1. Context

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious illness caused by a new strain of coronavirus (1). On January 2020, the World Health Organization notified that the spread caused a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) (2). The data related to the coronavirus led to some strict and unprecedented preventive measures (3). These methods contributed significantly to reducing the spread of the virus and increasing socioeconomic instability, global despair, and negative consequences on the mental and sexual health of societies (4, 5). Since biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, and legal factors affect sexual function (6), COVID-19 might adversely affect female sexual function due to the fear of contagion, stressful conditions, and changes in daily life (5). Sexual health is a chief sector of women’s standard of lifetime (7) and is necessary for the overall health and well-being of individuals, couples, and families. Satisfactory sexual activity also enhances physical health and overall quality of life (4). On the other hand, female sexual dysfunction (FSD) results in anxiety, depression, communication breakdown, and disruption in interpersonal relationships (8). Female sexual dysfunction is defined as an ongoing or frequent disorder of sexual interest/desire, mental and genital arousal disorders, orgasm disorders, and/or sexual pain and discomfort (9). The strong relationship between sexual dysfunction and quality of life disorders has made it an important public health concern (10), with a significant economic burden on the health system of societies (11).

Given the impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on sexual health on the one hand and the adverse effects of FSD on the family and society on the other hand, the awareness of the healthcare staff regarding the prevalence of this problem and influential factors can enable the healthcare team to take appropriate preventive or mitigation measures. So far, limited review studies have been conducted regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s sexual function.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s sexual function.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Search Strategy

The population of the current systematic review study included all observational studies on female sexual function throughout the COVID-19 quarantine. Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases were searched with no language limitations. Two independent researchers reviewed all relevant articles published until November 30, 2021. Searching in databases was performed using English keywords. The search keywords were selected based on the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) system and included “sexual function”, “sexual dysfunction”, “sexual health”, “sexual activity”, “sexual activities”, “sexual behavior”, “sex behavior”, and “COVID-19”, combined with AND/OR Boolean operators.

