1. Introduction

Illicit alcohol products, particularly those adulterated with harmful substances like methanol, pose a significant health challenge (1). Methanol can cause severe and potentially fatal toxicity through metabolic acidosis (2). The exact mechanism of methanol-induced neurotoxicity remains unclear. It is hypothesized that injury to the central nervous system (CNS) may result from formic acid-induced hypoxia (3). It is well-established that an increase in the quantity of formic acid within the CNS can cause detrimental effects on the optic nerve and irreversible damage to all bodily organs (4). Despite advancements in diagnosing and treating methanol intoxication, its morbidity and mortality rates continue to be significant (3).

Over the past twenty years, cases of methanol-induced poisoning have been reported in low-income and Islamic countries, including Iran, where consumption of alcohol containing methanol has been implicated (5). Globally, alcohol use disorder caused 2.1 deaths per 100,000 people in 2019, while in Iran, the death rate due to alcohol use disorder was estimated at 0.28 per 100,000 people in the same year (6). Iran is a Middle Eastern country with a rich Islamic heritage and, according to the 2016 census, has a population exceeding 80 million, predominantly composed of young people spread across 31 provinces (7, 8).

In Iran, as in other Islamic countries, alcohol consumption is illegal due to cultural and religious beliefs (9). Consequently, population-based information on alcohol use is limited (6). Alcoholic beverages are made available to consumers through smuggling, the black market, or home production (9).

The emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) outbreak in December 2019 has led to unprecedented changes in our daily lives, significantly impacting both physical and mental health (10-12). The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended preventative measures and a healthy lifestyle with an effective immune system as means to combat and protect against this infection. One of the key recommendations from the WHO is the use of either soap or a 60% alcohol-based disinfectant for hand sanitation (13).

Iran has been one of the countries most severely affected by the rapid spread of COVID-19. In response, the country has adopted various measures to curb the pandemic, including the widespread use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers (14). However, the spread of misinformation on social media, including recommendations to consume alcoholic beverages or gargle with them to disinfect the mouth and prevent the virus, alongside suggestions to use household cleaning agents and disinfectants, has led to excessive exposure to harmful substances (15). The illegal status of alcohol production, purchase, and sale in Iran has resulted in many citizens suffering from methanol alcohol intoxication and fatalities due to consumption of illicitly produced alcoholic beverages (16).

In large provinces like Fars, located in southern Iran, the mortality rate from methanol poisoning has exceeded that from COVID-19. Several studies have suggested various reasons for this phenomenon, including the faster lethal potential of alcohol poisoning compared to COVID-19 (17).

Legal, religious, and political constraints have limited the availability of evidence-based information on alcohol consumption in certain communities within Iran, despite numerous reports of its widespread use. The increased availability of alcohol through hand sanitizers, along with illegal alcohol production and the mistaken belief that consuming alcohol can protect against COVID-19, have led to mass methanol poisoning.

2. Objectives

Given the rise in intoxication and fatalities due to methanol consumption during the pandemic, this systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive examination of methanol toxicity during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

