1. Background

The loss of a loved one is an exceedingly distressing and sorrowful experience. However, most individuals manage the acute stress and grief associated with loss without enduring prolonged adverse effects (1). Clinically significant are those who fall within the realm of bereavement syndrome, constituting about 10 - 15% of individuals who endure persistent and incapacitating symptoms linked to grief. This condition, which is described as ‘protracted’ or ‘complex’ grief, exerts profound and enduring impacts on overall well-being and functional roles, extending beyond the realms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (2-4). While some debate exists regarding the precise combination of symptoms associated with enduring grief, most theorists concur that it involves intense yearning for the departed (manifested as the pain of separation), intrusive thoughts and images, memory avoidance, emotional numbness, anger, and, often, feelings of guilt. Additionally, there is a sense of loss, emptiness, heightened reactions to reminders, and difficulties in forging new identities, forming fulfilling relationships, and engaging in meaningful activities. These symptoms not only impact mental health but can also lead to elevated rates of mortality, physical health issues, substance abuse, and suicide. Reflecting these concepts, the proposed revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, now includes “bereavement disorder” as an adjustment disorder encompassing these symptoms (5, 6). With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, a surge in grief cases has arisen due to its risk factors, including sudden, unforeseen, seemingly preventable, and arbitrary deaths, individuals passing away in isolation, constraints on visiting dying family members, physical distancing policies impacting funerals, burials, rituals, and support for those grieving, concerns about unemployment, feelings of insecurity, financial instability, apprehensions about contagion, and concerns for the welfare of others (7).

Several psychological interventions are associated with addressing grief, one of which is compassion-focused therapy (CFT). Numerous studies have revealed that higher self-compassion (SC) is linked with reduced anxiety and depression (8, 9). Limited information exists concerning protective and risk factors influencing the development of psychopathology in individuals mourning the loss of a loved one. Self-compassion represents a potential protective factor and correlates with an individual’s capacity to acknowledge their pain, failures, and imperfections. One way in which SC diminishes emotional distress is by acting as a buffer against rumination on grief (1, 10). Another psychological treatment that has demonstrated its efficacy in ameliorating major depressive disorder (MDD) and is employed for complicated grief is interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Interpersonal psychotherapy is a structured, time-limited psychological intervention originally developed for managing major depression during the 1970s. It follows a concise treatment course comprising three specific phases: (1) Identifying the problem area that requires intervention, (2) addressing the specified areas, and (3) concluding the treatment by consolidating the gains achieved during therapy and preparing the patient to continue working independently (11, 12).

2. Objectives

This study sought to explore the effectiveness of CFT and IPT among individuals experiencing grief precipitated by the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study employed a randomized (simple random allocation), double-blinded clinical trial design. The study’s target population comprised individuals who had experienced the loss of a family member between March 2019 and September 2020 due to a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of COVID-19 after being admitted to one of the referral hospitals in Isfahan, Iran.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria encompassed the following: A first-degree relative’s demise as a result of COVID-19 within the past 6 months, a grief questionnaire score surpassing 34, the individual’s voluntary consent to engage in treatment, age exceeding 18 years, and the absence of a major psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, personality disorder) or substance abuse disorder, which was ascertained through an interview conducted by a psychiatric resident.

Exclusion criteria encompassed non-participation in treatment sessions for more than 2 consecutive sessions and symptom exacerbation necessitating psychiatric hospitalization.

3.3. Study Protocol

After enrollment, patients underwent interventions using either the IPT or CFT methods. Trained clinical psychologists conducted the treatments through online sessions. These treatments were individualized, consisting of 6 weekly sessions, each lasting between 60 to 90 minutes.