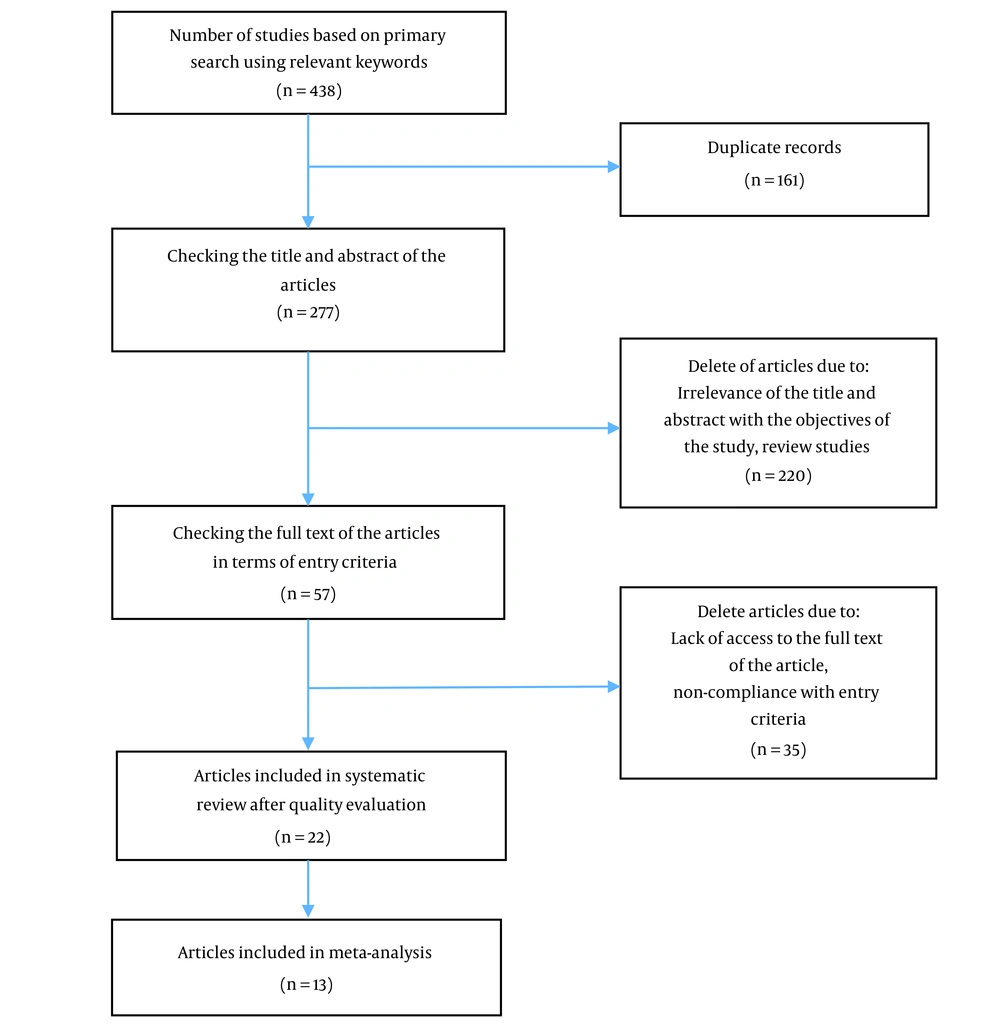

The search in the above-mentioned databases resulted in retrieving 438 articles, which were then entered into the Endnote software (version X9). Using Endnote software, 161 duplicate articles were identified and removed, after which the headlines and abstracts of 277 papers were examined. Then, 57 papers were selected for full-text investigation according to the objectives of the present study, all of which were published in English. When the full text of an article was not available, contact was made with the corresponding author to have access to the full file of the article. However, the full texts of two articles were not available, and 33 more papers did not comply with the inclusion criteria, leading to their exclusion. Finally, 22 articles were included in the study, the quality of which was evaluated by two independent authors (E.Z and A.Z) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for quality assessment adapted by Herzog et al. for cross-sectional studies (12). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies consists of seven items and three domains, namely selection of participants (items 1 - 4), comparisons (item 5), and results and statistics (items 6 and 7). The scores vary from 0 to 10, where 9 - 10, 7 - 8, 5 - 6, and 0 - 4 mean very good, good, satisfactory, and unsatisfactory, respectively (13). A consensus approach was used to determine the quality score for each study. Figure 1 shows the selection process of the articles.

3.2. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria included cross-sectional observational, cohort, and control-case published articles, with a research unit of women who had no history of mental illnesses, chronic systemic diseases, and urogenital diseases and did not take neuropsychiatric or any other drugs affecting sexual function. Articles whose research unit was women with COVID-19, those with no availability of the full text, qualitative research, reviews, abstracts, letters to the editor, and clinical trials were excluded from the study.

The information was extracted using a researcher-made form, which included the data, such as author’s name, year of publication, place of research, number of samples, participants’ characteristics (e.g., demographics and age), data collection tools, findings, and the results of evaluating the quality status of the articles.

3.3. Assessment of the Quality Status of Articles

The quality status of all studies was evaluated using the NOS (12). Based on the NOS checklist, 6, 11, and 5 articles received scores of 9 - 10 (very good), 7 - 8 (good), and 5 - 6 (satisfactory), respectively. It is noteworthy that none of the studies received scores of 0 - 4 (unsatisfactory). All the studies receiving scores of ≥ 5 were entered into the research (Table 1).

| Study (First Author) | Selection | Comparability According to Method and Analysis | Outcome | Total Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the Sample | Sample Size | Non-respondents | Ascertainment of Exposure | Assessment of Outcome | Statistical Test | |||

| Ilgen et al. (14) | + | ++ | ++ | + | 6 | |||

| Küçükyildiz et al. (15) | + | ++ | ++ | + | 6 | |||

| Mirzaei et al. (16) | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 9 |

| Yuksel and Ozgor (17) | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 9 |

| Karagöz et al. (18) | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 8 | |

| Mohammadi et al. (19) | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 8 | |

| Karakas et al. (20) | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 8 | |

| Costantini et al. (21) | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 7 | ||

| Sotiropoulou et al. (22) | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 7 | ||

| Carvalho et al. (23) | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 9 |

| Effati-Daryani et al. (24) | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 9 |

| Mollaioli et al. (25) | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 9 |

| Karsiyakali et al. (26) | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 8 | |

| Bhambhvani et al. (27) | + | ++ | ++ | + | 6 | |||

| Hidalgo and Dewitte (28) | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 7 | ||

| Schiavi et al. (5) | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 8 | |

| Szuster et al. (29) | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 8 | |

| Omar et al. (30) | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 9 |

| Dong et al. (31) | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 7 | ||

| Culha et al. (32) | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | 7 | ||

| Fuchs et al. (33) | + | ++ | ++ | + | 6 | |||

| Denizli et al. (34) | + | ++ | + | + | 5 | |||

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The current study used the effect size to interpret and analyze the results. The random effects model was used for data heterogeneity. A Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were also used to check the potential bias of publication.