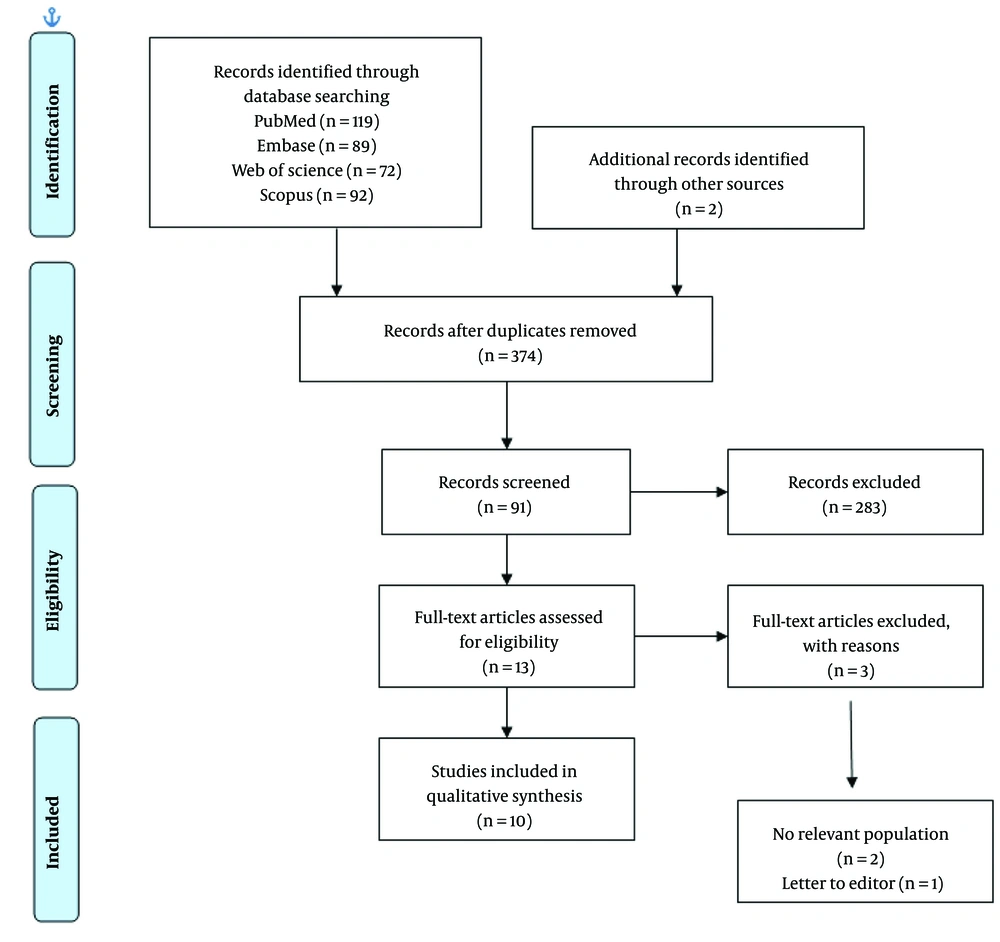

This study was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews, with the registration number ID = CRD42023426679 (18). The search for sources was carried out in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus, as well as in the Iranian databases Magiran, Iran Doc, and SID, spanning from December 29, 2019, to November 16, 2022. A detailed database search strategy is provided in the supporting information section (Supporting Appendix 1 in the Supplementary file). Additionally, the search in the PubMed database was updated until February 14, 2024. To develop the database search strategy, we combined the term “COVID-19” with terms related to “alcohol poisoning”.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies included in this systematic review met the following eligibility criteria: Cross-sectional, retrospective, and prospective cohort studies that examined the prevalence of alcohol-related intoxication and its complications during the COVID-19 period in Iran, and studies published in English or Farsi. We excluded letters to the editor, editorials and correspondence, comments and perspectives, case reports, and review articles. The initial search and screening of relevant articles were conducted independently by two of the authors, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion and at the discretion of a third author. After removing duplicates, the full texts were assessed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, the reference lists of the final studies were manually searched.

3.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction forms were utilized to record key characteristics of the studies, including the name of the first author, country, sample size, reason for consumption, gender, complications, and main findings. Two reviewers, MT-M and ZB, independently extracted the data.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Two researchers, MT-M and ZB, involved in this study independently evaluated the quality of the incorporated research papers using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal instrument. After this evaluation, the studies were summarized descriptively. We then proceeded with an in-depth analysis of the outcomes through qualitative synthesis. The critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies, developed by JBI, was used to assess the potential for bias in the included studies (19). This checklist contains nine questions categorized into four possible responses: Affirmative, negative, ambiguous, and irrelevant (due to insufficient data). An affirmative answer is scored as 1, while a negative response receives a score of 0, allowing for a total quality score ranging from 0 to 9. The total score for each study is then expressed as a percentage.

4. Results

4.1. Included Studies

A comprehensive search across multiple databases yielded 340 studies, with the distribution as follows: PubMed (n = 85), Embase (n = 89), Web of Science (n = 72), Scopus (n = 92), and other sources (n = 2). After removing duplicates, 90 studies were analyzed based on their titles and abstracts. From these, 13 studies were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria; a meticulous review of the full texts of these articles led to the conclusion that only 9 studies met all inclusion criteria. These nine were ultimately chosen for this systematic review. Detailed search results, selection processes, and reasons for study exclusion are illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Ultimately, ten studies were selected for inclusion in this review. Of these, two focused on alcohol consumption and the remaining eight specifically examined methanol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among these, three were multicenter studies (15, 20, 21), while the others were conducted at single centers. Geographic distribution of the studies included three conducted in Tehran (2, 3, 22), two in Shiraz (23, 24), and two in Yazd (25). The information extracted from these studies is summarized in Table 1. Given that most studies were carried out in the same centers during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a potential for overlapping information.

