1. Background

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can broadly be described as a process aimed at correcting physiological disorders in critically ill patients or resuscitating them from states such as anesthesia or apparent death. Therefore, the term "resuscitation" is used in this study to describe CPR, trauma, and the critical care of critically ill patients. In the United States, more than 200,000 adults are hospitalized, and in Germany, more than 2,000 people in emergency rooms undergo CPR each year (1).

Participating in a resuscitation event requires both emotional and physical preparation, during which the competence of all involved is seriously and publicly tested. When performed successfully, the outcome is invaluable. Research indicates that both internal and external stressors are associated with the process of resuscitation (2).

The healthcare system has shifted from a paternalistic approach toward a principle of personal autonomy, and family members now often expect to be actively involved in care decisions related to the treatment of their relatives. Even during resuscitation, patients prefer to have their relatives nearby, and many family members wish to be present if possible. For this reason, family presence during resuscitation is becoming a developing healthcare practice, even though most of the existing evidence is of low quality and does not thoroughly examine the perceptions and psychological consequences for relatives or their impact on patient morbidity and mortality (3). In some cases, nurses who are family members of the patient are active participants in CPR, from the diagnosis of cardiorespiratory arrest to the conclusion of resuscitation efforts (4).

A nurse can be present both at the time of diagnosis and during discussions about treatment options with the patient. Consequently, nurses can enhance patients' understanding of their diagnosis and available treatment options, while also offering psychological support throughout the course of the illness. The nurse’s role in supporting the patient’s family mirrors their role with the patient, extending even beyond the patient’s death to provide assistance during the grieving process. Fulfilling this role requires the nurse’s ability to communicate sensitively, maintain openness, and engage emotionally (5).

The impact of a life-threatening disease on both the patient and their family members is well documented (6-9). Such a disease affects patients directly and also requires family members to take on the role of informal caregivers (6). Nurses who are family members of the patient are also part of this caregiving group.

The tasks and burdens associated with caregiving are often varied and numerous, and they frequently change over the course of the disease (9). These tasks may range from offering emotional support to handling practical responsibilities, such as feeding, bathing, assisting with daily activities, and managing destructive behaviors. Families may need to make significant lifestyle adjustments to meet caregiving responsibilities and cope with related stressors — all while continuing to fulfill essential roles within their family and social lives, such as those of spouse, parent, friend, or employee. These caregiving responsibilities are typically undertaken by close relatives who often live in the same household, motivated by love and the desire to avoid institutionalizing their loved one. However, the burden of caregiving can lead to relational difficulties, changes in the caregiver’s personality, and limitations on personal life, work, and leisure activities. Providing unpaid and unsupported care can negatively affect caregivers’ physical health, mental well-being, and financial stability (10).

Typically, caregivers are involved in scenarios where they must navigate and address patients’ thought processes, emotional states, and personal beliefs. When a serious illness affects the family of a professional nurse, particularly a close relative, the nurse often assumes the responsibility of caring for their loved one. In such cases, the nurse’s emotional involvement is deeper, the emotional impact more severe, and the sense of responsibility greater. Studies have shown that emotional distress is a common issue in these situations (11).

Research on the psychosocial effects of caring for a person with a life-threatening disease has shown that both informal caregivers and healthcare professionals experience intense emotions, such as helplessness, fear, and anxiety (12, 13). However, few studies have explored the experiences of nurses who find themselves in the dual role of being both an informal caregiver and a healthcare professional for their family members (14).

While the responsibilities and emotions of informal caregivers have been extensively studied, no current research specifically addresses the unique and challenging scenario in which a nurse provides care to a family member with a life-threatening illness (15).

While the responsibilities and emotions of informal caregivers have been widely studied, there is currently no research that addresses the challenging scenario in which a nurse provides care to a family member facing a life-threatening illness (15). Given that part of nurses’ caregiving in CPR involves their own family members — and that nurses, at the same time, strive to fulfill their professional duties as formal healthcare providers for their relatives — their dual roles as both formal and informal caregivers present significant challenges. Exploring these challenges and perceptions can contribute meaningfully to the psychological rehabilitation of nurses.