4. Results

The current study reviewed all published articles in electronic databases matching the research objectives. In the first step, 438 articles (Google Scholar = 236; Web of Science = 41; Scopus = 87; ScienceDirect = 22; PubMed = 52) were extracted through primary search using relevant keywords. The removal of duplicate articles and review of the titles, abstracts, and then the full text of the remaining articles resulted in 22 final articles with a total sample size of 12,409 for assessment (Figure 1). All the included studies were cross-sectional except for 1 longitudinal study and 1 case-control study. These studies were conducted in 10 different countries, namely Turkey (n = 8), Iran (n = 3), Italy (n = 3), Poland (n = 2), Greece (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), America (n = 1), Ecuador (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), and China (n = 1). Based on the NOS checklist, all the studies were of high quality. The female sexual function index (FSFI) was used in 21 studies to evaluate women’s sexual performance. However, one study used the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX) (34). Table 2 shows the specification of the studies that comprised the current systematic review.

| Study | Author Time Location | Method | Size of the Sample | (Mean/range) of Age (y) | Assessment Tool | Results | Influential Factors in Female Sexual Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Female sexual function and COVID-19 pandemic (14) | Ilgen et al. 2021 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 99 | 35.1 ± 5.8 | 1. FSFI 2. BAI 3. BDI | The FSFI scores showed a high status of dysfunction even before the pandemic. Findings did not show differences before and after (21.8 vs. 21.0, P = 0.27). High levels of anxiety and depression were observed in the study (11.2 vs. 13.3, P < 0.01; 10.0 vs. 13.7, P < 0.01, respectively). The pandemic did not affect female sexual status. However, anxiety and depression were associated with the pandemic. | Negative factors: Anxiety |

| 2. A hospital-based, prospective, cross-sectional comparative study of sexual dysfunction of women throughout COVID-19 (15) | Küçükyildiz et al. 2021 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 150 50 pregnant women 50 healthcare women 50 other women | 18 - 53 | FSFI | The median FSFI score was obtained at 23.50, and 68.7% of women were diagnosed with sexual dysfunction. Group 2 had a significantly elevated FSFI score (P = 0.001) and higher FSFI score in the areas of orgasm, arousal, lubrication, and pain than the rest. | Negative factors: Unemployment, Lack of university education, Sexual pain was higher in women who had a normal vaginal delivery. |

| 3. Mental health, quality of life, and sexual function under strain of COVID‑19 Pandemic in Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study (16) | Mirzaei et al. 2021 Iran | Cross-sectional | 604 200 pregnant women 203 lactating women 201 normal women | 20.81 ± 5.92 | 1. HADS 2. FSFI 3. Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) | Anxiety and depression scores in pregnant and lactating women were higher than normal group (P < 0.001). In addition, the score of QOL (Quality of life) and FSFI in pregnant and lactating women were lower than in normal women (P < 0.001). | Negative factors: Pregnancy, Lactation |

| 4. Female sexual action under the COVID-19 pandemic (17) | Yuksel and Ozgor, 2020 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 58 | 27.6 ± 4.4 | 1. FSFI 2. A researcher-designed questionnaire | The mean of sexual intercourse repetition increased throughout the pandemic in comparison to 6-12 last months (2.4 vs. 1.9, P = 0.001). The FSFI scores were better before the pandemic than during the pandemic (20.52 vs. 17.56, P = 0.001). | - |

| 5. A cross-sectional study among couples in Turkey: COVID-19 influences on sexuality (18) | Karagöz et al. 2020 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 97 women and 148 men | 34.7 ± 6.67 | 1. FFSFI 2. IIEF 3. GAD-7 4. PHQ-9 5. PSS | The FSFI scores were lower in males and females throughout the pandemic than before (P = 0.001 and P = 0.027, respectively). Throughout the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period, the repetition of sexual relationships dropped in males (P = 0.001) and females (P = 0.001); however, sexual prevention and solitary sexual approach action (e.g., masturbation or exposure to sexual videos) were elevated in males (P = 0.001) and females (P = 0.022). | Negative factors: Older age Anxiety, depression, stress perception positive factors: Spending more time with a partner |