| Authors | Year of Publication | Title | Patients (n)/ Death | Male/Female | Age/Period | Study Design/City | Reason for Consumption | Sequel/Toxic Level | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahdavi et al. (21) | 2022 | A cross‑sectional multicenter linkage study of hospital admissions and mortality due to methanol poisoning in Iranian adults during the COVID‑19 pandemic | 795/84 | M: 711 (89.43%) F: 77 (9.68%) | Mean: 32 years (range 19 - 91)/from February until June 2020 | Cross‑sectional/ multicenter (Hamedan, Isfahan, Khorasan Razavi, Khuzestan, Mazandaran, Qazvin, Tehran, West Azerbaijan and Yazd) | For motives: 82.1% for prevention of cure COVID-19 infection: 3.1% | Visual disturbances/serum methanol level of 6.25 mmol/L (20 mg/dL) or higher | 1. Older patients involved more to fatal outcome than younger patients; 2. 3.1% of methanol poisoning in the first 4 months’ post COVID-19 in Iran |

| Dehghan et al. (25) | 2022 | A survey of alcohol poisoning and disinfectants cases in patients referred to hospitals in Yazd province during the COVID-19 epidemic (first wave of the disease) | 101/NA | M: 89 (88.1%) F: 12 (11.9%) | Mean: 26.07 ± 7.33 years (15 - 53)/beginning of February 2019 until May 15, 2019 | Descriptive and analytical/Yazd | For gaining happiness and joy: 47% | Occurrence of eye symptoms/estimated average alcohol consumption 273.07 ± 192.97 CC | 1. Complication free recovery: 59.4%; 2. improvement with vision problems: 12.9% other cases: 22.8% |

| Hadeiy et al. (22) | 2022 | An interrupted time series analysis of hospital admissions due to alcohol intoxication during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Tehran, Iran | 1687/127 | M: 1360 (80.6%) F: 327 (19.4%) | Mean: 31.58 ± 13.76 (range: 1 - 87) years/from February 23rd, 2019 to February 22nd, 2021 | Retrospective cross-sectional/Loghman-Hakim Hospital in Tehran | Coping behavior to the elevated anxiety | Methanol level > 6.25 mmoL/L (20 mg/dL) and ethanol level higher than 50 mg/dL | 1. A sharp rise in methanol poisoning in the first 3 months following the COVID-19; 2. High mortality in the total population and specifically among adolescents. |

| Simani et al. (3) | 2022 | The outbreak of methanol intoxication during COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence of brain lesions and its predisposing factors | 516 (40 patients under (CT) scan)/82 | M: 34 (85%) F: 6 (15%) females | Mean: 40.6 ± 13.5/March and April of 2020 | Retrospectivestudy/university-affiliated hospital’s toxicology center Tehran | History of alcohol ingestion | ICH and brain edema/methanol toxiclevel (more than 20 mg/dL or 6.2 mmol/L) | 1. Index of mortality in methanol toxicity included: Putaminal or subcortical white matter hemorrhage, brain edema; 2. Brain necrosis was significantly higher in the non-survival group; 3. The mortality rate in chronic alcohol consumption was lower than the patients who drank alcohol for the first time |

| Estedlal et al. (24) | 2021 | Temperament and character of patients with alcohol toxicity during COVID-19 pandemic | 390 total (135 from emergency room and 255 from general population)/ NA | M: 216 (55.38%), F: 174(44.61%) | Mean:32.43 ± 10.81 years/March 2020 | Cross-section study/Shiraz | Prevent COVID-19: 15% habit and recreational consumption of alcohol: 48.1% recreational consumption of alcohol: 36.8% | NA/82 cases (60.7%) more than once a week, 31 cases (23.0%) at most three times a month and 22 cases (16.3%) at most 6 times a year | Personality disorders: 60.7% cases more than once a week, more three times of drinking per month: 23.0%, more six times of drinking per year: 16.3%, increased consumption during COVID pandemic: 26.5%, no significant change in consumption: 68.1%, decreased consumption: 5.3% |

