1. Background

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by mood swings, such as mania and depression (1). This disorder is also identified by considerable morbidity and mortality, including psychosocial impairment, poor quality of life (QOL), and suicidality, in addition to debilitating mood symptoms (2-4). Nonetheless, there is increasing recognition that drug therapy fails to completely control the symptom fluctuations of BD (5). Bipolar patients experience various psychosocial, occupational, and functional problems despite taking medication (6).

Although heredity plays a vital role in the etiology of the disorder, psychosocial and family stressors are the reasons for the variation in the course of the disorder (7). Expressed emotion (EE) has strongly influenced the course of BD (8). The disruptive family environment can affect the frequency and timing of relapses. Adults with BD who live with highly critical, hostile, or emotionally overinvolved (high EE) parents are significantly more likely to experience a relapse. They experience severe stress before the onset of the disorder. Stress can trigger depression, mania, and especially sleep disturbances (9).

Previous studies have indicated that patients with BD experience high stigma (10). Bipolar symptoms also affect other family members (11). Having a family member with BD increases the suffering and threatens the mental health of other family members (12, 13). Many interventions have been implemented to combat the stigmatization; however, anti-stigma programs should remain the essential tasks of mental health programs (14).

Previous studies suggest that drug therapy and family interventions can reduce family stress, improve psychosocial functioning, and cope with environmental stressors in patients with BD (15). Therefore, individuals with BD should learn solutions to effectively deal with stressors. The patient and their family should be helped to identify the warning signs of recurrence to quickly treat the patients (16). Intervention for this group should include both the patients and their caregivers.

Family-focused therapy (FFT) is one of the evidence-based therapies for the treatment of BD. It was developed by Miklowitz and Chung and consisted of 21 sessions of psychoeducation, communication training, and problem-solving skill training. This approach focuses on training skills to regulate emotions and improve communication. This treatment is short-term and focused on the here and now and increases the mutual trust of the patient and family members (17). Studies have revealed that individuals with BD who received FFT had better medication adherence and global functioning scores over 1 year of treatment than those who only received medication (8, 18).

2. Objectives

Several studies have been conducted in Iran in this field. Some studies have focused on educating patients, while others have focused on primary caregivers (12). Considering the dual relationship between the consequences of this disorder in family functioning, the main question is whether the simultaneous training of both will have a better effect than the training of each alone. It seems that if both patients and family members receive the necessary training, it will be a practical step toward improving the consequences of this disorder (19). The prevailing cultural attitudes of stigma and discrimination cause a lack of understanding of patients, which leads to the social isolation of their families (20). Therefore, these attitudes are corrected in terms of welfare and mental health with group training and active participation of the patient and family members (21). We hypothesized that EE is reduced, dominant-negative attitudes disappear, and the QOL of these patients is psychologically improved by increasing family information. In addition, we hypothesized that the family directly affects the clinical outcomes. The present randomized controlled trial investigated.

The efficacy of FFT in combination with drug therapy on emotional expression and stigma as primary outcome and quality of life as a secondary outcome in patients and their primary caregivers in a hospital in Zahedan, Iran.

