1. Context

Pregnancy worries are defined as a specific type of psychological distress experienced by a pregnant woman regarding her health, her baby's health, her body image, and delivery (1). Various biological and environmental conditions, along with changes in personal relationships, cause high levels of stress and anxiety in pregnant women (2). Concerns about the newborn’s health, pregnancy complications, pregnancy loss, and childbirth are the common sources of worries in pregnant women. Also, external stressors such as worries about money, job, housing, health, and marital relationships can interfere with the natural course of pregnancy (3).

The prevalence of prenatal depression varies from 7% - 20% in high-income countries to over 20% in middle- and low-income countries (4). Meanwhile, 16.7% - 74% of women suffer from prenatal tension and anxiety during the first trimester of pregnancy (5).

While pregnancy anxiety is a strong predictor of adverse birth and infant outcomes, the exact role of different sources of prenatal stress, depression, anxiety, and pregnancy-specific anxiety in infants’ emotional reactivity is still unclear (6). A previous study reported a relationship between prenatal anxiety and high negative emotionality in infants who received low postnatal stroking (7). A recent review identified antenatal worries and anxiety, along with a previous history of psychiatric illnesses, poor marital relationship, stressful life events, negative attitude toward pregnancy, and lack of social support, as significant risk factors for postnatal depression (8). It is, hence, essential to determine the extent and causes of pregnancy worries and anxiety.

While a national prenatal screening program for anxiety and depression is performed to measure pregnant women’s vulnerability in Australia, such formal screening procedures are not as widely used in the United States or United Kingdom (9). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Healthy Child Program in England have both emphasized the necessity of determining the effects of prenatal anxiety on women and their offspring (10). Despite the high prevalence of pregnancy worries and stress, their assessment using suitable scales has not been widely investigated in the Middle Eastern countries. This highlights the need for the evaluation of the available scales for pregnancy worries and stress.

Various tools and measures, including the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) (11) and Cambridge worry scale (CWS) (12), have been administered to examine the level of prenatal tension, stress, and worries. However, the use of these tools is associated with several problems. Most importantly, while these scales evaluate general anxiety and worries, a pregnant woman, who is not depressed and anxious due to other reasons, might be concerned about both childbirth and her unborn baby's health (13). The identification and measurement of pregnancy worries would thus require a valid and reliable scale specifically designed for pregnant women. Systematic reviews are powerful tools to summarize the existing research and provide a large body of evidence about a particular subject of interest (14). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are shortcomings in previous reviews of the available instruments for pregnancy worries and stress. In fact, although the existing reviews have presented significant information in this field, they present contradictory information. Brunton et al. reviewed the scales used to assess pregnancy-related anxiety, and Alderdice et al. provided a psychometric analysis of the existing pregnancy-specific maternal stress measures. These reviews differ from this study by construct (9, 15). Therefore, this article aimed to review the literature regarding pregnancy worries scales.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Search Strategy

In order to find the relevant studies, we searched the Cochrane database of systematic reviews (via Cochrane library), PubMed, Medline, Scopus, ISI Web of Knowledge, ScienceDirect, Psyc INFO, and Google Scholar. We used the following keywords (Mesh-terms): “pregnancy” AND (“stress” OR “anxiety” OR “worries”), “pregnancy worries scale” OR “pregnancy stress scale” OR “pregnancy anxiety scale” OR “prenatal stress scale” OR “pregnancy-related anxiety scale.” Articles were included if they were published in English during 1983 - 2016 and described an instrument to measure or screen pregnancy-related worries, stress, and anxiety.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies that used an existing instrument or developed a particular tool to investigate the presence of pregnancy-related worries and stress and/or measure their intensity were included. A wide range of studies, including published theses in Persian language, were selected.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

We excluded articles on a topic unrelated to our review or those that did not specifically focus on pregnancy-related worries, distress, anxiety, and depression. Also, studies which lacked numerical outcome data were not selected.