| Mahdavi et al. (15) | 2021 | COVID-19 pandemic and methanol poisoning outbreak in Iranian children and adolescents: A data linkage study | 172/22 | M: 112(65.11%) F: 60 (34.88%) | Mean: 0 to 18 years/February 23 to June 22, 2020 | Retrospective data linkage study/nine toxicology referral centers) Tehran, Isfahan, Mashhad, Qazvin, Ahvaz | For recreational purposes and/or hand sanitizers | Gastrointestinal symptoms or visual disturbances/the median [IQR] levels were 0.27 [0.02, 0.92] (range: 0 to 6.36) mmol/L methanol and 1.95 [1.52, 11.50] (range: 0.65 to 37.97) mmol/L EtOH. | The rate of pediatric exposure from ingestion of alcoholic beverages and hand sanitizers was significantly increased during the first 4 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran |

| Zamani et al. (20) | 2021 | Prevalence of clinical and radiologic features in methanol poisoned patients with and without COVID-19 infection | 356/59 (16.6%) | M: 328 (89.9%) F: 28 (10.1%) | Mean:32.76 ± 10.61 (range 15 - 72)/March and April, 2020 | Cross-sectional study/Shiraz Hospitals (Faghihi and Namazi) | Participants used alcohol regularly at least once a week (44.7%), others used alcohol infrequently or for the first time | Blindness and impaired level of consciousness/methanol toxicity, PH < 7 | Patients with concurrent methanol poisoning and COVID-19 have higher urea level is more common |

| Shadnia et al. (2) | 2022 | Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who died of methanol toxicity during COVID 19 outbreak in Loghman-e-Hakim Hospital, Tehran | 80 death | M: 68 (85%) F: 12 (15%) | Male age (42.17±13.2) female age (35.5±8.3)/March to April 2020 | Cross-sectional study/Loghman-Hakim Hospital (Tehran) | Prevention of COVID-19 | Profound metabolic acidosis/men's blood methanol levels 19.96 ± 9.7 mg/dL, blood methanol levels in women 17.77 ± 8 mg/dL | ALT, AST and PT (indicator of liver damage) were seen in most patients. Although the men were significantly more than women, there was no difference between men and women in the measured factors |

| Nikoo et al. (23) | 2020 | Electrocardiographic findings of methanol toxicity: A cross-sectional study of 356 case in Iran | 356/59 (16.6%) | M: 328 (89.9%) F: 28 (10.1%) | Mean:32.76 ± 10.61 (range 15 - 72) /March and April, 2020 | Cross-sectional study/Shiraz Hospitals (Faghihi and Namazi) | Protective and thera eutic role of alcohol consumption for COVID-19 | Blindness and impaired level of consciousness/methanol toxicity, PH < 7 | 1. Sinus rhythm was observed in 95.8%. 2. The most common ECG findings: J point elevation (68.8%), presence of U wave (59.2%), QTc prolongation (M: 53.2% and F: 28.6%), fragmented QRS (33.7%). |

| Esmaeilian et al. (26) | 2023 | Methanol poisoning during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Iran: A retrospective cross‐sectional study of clinical, laboratory, and brain imaging characteristics and outcomes | 306/60 (19.9%) | M: 286 F:34 | Mean 32.10 ± 9.9 years (range 15 to 72) March and April 2020 | A retrospective cross‐sectional study/Shiraz Hospitals (Faghihi and Namazi) | A positive history of methanol ingestion | 223 patients, accounting for 75.9% of the sample, exhibited symptoms of blindness | 1. There was a significant difference between normal and abnormal persons (in renal failure, GCS, PH, PaO2, PaCO2, HCO3, potassium and blood sugar). 2. Putamen hypodensity was 11.11% of cases in imaging finding |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; NR, not reported; AVB, atrioventricular conduction block; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; PT, prothrombin; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

4.2. Risk of Bias Within the Studies

Among the 10 studies evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute tool, the quality scores were as follows: Four studies scored 8/10 (88.88%), indicating a low risk of bias; three studies scored 8/10 (80%), indicating a moderate risk of bias; one study scored 7/10 (70%), also indicating a moderate risk of bias; one study scored 6/10 (60%), indicating a moderate risk of bias; and one study scored 4/10 (40%), indicating a high risk of bias. The risk of bias was categorized based on the total score (percentage): Scores between 20% and 50% indicated a high risk of bias; scores between 50% and 80% indicated a moderate risk of bias; and scores between 80% and 100% indicated a low risk of bias (Table 2).

