1. Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most prevalent type of dementia, is characterized by progressive memory impairment and cognitive decline. The accumulation of intraneuronal tau and extraneuronal amyloid β (Aβ) plaques are 2 main pathological features of AD (1, 2). The Aβ is derived through proteolytic cleavage from a transmembrane protein, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) (3, 4). The hippocampus, a brain structure linked to memory, undergoes atrophy in AD as a result of neuro-inflammation and neuronal death (5, 6). Indeed, Aβ accumulation activates pro-inflammatory microglia and induces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and nitric oxide (NO), leading to neuronal death (7, 8). This distinct role of neuro-inflammation in the pathogenesis of AD has led researchers to develop novel inflammation-modulating treatments for AD (9, 10).

Natural products have recently been considered as alternative therapeutic agents against AD (11, 12). They are derived from medicinal herbs, fruits, and their semisynthetic derivatives, making up 40% of all medicines. Moreover, they are widely administered as an alternative therapy for neurodegenerative and autoimmune disorders, as well as cancer and cardiovascular disease (13, 14). Low toxicity and lack of side effects make them a promising option for efficient therapy (15). Flavonoids are one of the main natural polyphenolic metabolites that target multiple signaling pathways (16). Recently, the flavonoid naringin has significantly attracted research interest. Naringin, as a flavanone glycoside, is abundant in citrus fruits such as oranges, lemons, bergamots, and grapefruit (17). In Chinese alternative medicine, naringin is an active compound with wide utilization (17). Naringin is known for several biological and pharmacological properties, such as neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-oxidant effects (16, 18-20). Also, naringin has been shown to recover neurobehavioral defects by ameliorating oxidative stress in the brain (21). In a study by Kaur and Prakash, it was demonstrated that the administration of naringin improved memory function and reduced oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in a neurotoxicity model in rats. Additionally, naringin reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α), acetylcholinesterase, and amyloid deposition (22).

2. Objectives

In the present study, we evaluated the effect of naringin on scopolamine (SCO)-induced inhibitory passive avoidance memory impairment, the total number of amyloid plaques, and the volume of the hippocampal CA1 area using stereological methods.

3. Methods

3.1. Animals and Ethical Statements

The study was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978) for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experiments received approval from the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran. Adult male Wistar rats (180 - 220 g) were purchased from Pishro Mehravaran Azma Pars (Babul, Iran) and housed in plastic cages under controlled conditions, including a temperature of 23 ± 1°C, a 12: 12 light/dark cycle, and free access to food and water.

3.2. Experimental Design

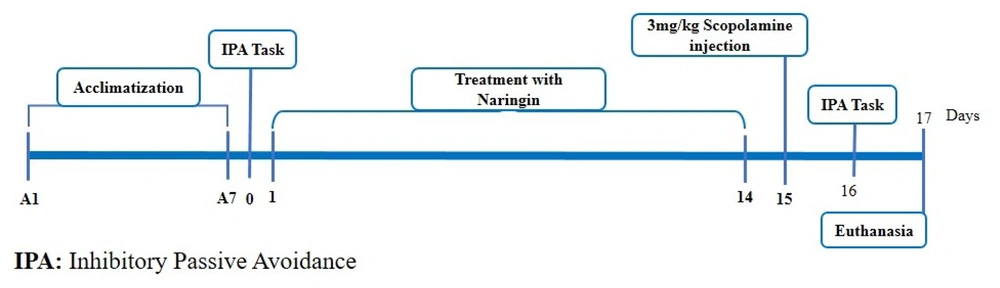

The rats were randomly divided into 5 groups, with 8 rats in each group, as follows: Control, saline + SCO, naringin 50 mg/kg/day + SCO, naringin 100 mg/kg/day + SCO, and naringin 200 mg/kg/day + SCO.

The control group received no intervention. The saline + SCO group was pretreated with 200 µL of saline per day for 14 continuous days. The 3 treatment groups were pretreated with 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg/day of naringin, administered intraperitoneally (IP) for 14 days, respectively (23).

After the 14-day intervention, the saline + SCO and 3 treatment groups were injected with a single dose of SCO (3 mg/kg, IP) (24) to induce an AD-like condition (Figure 1).

3.3. Passive Avoidance Test

Memory function was evaluated using the passive avoidance task, which consists of 3 steps: Adaptation, training, and probing.