2. Objectives

Consequently, this study was conducted to explore the lived experiences of Iranian Muslim nurses performing CPR for their family members.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Participant

Using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, we analyzed and interpreted the descriptions of nurses’ lived experiences of performing CPR on their family members. The meanings of these experiences were structured according to Van Manen’s (16) descriptions of the four life worlds: Rationality, corporeality, spatiality, and temporality. This research was conducted in Dezful, Iran, from June to August 2023. Participants were selected through purposive sampling. The inclusion criteria were: Having at least a bachelor’s degree in nursing, having had CPR experience involving a family member, and willingness to participate in the study. The study’s purpose and participant eligibility criteria were electronically shared in online nursing groups. Interested participants contacted the researcher via virtual networks and expressed their willingness to be interviewed. In some cases, participants were referred by emergency department nurses who regularly encountered resuscitation scenarios and were familiar with colleagues who met the inclusion criteria. To achieve data saturation, nurses from different regions of the country — representing diverse cultures, education levels, and genders — were included in the study.

Interviews were conducted in comfortable and appropriate settings, such as a meeting space at the researcher’s workplace or office. For non-local participants, telephone interviews were conducted. Each interview began with the following open-ended questions: “Please tell me how you felt when your patient needed CPR?”, “What did you do?”, “Could you control your emotions?”, and “Who supported you?” Follow-up analytical questions were then posed based on the participants’ responses. The interviews lasted between 32 and 55 minutes and were systematically recorded using audio tapes. Each participant was assigned a unique code number for identification purposes. The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim for data analysis. New participants continued to be recruited until data saturation was reached — that is, when no new or unique insights emerged beyond those already provided by earlier participants (17).

To protect participants emotionally, the interviewer first prepared both himself and the participant and explained the purpose of the study. The participant's trust and confidence were established through the interviewer’s personal introduction. During the interview, the interviewer employed skills such as active listening and providing constructive feedback. Given that both the interviewer and the participants were experienced professionals, the interviewer also demonstrated empathy and effectively managed emotional dynamics throughout the interaction. Participants were assured that, if psychological counseling was required, they would be referred to a counselor at the researcher's expense.

Van Manen’s approach was used to analyze and interpret the data (18). Manual data analysis was conducted by the researchers using the highlighting technique. Words, phrases, and statements that described nurses’ lived experiences of performing CPR on their family members were identified. These statements were then isolated and subjected to phenomenological analysis. The trustworthiness of this study was assessed using Lincoln and Guba's criteria (1985), which include credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. MAXQDA software, version 2018, was used for coding and categorizing the data. Credibility was established through prolonged engagement, as the researcher had been actively involved in emergency patient research for eight years. Additionally, her previous experience as a nurse and instructor in the emergency room enabled her to build strong relationships with the study participants, further enhancing the research’s credibility. The researcher and participants had prior professional relationships as colleagues, which helped foster trust and created a supportive environment for conducting in-depth interviews. Member checking was also performed: Selected portions of the transcribed text, along with corresponding codes and categories, were shared with supervisors to gather their feedback and ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data analysis process. To ensure the appropriateness of the findings, the research results were also shared with nurses who were not participants in the study, and their confirmation of the findings was sought. Additionally, a diverse sampling strategy was employed to enhance the applicability of the results across various contexts. Finally, detailed documentation and transparent reporting of the research processes were carried out to ensure the study’s validity, thereby allowing for future scrutiny and replication.

In terms of reflexivity, it is important to note that the researcher was personally connected to the subject matter of the study. Although efforts were made to minimize the influence of personal biases during data collection and analysis, the researcher acknowledges that achieving complete objectivity is inherently challenging. To enhance the credibility of the findings, the data analysis was reviewed and validated by a fellow researcher with extensive experience in qualitative research. This collaborative approach aimed to reduce potential biases and ensure a more nuanced interpretation of the data. This research was derived from a proposal entitled "Iranian Nurses' Experiences of Caring for Their Family Members During CPR: A Phenomenological Study", approved by the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Dezful University of Medical Sciences (IR.DUMS.REC.1402.037). The authors express their sincere gratitude to all the participating nurses for their cooperation. Ethical considerations were strictly observed, including preserving anonymity, obtaining written informed consent, maintaining data confidentiality, and ensuring participants' right to withdraw from the study at any time.

