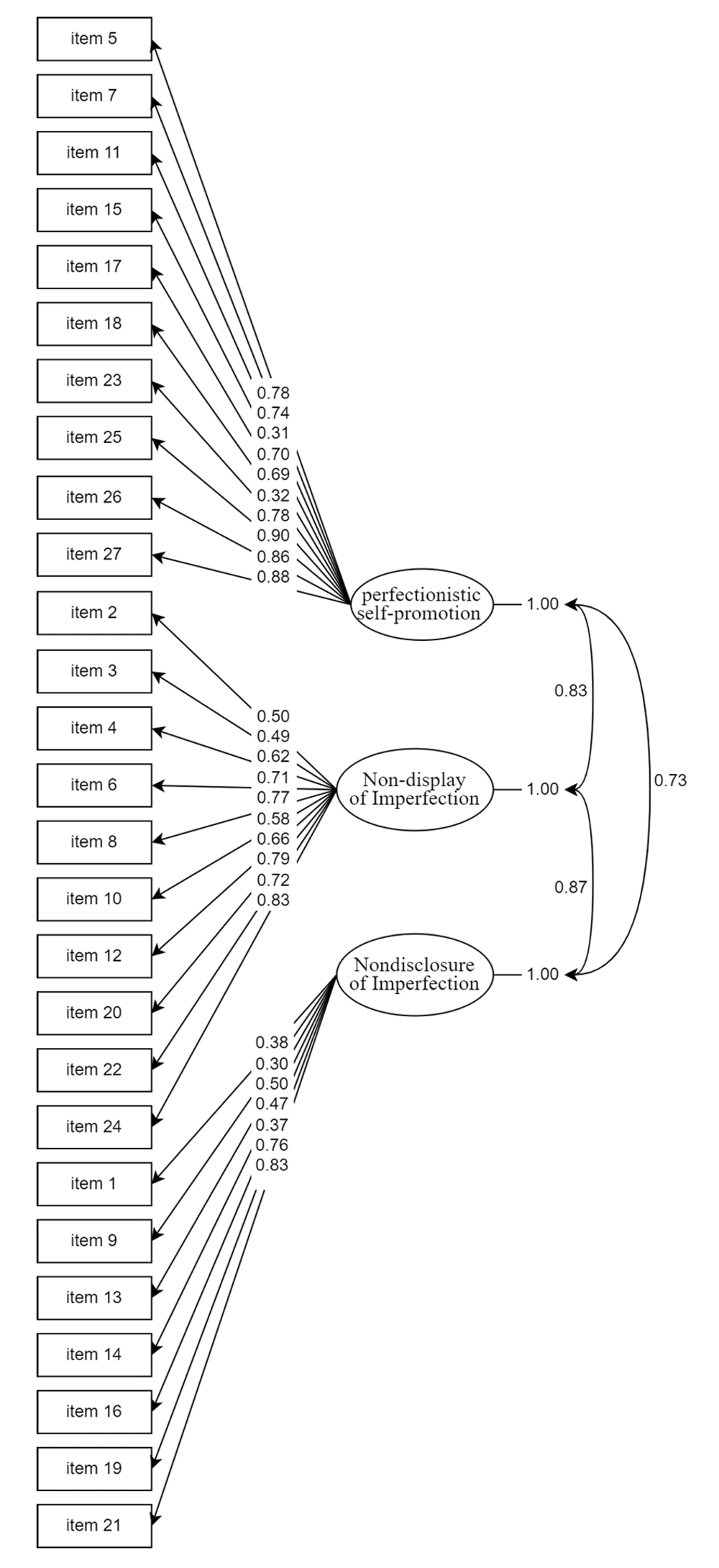

The results of the goodness of fit indexes for the three-factor model of PSPS and the factor loadings for each item of PSPS are presented in Table 2. Based on the standardized factor loading values, the significance of t, and the acceptable goodness of fit indexes, it can be concluded that the confirmatory model of the PSPS scale has an acceptable goodness of fit for the three-factor model (Table 2, Figure 1).