In the adaptation step, rats were introduced to the chamber. In this regard, the rats were placed inside the light chamber, and 60 s later, the guillotine door was opened, the rat entered the dark chamber by innate photophobia and the time taken to enter the dark compartment (the step-through latency in the acquisition, STLa) was recorded after opening the guillotine door.

For the training step, the rat was gently placed inside the light chamber, and then the gate was opened; upon entry to the dark compartment, a 50 Hz, 1 mA, 3 seconds, foot shock was given. Two minutes later, the rat was returned to the light compartment; in this step, if the rat did not enter the dark compartment for 120 seconds, the successful training was accepted.

In the probe step, memory retention was assessed. Each rat was placed in the light compartment, and the step-through latency time was recorded within 300 seconds (24).

3.4. Tissue Preparation

Twenty-four hours after the behavioral assessment, the rats were deeply anesthetized with IP injections of ketamine and xylazine. After transcardial perfusion, the brains were harvested and fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 7 days. An automated tissue processor (Did Sabz, Iran) was used for histological processing, and the brains were embedded in paraffin. Serial coronal sections (26 μm thickness) were obtained using a rotary microtome (Pooyan MK 1110, Iran). The sections were stained with Congo red (DDK, Italy).

3.5. Congo Red Staining

Congo red staining was performed to detect Aβ plaques. In brief, the sections were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated through a series of ethanol solutions (100%, 96%, 70%, and 50%). Following rinsing the sections in tap water, the brain sections were incubated with a 1% Congo red solution at 25°C for 60 minutes. Then, the brain sections were rinsed in tap water. Next, the brain sections were stained with Mayer's hematoxylin solution to stain the nucleus. Finally, the slides were dehydrated with 95% and 100% ethanol, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped with Entellan (Merck, Germany) (25).

3.6. Stereological Methods

3.6.1. Estimation of the CA1 Volume

The volume of the CA1 area was estimated using the Cavalieri principle. Brains were cut into serial coronal slices. Afterward, using systematic uniform random sampling, 10 - 12 sections were selected. Under the stereomicroscope, regions of interest in each section were selected according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (26). The volume of CA1 was determined using the following formula:

Where “ΣA” is the sum of the interest area, and “d” is the distance between the sampled sections (27, 28).

3.6.2. Estimation of the Number of Congophilic Aβ Plaques in the CA1 Area

The number of congophilic Aβ plaques was counted in 10 - 12 sections of each brain using the optical dissector method. A computer with stereological software (StereoLite, GOUMS, Gorgan, Iran) connected to a light microscope was used to evaluate the total number of pyramidal cells. The microscopic fields were selected based on systematic uniform random sampling, with equal distances between sampling areas in the X and Y directions. A microcator (Heidenhain MT12, Germany) attached to the microscope stage was used to measure the Z-axis movement. The counting frame was a probe with acceptance and forbidden lines, which was used to count the cells. Any plaque, whether partially or entirely inside the counting frame and not touching the forbidden line, was counted. The numerical density (Nv) was estimated using the following formula:

Where ΣQ− is the total number of counted plaques, ΣP is the total number of counting frames, a/f is the area per frame, h is the height of the dissector, t is the mean section thickness calculated by the microcator, and BA is the microtome setting. The total number of congophilic Aβ plaques in the CA1 area was calculated by multiplying the Nv by the volume of the CA1 (28, 29).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS v. 16.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The data were checked for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were reported as means ± standard deviation (SD), and significant differences between the group means were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post-hoc LSD (least significant difference) test. The statistical significance was considered P < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Naringin Restored Learning and Memory Performance in Scopolamine-Receiving Rats