4. Results

Nine nurses were eligible to participate in the study, with a mean age of 37 years, ranging from 25 to 44 years. Three participants were men and six were women. Two participants held a baccalaureate degree, six had a master’s degree in nursing, and one held a Ph.D. The mean duration of employment was 14.3 years, with a range of 3 to 20 years. All participants had experience with more than one case involving the care of a family member during CPR (Table 1).

| No. | Age | Gender | Level of Education | Work Experience | Relatives | CPR Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | Female | PhD | 14 | Father | Chronic |

| 2 | 21 | Female | MSD | 20 | Father-in-law | Acute |

| 3 | 32 | Female | MSD | 12 | Grandmother | Acute |

| 4 | 32 | Female | MSD | 12 | Aunt | Chronic |

| 5 | 44 | Male | MSD | 20 | Mother | Chronic |

| 6 | 44 | Male | MSD | 20 | Father | Acute |

| 7 | 44 | Male | MSD | 20 | Father-in-law | Acute |

| 8 | 32 | Female | BS | 8 | Cousin | Acute |

| 9 | 25 | Female | BS | 3 | Mother | Acute |

Demographic Characteristics and Background Information of the Participants

4.1. Review of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Conditions

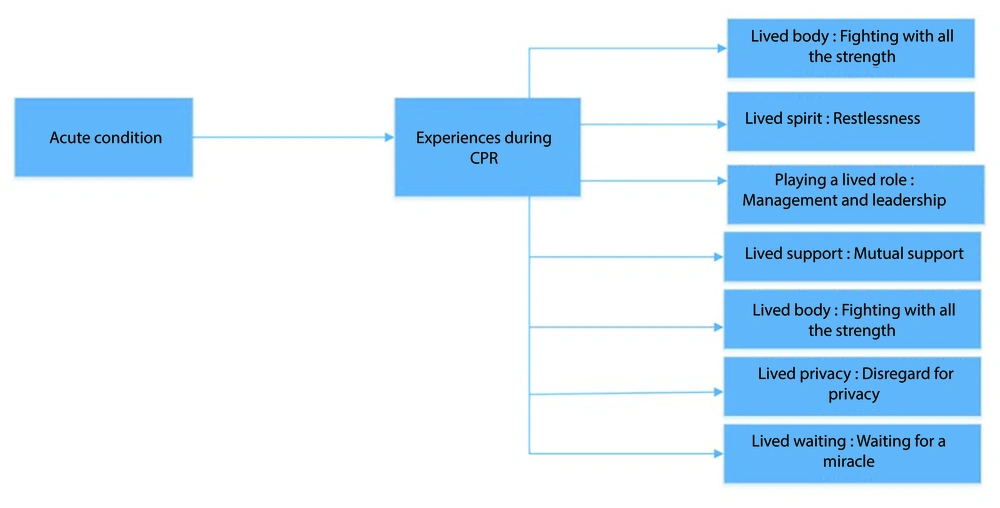

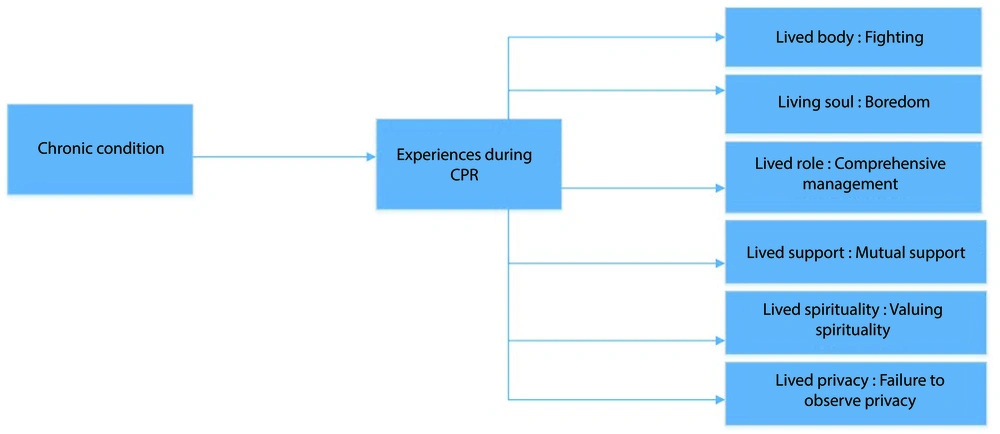

To understand the experiences of nurses with regard to CPR performed on their family members, it is necessary to describe the contextual background. The participants stated that CPR is a critical and life-threatening condition, and in such situations, nurses are expected not only to care for the patient but also to provide therapeutic intervention — making it an extremely dangerous and stressful experience. The conditions under which a patient requires CPR can be categorized as either acute or chronic. In acute conditions, CPR is often required due to unexpected events such as accidents, heart attacks, or strokes, with no prior medical history. In contrast, chronic conditions leading to CPR include cardiorespiratory failure, cancer, or the terminal stages of various diseases. In acute scenarios, CPR is typically a sudden and shocking event for the nurse, who may not be mentally or emotionally prepared. However, in chronic conditions, the progression toward death is often anticipated, and in many cases, the death is considered "planned" or expected, making it somewhat easier for the nurse to come to terms with the situation. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the lived experiences of Iranian Muslim nurses in acute and chronic conditions leading to CPR, respectively.

4.2. Acute Conditions