| Items and PSPS Subscales | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Perfectionistic Self-Promotion | |

| 5. I always try to present a perfect image of myself. | 0.78 |

| 7. If I look perfect, people evaluate me more positive. | 0.74 |

| 11. No matter if there is a defect in my appearance. | 0.31 |

| 15. It's necessary to look that I always control my actions. | 0.70 |

| 17. It is important to a perfect function in social situations. | 0.69 |

| 18. I don't care to be decent perfectly. | 0.32 |

| 23. I need to seem completely capable while doing something. | 0.78 |

| 25. It's so important to always look the best among others. | 0.90 |

| 26. I should always seem perfect. | 0.86 |

| 27. I always try to look perfect in the eyes of others. | 0.88 |

| Non-display of imperfection | |

| 2. I evaluate myself based on mistakes I make against others. | 0.50 |

| 3. I do whatever to conceal my mistakes. | 0.49 |

| 4. Mistakes and faults is worse when accrue in presence of people rather than in personal privacy. | 0.62 |

| 6. It is so unpleasant if I would show an idiotic image of myself. | 0.71 |

| 8. I think very much about mistakes I have done in presence of others and I become anxious. | 0.77 |

| 10. I want to look more competent that I am actually. | 0.58 |

| 12. I don't want to people see me while I am doing something, except I am doing well. | 0.66 |

| 20. I hate to error in the crowd. | 0.79 |

| 22. I don't care to make a mistake in the crowd. | 0.72 |

| 24. It's so unpleasant when others notice my failure. | 0.83 |

| Non-disclosure of imperfection | |

| 1. It's good to show people that I am not perfect. | 0.38 |

| 9. I never let people to know that I try hardly to do my jobs. | 0.30 |

| 13. I should always keep my problems for myself. | 0.50 |

| 14. I should solve my problems and not telling to others. | 0.47 |

| 16. It's OK to accept the mistakes you had against others. | 0.37 |

| 19. It is worse thing to accept defeat against others. | 0.76 |

| 21. I try to keep errors and deficits in myself. | 0.83 |

| Fit indexes (three-factor model) | |

| CAIC | 2508.71 |

| df | 321 |

| X2 | 1712.04 |

| P | 0.001 |

| X2.df | 5.33 |

| SRMR | 0.07 |

| RFI | 0.90 |

| NFI | 0.91 |

| CFI | 0.92 |

| IFI | 0.92 |

| NNFI | 0.92 |

| RMSEA | 0.06 |

Goodness of Fit Indexes

The normal chi-square should be less than 3 for an appropriate model (31), but in our study, χ2 /df was greater than 3 (5.53), indicating a poor fit of the data to the original model. Since chi-square is sensitive to sample size and can overestimate the fitness of the model—because as sample size increases, with constant degrees of freedom, the chi-square value also increases—this can lead to plausible models being rejected (32). Given the higher-than-desirable chi-square value, we used indices not sensitive to sample size, such as CFI, NNFI, SRMR, and RMSEA, rather than chi-square tests. These indices, which are not dependent on sample size, were acceptable. Considering that goodness of fit indexes, including CFI, IFI, NFI, NNFI, and RFI, were higher than 0.90 and SRMR was lower than 0.08, indicating a good fit for the three-dimensional scale model, the factor structure of PSPS was confirmed according to the original version. The closer the CFI, NFI, and RFI are to one, the better the goodness of fit. Although the chi-square index is usually used to evaluate the goodness of fit, it increases with sample size and degrees of freedom. Therefore, the use of RMSEA and SRMR is recommended. The values obtained in these two components indicate the acceptability of fit indexes (33).

4.4. Correlation Between Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale Subscales and Total Score

The results in Table 3 demonstrate a positive and significant relationship between PSPS and its subscales. Based on these results, the correlation range is from 0.54 to 0.94, indicating a high correlation between PSPS and its subscales.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSPS | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Self-Promotion | 0.91 a | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Non-display of Imperfection | 0.94 a | 0.79 a | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Non-disclosure of Imperfection | 0.77 a | 0.54 a | 0.64 a | 1 | |||||

| 5. Self-Compassion | -0.58 a | -0.44 a | -0.58 a | -0.53 a | 1 | ||||

| 6. Multidimensional perfectionism | 0.62 a | 0.67 a | 0.57 a | 0.31 a | -0.33 a | 1 | |||

| 7. Depression | 0.29 a | 0.21 a | 0.27 a | 0.33 a | -0.36 a | 0.14 b | 1 | ||

| 8. Stress | 0.27 a | 0.23 a | 0.27 a | 0.28 a | -0.36 a | 0.13 b | 0.70 a | 1 | |

| 9. Anxiety | 0.25 a | 0.20 a | 0.23 a | 0.25 a | -0.27 a | 0.17 b | 0.68 a | 0.77 a | 1 |