| 6. Sexual dysfunction prevalence and related factors in iranian pregnant women throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic (19) | Mohammadi et al. 2021 Iran | Cross-sectional | 205 pregnant women | 29.3 ± 5.5 | FSFI | The FSFI mean (SD) of the overall score was 21.54 (8.37), and 80% of participants suffered from sexual dysfunction. | Negative factors: Husband over 35 years, living in private homes compared to living in parents’ homes, moderate marital satisfaction compared to high or extremely high marital satisfaction, husband blue-collar workers compared to husband white-collar workers |

| 7. Assessment of the risk factors of sexual dysfunction in pregnant women throughout COVID-19 (20) | Karakas et al. 2021 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 180 135 pregnant women 45 non-pregnant women | 20-40 | FSFI | The FSFI scores were significantly lower in pregnant women (P = 0.002). Healthy pregnant women showed decreased levels of sexual function due to quarantine measures throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. | Negative factors: Having university degree, multiparity, pregnancy, unplanned, pregnancy |

| 8. Lockdown impact on couples’ sex lives (21) | Costantini et al. 2021 Italy | Cross-sectional | 1112 women and 1037 men | 43 ± 12.5 | 1. FSFI 2. IIEF-15 3. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM) 4. Marital adjustment test (MAT) | A 49% increase was diagnosed in the sex lives of participants, particularly roommates; for 29%, it deteriorated; however, for 22% of participants, it did not change. Women with declined sex lives actually had no sexual dysfunction; nevertheless, they had tension, anxiety, fear, and insomnia. | Negative factors: Anxiety, tension, fear, insomnia, being unemployed or smart working, having sons |

| 9. COVID-19 social separation measures in sexual function and relationship quality of Greek Couples (22) | Sotiropoulou et al. 2021 Greece | Cross-sectional | 213 women and 86 men | 18 years and older | 1. FSFI 2. IIEF 3. Sexual activity 4. Relationship quality 5. Mood and anxiety | Minor or no harmful effects were detected regarding sexual function. Those who have no access to their partner were observed with upraised anxiety and deficient temper. Being in a steady relationship and living with their partner, but only for couples without children, resulted in satisfaction through sexual activity and enhanced emotional security. Quarantine and distant socializing had no effect on sexual function and relationship quality. | Negative factors: Anxiety |

| 10. Link between COVID-19 restriction, psychological settlement and sexual functioning in a sample of portuguese men and women (23) | Carvalho et al. 2021 Portugal | Cross-sectional | 417 women and 245 men | 34.3 ± 10.97 | 1. FSFI 2. IIEF 3. Psychological adjustment | Although limitation measures were not directly related to most sexual functioning areas, psychological adjustment throughout the lockdown predicted lower sexual functioning in both genders. | Negative factors: Increasing psychological adjustment |

| 11. Relation between mental health and sexual function in pregnant women throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iran (24) | Effati-Daryani et al. 2021 Iran | Cross-sectional | 437 pregnant women | 29.7 ± 5.5 | 1. FSFI 2. DASS | The mean (SD) of FSFI was 20.0 (8.50) from the accessible range of 2-36. The mean (SD) of depression, stress, and anxiety scale was 4.81 (5.22), 5.13 (4.37), and 7.86 (4.50) (possible score range: 0-21), respectively. | Negative factors: Stress, anxiety, depression, positive factors: Benign stress type of spouse’s job, sufficient household income, living with parents, higher marital satisfaction, increase in gestational age |

| 12. Sexual activity advantages on psychological, relational, and sexual health throughout the COVID-19 Breakout (25) | Mollaioli et al. 2021 Italy | Case-control | 4177 women and 2644 men | 32.83 ± 11.24 | 1. FSFI 2. IIEF 3. GAD-7 for anxiety 4. PHQ-9 5 DAS for quality of relationships 6. Male-female versions of the Orgasmometer | Sexually active individuals showed low scores of anxieties and depression throughout lockdown. However, sexual activity, gender, and living alone throughout lockdown significantly affected anxiety and depression grades (P < .0001). No sexual activity throughout lockdown was linked to more danger of developing anxiety and depression (P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001, respectively). | Negative factors: Older age (for sexual desire and pain) |