In the analysis of nurses’ lived experiences of performing CPR on their family members under acute conditions, seven subcategories were identified. These include: Fighting with all their strength, restlessness, management and leadership, mutual support, forgotten spirituality, disregard for privacy, and waiting for a miracle (Figure 1).

4.2.1. Lived Body: Fighting with All Its Strength

Most of the participants reported experiencing physical symptoms such as sweating, tachycardia, and trembling limbs when confronted with their critically ill family members. They described feelings of extreme emotional distress, likening the experience to having their heart ripped from their chest. Those with a history of conditions such as dizziness or chest pain noted a recurrence or intensification of their symptoms during the event. The physical and psychological effects persisted long after the incident; some participants reported experiencing nightmares and sleep hallucinations. Additionally, one participant shared a traumatic outcome involving pregnancy loss following a CPR episode.

Patient 9: "When I saw that my mother had an arrest, I felt so anxious that my heart was about to burst".

Patient 8: "When my cousin had an arrest, I completely forgot that I was two months pregnant, jumped on the ICU bed, and started the cardiac massage. After 4 - 5 days, I had vaginal bleeding, and the doctor said that the baby had been miscarried".

4.2.2. Lived Spirit: Restlessness

All participants reported being shocked upon hearing the bad news. They described being overtaken by restlessness and experiencing symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They noted that encountering a similar situation in which a patient requires CPR often re-triggers the same intense stress and emotional turmoil. Emotional responses such as crying were also commonly reported. Many participants shared that they had long harbored chronic anxiety about the possibility of performing CPR on a family member. After the event occurred, the memory of the scene frequently replayed in their minds, accompanied by a persistent fear of it happening again. Most participants expressed satisfaction with their performance during the CPR episode. However, one participant, who was pregnant at the time, reported feeling inadequate due to her inability to participate in the resuscitation effort. This experience, coupled with the traumatic context, contributed to severe postpartum depression.

Patient 6: "Until one year after my father's death, I was thinking about his CPR and reviewing it myself. I was in control of my mind and crying".

Patient 2: "What bothered me after the death of my father-in-law was the feeling of inadequacy because I was pregnant when he had an arrest, and I knew that if I did CPR, my child would be miscarried".