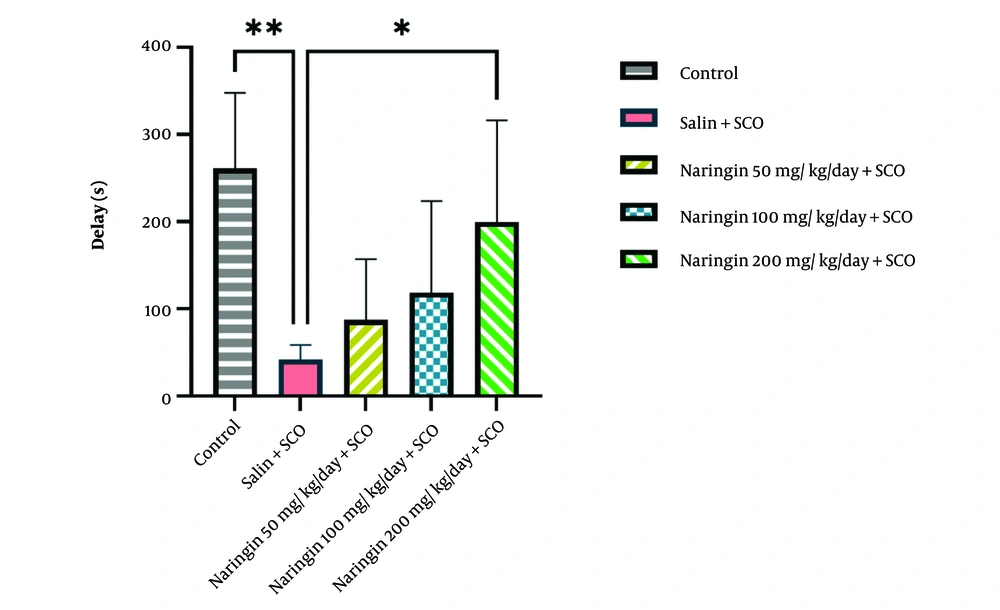

Data from the passive avoidance test indicated that SCO injection significantly decreased the step-through latency time compared to the control group (P < 0.01, Figure 2). Injection of naringin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) improved the step-through latency time compared to the saline + SCO group. The statistical analysis revealed that the effect was more evident in the naringin 200 mg/kg + SCO group (P < 0.05, Figure 2).

Naringin restored scopolamine (SCO)-induced memory impairment. Passive avoidance test analysis showed that the step-through latency time decreased in the saline + SCO group compared to the control group (P < 0.01). Pretreatment with naringin (14 continuous days) restored SCO-induced memory dysfunction (mean ± SD) (P < 0.05). One-way ANOVA and post-hoc LSD analysis (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; and ****P < 0.0001).

4.2. Naringin Preserved the Volume of the Hippocampal CA1 Area

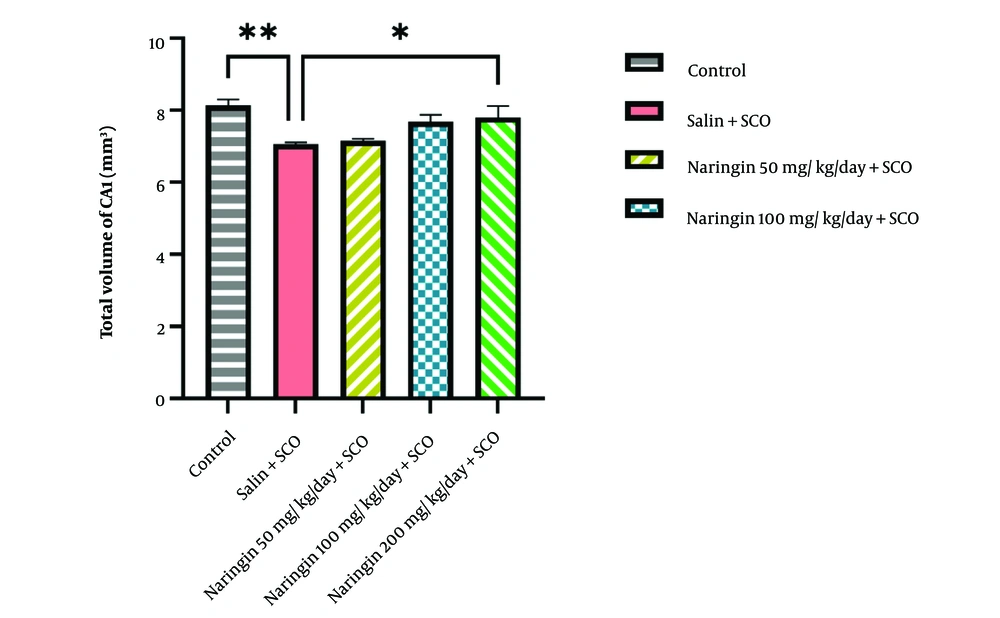

Stereological analysis showed that SCO injection significantly reduced the hippocampal CA1 volume compared to the control group (P < 0.05, Figure 3). Among the various doses of naringin, administration of 200 mg/kg of naringin significantly preserved the volume of CA1 relative to the saline + SCO group (P < 0.05, Figure 3).