3. Methods

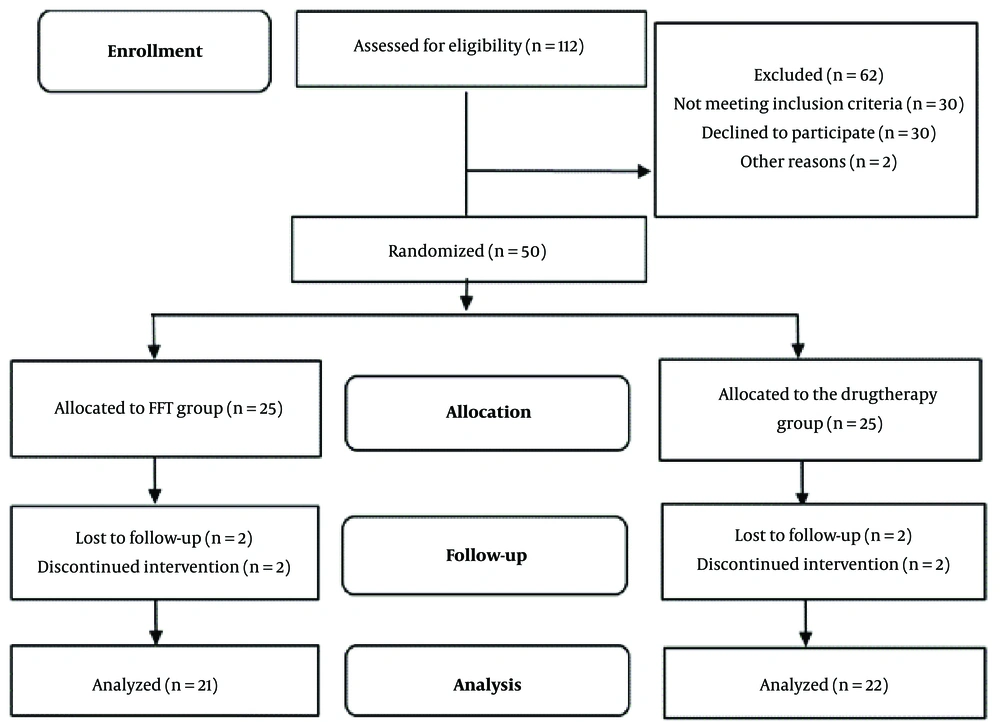

The present study is a randomized controlled trial with pretest, posttest, and 3-month follow-up, which was conducted according to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) reporting guidelines (22). The research sample was selected using available sampling. A total of 50 patients and 50 caregivers were enrolled in the study and divided into 2 groups (i.e., drug therapy group and family therapy group). The researcher generated the allocation sequence and assigned participants to groups. These patients were admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Zahedan, Iran, for the treatment of BD. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of Bipolar I disorder by a psychiatrist, higher school education, and age between 18 to 45 years. Exclusion criteria were a history of alcohol and drug abuse, brain damage, a mental disorder other than the primary diagnosis, and severe personality disorder (diagnosed by a psychiatrist). Furthermore, inclusion criteria for the primary caregivers were the age of 25 years or older and regular attendance at treatment sessions. Exclusion criteria for the primary caregivers were having psychiatric disorders and reluctance to participate in the study. The primary caregiver was defined as a person who spends most of the time providing regular care for the patient. The present study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and it has a clinical trial registration code (IRCT20201219049755N1). Also, all participants signed the informed consent form, and the data were confidentially collected.

Due to the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, treatment sessions were held with 3 patients and their family members, following health protocols and social distancing. Treatment interventions started twice a week during the hospitalization and continued after the discharge of patients. In the family therapy group, the patients and their primary caregivers also participated in the sessions. Participants were enrolled between April and September 2021, and follow-up data were collected 3 months after the end of psychotherapy (Figure 1).

3.1. Research Tools

3.1.1. Expressed Emotion Questionnaire

The Expressed Emotion Questionnaire (EEQ) was introduced by Cole and Kazarian in 1988. This questionnaire is used to assess the level of EE by the relatives of the patients and includes 60 five-choice questions (from rare to always). Each scale contains 15 questions. Individuals who score less than 116 and more than 150 on this test have low and high EE, respectively. Construct validation was investigated within a schizophrenic population. The results indicated that the EE scale had good psychometric properties of internal consistency, reliability, and construct validity (23).

3.1.2. The Modified Version of the Standard Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness

This questionnaire was designed by Ritcher et al. in 2003 and includes 17 questions that measure the label in 4 subscales of loneliness (4 questions), confirmation of stereotypes (4 questions), experience of social discrimination (4 questions), and withdrawal from society (5 questions). The scoring of the questionnaire is based on a Likert scale. On this scale, the minimum score of the label is 17, and the maximum is 68. It has a strong internal consistency (a = 0.90) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.92), as reported by Ritsher et al. (24).