| 13. An internet-based nationwide survey study: Evaluation of individuals’ sexual functioning living in Turkey Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (26) | Karsiyakali et al. Turkey | Cross-sectional | 685 women and 671 men | 33.16 ± 8.31 | Questions for evaluation of the sexual intercourse repetition and sexual desire based on FSFI and IIEF | Sexual intercourse mean number before COVID-19 was 1.86 ± 1.67 per week; however, this value declined to 1.35 ± 2.04 throughout the COVID-19 crisis. There was a significant decrease in the number of weekly intercourses when they were compared in terms of using alcohol and smoking, marital and parental status, working as a healthcare worker, having a stable sexual partner, and job status throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (P < 0.05, for each). | Negative factors (for sexual desire): Older age, female gender, smoking cigarette, being single, not having a child, being jobless, stable partnership |

| 14. COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and its impact on female sexual function (27) | Bhambhvani et al. 2021 United States | Longitudinal | 91 | 43.1 ± 11.8 | 1. FSFI 2. Sexual repetition 3. PHQ-4 | Generally, a reduction in FSFI scores was shown throughout the pandemic (27.2 vs. 28.8, P = 0.002), especially in lubrication (4.90 vs. 5.22, P = 0.004), arousal (4.41 vs. 4.86, P = 0.0002), and satisfaction (4.40 vs. 4.70, P = 0.04). Sexual repetition did not change. The risk for female sexual dysfunction significantly increased throughout the pandemic (P = 0.002). | Negative factors: Anxiety, depression |

| 15. Relational, sociocultural, and individual determinants of sexual satisfaction and function in Ecuador (28) | Hidalgo and Dewitte, 2021 Ecuador | Cross-sectional | 431 women and 159 men | 18-58 | 1. Brief Sexual Opinion Survey 2. Sexual Double Standards Scale 3 SDBQ 4. New Sexual Satisfaction Scale 5. FSFI 6. IIEF 7. Couples satisfaction Index (15) | The quarantine effect showed no significant association with sexual function and satisfaction. Only female sexual satisfaction was affected by the perceived effect of quarantine. Mainly in women, markers of sexual conservatism were related inversely to sexual function and satisfaction. | Negative factors: Higher score of sexual dysfunction beliefs positive factors: higher sexual double standards, higher sexual satisfaction, higher relationship satisfaction |

| 16. Love in COVID-19 Crisis: Quality of life and sexual function analysis throughout the social distancing measures in a group of Italian reproductive-age women (5) | Schiavi et al. 2020 Italy | Cross-sectional | 89 | 28-50 | 1. FSFI 2. FSDS 3. SF-36 for the quality-of-life assessment | Mean sexual intercourse/month dropped from 6.3 ± 1.9 to 2.3 ± 1.8, mean difference: -3.9 ± 1.2. The FSFI reduced significantly (29.2 ± 4.2 vs. 19.2 ± 3.3, mean difference: -9.7 ± 2.6), and FSDS increased significantly (9.3 ± 5.5 vs. 20.1 ± 5.2, mean difference: 10.8 ± 3.4). | Negative factors: Working outside the home, university educational level parity ≥ 1 |

| 17. An online survey: Polish women’s mental and sexual health throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (29) | Szuster et al. 2021 Poland | Cross-sectional | 1644 | 25.11 ± 7.09 | 1. BDI 2. FSFI | Lower repetition of sexual activity was reported (P < 0.001) and lower libido level (P < 0.001) throughout the pandemic than in the past. The FSFI and BDI scores were significantly correlated (P < 0.001). | Negative factors: Depression, presence of any comorbid chronic disease, fear of infection, health anxiety, perceived loneliness, news listening |

| 18. Are women suffering more? psychological and sexual health throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic in Egypt (30) | Omar et al. 2021 Egypt | Cross-sectional | 479 women and 217 men | Not mentioned | 1. GAD-7 2. PHQ-9 3. FSFI 4. IIEF-5 5. Index of sexual satisfaction (ISS) | Sexual satisfaction was (91.2%, 73.5%) which decreased throughout lockdown (70.5%, 56.2%) in men and women, respectively. More males (70.5%) reported being satisfied with their sexual performance than females throughout lockdown (56.2%) (P < 0.001). Females reported more sexual stress (70.8%) than males (63.1%). | Negative factors (for sexual stress): Being jobless husband’s age over 35 years 5-10 years of marriage anxiety |