Convergent and Divergent Validity of Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale

4.5. Reliability

Cronbach's alpha for the total score, self-promotion, non-display of imperfection, and nondisclosure of imperfection was 0.94, 0.90, 0.89, and 0.74, respectively, indicating the reasonable reliability of this scale.

4.6. Convergent and Divergent Validity

The divergent and convergent validity of the PSPS were assessed using SCS, TMPS, and DASS. As shown in Table 3, there is a positive and significant correlation between PSPS and its subscales (perfectionistic self-promotion, non-display of imperfection, and non-disclosure of imperfection) with TMPS and DASS (P < 0.05), indicating the convergent validity of the scale. Conversely, there is a negative and significant correlation between PSPS and its subscales with SCS (P < 0.05), indicating the divergent validity of the scale.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to measure the psychometric properties of the PSPS in an Iranian adult population. This is the first study to examine the statistical features of the Persian version of this scale, providing results that can enhance the intercultural applicability of the PSPS. Overall, the results of this study indicated that the Persian version of the PSPS is a reliable tool for evaluating the interpersonal expression of perfectionism.

The PSPS overall score and its subscales in the current research sample, based on Cronbach's alpha values and concurrent correlation coefficients, were consistent with previous research, confirming the reliability of the Persian version of this scale.

The significant correlation of scale items with three latent factors—perfectionistic self-promotion, non-display of imperfection, and non-disclosure of imperfection—confirms the existence of a three-factor model or three independent factors in this scale. Consistent with previous findings, significant and sufficient values for correlations and standardized factor loadings of all items, the loading of items on their related factors and scales according to the standardized coefficients, and the significance of T scores support the three-factor model.

The convergence between the three factors in the Persian version and other validated versions, including the Italian (20) and Portuguese (21) versions of PSPS, indicates that the three PSPS subscales should be considered separate but correlated variables. Thus, while the overall PSPS score may be used to assess perfectionist self-presentation, its three subscales can provide additional information, especially in specific aspects of this personality dimension. These results confirm the clinical and non-clinical applicability of this tool.

Consistent with previous research and the theoretical model underlying this scale, the correlation of the DASS, SCS, and TMPS scales with PSPS, particularly the positive and significant relationship between PSPS and its subscales with TMPS and DASS (P < 0.05), demonstrated the satisfactory convergent validity of the current version of this scale. DASS is among the components that are highly associated with TMPS and PSPS. According to the conceptualization of perfectionism by Hewitt et al. depression and perfectionism are connected via stress and perfectionism, which is one of the four ways that stress is involved in the relationship between depression and perfectionism (2). Perfectionists constantly put stress on themselves in pursuit of unrealistic goals. When they pressure themselves to meet these expectations, they experience significant anxiety, all due to this tendency (34). Individuals carefully evaluate themselves and others by focusing on the negative aspects of performance, which can lead to dissatisfaction and depression (35). There is evidence that perfectionistic self-presentation is a significant vulnerability factor for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and stress. This aspect of stress appears to exacerbate these symptoms, particularly in situations involving personal stress or failure. These findings align with evidence from Hewitt et al., who stated that rather than describing a trait dimension of perfectionism, this domain represents an individual’s “interpersonal expression” of their perfection. The authors hypothesized that perfectionistic self-presentation comprises three facets (25).

On the other hand, there was a significant negative relationship between PSPS and its subscales with the Self-Compassion Scale (P < 0.05), demonstrating the good divergent validity of the current version of PSPS. Self-compassion is negatively correlated with anxiety, depression (36), unstable self-worth, shame, and anger (37), and positively correlated with happiness, well-being, and adaptive coping strategies (38). These findings suggest that individuals who focus on their mistakes experience more pressure to be perfect and more fear of being rejected by others. Consequently, they are more likely to conceal their imperfections and shortcomings. The concept of self-compassion is widely acknowledged as a form of self-acceptance that influences both self-evaluation and the perception of others, providing numerous psychological benefits related to high self-esteem (39).