| Authors | Year | 1 a | 2 b | 3 c | 4 d | 5 e | 6 f | 7 g | 8 h | 9 i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estedlal et al. (24) | 2021 | N | UC | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | UC |

| Simani et al. (3) | 2022 | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | UC | UC | UC |

| Dehghan et al. (25) | 2022 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Zamani et al. (20) | 2021 | N | UC | N | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | UC |

| Hadeiy et al. (22) | 2022 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nikoo et al. (23) | 2020 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shadnia et al. (2) | 2022 | N | Y | N | Y | UC | Y | UC | Y | Y |

| Mahdavi et al. (15) | 2021 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | UC | Y | Y | Y |

| Mahdavi et al. (21) | 2022 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Esmaeilian et al. (26) | 2023 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| The percentage of “yes” scores | 40% | 80% | 80% | 90% | 60% | 90% | 70% | 90% | 80% |

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; UC, unclear; NA, not applicable.

a Was the sample representative of the target population?

b Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way?

c Was the sample size adequate?

d Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail?

e Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample?

f Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition?

g Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants?

h Was there appropriate statistical analysis?

i Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?

4.3. Alcohol (Ethanol) Consumption During COVID-19

A survey conducted in Yazd province and a cross-sectional study in Shiraz by Dehghan et al. and Estedlal et al. evaluated alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic (24, 25). The studies did not report the levels of alcohol intoxication or deaths due to alcohol consumption. In total, 236 individuals reported alcohol consumption: 110 in Dehghan et al.’s study (25) and 135 in Estedlal et al.’s study (24). The mean age was 26.07 ± 7.33 in Dehghan et al.’s study and 32.43 ± 10.81 in Estedlal et al.’s study. The number of male consumers was higher than female consumers in both studies. Dehghan et al. reported a male-to-female ratio of 7.4, while Estedlal et al. reported a ratio of 1.24, indicating a higher number of female users in Shiraz than in Yazd province.

Dehghan et al. found that 46.5% of participants had a history of opium use and 51.5% had a history of alcohol use. Among these, 24.7% used alcohol to prevent COVID-19 and 47.5% consumed it for happiness (25). On the other hand, Estedlal et al. found that among 390 individuals, 15% used alcohol to cope with COVID-19, 48% as a habit, and 36.7% recreationally. They also noted that the rate of alcohol toxicity was 6.45 times higher in young men than in females. In their study, individuals in the alcohol consumption toxicity group exhibited higher scores in mood, novelty-seeking, and self-exaltation, and lower reward-dependence scores compared to the normal population (24). In Dehghan et al.’s study, 59.4% of the participants had a complication-free recovery, and 12.9% showed improvement in vision problems (25).

4.4. Methanol Consumption During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Seven studies focused on methanol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic (2, 3, 15, 20-23). Methanol levels above 6.24 mmol/L (20.4 mg/dL) were identified as the threshold for toxicity in five of these studies (3, 15, 20-22). One study also noted ethanol levels higher than 50 mg/dL (22). At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hadeiy et al. compared the prevalence of alcohol poisoning in Iran from one year before to one year after the pandemic began. They reported that of the 2483 patients admitted, 493 were females (pre-COVID: 166, during COVID: 327) and 1990 were males (pre-COVID: 630, during COVID: 1360), with both genders showing a significant increase in methanol toxicity during the pandemic compared to pre-COVID (females: 138 and males: 627) (22). Across all studies, males experienced higher rates of methanol toxicity than females during the pandemic.

In Hadeiy et al.’s study, the incidence of alcohol intoxication increased for both children (57 vs 17) and adolescents (246 vs 183) comparing periods before and during the pandemic. The studies by Hadeiy et al., (22) Simani et al., (3) and Mahdavi et al. (21) reported that the mortality rate was significantly higher during the pandemic (3). Additionally, first-time alcohol users had a higher death rate compared to chronic drinkers (3). In Nikoo et al.’s study, the mortality rate was 16.6% (59 persons) (23).