2.4. Study Selection

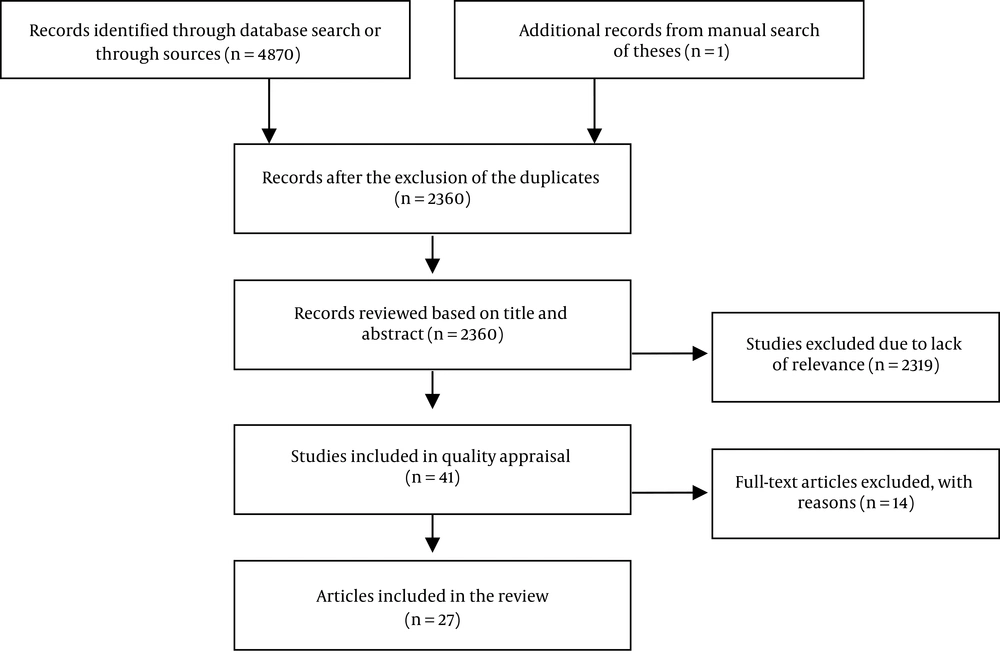

Two authors selected the eligible studies and resolved cases of disagreement through consensus. Overall, one thesis and 4870 papers were individually assessed, and the duplicates were excluded. Following the evaluation of the abstracts and titles of the remaining 2360 papers, 2319 irrelevant articles were excluded, and the full texts of the remaining 41 articles were examined. While 27 papers were found eligible, 14 papers were excluded since they did not provide specific information about the administered scales. The flow diagram of the literature review process is presented in Figure 1.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The consensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments (COSMIN) checklist with a four-point rating scale was used for the quality assessment of the selected papers. COSMIN is a standardized tool for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health measurement instruments. The checklist consists of nine boxes to evaluate nine different measurement properties including internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity, and responsiveness (16). Each box contains 5 - 18 items about the applied design and statistical methods.

2.6. Data Extraction

The selected articles were carefully reviewed, and the required data, including the author names and publication year, the name of the administered instrument, items and response format of the instrument, data about reliability and validity, and description of the instrument, were extracted and reported.

3. Results

A total of 27 different scales were used in the 27 selected studies (Table 1). While all the studies reported reliability data, test-retest reliability was calculated by 10 (37%) studies. More than one type of validity was discussed in most articles. Content, criterion, convergent, construct, discriminate, concurrent, and face validity were reported by three, five, two, seven, one, five, and three studies, respectively. Hypothesis testing was performed in nine studies, and factor structure was evaluated in four papers. Of the 27 identified scales, eight instruments, including the pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire (PRAQ), pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire-revised (PRAQ-R), pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire short (PRAQ-S), pregnancy anxiety scale (PAS), pregnancy-specific anxiety scale (PSAS), and pregnancy-specific anxiety scale-revised (PSAS-R), specifically focused on pregnancy-related anxiety. Since two scales shared the name of the PAS and two shared the name of the PSAS, scale names were prefixed with author names for clarity. Moreover, two general anxiety scales, that is, STAI and Penn State Worry questionnaire, were included in this review.

The selected studies evaluated a wide range of instruments including tools specifically designed to measure pregnancy-related worries and stress. These tools included pregnancy worries and stress questionnaire (PWSQ), pregnancy-related thoughts, prenatal social environment inventory, baby schema questionnaire, Tilburg pregnancy distress scale, rural pregnancy experience scale, A-Z stress scale, CWS, Cambridge worry scale-revised (CWS-R), high risk pregnancy stress, Oxford worries about labor scale, pregnancy outcome questionnaire, pregnancy experience scale (PES), pregnancy experience scale-revised (PES-R), pregnancy experience questionnaire, prenatal psychosocial profile stress, and prenatal distress questionnaire. Some of the mentioned tools, including the PRAQ-R, PRAQ-S, CWS-R, PSAS-R, and PES-R, were the subscales of a longer instrument.

