1. Background

Play is children’s world and their primary occupation (1). Children learn, experience, and perceive the world through play (2). The play has different categories and definitions; however, almost all researchers agree on the free nature of play and the essential existence of joy (3). Play is crucial for children’s development in many areas, such as physical, emotional, language, social, and educational development (4-8). Although this definition highlights the importance of play in children’s lives, it also marginalizes the value of play itself. An approximately new definition of play is “play for the sake of play.” This definition emphasizes the essence of play for its value as the primary occupation of a child rather than its influences on children’s skills and learning (9, 10).

Play is an occupation that can be affected by some symptoms of different disorders. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has three main symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (11). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is the third most common mental disorder, with a prevalence of 3.4% in children and adolescents (12). In Iran, 4% of children and adolescents have ADHD (13). Children with ADHD have difficulties participating in their occupational areas, from activities of daily living (ADL) to play and leisure (14). Cordier has defined a model for the play of children with ADHD. This model emphasizes empathy, playing with peers, and motivation (15). A systematic review showed that there is always an emphasis on the social aspect of play in children with ADHD, while these children have significant cognitive problems (16). Based on LUDI play categories, the play has two primary dimensions: social and cognitive. The cognitive dimension has subcategories of practice play, symbolic play, constructive play, and play with rules (3). Symbolic play, also known as imaginary play, is well defined by Stagnitti as part of pretend play (17). Pretend play is when a child pretends anything, like being another person or pretending to be in another place or other situations (17).

Although there are several studies on social play in children with ADHD (18-20), we assumed that looking at the cognitive dimension of play is also crucial (16). We designed a protocol using participatory action research and intend to apply it to children with ADHD. Since it is a newly developed protocol, there is no evidence for this exact design. Generally, paying attention to the cognitive dimension of play in children with ADHD is also new. This protocol presents pretend play interventions to improve children’s play skills and participation. In other words, we aim to use play for the sake of play. This trial aims to assess the effect of the newly designed protocol on play skills and participation in children with ADHD.

2. Objectives

2.1. Primary Objective

The primary objective is to determine the effect of pretend play protocol on play skills and participation in children with ADHD.

2.2. Secondary Objective

As the study is designed to use play for the sake of play, no other secondary objective is defined.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The double-blinded clinical trial with parallel groups will be conducted with 6 - 8 children with ADHD as a pilot sample to show the effect size for the main study and using G-power software, the exact number of children will be determined. Children with ADHD will be divided into two main study designs: in-person and online. Trained occupational therapists will deliver the in-person intervention in the clinic, while children’s caregivers will deliver the online intervention. Caregivers will be provided with instructions every session, and the process will be checked and guided by the therapist, viewing the recorded videos. The whole protocol emerged from a participatory action research study. All participants continued the common care they received before the study. Occupational therapy with sensory-motor practices, cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy, and speech therapy are common forms. Also, any modifications made to the methods after the start of the trial will be disclosed with justifications. The study process is shown in Table 1.

| Study Phase | Screening | Intervention | Secondary Assessment | Follow-up | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turn of Visit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |||

| Conseco | * | ||||||||||||||||||

| Assessing eligibilities | * | ||||||||||||||||||

| Group interviews | * | * | |||||||||||||||||

| Conner’s test | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||||

| Participation test | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||||

| ChIPPA | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||||

| Demographic information | * | ||||||||||||||||||

The Protocol Process

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

Participants must have the following:

(1) A diagnosis of ADHD from a psychiatrist;

(2) A confirmed diagnosis of ADHD based on Conner’s test (scores higher than 34);

(3) Age of 4 - 6 years at the start of the trial;

(4) A plan to remain for the whole study time (2 months) and the follow-up (2 months after ending the intervention);

(5) Residence in Tehran;

(6) Good access to the internet for online sessions;

(7) Parents being able to read and write in Persian;

(8) Formal consent;

(9) Girls and boys are welcome to study.

The exclusion criteria include the following:

(1) Currently receiving a “play therapy” intervention;

(2) A major diagnosis other than ADHD, like autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, or other health conditions;

(3) Three absences or session cancellations without a reason

3.3. Recruitment Process

Participants will be recruited from the Iranian ADHD association, rehabilitation services, and through social media announcements on public and professional pages. Other clinicians and specialists can refer clients to this project, too. Centers should be in Tehran, and the research team would check medical history, including the ADHD diagnosis, in the participants’ profiles.

