1. Background

Social anxiety is characterized by a persistent fear of one or more social situations where individuals are exposed to the scrutiny of others. These individuals fear behaving in a manner that could lead to embarrassment, humiliation, or negative evaluation in social contexts (1). The intensity of social anxiety is greater during adolescence than in childhood. Previous studies have shown that adolescent girls experience social phobia and social anxiety disorder more frequently than boys (2). A significant factor contributing to social anxiety in adolescent girls is that physical changes have more adverse effects on their social environments compared to boys. Girls who reach puberty earlier face more interpersonal pressure than boys (3). The development of secondary sexual characteristics in girls, such as breast development, may play a crucial role in increasing social anxiety (4).

To understand why adolescent girls avoid social contact more than boys, a key question arises: Why do physical changes in adolescent girls increase their social anxiety? Objectification theory may offer new insights into this relationship. Sexual objectification theory links a woman’s worth to her ideal physical appearance, leading to internalized self-objectification from a third-person perspective. In this context, individuals view themselves as objects that others evaluate solely based on physical appearance (5). The public nature of girls’ physical development can increase the risk of self-objectification (6), which may, in turn, heighten their social anxiety.

Cognitive models of social anxiety suggest that individuals may create a mental representation of their appearance and behavior from the perspective of an observer (i.e., the assumed audience). When this mental representation is associated with negative evaluation by the audience, individuals experience anxiety in social situations (7). One factor that appears to play a role in the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety in adolescent girls is self-worth. Self-worth is understood as a reflection of an individual’s subjective evaluation of their value in interpersonal relationships. People with low self-worth believe they have less value compared to others and find social interactions challenging, resulting in fewer social engagements (8).

Self-worth is closely related to significant changes in physical appearance during adolescence. Adolescent girls often experience lower self-worth when they perceive a discrepancy between their ideal and actual body image (9). Studies have shown that adolescents with lower self-worth tend to experience more social anxiety (10). Girls who self-objectify are more likely to exhibit lower self-worth because they strive to achieve highly unattainable ideals of female physical appearance, a result of sexual objectification (11). Several empirical studies have confirmed the relationship between self-objectification and self-worth among adult women (12).

Considering the role of physical appearance in self-worth and the effect of self-objectification on self-worth and physical appearance, another factor that may mediate the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety in adolescents is body image concern. Body image can be defined as an individual’s experience of their physical self (3). The changes occurring during adolescence are associated with concerns about physical attractiveness and cause adolescents to worry excessively about others’ evaluations of their appearance. When adolescents experience negative evaluations, they form negative body image schemas, leading to excessive worry and negative interpretations of others’ behavior (13).

Body image concerns cause adolescents to devote significant time and resources to contemplating their appearance changes. Adolescents attempt to conceal perceived appearance defects, which are largely influenced by their mental image of their body, and exhibit avoidance behavior in interpersonal situations (14). Given that adolescence is associated with significant changes in appearance, adolescents may develop distorted estimates of their physical appearance, evaluate their appearance negatively, and become susceptible to physical and social anxiety (15).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to explore the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety among adolescent girls, with a focus on the mediating roles of self-worth and body image concern. The investigation was inspired by observations that adolescent girls may experience higher levels of self-objectification (16), which could affect their self-worth and body image, potentially leading to increased symptoms of social anxiety. Given the lack of research on this topic in Iran, this study seeks to address this gap in the literature and provide a comprehensive understanding of the intricate dynamics between these psychological constructs within the Iranian context.

3. Methods

A cross-sectional study was employed as the research method. During the 2022 - 2023 academic year, the statistical population comprised all adolescent girls (upper secondary school) in Isfahan City. Cohen’s method was used to calculate the sample size (17). The calculation included an Effect Size Index of 0.20, a statistical power of 85%, four latent variables (self-objectification, self-worth, body image concern, and social anxiety), and 14 observable variables corresponding to the components of each variable. The confidence level was set at a conventional value of 0.95. Based on these parameters, the estimated sample size derived from Cohen’s method was 381 individuals. A total of 384 participants completed the research questionnaires and underwent statistical analysis.

The 384 adolescent girls were selected using a multi-stage cluster sampling method. The sampling procedure was as follows: Four regions (1, 3, 5, and 6) were selected from the nine regions of Isfahan city through simple random sampling. Three schools were then chosen from a comprehensive list of girls’ high schools in these regions. Subsequently, two classes were randomly selected from each school. In collaboration with headmasters, research questionnaires were distributed to adolescent girl students via virtual platforms such as Shad, WhatsApp, and Telegram.