The IPT encompassed the following components: (1) Teaching depression symptoms; (2) correcting relationships, including examining the history of the relationship with the deceased and exploring causes of discomfort during mourning (e.g., excessive intimacy, guilt due to work-related issues, anger towards the deceased); (3) expanding relationships with the deceased, which involved examining positive interactions during the deceased’s lifetime, evaluating the individual’s capacity to cope with the loss, and transitioning from idealized handling to real handling within their abilities; (4) expanding relationships with other relatives and family members, including communication analysis, assessing the quality and quantity of previous relationships, and role-playing for verbal communication, expressing emotions, and self-disclosure.

The content of CFT sessions included: (1) Introduction to the general concepts of SC and empathy, along with rhythmic calming breathing exercises; (2) teaching self-criticism and its various types; (3) encouraging individuals to evaluate themselves as self-critics or compassionate; (4) explaining the causes and consequences of self-criticism; (5) offering solutions to reduce self-criticism; (6) guiding patients in keeping a daily mistake journal, identifying reasons for errors, recognizing the drawbacks and consequences of not forgiving, and practicing non-judgmental acceptance of mistakes using mindfulness and related techniques; (7) practicing self-appreciation and self-worth by acknowledging positive qualities; (8) training in creating mental images of compassion and relaxation; (9) practicing writing self-loving phrases; (10) identifying conflicting feelings using the Gestalt empty chair technique and training inner dialogue involving self-criticism, SC, and compassionate self; (11) guiding individuals to write a compassionate letter to themselves (10).

Participants underwent evaluations before the initiation of the sessions and 1 month following the conclusion of the treatment sessions. Data collection tools included the Grief Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) and the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (abbreviated version with 26 questions, WHOQOL-BREF). These questionnaires were administered to patients through an online platform. The Persian version of GEQ demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.40. Furthermore, the questionnaire’s factors exhibited appropriate convergent reliability for the 2 subscales of depression and somatization (13). Another study confirmed good to excellent reliability and acceptable validity of WHOQOL-BREF across various subject groups in Iran (14).

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS v. 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), employing chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, independent t-test, paired t-test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a significance level of 5%. This study received approval from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.519) and was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20201119049445N1).

4. Results

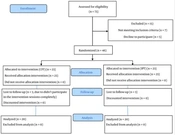

The present study involved 40 adults who had experienced grief following the loss of their first-degree relatives due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, 2 groups of 20 individuals each underwent individualized treatment using IPT and CFT. However, 3 individuals in each group were lost to follow-up sessions and did not complete the therapy. Figure 1 presents the CONSORT flow diagram illustrating the study’s progression. The GEQ and WHOQOL-BREF questionnaires were administered to assess each participant before the initiation of the therapy sessions and again 1 month after the conclusion of the treatment.

The results were analyzed using SPSS v. 26, and statistical tests, including chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, independent t-test, paired t-test, and ANOVA, were conducted at a significance level of 5%. Initial demographic and basic information was collected for each group of 20 participants, as displayed in Table 1. The findings indicated that education level (P = 0.93), job type (P = 0.24), relationship with the deceased (P = 0.12), and history of psychiatric diseases (P = 0.74) did not exhibit significant differences between the 2 treatment groups. However, there was a higher number of women in the study (P = 0.03). Additionally, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups concerning the age of the participants (P = 0.56), the age of the deceased (P = 0.66), and the interval between hospitalization and death (P = 0.16) (Table 1).

| Variables | IPT Group (N = 20) | CFT Group (N = 20) | The Value of the Test Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 6.14 | 0.03 | ||

| Female | 18 (62.1) | 11 (37.9) | ||

| Male | 2 (18.2) | 9 (81.8) | ||

| Education | 0.13 | 0.93 | ||

| Below high school diploma | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | ||

| High school diploma and bachelor’s degree | 12 (52.2) | 11 (47.8) | ||

| Master’s degree or higher | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | ||

| Occupation | 4.20 | 0.24 | ||

| Health care staff | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | ||

| Employee | 5 (41.7) | 7 (85.3) | ||

| Self-employed | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | ||

| Unemployed | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | ||

| Relationship with the deceased | 5.78 | 0.12 | ||

| Parents of the patient | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | ||