Naringin rescued hippocampal CA1 volume. Stereological analysis showed that the scopolamine injection in the saline + SCO group significantly reduced hippocampal CA1 volume compared to the control group (P < 0.01). Naringin injection in 3 treatment groups preserved hippocampal CA1 volume; the most effective dose was 200 mg/kg of naringin (P < 0.05) (mean ± SD). Scale bar: 20 µm. One-way ANOVA and post-hoc LSD analysis (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; and ****P < 0.0001).

4.3. Naringin Diminished Aβ Plaque Density in the Hippocampal CA1 Area

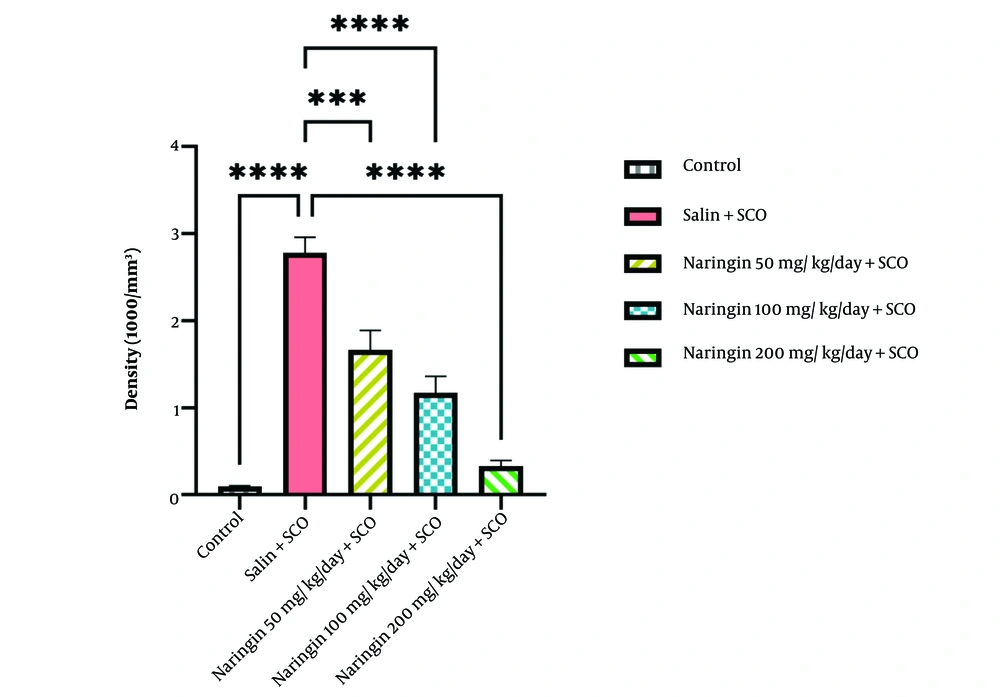

The results indicated that SCO significantly increased the density of Aβ plaques in the hippocampal CA1 area in contrast to the control group (P < 0.0001, Figure 4). All 3 treatment groups, i.e., naringin 50 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.001), naringin 100 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001), and naringin 200 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001), showed that injected naringin significantly decreased the density of Aβ plaques in the CA1 area in comparison with the saline + SCO group (P < 0.001, Figure 4). Among the naringin-received groups, the naringin 200 mg/kg + SCO group showed superior effects on decreasing the density of Aβ plaques (P < 0.0001, Figure 4).

Naringin declined the density of scopolamine (SCO)-induced congophilic Aβ plaques. Congo red staining analysis revealed that scopolamine injection enhanced the density of congophilic Aβ plaques in the saline + SCO group in the hippocampal CA1 area compared to the control group (P < 0.0001). Pretreatment with naringin decreased the density of congophilic Aβ plaques in three treatment groups: Naringin 50 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.001), naringin 100 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001) and naringin 200 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001), compared with saline + SCO group (mean ± SD). Scale bar: 20 µm. One-way ANOVA and post-hoc LSD analysis (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; and ****P < 0.0001).