3.4. Participants’ Information

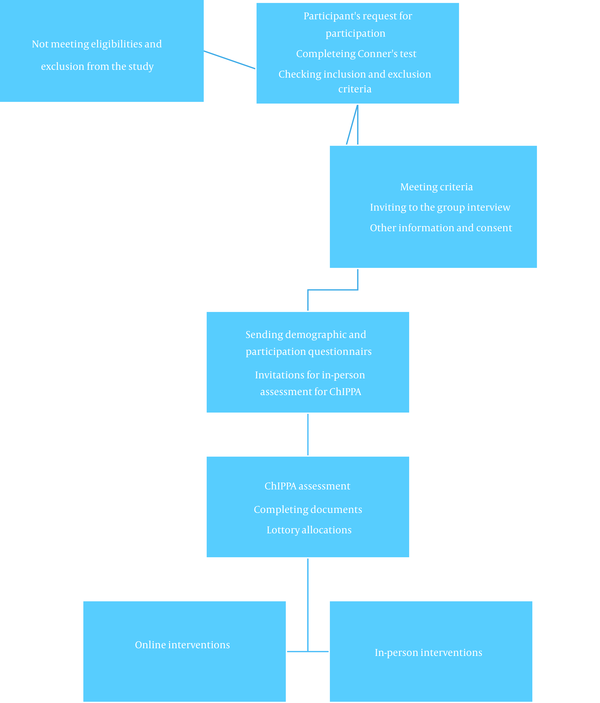

As the trial starts, a demographic questionnaire will be completed by participants. The information that we will probably receive is the age, gender, location of living, the status of education for the kids and their parents, having siblings, and the medical history as well as a general history of the child. The allocation guide is shown in Figure 1.

3.5. Informed Consent

A written paper is prepared to inform parents about the study process, potential benefits and harms, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. In addition to study information, it provides the researchers with the participants’ contact information. This consent is prepared in two copies, one for the participant and the other for the research team.

3.6. Randomization and Blinding

Participants will first get an identification number after claiming participation in the study. Based on the lottery, participants are placed in face-to-face or online intervention groups. This lottery will be done after baseline assessment, which comes after screening and informed consent. Half of the participants will be assigned to the online intervention, and the other half will get the in-person intervention, and the allocation ratio will be 1: 1. The list of each group will be kept in sealed envelopes until announcement time. The allocation sequence, enrolling participants, and assigning participants to interventions will be done by three research team members. Also, the assessor will be blind to the intervention process, and the trained therapists who deliver the intervention will stay blind to the test results. Different therapists will deliver online and in-person interventions, and the final reports will be written and analyzed by the first author of this manuscript, who will have no role in the interventional process. It is impossible to blind participants to the intervention they will receive.

3.7. Outcome Measures

3.7.1. Screening Measure

The first assessment used in the screening is Conner’s rating scale. This scale will be used before allocation, after the intervention, and at the follow-up stage. This scale is completed by parents and shows ADHD severity. We will encourage the same parent to complete the questionnaire at all stages (21).

3.7.2. Primary Outcome Measurement

The other primary outcome measurement is the “child-initiated pretend play assessment,” known as “ChIPPA,” which measures the child’s pretend play skills. This test looks like a play set; children engage with the play tools while the examiner observes them and gets codes and numbers for each behavior. This test will also be done during the baseline, after the intervention, and at the follow-up stage (22, 23). As ChIPPA is an observational test, an experienced occupational therapist with enough competency to work with ChIPPA will take all the tests.

3.7.3. Secondary Outcome Measurement

The “Child Participation Questionnaire (CPQ),” which has acceptable validity and reliability, will be used to assess the participation. It is not only limited to play participation but also assesses self-care, in-home participation, leisure activities, social participation, and educational environments. This questionnaire has 44 items and is completed by the parents of children aged 4 to 6 years (24).

3.8. Adherence

To ensure adherence, close monitoring of the child and getting parental reports for each session are predicted. Participatory research before the trial addresses and eases possible problems contributing to poor adherence. Moreover, since rehabilitation and occupational therapy are expensive in Iran and the treatment is free by well-known therapists in Tehran, the likelihood of adherence increases. Moreover, two different locations in the east and west of Tehran would be offered for in-person intervention for the sake of families that may have challenges in the heavy traffic of Tehran. In addition, a full occupational therapy evaluation is guaranteed for the follow-up session to encourage participants to participate. The rate of participants staying in the study up to the follow-up session will be reported.