The inclusion criteria for the study were: Girls aged 15 to 18 years, access to a computer or mobile phone with active internet connectivity, and membership in at least one virtual social network to receive the questionnaire link. The exclusion criteria included questionnaires with specific filling processes or those with uniform responses to all questions. In the online implementation of the questionnaires, answering all questions was a prerequisite for progressing to subsequent pages and completing the survey. Therefore, after verifying the questionnaires’ compliance with the study’s criteria, the distribution process continued until an appropriate sample size was achieved. A total of 461 adolescent girls were approached, resulting in the collection of 384 valid responses. The questionnaire distribution period extended from the beginning of November 2022 to April 2023.

3.1. Research Instruments

3.1.1. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents

La Greca and Lopez developed this scale to measure social anxiety during adolescence (18). The Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) comprises 18 items scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from "completely like me" (5) to "completely different from me" (1). La Greca and Lopez (as cited by Fatemi et al.) reported a test-retest reliability of 0.75 over an eight-week interval. In Iran, a study assessed the internal consistency of this scale using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (19). They reported values of 0.84, 0.76, and 0.77 for the components of fear of negative evaluation, social avoidance and distress in new situations, and general social avoidance and distress, respectively.

3.1.2. Self-objectification Questionnaire

Noll and Fredrickson developed this questionnaire in 1998. The Self-objectification Questionnaire (SOQ) consists of 10 items, with scores calculated based on ranking. The highest score is 10, and the lowest score is 1. The final score, ranging from -25 to 25, is obtained by subtracting competence-based values from appearance-based values. Higher scores indicate greater self-objectification, while lower scores suggest competence-based values (20). The questionnaire’s validity was assessed using Bartlett’s test, with an estimated correlation of 65.56 between questionnaire items. The reliability of the questionnaire was estimated at 0.80 using the ballad method. A study conducted in Iran reported a reliability coefficient of 0.80 using the split-half method (21).

3.1.3. Contingencies of Self-worth Scale

Crocker et al. developed this scale, which consists of 35 items rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from "completely disagree" (1) to "completely agree" (7) (22). The Contingencies of Self-worth Scale (CSWS) measures the level of self-worth and the importance individuals attribute to themselves. The scale’s creators reported a test-retest reliability of 0.75 over a three-month period (22). A study conducted in Iran involving 448 high school students reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.83 for the CSWS (23).

3.1.4. Body Image Concern Inventory

Littleton et al. designed and compiled this questionnaire, which comprises 19 items divided into two subscales: Dissatisfaction-embarrassment due to appearance and impaired functioning due to appearance concerns (24). The Body Image Concern Inventory (BICI) is scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from "never having this feeling" (1) to "always having this feeling" (5). Total scores range from 19 to 95, with higher scores indicating greater concern about body image or appearance. In Iran, a study reported a reliability coefficient of 0.95 for internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha (25). The study demonstrated convergent validity with a coefficient of 0.83, based on its correlation with the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Scale.

3.2. Procedure

The study commenced upon obtaining the necessary permissions from education officials in Isfahan city. Participant recruitment involved providing comprehensive information about the research objectives, participation conditions, and confidentiality measures. In collaboration with school administrators, links to the questionnaires were distributed via social networking platforms, including Shad, WhatsApp, and Telegram. A detailed consent form was included at the beginning of the online questionnaire to ensure ethical compliance. This form elucidated the study’s purpose, participation requirements, response guidelines, and confidentiality assurances, enabling participants to make an informed decision regarding their involvement before proceeding with the survey.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27 and AMOS version 24 software. Pearson correlation tests were employed to assess bivariate relationships among the variables of interest. Partial correlation analyses were performed to investigate the relationships between independent and dependent variables while accounting for potential mediating effects. The conceptual model was evaluated using structural equation modeling (SEM) with a covariance-based approach (CB-SEM), facilitating the simultaneous examination of complex variable relationships. The Sobel test was utilized to assess the significance of mediation effects, providing a statistical evaluation of indirect relationships within the model. This comprehensive analytical strategy allowed for a rigorous examination of the hypothesized relationships between self-objectification, self-worth, body image concern, and social anxiety in adolescent girls.