| 19. Sexual and psychological health of couples with azoospermia in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (31) | Dong et al. 2021 China | Cross-sectional | 200 couples (100 azoospermia and 100 normal) | 32.76 ± 4.32 in the wives of patients with azoospermia and 33.51 ± 4.42 in the wives of patients with normozoospermia | 1. FSFI 2. IIEF-15 3. Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (PEDT) 4. A researcher-designed questionnaire 5. GAD-7 6. PHQ-9 | Total FSFI scores (25.12 ± 5.56 vs. 26.75 ± 4.82, t = -2:22, P = 0.03) of wives of men with azoospermia were lower than normal couples. | Negative factors: Anxiety, depression |

| 20. Healthcare sexual attitudes throughout the COVID-19 outbreak (32) | Culha et al. 2021 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 89 women and 96 men | 30.65 ± 5.99 | 1. FSFI 2. State Anxiety Inventory (STAI-1 and 2) 4. BDI | Sexual desire of healthcare workers (3.49 ± 1.12 vs. 3.22 ± 1.17; P = 0.003), weekly sexual intercourse/masturbation number (2.53 ± 1.12 vs. 1.32 ± 1.27; P < 0.001), foreplay time (16.38 ± 12.35 vs. 12.02 ± 12.14; P < 0.001), and sexual intercourse time (24.65 ± 19.58 vs. 19.38 ± 18.85; P < 0.001) diminished, compared to the pre-COVID-19 crisis. | Negative factors: Male gender, alcohol consumption |

| 21. COVID-19 impacts on female sexual health (33) | Fuchs et al. 2021 Poland | Cross-sectional | 764 | 25.1 ± 4.3 | FSFI | The FSFI score was 30.1 ± 4.4 before the crisis and changed to 25.8 ± 9.7 throughout it. All domain scores also diminished (P < 0.001). | Negative factors: Stress, misunderstandings with partner, fear of COVID-19, lower education, bad living conditions, unemployment, living with their parents |

| 22. Depression and sexual function in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are pregnant women affected more negatively? (34) | Denizli et al. 2021 Turkey | Cross-sectional | 188 96 pregnant women and 92 non-pregnant women | 30.1 ± 6.4 | 1. BDI 2. ASEX | The depression status was the same in both groups (P = 0.846). Pregnant women (P < 0.001) showed a higher sexual dysfunction rate than non-pregnant women. | Negative factors: A lower level of schooling, less income, loss of income in the course of the pandemic, pregnancy |

Abbreviations: FSFI, female sexual function index; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; ASEX, Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale; DASS, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; GAD-7, 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder; SD, standard deviation; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IIEF, international index of erectile function; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; IIEF-15, international index of erectile function-15; DAS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale; SDBQ, Sexual Dysfunctional Beliefs Questionnaire; FSDS, Female Sexual Distress Scale.

4.1. Consequences of COVID-19 on Female Sexual Function

Nine studies showed the prevalence of sexual dysfunction throughout the epidemic (Table 2), ranging from 17.6% in Greece to 87.4% in Turkish pregnant women. Six studies reported female sexual function scores before and throughout the COVID-19 period. In studies by Bhambhvani (No. 14), Schiavi (No. 16), and Fuchs (No. 21), the before and after evaluations were used on the same samples. In studies by Ilgen (35) and Yuksel and Ozgor (No. 4), the data from a previous study that was conducted for another purpose was used, and healthy individuals or the control group of these studies were invited to participate in the new study. In Karagöz’s study (No. 5), participants were asked to complete questionnaires based on their past experiences before the epidemic the first time and to respond to questionnaires based on their experiences during the epidemic the second time. All of these 6 studies revealed a drop in the mean FSFI scores throughout the pandemic, contrasting with before the crisis. The findings were statistically significant in 5 studies (5, 17, 18, 27, 33) and insignificant in 1 study (14). Eight studies investigated the alternation of sexual activity throughout the COVID-19 epidemic, the majority of which (n = 6) reported a decline in the repetition of sexual activity compared to before the COVID-19 outbreak (5, 18, 26, 29, 32, 33). On the other hand, 1 study reported an increase in the mean repetition of sexual activity in Turkish women (2.4 vs. 1.9, P = 0.001) (17). However, another study in America reported no changes in the repetition of sexual activity (27). One of the studies conducted on healthcare workers in Turkey reported a drop in the repetition of weekly sexual activity (P < 0.001) and sexual desire (P = 0.003) of the participants throughout the epidemic (32).