3.9. Statistics

After finishing the follow-up, all the data are ready to be studied by a researcher blind to the whole process. Descriptive statistics will be used to define the characteristics of the participants. To compare the scores between baseline, after the intervention, and follow-up stages, first, the Shapiro-Wilks test will be used to see whether scores have a normal distribution. Then, Leven’s test will be applied for variance analysis. The data would be tested for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test; if they were normal, repeated-measures ANOVA would be applied to compare differences in scores through the intervention; if they did not have a normal distribution, the Friedman test is predicted. No subgroup analyses will be conducted.

3.10. In-person Interventions

In-person interventions emerged from a participatory action research study. The “Pretend Play Protocol” version one, named “PPP-1,” was designed in March 2022. This version will be applied to participants unless an updated version creates. The protocol has 16 sessions of 45 minutes delivered by a trained occupational therapist for eight weeks, twice a week. Triple P is a complete play protocol that consists of different play types with an emphasis on pretend play. Triple P is described in Table 2. At the beginning of sessions, parents will get some instruction emphasizing not talking about children’s problems and behavior during their attendance. Feedback is given and received via messengers through voice messages or texts. If parents have any complaints about their child, they should not talk about it when the child presents.

| Number of Visits | Content of Session | Warm-up (15 Minutes) | Session’s Description (25 Minutes) | Sum-up (5 Minutes) | Rules and Instructions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Free play | Greeting, asking general questions (what did you do today?/How do you do?); Doing perceptual-motor play. * This part can be skipped after the first session | The child can choose whatever he/she wants. Environment: Clinic; Available play items: Perceptual-motor tools (trampoline, tilt board, step, balance beam, ball pool, Hula hoops, G-ball, ball with different sizes); Pretend play tools: Structured tools (doll, animal figures, train, car, cooking tools, gun) and non-structured tools (shoe box, stone, wood sticks, towel); Plays with rules (Mench, snakes and stairs, snale, bowling, puzzles) a | The child helps in packing tools, and the therapist asks her/him: Did you like the play? Which one was your favorite?; And say goodbye. | The therapist will not direct the child and will play just if the child asks. If the child cannot stay in the room, the therapist can stop the free play process and perform day 2 of the protocol. |

| 2 | Perceptual motor play | The therapist suggests two perceptual-motor play to the child and asks him/her to choose one of them. After finishing the first play, two other options are suggested to the child, and this process continues to the end of the session. Some available suggestions: Playing with a ball, or trampoline, walking in a motor sequence using step and hula hoops | The therapist should design plays based on the child’s level and pay attention to the “just right challenge.” These plays should not be competitive, and the concept of win or should not be addressed. | ||

| 3 | Free play | Repeating the first-day protocol | |||

| 4 | Play with rules | The child can choose among three games: (Mench, snakes and stairs, and snale) a ; If a play ends and the child wants to change the game, two previous repetitive games can be suggested. | If the child has severe resistance, we will switch to perceptual-motor plays, but we set no rule in the first step, then set a simple rule for the motor task. Add rules in each step, and when the child cannot keep rules, we step back. | ||

| 5 | Pretend play | The child can choose between structured or non-structured play. In the first 15 minutes, the play has a freestyle, and then the therapist guides and continues one of the mentioned plays and starts stories by the child with more narrations. | If the child cannot continue to play for 15 minutes, the therapist can start the intervention sooner. The therapist’s narration should be incomplete, and the child should have time to complete the story. | ||

| 6 | The therapist starts to play with a theme that is not reported by parents as a problem for the child (for example, if the child is scared of doctors), the therapist will not start to play with the doctor’s role. The therapist does not play a role directly, but dolls play roles. Scenarios have a simple challenge that is neutral for the child (for example, this doll is sick but does not go to the doctor). The scenario continues, and if the child changes the whole story in another scenario, the therapist will not resist. | ||||

| 7 | The therapist introduces three scenarios, and the child chooses one. These scenarios are based on a child’s problems. | ||||

| 8 | A child’s only choice is choosing among different unstructured play materials. After choosing the play materials for the child, three themes are suggested to the child for playing: (1) Constructing a city; (2) playing a story of a family who is going to the party; and (3) the child’s scenario. | ||||

| 9 | Social play with dolls | When the child entered the room, five dolls were around a table (step) drinking tea. The therapist does not emphasize any of these dolls, and the child chooses her/his own choice. After the child chooses the doll, roles will be assigned. These roles are based on the child’s main challenges. | |||

| 10 | Empathy with dolls | Dolls hidden on the therapist’s back will come out one by one and talk to the child about their feelings and the story behind these emotions. Happy, sad, angry, shy, and scared dolls are suggested. If the child does not know how to behave with the doll, the other doll will come and show the correct way of empathy. At the end of the session, the therapist will play a role and ask the child for empathy. | |||