| Author, Year (Source) | Name of the Instrument | Response Format | Items (Question) | Reliability | Validity | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test-Retest | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||||||

| Navidpour et al., 2015 (2) | Pregnancy worries and stress questionnaire | Five-point Likert scale; from 1 to 5 | 25 | 0.89 | 0.89 | Content validity | Measures pregnancy-related stressors |

| Face validity | |||||||

| Criterion validity | |||||||

| Construct validity | |||||||

| Van den Bergh, 1990 (17) | Pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire | Seven-point scale | 55 | 0.56 | 0.95 | Factor structure | Measures pregnancy fears and worries |

| Construct validity | |||||||

| Huizink et al., 2002 (18) | Pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire-revised | Four-point scale | 34 | 0.76 | 0.82 | Criterion validity | Revised version of the pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire |

| Huizink et al., 2004 (13) | Pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire-short | Five-point scale | 10 | 0.82 | Criterion validity | Short version of the pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire | |

| Construct validity | |||||||

| Cote-Arsenault, 1995 (19) | Pregnancy anxiety scale | Visual analogue scale | 5 | 0.70 | Face validity | Measures pregnancy anxiety | |

| Discriminate validity | |||||||

| Rini et al., 1999 (20) | Pregnancy-related thoughts | Four-point scale | 10 | 0.78 | Factor structure | Investigates women’s pregnancy-related worries and concerns | |

| Orr et al., 1992 (21) | Prenatal social environment inventory | Dichotomous | 41 | 0.73 | 0.90 | Concurrent validity | Measures prenatal stress under chronic stressful conditions |

| Levin, 1991 (22) | Pregnancy anxiety scale | Dichotomous | 10 | 0.80 | Factor structure | A multidimensional tool to assess pregnancy-related anxiety | |

| Gloger-Tippelt, 1983 (23) | Baby schema questionnaire | Six-point scale | 64 | 0.89 | Face validity | Assesses pregnant women’s cognitive representations of their babies | |

| Roesch et al., 2004 (24) | Pregnancy-specific anxiety scale | Five-point scale | 4 | 0.67 - 0.72 | Hypothesis testing | Measures pregnancy-related anxiety | |

| Concurrent validity | |||||||

| Meyer et al., 1990 (25); O’Connor et al., 2013 (26) | Penn state worry questionnaire | Five-point scale | 16 | 0.97 | Concurrent validity | A general tool to measure the trait of prenatal worry | |

| Pop et al., 2011 (27) | Tilburg pregnancy distress scale | Four-point scale | 16 | 0.78 | Concurrent validity | Measures pregnancy distress | |

| Construct validity | |||||||

| Kornelsen et al., 2011 (28) | Rural pregnancy experience scale | Five-point scale | 5 | 0.91 | Content validity | Measures the psychological worries which may cause stress and anxiety in rural women | |

| Construct validity | |||||||

| Spielberger, 1983 (29) | State-trait anxiety inventory | Four-point scale | 40 | 0.90 | Concurrent validity | Objectively measures both state and trait anxiety | |

| Kazi et al., 2009 (30) | A-Z stress scale | 10-point scale | 30 | 0.86 | 0.82 | Hypothesis testing | Measures a wide range of worries and tension about financial roblems, martial relationships, pregnancy-related cultural issues, etc. |

| Green et al., 2003 (31) | Cambridge worry scale | Six-point scale | 16 - 17 | 0.69 - 0.72 | 0.76 - 0.81 | Hypothesis testing | Measures pregnant women’s worries |

| Factor structure | |||||||

| Carmona Monge et al., 2012 (32) | Cambridge worry scale-revised | Six-point scale | 13 | 0.83 | Hypothesis testing | Revised version of the Cambridge worry scale | |

| Goulet et al., 1996 (33) | High risk pregnancy stress | Linear analogue scale; from 0 to 100 | 16 | 0.75 - 0.88 | Content validity | Measures the level of stress in women with high-risk pregnancy | |

| Redshaw et al., 2009 (34) | Oxford worries about labor scale | Six-point scale | 10 | 0.75 | Exploratory factor analysis | Measures worries about labor and birth | |

| Wadhwa et al., 1993 (35) | Pregnancy-specific anxiety scale | True/false | 5 | 0.71 - 0.96 | Hypothesis testing | Evaluates women’s concerns about pregnancy and birth | |

| Rini et al., 1999 (20) | Pregnancy-specific anxiety scale-revised | Four-point scale | 10 | 0.83 | 0.70 - 0.85 | Construct validity | Revised version of the pregnancy-specific anxiety scale |

| Hypothesis testing | |||||||

| Theut et al., 1988 (36) | Pregnancy outcome questionnaire | Four-point scale | 15 | 0.80 | Hypothesis testing | Evaluates concerns about the pregnancy outcome | |

| DiPietro et al., 2002 (37) | Pregnancy experience scale | Four-point scale | 20 | 0.91 | Generalized estimating equations analyses | Assesses the everyday issues and positive and negative feelings experienced by pregnant women | |

| DiPietro et al., 2008 (38) | Pregnancy experience scale revised | Four-point scale | 10 | 0.83 | Criterion validity | Revised version of the pregnancy experience scale | |