4.2.3. Playing a Lived Role: Management and Leadership

Most participants stated that they managed the CPR process themselves and did their best to make appropriate clinical decisions. Some noted that, at the time, they deliberately withheld the distressing news from other family members to protect them from immediate emotional shock. In one case, a participant who was pregnant at the time chose not to physically engage in CPR in order to safeguard her own health and that of her unborn child. Instead, she supervised the resuscitation process and instructed others on how to perform cardiac massage.

Patient 3: "Although it was a very difficult task, I concentrated on performing CPR on my patient according to the protocol".

4.2.4. Lived Support: Mutual Support

In most cases, the nurse provided emotional and psychological support to the family, offering comfort to those in distress. At the same time, the nurse also received emotional support from family members and colleagues.

Patient 9: "All my colleagues gathered around me, consoled me, and said that God willing, CPR will be successful".

Patient 2: "When my father-in-law was taken to the hospital, my mother-in-law comforted me and said that he was too old, and for the sake of your own and your child's health, be calm and leave the house so you don't have to see others mourning".

4.2.5. Lived Spirituality: Forgotten Spirituality

While most participants did not prioritize spiritual care in such situations, those who had received strong encouragement from the patient to address spiritual needs during end-of-life stages provided spiritual care implicitly.

Patient 8: "My cousin's condition was so acute that spiritual care had no place. I concentrated all my energy on his physical care to keep him alive because he was young".

Patient 7: "My father had already told me to read the Quran and do nothing else if he died".

4.2.6. Lived Privacy: Disregard for Privacy

All participants reported that nurses made efforts to ensure privacy for female patients during CPR but often overlooked it for male patients.

Patient 8: "When the patient is a man, there is no need for privacy anymore, unless we want to open the curtains around the bed so that the other patients do not see the CPR".

Patient 4: "In the case of my grandmother, I drew the curtains around the bed during CPR so that other patients would see nothing and would not be scared".

4.2.7. Lived Waiting: Waiting for a Miracle

Most participants stated that their families expected them to continue CPR efforts and revive the patient, regardless of the prognosis. Only in one case — where the patient had explicitly requested that no CPR be performed — did the family expect the nurse to respect that wish and refrain from attempting resuscitation.

Patient 8: "My uncle, who was the father of the patient, looked at me as if he was just waiting for the good news of his son, while his son had a severe brain injury and it was impossible to survive".

Patient 3: "My family was behind the door of the ICU and just told me to keep trying".

4.3. Chronic Conditions

In the analysis of nurses’ lived experiences of performing CPR on their family members under chronic conditions, six subcategories were identified. These include: Fighting, boredom, comprehensive management, mutual support, valuing spirituality, and failure to observe privacy (Figure 2).

4.3.1. Lived Body: Fighting

Most participants experienced restlessness, heart palpitations, sweating, and tremors in response to the patient's critical condition. These physical symptoms often persisted for a long time and contributed to ongoing sleep disturbances.

Patient 1: "The CPR always comes before my eyes because my father had an arrest in the middle of the night, and it made me unable to sleep".

Patient 5: "When they told me that my mother was ill and that they were taking an ambulance to the hospital, I was restless and walking in the yard in front of the emergency door".

4.3.2. Living Soul: Boredom

Most participants stated that they were mentally and emotionally prepared to understand the situation prior to the CPR. Some mentioned that after the patient's death, their stress diminished and transformed into the sorrow of loss. They reported surrendering to the reality of the situation, consistently engaging in critical thinking about CPR, and expressed satisfaction with their performance in all cases. Despite accepting the patient’s death, they frequently described feelings of boredom and homesickness stemming from the loss of a loved one.

Patient 5: "After my mother's death, I didn't feel happy about anything for a year, as if happiness had no meaning for me".

Patient 5: "When the end of my mother's CPR was announced, all the stress I had because of her bad condition subsided and was replaced by sadness because of her loss".