Mahdavi et al.’s study highlighted geographic and age-related variations in mortality rates. The lowest mortality rates were observed among individuals aged 20 to 24, whereas those aged 40 to 44 had the highest mortality rates. The capital city, Tehran, reported the highest number of referrals and mortalities (21). However, when adjusted for population size, Yazd province had the highest number of referrals among males aged 25 to 30 years, at a rate of 25.49 per 100,000 individuals (4). Yazd and Khorasan Razavi provinces reported a significantly lower mortality rate of 0.9% compared to an average of 10.6% in other provinces (21).

They also confirmed a 13.76% increase in the rate of alcohol intoxication in the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, they noted that methanol toxicity was higher than ethanol toxicity during this period (22).

Simani et al. reported on 40 patients who underwent a spiral brain computed tomography (CT) scan. The findings showed higher incidences of brain necrosis (P = 0.001), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (P = 0.004), and brain edema (P = 0.002) in those who did not survive (3). Simani et al. also assessed consciousness disorders using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (3), a tool designed to objectively describe the level of consciousness impairment in patients with acute medical and trauma conditions. The GCS is divided into three parameters: E for eye response, V for verbal response, and M for motor response, with total scores ranging from 3 to 15, where 3 indicates the deepest level of coma and 15 represents normal consciousness. The GCS and its components were detailed by Jain and Iverson (27).

The results of Simani et al.'s study revealed that the non-survival group had a significantly low GCS average of 4.54 ± 1.56 (P < 0.001), demonstrating an inverse relationship between GCS levels and mortality rate (P = 0.001). In contrast, Mahdavi et al.'s (21) study reported that 29 survivors had a GCS score greater than 8. Their findings suggested that a GCS score of 9 or less, age over 31 years, and being from any province except East Azerbaijan (with a sequelae rate of 11.4% and an average sequelae rate of 19.6%) were predictors of sequelae at discharge. They found no significant difference in liver enzyme levels between the non-survival and survival groups (3).

Mahdavi et al. also noted that hospitalization rates due to alcohol (both ethanol and methanol) consumption significantly increased in 2020 (n = 375) compared to 2019 (n = 202). During the COVID-19 pandemic, poisoning from hand sanitizers was more common among patients aged ≤ 15 years than from alcoholic drinks. There was a 6.7-fold increase in alcohol consumption among 15-18-year-olds compared to other age groups, and fatalities among this age group increased sevenfold. Of 172 patients who consumed alcoholic beverages and used hand sanitizer, 22 died from poisoning (15).

In another study, Mahdavi et al. sought to evaluate the epidemiology of methanol poisoning in Iran during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing particularly on hospitalization and mortality rates. Of the 795 patients hospitalized due to methanol poisoning, 84 died. The age range of these patients was 19 - 91 years. A majority, 82.1%, typically used alcohol for recreational purposes, and 3.1% of all patients had consumed alcoholic hand sanitizers to prevent COVID-19 infection. Males were more frequently admitted due to alcohol poisoning than females (M: 718, F: 77). Survivors were notably younger than non-survivors. Similarly, patients without any sequelae were younger compared to those who experienced sequelae (21).

In East Azarbaijan province, hemodialysis was administered to patients showing symptoms of methanol poisoning. Thanks to prompt intervention, the rate of sequelae in this province was significantly lower (7.2%) compared to the average across other provinces (11.4% to 19.6%). Older patients were more susceptible to lethal outcomes and sequelae, including visual disturbances. The incidence of methanol poisoning in Iran saw a significant increase during the first four months following the onset of COVID-19 (21).

Comparing survivors with and without sequelae (n = 642), 492 out of 632 (77.8%) reported no sequelae at discharge. Neurological complications were experienced by seven out of 632 people (1.1%), and vision disorders were reported by 133 out of 632 (21.1%). Out of 795 people, 79 (9.9%) had no recorded health information (4).

In Nikoo et al.’s (23) study, 356 patients were reported, with a distribution of 328 males and 28 females. The mean age of the patients was 32.76 ± 10.61 years (10). Regular alcohol consumption at least once a week was reported by 44.7% of the patients. The majority had consumed alcohol for the first time or had only consumed small amounts. Concurrent use of other substances, such as opium, was reported by 9.5% of the patients. The mortality rate stood at 16.6% (59 persons), and 251 individuals (70.5%) experienced visual impairment, making it the most common clinical side effect (23). A significant majority of the study population, 95.8%, exhibited sinus rhythm, while a minority of 4.2% displayed alternative cardiac rhythms, including atrial fibrillation and low atrial rhythm. There was a high association between severe acidosis (pH < 7) and conditions like QTc > 500, atrioventricular block (P = 0.045), sinus tachycardia, and ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Changes in R wave progression, low voltage QRS, T slope, and J elevation were not associated with severe acidosis (23).