The results of this study are consistent with previous research that has shown PSPS correlates with HMPS and DASS (40). Perfectionist self-presentation has a positive correlation with trait dimensions of perfectionism (41). Several studies have also found that high levels of perfectionistic self-presentation are linked to a variety of adjustment issues, including depression, anxiety, and stress (42), as well as low levels of self-compassion (43). The divergence between the PSPS and SCS also indicated that the greater the self-compassion, the lower the scores reported on scales related to different styles of individual and interpersonal perfectionism.

These findings are consistent with the studies by Huang et al. (44) and Hewitt et al. (45). Perfectionistic self-presentation leads individuals to set high personal standards, which diminishes their self-esteem. As a result, individuals may fear the consequences of success, and this fear of success may trigger self-defeating, avoidance behaviors (46). These behaviors amplify dysfunctional attitudes, as such attitudes involve rigid, perfectionistic standards that the individual uses to judge themselves or others. As these attitudes are excessively rigid and resistant to change, they are considered dysfunctional (44). Thus, these attitudes may very well be linked to perfectionistic self-presentation. As a personality trait, perfectionistic self-presentation propels individuals to have high expectations, which, in turn, increases their dysfunctional attitudes and perfectionism.

Most of the findings of this study were in line with previous research. Non-display of imperfection involves denying an unwanted identity (such as being weak and imperfect) by hiding its weak or negative aspects (2). If the flaws and weaknesses of these individuals are not recognizable to others, they can maintain their complete and perfect image and avoid being identified as a person with defects and imperfections. People with extreme levels in this dimension see any situation in which it is necessary to do something in any way as a danger and find themselves vulnerable in such situations, predicting their experience of shame and humiliation.

Perfectionistic self-presentation represents a dynamic interpersonal style that directly reflects the drive to display one’s perfection or conceal one’s imperfection. Important distinctions in the self-presentation literature are made between “inclusionary” (attributive) and “exclusionary” (protective) self-presentation, and between “promotion” and “concealment.” There are two general motivational components in perfectionistic self-presentation. One involves striving to present one’s “perfections” by actively proclaiming them. The other involves striving to conceal any of one’s “imperfections” by neither displaying nor disclosing any flaws or shortcomings (47).

The strong need for approval that drives perfectionism is also likely to promote a defensive posture that protects the self from being known by others as imperfect. Unfortunately for perfectionistic self-presenters, this approach to life has severe psychosocial consequences. These individuals are regarded as unreachable and annoying and are not popular with others. People find it difficult to relate to them, and as a result, they find it difficult to establish any sort of intimate connection. This sets the stage for a form of social disconnection that Hewitt and Flett incorporated into a model of vulnerability to maladjustment and psychopathology (4).

5.1. Conclusions

According to the results of this study, the Persian version of the PSPS is a valid and reliable tool for measuring perfectionistic self-presentation in interpersonal relationships and can be used to identify the essence and consequences of perfectionistic self-presentation in adults. Furthermore, it allows psychologists and counselors to prevent the development of this personality trait. Overall, the Persian version of the PSPS appears to be a useful measure of the expression of perfection among Iranian adults and an important tool in understanding the nature and consequences of perfectionistic self-presentation in adults.

The current findings have important practical implications. Inclusion of the Persian version of the PSPS should enhance clinical assessments seeking to establish the nature of dysfunctional perfectionism in adults. The presented data help clarify the characteristics of perfectionistic self-presentation and their relationship with other clinically relevant concepts such as self-compassion, perfectionist traits, stress, anxiety, and depression. Future research on perfectionism needs to take these dimensions into consideration.

The results of the present study should be interpreted with caution due to some limitations we faced. First, the purpose of this tool was to investigate abnormal personality traits and was conducted in a sample of community-dwelling adults with a high level of education. In order to generalize the results to the broader community and other populations, it would have been better to include both clinical and non-clinical populations. Another limitation of the study was that only a single routine self-assessment method was used, rather than incorporating other data such as informed reports, interviews, and clinical evaluations.