| Patient’s spouse | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | ||

| Patient’s child | 3 (100) | 0 | ||

| Patient’s sibling | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| History of psychiatric diseases | 0.10 | 0.74 | ||

| Yes | 12 (48) | 13 (52) | ||

| No | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | ||

| Age of the participant | 43.30 ± 12.96 | 41.10 ± 11.18 | 0.46 | 0.56 |

| Age of the deceased | 19.12 ± 15.30 | 17.12 ± 13.35 | 1.78 | 0.66 |

| The interval between hospitalization and death | 53.45 ± 25.13 | 63.75 ± 20.22 | 4.03 | 0.16 |

Demographic (Qualitative and Quantitative) Information of the Sample by Treatment Groups

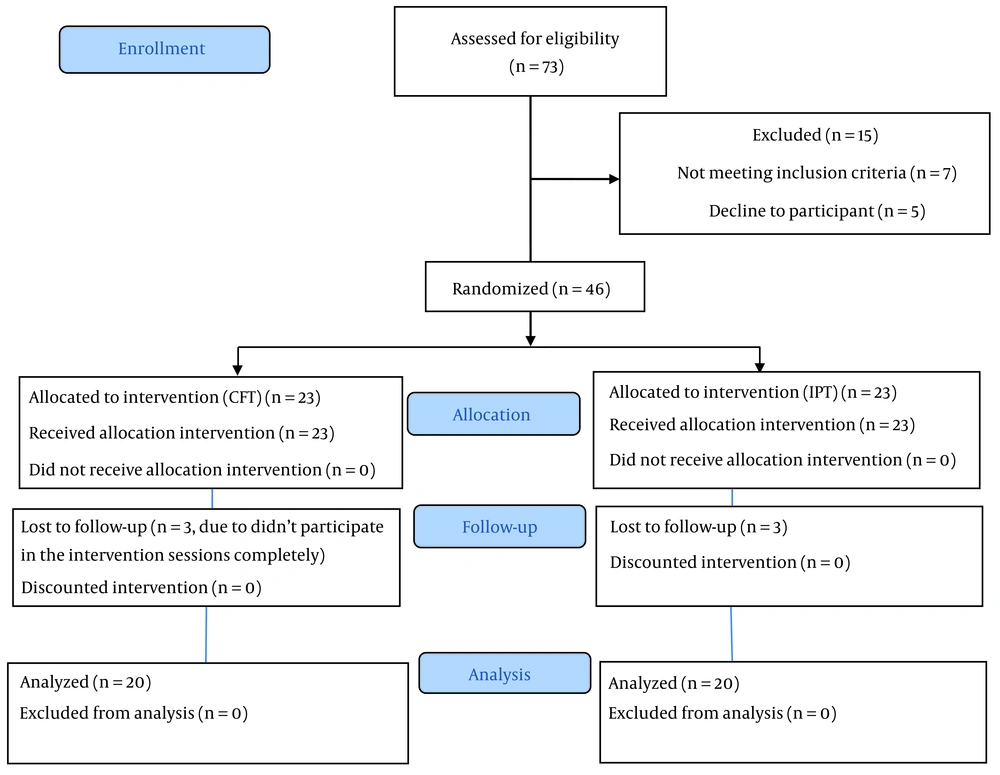

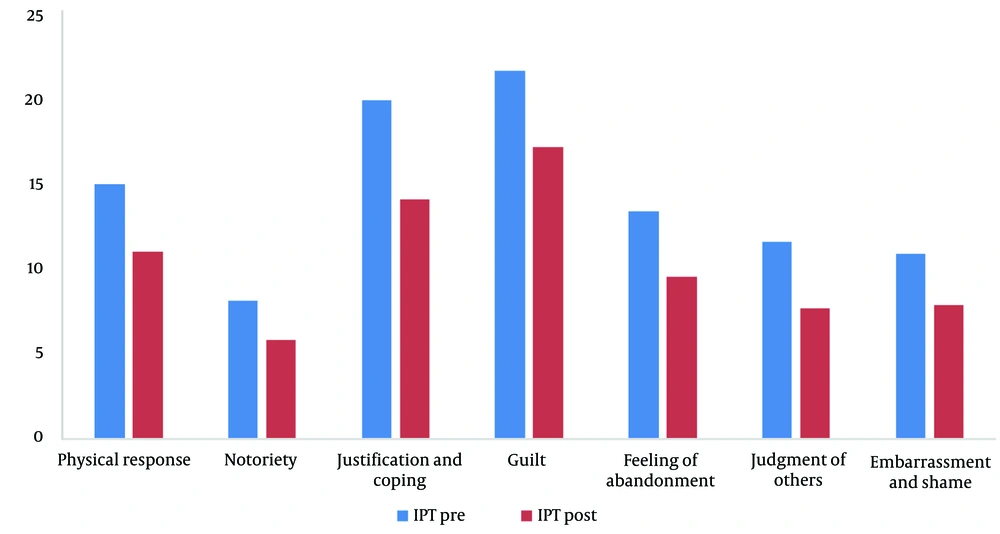

The Grief Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) was assessed across 7 domains. The results indicated significant improvements within each treatment group separately (P < 0.001). However, when comparing the 2 groups while adjusting for the pre-test effects, there were no significant differences observed in any of the domains, including physical response (P2 = 0.45), notoriety (P2 = 0.53), justification and coping (P2 = 0.59), guilt (P2 = 0.31), feelings of abandonment (P2 = 0.52), judgment of others (P2 = 0.78), and embarrassment and shame (P2 = 0.79) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Overall, the experience of grief, despite improvements in each treatment group, did not exhibit significant differences between the 2 treatment methods (P = 0.65).