3.1.3. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire–Brief

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire–Brief (WHOQOL-BREF) consists of 24 questions that assess a person's QOL in various dimensions on a 5-point Likert scale. These dimensions included 4 domains: Physical dimension, psychological dimension, social relations, and living environment. The measure demonstrated high internal consistency and adequate discriminant validity (25).

3.1.4. Family-Focused Therapy

Miklowitz and Goldstein designed FFT. It is a 21-session group therapy for adults with BD living with their families. These sessions are held once or twice a week for an hour. This treatment also has a short 12-session form. Due to the vast number of sessions, the treatment protocol was held in 15 sessions twice a week (8) (Table 1).

| Meeting | Phase | Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 | Psycho-education training | Participants (patient and family members) become familiar with the symptoms of BD, how the disorder occurs, the role of genetic-biological factors and stress in this disorder, drug therapies, and the importance of stress management strategies. |

| 5 to 9 | Communication skill training | Helping participants deal with stressors, Restriction of family relationships after a period of disruption |

| 10 to 15 | Problem-solving and summarizing skill training | Establishing and encouraging dialogue between family members about conflicting topics. Helping family members find a framework for defining, creating, evaluating, and applying practical solutions to family problems. |

Abbreviation: BD, bipolar disorder.

4. Results

Twenty-five patients in the family therapy group received FFT with their caregivers. Two patients were excluded from the study due to recurrence. One patient and 1 caregiver dropped out in the follow-up. In addition, 3 patients in the drug therapy group dropped out of the study. The family therapy group consisted of 16 men and 5 women with a mean age of 32.90 (7.45) years. The drug therapy group included 15 men and 7 women with a mean age of 30.27 (7.37) years (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Family Therapy Group (n = 21) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 22) | χ2 | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Caregivers | Patients | Caregivers | |||

| Gender | 0.45 | 0.49 | ||||

| Male | 76.19 | 69.12 | 68.18 | 65.15 | ||

| Female | 23.81 | 30.88 | 31.82 | 34.85 | ||

| Education | 6.31 | 0.17 | ||||

| Primary school | 13.6 | 16.70 | 4.5 | 14.15 | ||

| Middle school | 54.5 | 40.18 | 40.9 | 33.70 | ||

| Academic | 31.7 | 43.12 | 54.5 | 52.15 | ||

| Marital status | 5.67 | 0.05 | ||||

| Married | 40.9 | 65.12 | 50 | 69.19 | ||

| Unmarried or divorced | 59.1 | 34.88 | 50 | 30.81 | ||

| Work status | 3.256 | 0.51 | ||||

| Employed | 85.5 | 81.81 | 54.5 | 85.01 | ||

| Unemployed | 10 | 11.17 | 36.4 | 6.85 | ||

| Housewife | 4.5 | 7.12 | 9.1 | 8.14 | ||

| Family history of BD | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 59.1 | 59.1 | ||||

| Negative | 40.9 | 40.9 | ||||

| Main caregiver | 5.20 | 0.15 | ||||

| Mother | 18.2 | 50 | ||||

| Father | 36.4 | 18.2 | ||||

| Partner | 45.4 | 23.2 | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | 7.58 | 0.05 | ||||

| Weak | 18.2 | 4.5 | ||||

| Moderate | 50 | 27.3 | ||||

| High | 31.8 | 68.1 | ||||

Abbreviation: BD, bipolar disorder.

a Values are presented as %.