| 11 | Play with the parent | The parent is invited to enter the therapy room. The therapist stays quiet and watches the parent-child interactions, and writes feedback. The therapist may guide the play using the stories from 10 previous sessions if the direction is needed. | |||

| 12 | Thematic play with a focus on the individual’s problems | The therapist starts to play with a theme that parents do not report as a problem for the child (for example, if the child is scared of doctors), the therapist will not start to play with the doctor’s role. The therapist does not play a role directly, but dolls play the roles. Scenarios have a simple challenge that is neutral for the child (for example, this doll is sick but does not go to the doctor). The scenario continues, and if the child changes the whole story in another scenario, the therapist will not resist. | |||

| 13 | Play with a peer | Two children from the study will be grouped together. If the child has siblings, it is possible to group the child with them. Three plays are suggested in the session: (1) A play that is not the children’s favorite but has enough sources for both of the children; (2) a play that is the child favorite but has to share resources; and (3) an agreed play by both of children. If challenges happen, the therapist will react and help the child to learn how to solve such problems. This will be symbolic by using dolls. | |||

| 14 | Group play | Play is done in a group of more than three children. The therapist will not play the lead role and will observe children’s interactions and writes challenges. If the play does not shape without therapist intervention, is aggressive, or has other difficulties, the therapist will suggest two plays that the team has to agree on one. If the agreement is not made, the therapist may try to facilitate it, and if it does not work, the therapist will start leadership. | |||

| 15 | Free play | The first session is repeated with writing the residual problems that the child has. |

In-person Protocol

3.11. Online Intervention

The online intervention will have the same protocol but will be delivered by parents. Each protocol session is instructed in one session through a video call on the parent’s preferred platform. Parents are asked to record the session and send it to the therapist. Recorded videos will be analyzed, and feedback will be made on parents’ performance. During the therapeutic sessions, the therapist is available to answer any possible questions. The whole written interventional package delivered in the in-person sessions will be described in detail for parents session by session during the video call. For the 11 sessions, parents will be asked to record a free play session with their kids, and the therapist will check that video during a call or offline. Every session will consist of an educational component in which the therapist informs parents about the material to be covered at the next session, a clarifying part in which the therapist clarifies any unclear topic for parents, and a summary part in which the parents will be asked to repeat the plan of intervention in detail to assure the therapist that they have understood what they need to do. The therapist would also be available to answer related questions via email and phone between sessions.

3.12. Fidelity of the Study

The therapists will be trained during a two-day workshop to ensure the protocol is correctly applied. They should have at least a bachelor’s degree in occupational therapy and two years of experience working with children with ADHD. The therapist also needs an inner drive for play and an intention to learn new methods playfully. The first five children’s sessions will be recorded, or the other therapist will watch the session using the one-way mirror room if applicable.

4. Results

The statistics will show the differences in play skills and participation scores before and after the study, indicating the designed protocol’s efficacy. Additionally, follow-up findings will show whether the results are maintained. After getting the results, a judgment could be made about the protocol’s efficacy, and some suggestions may emerge to improve its quality. According to the results, a suggestion for starting workshops and encouraging other therapists would be made, and knowledge translations would be scheduled.

For showing results, a table will be embedded in the results demonstrating the demographic characteristics of patients. A graph will also be used to show the participants’ recruitment process. In order to show the differences in the scores during the time, three tables for ChIPPA, CPQ, and ICPAS are predicted. A sample of the predicted table is brought in Table 3. This table shows the changes in the most important variable of the ChIPPA, which shows the elaboration of children’s play. The table will be filled after the study, and similar tables for other tests and variables are planned that may merge into a single table to reduce the number of tables.

| Variables | Power | Effect Size | P-Value | Before the Intervention | After the Intervention | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Standard Deviation | Medium | Standard Deviation | Medium | Standard Deviation | ||||

| Conventional PEPA a | |||||||||

| Symbolic PEPA | |||||||||

| Combined PEPA | |||||||||

Comparing the changes in Child-initiated Pretend Play Assessment variables

5. Conclusions

The designed protocol aims to improve the play skills and participation of children with ADHD. After this study, a bright and detailed protocol in 16 sessions would be available to be taught to occupational therapists with the support of evidence that is hypothesized to be efficient. As the resources of protocols for working with children with ADHD are critically limited, a session-by-session detailed protocol would be helpful in clinical practice and research.