4. Results

Demographically, all respondents were female students, with 37.8% enrolled in the first level of education, 21.9% in the second level, and 40.4% in the third level. The average age of the research sample was 17.02 years, ranging from minimum of 15 to maximum of 18 years. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of main variables, including medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs), and the lowest and highest scores.

| Variables | Descriptive Statistics | Normality Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Mean (Range) | Median (IQRs) | Min-Max | Skewness | Kortosis | |

| Self-objectification | 25.7 (10 - 100) | 34 (10) | 16 - 67 | 0.384 | -0.986 |

| Self-worth | 35.0 (35 - 245) | 108 (26) | 59 - 182 | -0.452 | -0.805 |

| Body image concern | 36.0 (19 - 95) | 47 (12) | 23 - 69 | 1.11 | 1.18 |

| Social anxiety | 41.9 (18 - 90) | 49 (14) | 29 - 73 | 0.295 | -1.08 |

Table 1 demonstrated multivariate normality, a key assumption for covariance-based modeling tests, evaluated using Mardia’s coefficient. The coefficient was 4.10, indicating that the multivariate normality assumption was valid. The model was implemented and analyzed using the covariance method and AMOS software. Table 2 presents the results of the Pearson correlation test between the main variables in the form of a correlation matrix.

| Types and Variables | Control Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate correlation | ||||

| Self-objectification | 1 | 1 | ||

| Self-worth | 2 | -0.39 (< 0.001) | 1 | |

| Body image concern | 3 | 0.23 (< 0.001) | -0.52 (< 0.001) | 1 |

| Social anxiety | 4 | 0.28 (< 0.001) | -0.63 (< 0.001) | 0.45 (< 0.001) |

| Partial correlation | ||||

| Body image concern | Self-worth | 0.19 (0.002) | ||

| Body image concern | 0.26 (< 0.001) |

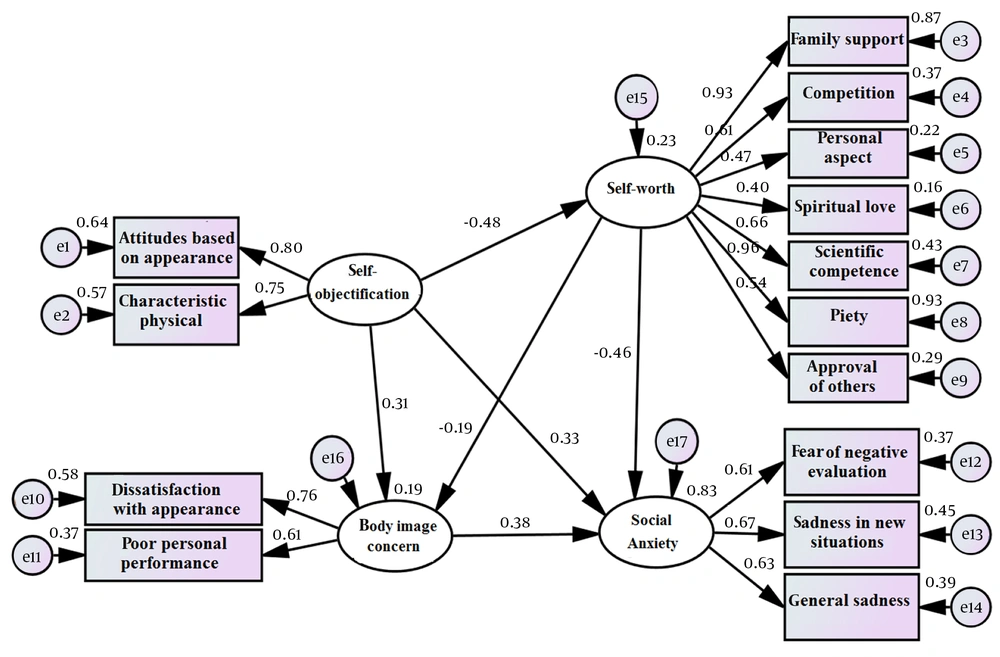

Table 2 indicates that self-objectification, self-worth, and body image concern were all significantly related to social anxiety (P < 0.05). The strongest correlation with social anxiety was observed for self-worth, with a correlation coefficient of -0.63, followed by body image concern, which had a coefficient of 0.45. Results from the partial correlation test demonstrated that the intensity of the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety decreased slightly after controlling for self-worth and body image concern variables, but it remained statistically significant (P < 0.05). Figure 1 illustrates the model with standardized coefficients.