4.2. Influential Factors in Female Sexual Function Throughout the COVID-19 Epidemic

Relied on the observations of the present studies, various items can affect female sexual function throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). The main risk factors for reducing female sexual function mentioned in the studies were anxiety (n = 8), depression (n = 5), unemployment or variable employment status (n = 5), lower level of income or economic status (n = 3), older age (n = 3), and fear (n = 3). The education level was examined in 5 studies, 3 of which reported a relationship between a lower level of education and lower scores of sexual function (15, 33, 34); nevertheless, 2 articles reported such a relationship for university education (5, 20). Multiparity and pregnancy were associated with less female sexual function in 2 (5, 20) and 3 (16, 20, 34) studies, respectively. Research conducted on pregnant women in Iran also showed that higher gestational age was associated with a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction (24). In Turkey, healthcare staff reported better sexual function scores throughout the COVID-19 crisis than pregnant and other women (P = 0.001) (15). A study conducted on 200 Chinese couples showed that the overall score of sexual function was lower in the women with azoospermia husbands than the women with normal husbands (25.12 ± 5.56 vs. 26.75 ± 4.82, t = - 2.22, P = 0.03) (31). Three studies also mentioned factors that positively affected female sexual function throughout the crisis, including spending more time with their spouses (18), higher sexual double standard (SDS), sexual and relationship satisfaction (28), mild stress, the type of spouse’s occupation, living with the parents, higher marital contentment, and higher gestational age (24).

4.3. Meta-analysis

4.3.1. Sexual Desire

The mean sexual desire scores were 3.91 and 3.62 using the fixed (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.88 - 3.94) and random (95% CI: 3.38 - 3.86) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 273.915, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

A Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to check the potential bias of publication in all domains. The results of the test confirmed the bias of publication (t = 3.08, P = 0.01) and the significant slope of the line (t = 26.82, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the results of which did not change, which can indicate that none of the studies had a high bias.

4.3.2. Arousal

The mean arousal scores were 4.27 and 3.67 using the fixed (95% CI: 4.23 - 4.03) and random (95% CI: 3.30 - 4.04) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 998.896, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

The results of the test confirmed the bias of publication (t = 4.68, P = 0.001) and the significant slope of the line (t = 26.56, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the results of which did not change, which can indicate that none of the studies had a high bias.

4.3.3. Lubrication

The mean lubrication scores were 4.86 and 4.19 using the fixed (95% CI: 4.82 - 4.89) and random (95% CI: 3.83 - 4.56) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 895.711, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

The results of the test confirmed the bias of publication (t = 4.55, P = 0.001) and the significant slope of the line (t = 34.11, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the results of which were 4.231 (4.202 - 4.261) and 4.098 (3.495 - 4.701) with fixed and random methods, respectively.

4.3.4. Orgasm

The mean orgasm scores were 4.26 and 3.89 using the fixed (95% CI: 4.22 - 4.30) and random (95% CI: 3.53 - 4.25) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 766.076, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

The results of the test confirmed the bias of publication (t = 2.38, P = 0.036) and the significant slope of the line (t = 18.10, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the results of which were 3.617 (3.586 - 3.649) and 3.608 (3.138 - 4.077) with fixed and random methods, respectively.

4.4. Satisfaction

The mean satisfaction scores were 4.43 and 4.04 using the fixed (95% CI: 3.39 - 4.47) and random (95% CI: 3.78 - 4.30) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 478.350, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

The results of the test confirmed the bias of publication (t = 3.23, P = 0.008) and the significant slope of the line (t = 29.50, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the results of which were 4.016 (3.985 - 4.046) and 3.908 (3.527 - 4.290) with fixed and random methods, respectively.

4.4.1. Pain

The mean pain scores were 4.70 and 4.18 using the fixed (95% CI: 4.67 - 4.74) and random (95% CI: 3.65 - 4.72) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 2031.31, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

The findings showed no bias in publication (t = 2.04, P = 0.066) but a significant slope of the line (t = 14.88, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the results of which were 4.085 (4.056 - 4.114) and 4.087 (3.421 - 4.754) with fixed and random methods, respectively.

4.4.2. Overall Score of the Female Sexual Function Index

The mean FSFI scores were 25.36 and 23.34 using the fixed (95% CI: 25.20 - 25.52) and random (95% CI: 21.17 - 25.52) methods, respectively. Considering the data heterogeneity in Cochran’s Q test (Q = 2391.20, P < 0.001), the random method provided more accurate estimations.