4.3.3. Lived Role: Comprehensive Management

Most participants stated that they avoided providing futile care and focused on effectively managing and performing CPR. In addition to resuscitation, they also administered palliative care to ensure the patient's comfort and dignity. Maintaining professional integrity and practicing self-management were highlighted as important aspects of their role. Many participants also reported staying with the patient after death and continuing care until the burial.

Patient 1: "During my father's CPR, although I followed the latest CPR guidelines, I did not do any useless things. For example, I announced the end of CPR, which lasted half an hour".

Patient 5: "I was by my mother's side from the beginning of CPR until wrapping her in the cover and going to the funeral home and burying her".

4.3.4. Lived Support: Mutual Support

Most participants stated that they sought help, gathered family members around the dying patient, and encouraged them to accept the reality of the patient’s death. They took responsibility for supporting both the deceased and their family members, and they continued to offer consolation after the patient’s passing. Some participants also noted that they received emotional support from family members during this time.

Patient 1: "After my father's death, all the family members thanked me for the help I gave to my father, and I also thanked my mother for the efforts she made for my father".

Patient 5: "After my mother's death, we all consoled each other".

4.3.5. Lived Spirituality: Valuing Spirituality

Some participants stated that they sought spiritual solace by asking their patient for halal (forgiveness or permission), reciting the Quran, praying, and acting in accordance with the patient’s final wishes. These actions were intended to calm the patient's mind and honor their spiritual needs during the end-of-life stage.

Patient 1: "When I was doing CPR on my father, I was always sending blessings".

4.3.6. Lived Privacy: Failure to Observe Privacy

Most participants stated that they were attentive to maintaining privacy when the patient was female. However, privacy was less commonly observed in cases involving male patients.

Patient 1: "In the case of my father, since there were no other patients in the CPR room, we did not observe his privacy".

5. Discussion

This study explored the lived experiences of Iranian Muslim nurses who performed CPR on their family members. Ultimately, two major themes — acute and chronic conditions — and seven subthemes were identified: Lived body, lived spirit, playing a lived role, lived support, lived spirituality, lived privacy, and lived expectation.

Under acute physical conditions, participants reported experiences such as sweating, tachycardia, body tremors, dizziness, chest pain, nightmares, sleep disorders, hallucinations, and even miscarriage. These findings are consistent with those of Hansen, who also documented the occurrence of physical symptoms, mental distraction, and fatigue among nurses following the care of family members (19). Similarly, a study by Mills and Aube Luck revealed that caregiving responsibilities negatively affected caregivers’ quality of life, particularly their physical health (14).

In the present study, under acute psychological conditions, nurses reported experiencing shock and emotional distress upon receiving news about their family member’s critical state. Common responses included restlessness, symptoms of PTSD, crying, persistent critical thinking about CPR, rumination over the event, and fear of its recurrence. Despite the emotional toll, many nurses expressed satisfaction with their performance during CPR. However, in situations where they were unable to participate — such as during pregnancy — feelings of incompetence and depression were reported. These findings are consistent with a study by Bailey, in which some caregivers expressed positive feelings about their ability to provide care and comfort to loved ones. They reported a sense of satisfaction and an increase in empathy within their professional roles (20). In contrast, under chronic conditions, nurses often exhibited greater mental and spiritual preparedness, enabling them to accept the situation more calmly. Many participants described a reduction in stress following the patient’s death, followed by a period of mourning and emotional adjustment. Other common experiences included surrendering to reality, accepting the inevitability of death, engaging in critical reflection about CPR, and being content with their own performance. Supporting these findings, Salmond’s study revealed that family members of nurses who dealt with critical illnesses experienced acute panic, fear, and anxiety. They often engaged in "what if" ruminations regarding their caregiving, which contributed to burnout (21). Furthermore, the nurse’s compassion for their terminally ill family member was shown to provoke anxiety, depression, and despair. From the nurse’s perspective, the death of a loved one was sometimes perceived as a personal failure, highlighting the psychological burden associated with their dual role. Additionally, the responsibility of managing the emotional responses of other anxious family members further complicated the caregiving process (22).