The study also highlighted a significant gender disparity: Men comprised almost three times the number of women (85% vs. 15%). The mean and standard deviation of age were 42.17 ± 13.2 years for men and 35.5 ± 8.3 years for women. The number of men who died before dialysis was four times that of women (32% vs. 8%, respectively). High metabolic acidosis was common among most cases (2). There were no significant differences between men and women in terms of time between substance intake and hospital arrival, number of dialysis sessions, pulse rate, respiratory rate, loss of consciousness, seizures, acute kidney injury, brain CT, and ICH (2).

In the patients studied, blood sugar, liver function tests, white blood cell count (WBC), and serum potassium levels were generally higher than average, though no significant gender differences were observed (11). While blood sugar (BS) and platelet (PLT) levels were higher in women than in men, these differences were not statistically significant (2).

Zamani et al. conducted a study that included 62 patients with confirmed methanol poisoning. The majority of these patients had consumed alcoholic beverages, and a small percentage had used alcoholic sanitizers (20). Of these, 26 patients (41.9%) reported using alcohol for recreational purposes. Thirty-three cases (53.2%) did not specify their intent behind drinking. Notably, 65.9% of the cases had a history of organized alcohol consumption, while 34.1% did not report any such history. The majority of those who survived had a history of regular alcohol consumption, while a smaller minority did not have such a history, and very few used alcohol as a disinfectant against COVID-19 (20).

The study by Zamani et al. found that out of 62 patients with methanol poisoning, 39 survived, and nine of these had COVID-19. Most of the COVID-19 infections were detected through spiral chest CT scans, with a minority confirmed by PCR, and only four of the nine patients with COVID-19 survived (20). However, the mortality rates between patients with or without COVID-19 did not show significant differences. Among the COVID-19 affected patients, seven had a history of consistent alcohol consumption, while 37.7% (20 out of 53) of the non-infected cases had a similar history. Statistical analysis confirmed a significant association between COVID-19 and previous alcohol consumption, yet no significant differences were observed in brain CT findings between patients with or without COVID-19 (20).

Out of the 56 patients who underwent chest CT scans, 36 (69.2%) had normal findings, whereas 20 (30.8%) showed abnormalities, with 16.1% of these changes attributed to COVID-19 infection. Additionally, of the 38 patients who underwent brain CT scans, 30 (78.9%) exhibited abnormal findings (20). Research supports the use of brain imaging as a crucial tool in identifying and managing patients with methanol poisoning. It is recommended that patients displaying severe acidosis and reduced levels of GCS, pH, and oxygen saturation, coupled with elevated glucose levels, should be prioritized for a brain CT scan (26). This approach helps in better understanding the extent of neurological damage and guiding appropriate treatment interventions.

5. Discussion

In this systematic review, we examined the prevalence of alcohol poisoning (both methanol and ethanol) and its complications during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Due to the prohibition of alcohol consumption and the availability of potentially methanol-contaminated household alcohol, incidents of methanol poisoning have risen throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran (23). Our findings indicate that the rate of methanol poisoning has notably increased during the pandemic. The review ultimately included ten studies, eight of which focused on methanol poisoning and two on ethanol poisoning, selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

A previous study conducted in 2018 found that 768 individuals in Iran were poisoned from September 7 to October 8, 2018, by consuming illicit alcohol tainted with methanol, resulting in 76 fatalities. Global studies have also indicated that alcohol consumption increased during the quarantine period compared to before (5, 28). Recent research has shown that methanol poisonings similarly surged in Turkey and Azerbaijan during the COVID-19 pandemic as individuals attempted to protect themselves from the virus by consuming alcohol (29). In this study, a total of 4,167 individuals were hospitalized due to methanol poisoning across eight provinces, with 546 patients succumbing to the poisoning. The data revealed that Tehran, Yazd, and Shiraz were the regions most affected by alcohol poisoning.