The results of the Egger’s test showed no bias of publication (t = 2.18, P = 0.048) but a significant slope of the line (t = 15.96, P < 0.001). Therefore, the Trim and Fill analysis was used for estimations, the outcomes of which did not change, which can indicate that none of the studies had a high bias.

5. Discussion

Since sexual function is significantly influenced by stress, anxiety, and depression, all of which are intensified through epidemics, the COVID-19 epidemic can also affect individuals’ sexual function and life (24). Sexual activity affects immune response, mental health, and cognitive function positively and can reduce psychosocial stress (4). The present study investigated the female sexual function and the influential factors in it throughout the COVID-19 crisis. The FSFI was used as the golden standard to measure women’s sexual activity (36). This tool has 19 items scored on a Likert scale from 0 (or 1) to 5. The FSFI consists of six subscales, with the utmost score of 6 for each area and 36 for the total scale. Higher scores indicate better sexual functioning, and an overall score of 26.0 has been validated as the cut-off point for diagnosis with FSD (37). In the current study, the mean FSFI score throughout the epidemic was 23.34 using the random effects method. Additionally, the scores of sexual tendency, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain were 3.62, 3.67, 4.19, 3.89, 4.04, and 4.18, respectively, using the random effects method.

Out of the 6 studies that reported the FSFI scores before and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, 5 studies indicated a statistically significant drop in the mean scores of female sexual function throughout the epidemic, compared to before the epidemic (5, 17, 27, 33, 35). Most studies comparing the repetition of sexual activity before and during the COVID-19 crisis reported a decrease in the repetition of sexual activity throughout the crisis (5, 14, 17, 27, 29, 32). However, a study in Turkey reported an increase in the repetition of sexual activity, which could be attributed to spending more time at home (17). The COVID-19 epidemic can have different impacts on female sexual function worldwide because quarantine and mental stress can aggravate sexual disorders, such as hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), on the one hand, while increasing the intimacy of couples due to spending more time at home on the other hand (4). In addition, stress is a factor that can be associated with both increased sexual activity and decreased sexual desire. The findings of a study conducted on women aged 18 - 20 years showed that the frequency of sexual activity in women is associated with stress, and the frequency of sexual activity in women with stress is higher than in women without stress (38).

Relying on the current study, anxiety, depression, unemployment, or unstable employment status were among the main influential factors in female sexual function. In a study by Chatterjee et al., female gender and depression were associated with sexual dysfunction during the quarantine related to the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings show the impact of poor mental health on sexual dysfunction and the importance of paying attention to women’s mental health during the epidemic (39). Artymuk et al. concluded that COVID-19, along with lifestyle changes, quarantine, and income reduction, imposed significant stress and affected the reproductive and sexual health of women worldwide, leading to a general reduction in female sexual activity by up to 40%. Most studies also reported a reduction in sexual desire and arousal (40). A review study by Masoudi et al. showed that restrictions due to COVID-19 could be associated with a greater amount of sexual weakness and decreased sexual activity (41). A review study conducted by Dashti et al. showed no significant drop in the scores of female sexual function and other areas compared to before the epidemic (42). These contradictory outcomes can be ascribed to the small number of studies conducted in this field and a lack of reports of the illness peak, the level of life setting, and public stress in the literature. Sexual health is a momentous part of somatic and mental health. Since crises, such as COVID-19, can lessen the quality of sexual life and limit access to services, health policymakers are recommended to consider screening regarding sexual function while also focusing on improved access to services. According to the results of this study and the high risk of sexual dysfunction in women and especially in female healthcare workers, it is necessary to conduct further studies to evaluate and compare the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women before, during, and 1 or 2 years after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Large sample size and homogeneity are some of the strengths of this study. Conducting studies in various countries and the extensive geographical diversity can be another strength of the study. Limitations in the number of studies comparing female sexual function before and during the COVID-19 crisis were considered the main limitation of the study, making it difficult to draw decisive conclusions.

5.1. Conclusions

Adverse psychological outcomes and restrictions caused by the COVID-19 crisis decreased female sexual function and the repetition of sexual activity. Health policymakers worldwide should design and implement effective plans and interventions to reduce the adverse effects of COVID-19 on the sexual health of individuals.