In the present study, nurses who performed CPR often assumed leadership roles within the resuscitation team, taking responsibility for guiding clinical actions and striving to make accurate and timely decisions. Under chronic conditions, nurses consciously avoided futile interventions and focused on managing care effectively. They also engaged in palliative care, while striving to uphold professional integrity and practice self-management. Most nurses remained with the patient after death and continued caregiving until the burial, reflecting a profound sense of moral and spiritual duty (23).

The majority of Iranians are Muslims who believe in the resurrection of the body. In Islam, death is recognized as an inevitable aspect of human existence. Consequently, preserving and protecting life is regarded as both a virtue and a religious obligation. Preventing premature death is considered a moral duty, and Muslim healthcare providers are expected to offer care that alleviates suffering. In acute emergencies, such as during CPR, immediate physical care is prioritized. However, in chronic conditions, more time and attention can be allocated to providing palliative care (24). It is also important to note that palliative care at the end of life is acknowledged and accepted by all major religions (25). Despite this, studies have shown that Muslims often do not receive the level of palliative care that would be expected based on religious and ethical considerations (26).

In this study, under acute conditions, nurses provided emotional and psychological support to their family members and comforted those in distress. Simultaneously, the nurses themselves received mental and emotional support from both family and colleagues. Previous studies have shown that relatives often receive increased attention during supervision and initial medical interventions, reflecting a form of peer support from fellow healthcare professionals. Members of the nurse’s family were frequently involved in clinical decision-making as part of the care team, which contributed to greater satisfaction with the care provided to the patient (21). Although family members of nurses often experience significant concern, they may refrain from openly expressing their emotions — highlighting the nurse’s role in maintaining emotional control and stability within the family (27). Research also underscores that nurses view providing support to patients as a professional responsibility, grounded in their specialized knowledge. This sense of duty enhances their ability to deliver effective care. Moreover, nurses often serve as advocates for their patients, voicing concerns and questioning the quality of care when they perceive that standard protocols are not being followed (20, 28).

In the present study, under chronic conditions, nurses sought help, gathered family members around the dying patient, encouraged them to accept the impending death, and provided support to both the patient and the family. After the patient’s death, they continued offering emotional consolation. Some participants also reported receiving emotional support from family members. In contrast, a study by Kongsuwan found that nurses often lacked the time to provide psychological support to their own families due to the demands of their professional role (29).

Regarding spiritual care, this study found that it was rarely provided during acute situations, except when patients had previously requested it — highlighting the difficulty of implementing spiritual support in critical, time-sensitive scenarios (30). However, under chronic conditions, nurses made efforts to calm the patient by reciting the name of God. This contrasts with Kongsuwan’s findings, which indicated that nurses often lacked the necessary competence and skills to deliver spiritual care effectively (29).

In the present study, privacy was respected for female patients in both acute and chronic conditions, but not consistently for male patients. In this regard, a study by Bigdeli Shamloo et al. highlighted the challenges and possibilities of maintaining the privacy of trauma patients. One contributing factor to the lack of privacy, particularly for male patients, was the overcrowding of critically ill and trauma patients in the CPR room, which often hindered the proper observance of this aspect of care (24).

This study also found that families generally expected nurses not to terminate CPR and to continue efforts to revive the patient. Only in cases where the patient had previously requested that CPR not be performed did families support the nurse in withholding resuscitation. The decision to end CPR was described as extremely difficult and emotionally complex (31). Moreover, beyond resuscitation efforts, nurses were expected to care for both the patient and their family members simultaneously, placing significant emotional and professional demands on them (28).

Among the limitations of this study, it should be noted that the focus was solely on Iranian nurses. Generalizing the findings to nurses from other cultural backgrounds requires cross-cultural research. Additionally, the small sample size (9 participants) and the qualitative nature of the study limit the broader applicability of the results.

5.1. Conclusions

The experience of performing CPR on family members imposes a significant emotional and professional burden on nurses, highlighting the need for comprehensive support from the healthcare system, families, and society. Integrating cultural and religious considerations into the design of this support is essential for enhancing nurses' resilience and overall well-being.