Figure 1 indicated that the strongest effect in the model was the impact of self-objectification on self-worth, with an effect coefficient of -0.48, followed by the effect of self-worth on social anxiety, which had a coefficient of -0.46. The intensity of self-objectification’s effect on self-worth, body image concern, and social anxiety ranged from 0.3 to 0.5, indicating moderate effect sizes. The coefficient of determination for the dependent variable, social anxiety, was 0.83. Self-objectification, self-worth, and body image concern collectively explained 83% of the variance in social anxiety. For all variables, the intensity of the relationship between components, observable variables, and latent constructs exceeded 0.40, indicating appropriate model validity. Table 3 displays the results of the Sobel test, which investigated the mediating roles of self-worth and body image concern in the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety.

| Values | R2 | GFI | IFI | AGFI | PGFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | Chi-s/ df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal values | < 0.33 | ≥ 0.90 | ≥ 0.90 | ≥ 0.90 | ≥ 0.70 | ≥ 0.90 | ≥ 0.90 | ≤ 0.08 | 0.5 - 1.0 |

| Stated values | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.072 | 2.64 |

Table 3 revealed that none of the fit indices exhibited weak values, and all items were within acceptable ranges. The findings showed that the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) was 0.93, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.94, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.92, all exceeding the standard threshold of 0.90, indicating an appropriate model fit. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) fit index was 0.072, below the criterion of 0.08, further supporting an appropriate model fit. The coefficient of determination for the dependent variable, social anxiety, was 0.83, which exceeded the average value of 0.33, indicating the model’s strong explanatory power. Based on these results, self-objectification, self-worth, and body image concern explained 83% of the variance in the dependent variable, social anxiety, demonstrating the model’s high explanatory power. Table 4 reports the direct effects in the model, providing standardized coefficients (impact intensity) as well as t and P statistics (significance of relationships).

| Paths | Standardized Coefficient | Unstandardized Coefficient | SD | t-Value | P-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-objectification → social anxiety | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.082 | 3.83 | < 0.001 | Accepted |

| Self-objectification → self-worth | -0.48 | -0.64 | 0.100 | -6.41 | < 0.001 | Accepted |

| Self-objectification → body image concern | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.069 | 2.92 | < 0.003 | Accepted |

| Self-worth → social anxiety | -0.46 | -0.33 | 0.054 | -6.04 | < 0.001 | Accepted |

| Body image concern → social anxiety | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.132 | 4.13 | < 0.001 | Accepted |

| Self-worth → body image concern | -0.19 | -0.09 | 0.044 | -2.12 | 0.034 | Accepted |

The effect direction was positive, indicating that an increase in narcissism was associated with an increase in social anxiety (effect intensity of 0.33) and body image concern (effect intensity of 0.31). Additionally, an increase in body image concern was associated with an increase in social anxiety (effect intensity of 0.38). The effects of narcissism on self-worth (effect intensity of -0.48), social anxiety (effect intensity of -0.46), and body image concern (effect intensity of -0.19) were confirmed (P < 0.05). The direction of these effects was negative, demonstrating that an increase in narcissism was associated with a decrease in self-worth, while an increase in self-worth was associated with a decrease in social anxiety and body image concern.

The results of the Sobel test (Table 5) confirmed that variables of self-worth and body image concern play significant mediating roles (P < 0.05).

| Paths | Unstandardized Coefficient | SD | Sobel Test | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Value | P | ||||

| Self-objectification → self-worth | -0.64 | 0.100 | 4.42 | < 0.001 | Accepted |

| Self-worth → social anxiety | -0.33 | 0.054 | |||

| Self-objectification → body image concern | 0.20 | 0.069 | 2.36 | 0.018 | Accepted |

| Body image concern → social anxiety | 0.54 | 0.132 | |||

5. Discussion

This research investigated the mediating role of self-worth and body image concern in the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety among adolescent girls. The results demonstrated that self-worth and body image concerns play significant mediating roles between self-objectification and social anxiety. These findings align with previous research (15, 20, 26). To explain these findings, one can posit that adolescent changes are associated with concerns about physical attractiveness and body image, causing adolescents to be highly anxious about others’ evaluations of their appearance. Given that sexual objectification establishes difficult-to-achieve ideal body standards and evaluates women based on their physical appearance (27), it engenders higher levels of self-objectification in women. This phenomenon likely has a substantial impact on reducing women’s sense of self-worth (22), which may result in a tendency to avoid social situations.