| Variables | IPT Group (N = 20) | CFT Group (N = 20) | P1 b (ANCOVA) | P2 c (ANCOVA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical response | 0.45 | |||

| pre | 15.15 ± 3.75 | 15.60 ± 3.23 | 0.08 | |

| post | 11.10 ± 3.56 | 12.20 ± 2.78 | 0.29 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Notoriety | 0.53 | |||

| pre | 8.20 ± 3.34 | 8.10 ± 3.01 | 0.94 | |

| post | 5.90 ± 2.63 | 5.71 ± 2.69 | 0.58 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Justification and coping | 0.59 | |||

| pre | 20.10 ± 7.30 | 23.75 ± 5.78 | 0.21 | |

| post | 14.25 ± 5.44 | 17.25 ± 5.07 | 0.19 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Guilt | 0.31 | |||

| pre | 21.90 ± 8.68 | 20.90 ± 8.65 | 0.81 | |

| post | 17.35 ± 7.08 | 16.35 ± 6.56 | 0.13 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Feeling of abandonment | 0.52 | |||

| pre | 13.50 ± 3.60 | 12.75 ± 2.93 | 0.14 | |

| post | 9.60 ± 2.81 | 8.90 ± 3.45 | 0.35 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Judgment of others | 0.78 | |||

| pre | 11.70 ± 3.16 | 10.70 ± 2.34 | 0.81 | |

| post | 7.75 ± 2.44 | 7.45 ± 3.13 | 0.47 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Embarrassment and shame | 0.79 | |||

| pre | 11.01 ± 3.06 | 11.15 ± 3.99 | 0.46 | |

| post | 7.95 ± 3.36 | 7.85 ± 4.13 | 0.99 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||

| Total | 0.82 | |||

| pre | 101.55 ± 28.26 | 102.95 ± 20.79 | 0.54 | |

| post | 73.90 ± 20.83 | 75.85 ± 16.25 | 0.33 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Grief Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) by Treatment Group and Evaluation Time a