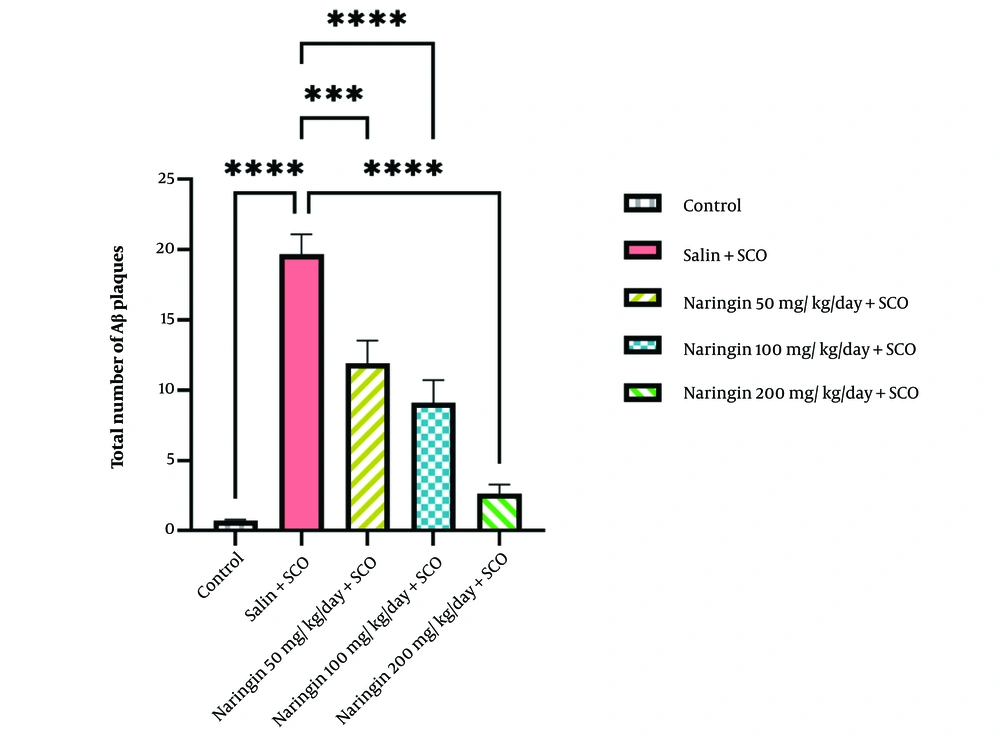

4.4. Naringin Decreased the Total Number of Aβ Plaques in the Hippocampal CA1 Area

Scopolamine significantly increased the total number of Aβ plaques in the CA1 area of the hippocampus relative to the control group (P < 0.0001, Figure 5). Injection of naringin significantly decreased the total number of Aβ plaques in the CA1 area when compared to the saline + SCO group for 50 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.001), naringin 100 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001), and naringin 200 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001) (Figure 5). The most effective dose was 200 mg/kg naringin (P < 0.0001, Figure 5).

Naringin reduced the total number of scopolamine (SCO)-induced congophilic Aβ plaques. Congo red staining analysis showed that scopolamine injection enhanced the total number of congophilic Aβ plaques in the saline + SCO group in the hippocampal CA1 area relative to the control group (P < 0.0001). Pretreatment with naringin reduced the total number of congophilic Aβ plaques in 3 treatment groups: Naringin 50 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.001), naringin 100 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001) and naringin 200 mg/kg/day + SCO (P < 0.0001) relative to saline + SCO group (mean ± SD). Scale bar: 20 µm. One-way ANOVA and post-hoc LSD analysis (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; and ****P < 0.0001).

5. Discussion

In the present study, the therapeutic effects of naringin, a known neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-oxidant flavonoid, were evaluated. Our data showed that naringin restored SCO-induced memory deficit and also reduced the density and total number of beta-amyloid plaques in the hippocampal CA1 area in a rat model of AD. Furthermore, naringin preserved the hippocampal CA1 volume.