Self-objectification among girls probably leads them to imagine an unattainable ideal image for themselves, consequently feeling less self-worth. This diminished self-worth, in turn, fuels avoidance of social interactions. Girls who self-objectify may experience lower self-esteem after evaluating themselves through the lens of a critical observer, and they may ultimately avoid socializing due to feelings of unworthiness in interpersonal interactions. Objectification theory asserts that the way people regard women in interpersonal interactions and media representations contributes to the widespread objectification of women’s bodies. Consequently, women internalize this external view, engage in self-objectification, and ultimately evaluate their sense of self-worth based on their bodies.

Conversely, self-worth is considered an index of psychological adaptation and proper social functioning, which enhances overall public health, improves social behavior, and manifests its effects at various levels of individual and social life. As a result, a high sense of self-worth can counteract self-objectification and reduce social anxiety (28).

The results indicated that body image concern serves as a significant mediator between self-objectification and social anxiety. These findings corroborate the research of previous studies (26, 29). To elucidate this hypothesis, one can refer to objectification theory, which suggests that individuals may create mental representations of their appearance and behavior from an observer’s perspective (i.e., assumed). When this mental representation is associated with negative evaluation by the audience, individuals experience anxiety and fear in social situations (20). A person who experiences negative evaluation forms a negative body image schema, leading to excessive worry and negative interpretations of others’ behavior. Body image concerns cause adolescents to devote considerable time and resources to contemplating changes in their appearance. Adolescents attempt to conceal their perceived appearance defects, which are largely rooted in the mental image of their body, and exhibit avoidance behavior in interpersonal situations. These behaviors engender negative cognitive and emotional experiences regarding physical appearance and associated concerns. Due to the physical changes girls undergo during adolescence, these factors can form the basis for interpersonal distress and social anxiety in adolescent girls. Self-objectification increases the likelihood of negative evaluation of physical appearance from the observer’s perspective (13), potentially increasing social avoidance. Adolescent girls may feel less comfortable in interpersonal interactions, communicate less, and exhibit a diminished desire for social contact.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Given the correlational nature of this research, definitive conclusions about the causal order of variables cannot be drawn. The sample consisting solely of adolescent girls limits the generalizability of results to adolescent boys. The absence of paper-and-pencil questionnaires and the reliance on virtual social networks for distribution may have resulted in unequal participation conditions among participants.

To address the study’s limitations, future research should explore several key areas. It would be beneficial to include adolescent boys in similar studies, as evidence indicates that they also experience pressures related to physical ideals. This could provide a broader perspective on self-objectification and social anxiety across genders. Additionally, conducting longitudinal research could help establish more concrete evidence about how self-objectification, self-worth, body image concern, and social anxiety influence each other over time. Expanding research to diverse cultural contexts would also be valuable, as it could reveal cultural differences that impact these psychological constructs. Using a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods could offer a richer and more nuanced understanding of these phenomena, capturing aspects that might be missed by relying on a single approach.

Despite its limitations, this study contributes significantly to our understanding of the psychological mechanisms underlying social anxiety in adolescent girls. It offers a foundation for developing targeted prevention and intervention strategies to promote psychological well-being in this vulnerable population. By addressing the intricate relationships between self-objectification, self-worth, body image concern, and social anxiety, this research paves the way for more nuanced approaches to supporting adolescent mental health and fostering resilience in the face of societal pressures. These findings have important implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers working with adolescent populations. They suggest the need for interventions that focus on enhancing self-worth, promoting positive body image, and reducing self-objectification tendencies among young girls. Such interventions could potentially mitigate the development of social anxiety symptoms and foster healthier psychological development during this crucial life stage.

This study provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between self-objectification, self-worth, body image concern, and social anxiety among adolescent girls in Iran. The findings underscore the significant mediating roles of self-worth and body image concern in the relationship between self-objectification and social anxiety. These results not only corroborate existing literature but also extend our understanding of these psychological constructs within the Iranian cultural context. The study highlights how the internalization of societal standards of beauty and subsequent self-objectification can lead to diminished self-worth and increased body image concerns, ultimately contributing to heightened social anxiety among adolescent girls.