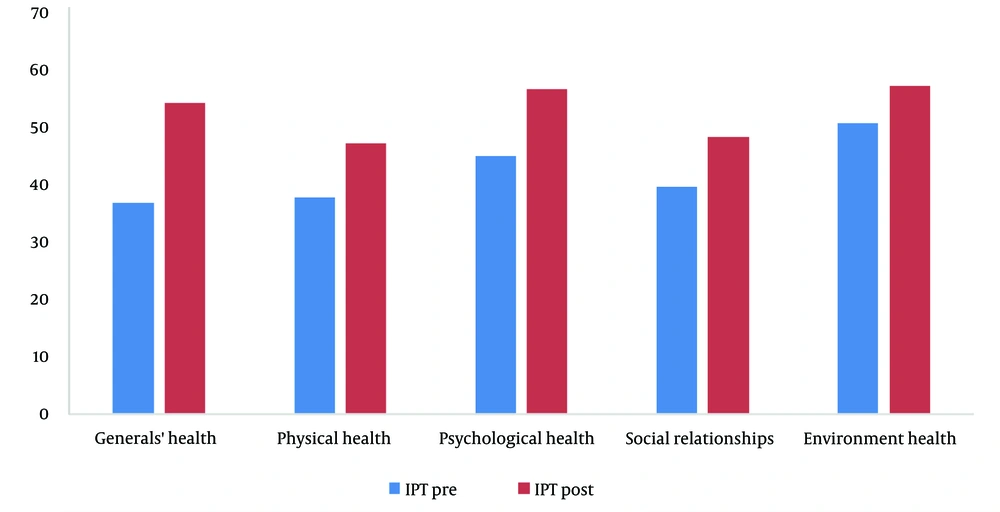

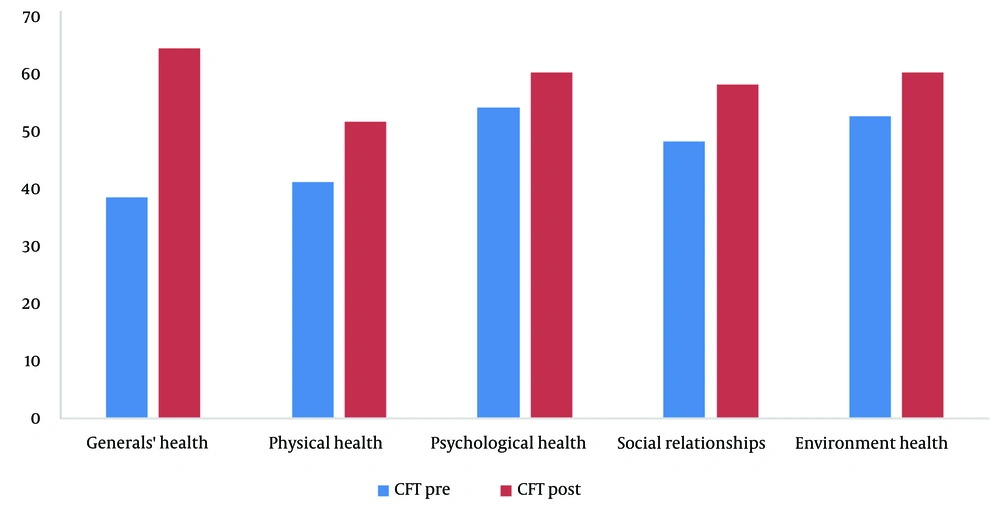

The Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) was assessed across 5 domains. The results indicated significant improvements within each treatment group separately (P < 0.001). However, when comparing the 2 groups while adjusting for the pre-test effects, there were no significant differences observed in any of the domains, including general health (P2 = 0.39), physical health (P2 = 0.92), psychological health (P2 = 0.94), social relationships (P2 = 0.98), and the environment (P2 = 0.86) (Table 3 and Figures 3-5). Overall, the quality of life, despite improvements in each treatment group, did not exhibit significant differences between the 2 treatment methods (P = 0.50).