The results of four studies included in this review indicated that the most commonly reported clinical manifestations of methanol poisoning were vision impairment and blindness, with severity depending on the dose. A study conducted by Mousavi Roknabadi et al., prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in Shiraz, Iran, reported that 75% of individuals with acute methanol poisoning experienced visual disturbances (30). Similarly, a study in Saudi Arabia in 2015 by Galvez-Ruiz et al. noted that methanol poisoning could cause vision loss within 12 to 48 hours due to severe, painless, bilateral damage to the optic nerve (31). In Yemen, a 2021 study found that 40% of patients with alcohol poisoning suffered long-term vision consequences, with 8% resulting in blindness (32). Additionally, Esmaeilian et al. demonstrated a significant correlation between being over the age of thirty and a history of blindness (75.9%) with a decreased chance of patient survival. Notably, these factors were not associated with abnormal findings in brain CT scans (26). Our findings align with these previous studies, highlighting consistent patterns of clinical outcomes following methanol poisoning.

Additionally, three studies reported cerebral edema and hemorrhage, digestive disorders, and metabolic acidosis as the most common complications of poisoning from methanol-contaminated alcohol. These clinical symptoms are consistent with findings from previous research. In 2023, Decker et al. found that severe cases of methanol poisoning could lead to intracranial hemorrhage and even death (33). Aisa and Ballut in a 2016 study, noted that cerebral hemorrhage is a rare but aggressive complication of methanol poisoning, emphasizing the need for vigilant treatment approaches (34). In 2022, Gautam et al. conducted a study in India where all 33 patients included had digestive disorders, and 90% exhibited metabolic acidosis (35). These findings underscore that methanol poisoning remains a critical public health issue in developing countries, and prompt medical intervention is crucial for reducing mortality rates.

The research indicates that the primary reasons for consuming alcohol containing methanol among those referred to poisoning treatment centers were (1) to prevent the spread of COVID-19; and (2) for recreational purposes. Studies have demonstrated that individuals facing significant stressors may resort to high-risk alcohol consumption patterns, such as excessive drinking (36). De Sio et al.'s 2020 study highlighted that employment is a significant determinant of health and can reduce the risk of alcohol consumption (37). Another study included in this research showed that alcohol poisoning is more prevalent among individuals with lower levels of education and economic status. Jones-Webb et al. reported in 2016 that there was a positive correlation between job loss and increased alcohol consumption (38), suggesting that the surge in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic might be linked to business closures and economic downturns, putting substantial stress on families.

Risk factors for increased alcohol consumption in Iran were identified as masculine gender, young age, and urbanization. Previous studies have noted young age and masculine gender as risk factors associated with a higher likelihood of alcohol consumption and dependence (39). The higher incidence of alcohol consumption among men might be attributed to easier access to alcohol. The relatively low prevalence of alcohol consumption among Iranian women is likely due to religious and cultural constraints; adherence to traditions is generally stronger among women, and alcohol and drug use carry a higher level of social stigma for them. However, evidence suggests that the gender gap in alcohol consumption may be narrowing among the younger generation in Iran (40). Without adequate attention to social, cultural, and religious factors, there could be a rise in the number of women consuming alcohol in the near future.

When evaluating the results of this systematic review, it's important to consider that due to the legal prohibition of alcohol consumption, fear, and social stigma in Iran, many individuals may avoid seeking medical attention. This reluctance could lead to underreporting, meaning that accurate statistics may not be available for all regions of Iran. Additionally, the studies included in this review were limited to only a few cities, which restricts the ability to generalize the findings to the entire population. It is also critical to acknowledge that timely hospital admission can enable prompt diagnosis and treatment, significantly reducing the risk of long-term complications associated with methanol poisoning.

6. Conclusions

Our results indicate that the prevalence of methanol poisoning is notably higher among young people. Therefore, an essential strategy for preventing methanol poisoning involves enhancing public awareness, particularly among the youth. This can be effectively achieved through various channels such as national media, social networks, schools, and universities. Additionally, hospitals should be viewed as safe havens for individuals affected by methanol poisoning, where healthcare professionals are committed to confidentiality and would not disclose any patient information.

However, due to the limitations in time and location of the studies, the generalizability of the findings should be approached with caution. To effectively monitor, diagnose, and manage the crisis of alcohol consumption in Iran, it is crucial to utilize all available capacities of mass media, including national television, radio, social networks, the SMS system, and even the platforms provided by Friday prayer sermons.