Pretest and post-test scores were compared using the Stigma Questionnaire (SQ) and EEQ in contrast to the drug therapy group, which is presented in Table 3. The score of QOL (the QOL of SF-26 is shown in Table 3.

| Pretest | Posttest | Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Therapy Group (n = 22) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 21) | Family Therapy Group (n = 22) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 21) | Family Therapy Group (n = 22) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 21) | |

| Stigma | ||||||

| Loneliness | 11.36 ± 4.05 | 9.68 ± 2.86 | 9.18 ± 2.28 | 9.50 ± 2.75 | 8.90 ± 2.44 | 9.27 ± 2.96 |

| Confirmation of stereotypes | 10.27 ± 2.25 | 9.00 ± 1.66 | 9.00 ± 2.02 | 8.81 ± 1.76 | 8.95 ± 2.53 | 8.86 ± 2.07 |

| Experience of social discrimination | 9.95 ± 3.06 | 9.40 ± 2.10 | 9.09 ± 2.42 | 9.40 ± 2.10 | 8.95 ± 2.66 | 9.13 ± 2.27 |

| Withdrawal from society | 13.90 ± 4.77 | 11.63 ± 3.30 | 11.77 ± 3.00 | 11.72 ± 3.29 | 12.77 ± 5.27 | 11.54 ± 3.12 |

| Total score | 45.50 ± 13.09 | 39.72 ± 8.87 | 39.04 ± 8.30 | 39.45 ± 8.64 | 39.59 ± 10.18 | 38.81 ± 9.24 |

| Emotion expressed | ||||||

| Emotional response | 34.81 ± 7.08 | 40.81 ± 5.05 | 30.90 ± 3.98 | 39.18 ± 6.82 | 31.54 ± 4.61 | 39.59 ± 6.83 |

| Negative attitude toward disease | 34.22 ± 6.99 | 36.45 ± 8.03 | 25.45 ± 4.03 | 35.13 ± 9.25 | 27.09 ± 4.16 | 34.95 ± 9.13 |

| Tolerance | 39.40 ± 11.84 | 39.63 ± 4.75 | 31.72 ± 3.61 | 38.90 ± 5.71 | 32.40 ± 2.95 | 38.95 ± 5.95 |

| Harassment | 39.45 ± 5.47 | 39.36 ± 3.20 | 35.77 ± 3.68 | 38.50 ± 3.33 | 36.04 ± 3.72 | 37.86 ± 3.91 |

| Total score | 147.90 ± 25.69 | 156.27 ± 13.87 | 126.59 ± 9.33 | 146.77 ± 16.77 | 124.95 ± 10.15 | 148.86 ± 16.91 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 3 shows the mean and SD of the stigma and EEs and their subscales. Significant differences were found in EE between the 2 groups, indicating the treatment efficacy over time in the post-test and follow-up. This difference reflected the effectiveness of FFT in the family therapy group (t32.86 = -4.930; P = 0.001) in all variables.

In stigma, there was a difference in the mean of the 2 groups, but this difference was not statistically significant (t36.93 = -1.71; P = 0.095.

Table 4 shows the mean and SD of QOL. A significant difference was observed in 2 domains: Mental health and social health (t42 = 2.06; P = 0.001); however, this difference was not statistically significant in the somatic and environment domains between the 2 groups.

| Domains of Quality of Life | Pretest | Posttest | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Therapy Group (n = 22) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 21) | Family Therapy Group (n = 22) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 21) | Family Therapy Group (n = 22) | Drug Therapy Group (n = 21) | |

| Physical health | 21.18 ± 4.67 | 19.13 ± 2.71 | 22.13 ± 4.63 | 19.09 ± 2.78 | 24.31 ± 4.99 | 22.36 ± 4.52 |

| Mental health | 18.63 ± 4.25 | 15.18 ± 3.91 | 30.72 ± 3.08 | 15.04 ± 3.61 | 31.31 ± 4.45 | 16.68 ± 4.22 |

| Social health | 4.45 ± 1.87 | 4.95 ± 2.14 | 12.22 ± 1.87 | 4.40 ± 1.53 | 12.50 ± 3.019 | 4.45 ± 1.71 |

| Environment health | 14.00 ± 3.22 | 15.77 ± 6.80 | 15.72 ± 3.38 | 14.36 ± 4.47 | 22.59 ± 6.42 | 14.31 ± 4.68 |

| Total score | 65.86 ± 10.02 | 62.42 ± 15.59 | 89.31 ± 8.96 | 59.09 ± 10.73 | 95.50 ± 15.44 | 59.00 ± 11.98 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

The present study aimed to determine the effectiveness of FFT in combination with drug therapy compared to drug therapy alone in EE, stigma, and QOL in patients with BD. The assessment was performed at the baseline, after the intervention, and 3 months after the end of treatment. All patients were stable when they were allocated to the study.