| Variable | IPT Group (N = 20) | CFT Group (N = 20) | P1 b (ANCOVA) | P2 c (ANCOVA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generals’ health | ||||

| pre | 36.87 ± 19.64 | 36.23 ± 18.11 | 0.71 | 0.39 |

| post | 54.37 ± 22.68 | 60.62 ± 17.80 | 0.41 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Physical health | ||||

| pre | 37.85 ± 15.51 | 38.75 ± 19.32 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| post | 47.32 ± 15.41 | 48.57 ± 18.03 | 0.89 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Psychological health | ||||

| pre | 45.10 ± 21.53 | 50.83 ± 12.50 | 0.28 | 0.94 |

| post | 56.67+21.47 | 56.67 ± 12.04 | 0.54 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | 0.001 | 0.02 | ||

| Social relationships | ||||

| pre | 39.58 ± 22.27 | 45.41 ± 27.76 | 0.40 | 0.98 |

| post | 48.33 ± 19.79 | 54.58 ± 26.96 | 0.48 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Environment health | ||||

| pre | 50.78 ± 13.74 | 49.53 ± 15.55 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| post | 57.18 ± 15.01 | 56.71 ± 14.63 | 0.84 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Total | ||||

| pre | 210.20 ± 61.78 | 220.76 ± 64.55 | 0.67 | 0.50 |

| post | 252.42 ± 69.73 | 277.15 ± 60.25 | 0.41 | |

| P3 (paired t-test) | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL) by Treatment Group and Evaluation Time a

5. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effects of IPT and CFT on grief in patients bereaved by the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that individuals in both treatment groups showed improvements on both the GEQ and WHOQOL questionnaires, but our data did not reveal a significant difference between the 2 treatment strategies.

Numerous randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of IPT in the treatment of depression. IPT focuses on addressing stressful life events, such as bereavement, interpersonal disputes, life changes, social isolation, or deficits associated with the onset, worsening, or continuation of the current illness. It aims to alleviate symptoms and assist patients in connecting with social support services to enhance the quality of their relationships (15-19). Building on these findings, we proposed the use of IPT to treat grieving patients, and our results indicate that IPT can indeed be a valuable treatment strategy for individuals grieving due to COVID-19.

A similar study conducted in 2022, titled “Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Bereavement-Related Major Depressive Disorder in Japan: A Systematic Case Report,” evaluated the effectiveness of IPT on grief. The severity of MDD in their patients consistently decreased, functional disability gradually improved from the beginning until the 3-month follow-up, and interpersonal relationships with various individuals underwent positive changes following IPT. The authors concluded that IPT for bereavement-related MDD has the potential to be an effective treatment (20). The effectiveness of IPT in addressing grief was further supported by another study, consistent with our results (21). Additionally, a case report study in 2023 also yielded similar outcomes (22).

As mentioned earlier, a bereaved individual must navigate a world without their deceased loved one and seek new ways to find solace. Therefore, the focus and techniques employed in CFT, which aim to activate the calming system, may be particularly valuable for the bereaved population coping with the permanent loss of a loved one. Given that bereaved individuals often feel abandoned and isolated after a loss, group grief therapy can be especially beneficial, as it allows patients to recognize that they are not alone in their suffering (23). Our results support CFT as an effective treatment strategy for patients experiencing grief.

However, it is important to acknowledge several limitations in our study. The conclusion drawn here may not be consistent with the findings of all studies. For example, Johannsen et al. reported that group-based CFT was not efficacious in reducing prolonged grief symptoms in adults (10). One limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size. Another limitation could be the short follow-up period. Additionally, the web-based nature of our study may have presented communication challenges with patients.

In this study, we assessed the impact of IPT and CFT on grief among patients who had experienced the loss of loved ones due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of our study show that both IPT and CFT led to improvements in the quality of life and grief experience of all participants. However, we did not observe a significant difference between the 2 treatment strategies. It is important to note that this lack of significant difference may be due to our study’s limitations, such as the relatively small sample size. We recommend conducting further research with larger sample sizes to gain a more comprehensive understanding of these treatment approaches.