Fear memory is associated with harmful situations that help humans learn from past traumatic experiences and avoid related threats in the future (30). The passive avoidance test is a fear-aggravated test used to assess memory functions in rodents (30). The hippocampal–amygdala circuit is associated with fear memory. Projections of CA1 pyramidal neurons to the amygdala are necessary for encoding fear memory (31). In this study, memory impairment was induced by SCO. Scopolamine-related pathological changes model the pathology of AD and cause Aβ accumulation, neuro-inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, cholinergic dysfunction, and neuronal apoptosis (32).

Our research found that IP-injected SCO impaired the ability to learn and memorize. Scopolamine significantly increased the density and total number of beta-amyloid plaques and decreased the volume in the hippocampal CA1 area.

The present results are similar to those of Assi et al., who demonstrated that SCO reduced memory function (33). Administration of SCO enhanced Aβ plaques in the rat hippocampus (25). Also, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the human brain has shown lower hippocampal volume in AD patients (34).

Natural products have played a major role in novel drug discovery for AD (35). Flavonoids are defined as the first line of natural phenolic compounds (36). Naringin, the citrus fruit's flavonoid, is known for its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-cancer effects (37).

The current study showed that treatment with naringin ameliorated the memory impairment in the passive avoidance test. Golechha et al. demonstrated that pretreated IP naringin improved memory performance in the passive avoidance task in a seizure model. Naringin acted like an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory agent, consequently protecting neurons (38). Wang et al. observed that naringin could upregulate calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) activity, an important synaptic target for Aβ, which is active in the learning and memory pathway, in a transgenic mouse model of AD (39). In agreement with these results, the efficiency of naringin was reported in Huntington's disease (40) and diabetes (41). It should be noted that, as shown here and in other studies, naringin restored memory function in a dose-dependent manner (200 > 100 > 50 mg/kg) (38, 39).

In this study, we observed that 200 mg/kg of naringin significantly improved the hippocampal volume in the CA1 region. In general, hippocampal volume can be associated with neuronal number, size, and density in its subfields (42). It is shown that naringin behaved as a neuroprotective agent and protected the hippocampal CA1 neurons against the neuro-inflammation and autophagic stress effects of kainic acid (43). Also, TUNEL and Nissl staining depicted that neuronal survival and structure in the hippocampal CA1 region were preserved following naringin treatment through modulating apoptosis, neuro-inflammation, oxidative stress, and glutamate metabolism, resulting in enhanced cognition (44).

Our stereological analysis revealed that naringin could reduce the density and total number of amyloid plaques in the hippocampal CA1 area. Multiple mechanisms are suggested for the neuroprotective effects of naringin. Indeed, naringin reduces inflammation by inducing M2 microglia (anti-inflammatory), leading to a decrease in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (41), and promoting Aβ clearance, resulting in the restoration of memory performance in the AD model (45-47). Moreover, naringin downregulates the expression of the NFKB1 gene, which plays a key role in regulating the immunological response (48). Data reveal that, as an anti-oxidant, naringin decreases the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and NO while restoring the levels of superoxide dismutases (SOD) and catalase (CAT) (40, 49). Prakash et al. reported that naringin protects against mitochondrial oxidative damage, leading to memory enhancement in an aluminum chloride-induced rat model of AD (50). This flavonoid also reestablishes mitochondrial complex enzyme activities in a D-galactose-induced aging model (51). Furthermore, naringin influences both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways, behaving as an efficient anti-apoptotic polyphenolic compound. A study by Ben-Azu et al. showed that naringin inactivates acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme in mice brains, leading to an enhancement in acetylcholine levels and an improvement in memory function (49). The most recent research has demonstrated the neuroprotective effects of naringin, reducing the levels of Aβ, APP, and tau proteins in the hippocampus of a mouse model of AD (52). In the current study, since the effects of 200 mg/kg naringin were superior to other doses, the lack of a group solely receiving naringin at a dose of 200 mg/kg in a normal brain condition to better understand its efficiency in the brain was a limitation that is suggested to be evaluated in future studies.

Our findings, taken together, suggest the modulating effect of the flavonoid naringin on learning and memory, amyloid plaques, and the volume of the hippocampal CA1 area in a rat model of AD, demonstrating its potential therapeutic effects on AD.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown the effective role of naringin in improving memory performance, reducing the number of amyloid plaques, and preserving the hippocampal CA1 volume in a SCO-induced AD rat model. This study is in concordance with previous molecular studies on naringin's function in the AD brain.