The present study showed a general decrease in EE in the family therapy group; such a decrease was not observed in the other group. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies (26, 27) and contradicts the conclusion of this study (28). Some studies have shown that family attitudes and interactions play an essential role in the course of BD. This disorder also affects family functioning, especially when patients and caregivers do not have enough information, and the likelihood of the recurrence of the symptoms of the disorder increases (29).

Given that a family history of BD is one of the strongest risk factors for this disorder, adverse environmental conditions activate the latent gene in other family members. Family-focused therapy strengthens empathy between patients and family members and reduces ecological stress and disturbing negative attitudes (30).

In the present study, the stigma score was not significantly lower in the family therapy group compared to that in the drug therapy group. The results demonstrated that FFT had no positive effects on the internalized stigmatization levels of patients with BD. This result is inconsistent with previous findings that showed psycho-education and skill training reduced the stigma (31). The reason for this difference is that most of the patients are male in our study. Early marriage is expected in Zahedan City due to cultural issues. Not marrying, being unemployed, feeling ashamed, and being humiliated by others due to cultural issues can cause this difference (32). Bipolar disorder negatively affects patients' help-seeking behaviors, exacerbates symptoms, makes them chronic, and affects individuals' abilities (31, 33). Evidence indicates that psychological interventions can improve the well-being of people with BD (34). Family-focused therapy effectively helps patients' families manage family problems while developing the supportive skills needed for an individual's recovery.

Another finding of this study is that patients under FFT reported better mental health and social health. According to previous studies, QOL persists in patients with BD, even in remission (35). These results suggest that FFT will likely be essential for enhancing life satisfaction, relational functioning, and health and improving sleep quality in patients with BD (36). Family can support the patient when they feel that they are part of the treatment team. This cooperation provides the necessary information about the nature of the disease, increases mutual understanding and acceptance of the person as a patient, promotes more effective coping with stress triggers, and prevents the recurrence of the disorder by creating favorable family conditions (37). As a result of this treatment, caregivers will be treated with social support behaviors and behavioral embarrassment and stigma will be reduced. Adaptation to stigmatization will be reduced as social support is a well-established buffer against the recurrence of mania (38). Research has shown that FFT affects the family's attitude toward the patient and the disease and increases therapeutic alliance, consequently facilitating the healing process. It can also improve patient management and lead to self-management with proper guidance. However, the negative feedback of these patients regarding the regular use of their medications and adherence to treatment instructions are more challenging to correct with individual training. Because this treatment is conducted in group formats, it can more effectively eliminate these defects (39).

5. Discussion

Living with a person with BD can cause a lot of stress and tension in the family. In addition to the challenge of coping with the symptoms and outcomes of the disorder, family members often struggle with feelings of guilt, fear, anger, and helplessness, which can cause severe problems in their relationship. Family-focused therapy teaches patients and their caregivers better ways to cope with the disorder and helps them understand their limitations. Learning stress reduction methods, implementing a regular daily schedule, familiarity with signs and symptoms of relapse, appropriate communication skills, and training in problem-solving will be essential steps in treating this disorder. One of the strengths of this treatment is its clarity and ease of implementation and the use of practical examples to better understand the concepts. One of the treatment weaknesses is its numerous sessions, which can be shortened according to the culture.

5.1. Study Limitations

The different levels of intelligence of patients and their families, limitations due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and small sample size (which limits the generalization of results to a larger community) are limitations of this study. The present study is extracted from a PhD thesis and is one of the first studies (to the best of our knowledge) that investigated the effectiveness of FFT in patients with BD and their caregivers in Iran. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to ensure the generalizability of the results.