| Convergent validity | |||||||

| Hypothesis testing | |||||||

| Da Costa et al., 1998 (39) | Pregnancy experience questionnaire | Three-point scale | 42 | 0.81 - 0.87 | 0.87 - 0.91 | Hypothesis testing | Assesses the psychological distress, attitudes, and adaptability of pregnant women |

| Curry et al., 1998 (40) | Prenatal psychosocial profile stress | Four-point scale | 11 | 0.57 - 0.82 | 0.67 - 0.92 | Construct validity | Measures psychosocial tension during pregnancy |

| Yali and Lobel, 1999 (41) | Prenatal distress questionnaire | Four-point scale | 12 | 0.75 | 0.80 - 0.81 | Convergent validity | Evaluates worries and anxiety about pregnancy and birth |

| Criterion validity | |||||||

4. Discussion

This systematic review focused on instruments evaluating pregnancy-related worries and stress in the domains of health promotion and maintenance. While none of the evaluated instruments were completely suitable for the assessment of worries and stress in healthy pregnant women, the PWSQ, PRAQ, and PRAQ-R showed moderate to strong evidence in most of the examined measurement properties. However, when selecting a particular scale to measure pregnancy worries, the clinicians, nurses, and researchers need to consider not only the characteristics of the target population and settings, but also several factors related to the scale (e.g., the number of items and the specific contents or dimensions of the scale). Pregnancy-related stress consists of fears and worries specifically experienced by pregnant women (13, 42). For instance, the PRAQ (17) does not have adequate items to identify the general symptoms commonly experienced by pregnant women. Meanwhile, the scopes of Levin’s PAS, PRAQ-R, and PRAQ-S are not wide enough, and they are not suitable for evaluating the aspect of anxiety.

Psychometric evaluations, including validity and reliability testing, are also essential when selecting a scale (43). Among the 27 studied scales, the PWSQ (2) enjoyed good validity and reliability, and its items were not ambiguous for the respondents. Nevertheless, its psychometric properties should be further investigated. This scale can be validated and widely used. This assessment is based on correlations with the STAI in a sample of 100 pregnant women. However, this scale does not have a special cut off score, that is, this scale identifies stressors. Despite its good reliability, Levin's PAS was not widely administered, probably due to the limitations caused by its dichotomous responses. No data about the validation of this scale was provided in the selected studies. The PRAQ, developed by Van den Berg, had the greatest factor loading. The scale was later shortened due to low factor loading, and some items were excluded due to high error variance. The PRAQ-R and PRAQ-S could not be independently used as they had limited scopes and failed to consider the physiological aspect of anxiety. In fact, none of the studied pregnancy-specific scales considered the physiological aspect of anxiety. The pregnancy-related thoughts covered a wide range of fears and worries but included only a single indicator for each. Shorter scales assess pregnancy-related worries through one item. Despite their advantages, the limited number of items in shorter scales usually results in poorer psychometric properties (43). On the other hand, as indicated by some researchers, a large number of items might prevent the respondents from providing accurate responses (44). Although some of the studied scales could predict pregnancy outcomes, they sometimes lack a scientific background (15).

Moreover, some scales did not yield different results when measuring pregnancy-related worries and anxiety in general. Therefore, pregnancy-related scales developed based on the relevant scientific principles can be more reliably used for the identification of pregnancy-specific worries. This will, in turn, facilitate the design of effective interventions to decrease the stress and worries experienced by pregnant women. Furthermore, successful health assessment in pregnant women will depend on the integrated use of well-designed tools. Considering the negative effects of pregnancy-related worries and stress on maternal and fetal health, developing a valid, reliable, and usable scale for the identification of sources of stress in pregnant women seems critical. Relevant interventions can then be designed based on the information obtained from the administration of such a scale.

Finally, some items of particular scales can be confounding for pregnant women. Moreover, incompatible results might be obtained if a scale contains highly somatic contents or ambiguous items such as nausea, vomiting, and breathlessness, common symptoms experienced by many pregnant women (45).

4.1. Limitations

Like any other study, this systematic review has some limitations. Some studies had low methodological quality as their sample size was too limited for the number of items included in the scale. In addition, the evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies and the quality of the results might have been affected by the information on measurement properties presented in the reviewed articles.

4.2. Conclusion

Pregnancy-related stress is a definite anxiety response in pregnant women. Since stress and worries can cause negative pregnancy outcomes including preterm labor and low birth weight infants, a well-developed scale with acceptable performance and psychometric properties is required to measure pregnancy-related worries. General tools previously adopted to assess worries and stress in pregnancy need further psychometric testing to confirm their reliability and suitability for the prenatal period. A well-developed instrument is of high clinical significance as it can facilitate the design of relevant interventions to decrease stress and anxiety in pregnant women. Further research toward the development of such scales is warranted.