1. Background

To be human is to be perfectly imperfect. However, civility demands a flawless performance, requiring us to suppress darker emotions and present a socially acceptable facade. Consequently, parts of the self engage in criticizing other parts, set unattainable ideals, and even experience shame due to unacceptable aspects, ultimately leading to a lack of self-acceptance.

This study considers a lack of self-acceptance as the rejection of certain emotions, behaviors, or beliefs about oneself, accompanied by resistance to these aspects emerging. This resistance results in the avoidance of specific emotional, cognitive, and behavioral experiences.

For nearly a century, various conceptualizations have emerged around the lack of self-acceptance, underscoring the complexity of this phenomenon. For instance, Rogers introduced the term “Conditional Positive Regard” to conceptualize a lack of self-acceptance (1, 2), asserting that it is linked to family interaction patterns. In contrast, Ellis argued that individuals’ irrationality toward themselves, known as global self-evaluation, fosters a lack of self-acceptance (3). Levin and Hayes (4, 5) attributed this phenomenon to psychological inflexibility, suggesting that the avoidance of private experiences contributes to a lack of self-acceptance.

These conceptualizations highlight the diversity of perspectives on the origins of a lack of self-acceptance. While established theories provide foundational insights, ongoing research continues to explore the complexities of this phenomenon. This qualitative study delves into the lived experiences of psychologists facing self-acceptance issues, aiming to uncover deeper insights into the internal struggles and personal narratives that shape this condition.

Moreover, there has been a long-standing lack of consensus regarding how a lack of self-concept is formed and the relative influence of intra- and interpersonal variables. A prominent notion in self-view theory and research is that behavior, cognition, and emotions related to the view of the self are guided by internal working models (IWMs), as conceptualized by Bowlby (6). When early relationships provide a child with secure attachment, the child develops healthy working models, fostering a positive self-attitude due to a stable and reliable external social environment (7). Conversely, an insecure attachment style reflects IWMs associated with beliefs such as “I am unlovable,” “I am not worthy,” and “I am defective”.

Other studies move beyond the exclusive examination of maternal parenting behavior, emphasizing the role of dyadic and triadic family interaction patterns (involving mother, father, and child) (8) as well as social configurations involving multiple individuals (9). For example, recall of early life events, such as submissiveness (10), has been shown to influence people’s self-beliefs (11). These coded experiences or "self-schemas", as described in cognitive theories, originate from interactions with others and can alter individuals’ body memory and feelings about themselves (12).

However, Thompson et al. (13), along with Brown et al. (14), propose that not only interpersonal relationships but also intrapersonal growth from within plays a critical role in forming self-concept, further adding to the complexity of the issue. Although these studies have advanced our understanding of the factors influencing the formation of self-concept and, consequently, a lack of self-acceptance, considerable ambiguity remains regarding the specific roots and causes of a lack of self-acceptance.

On the other hand, a lack of self-acceptance is closely related to many trans-diagnostic underlying factors involved in mental disorders. Studies have shown that a lack of self-acceptance contributes to perfectionism (15-17), self-criticism (18, 19), and shame (20, 21). Since perfectionism, self-criticism, and shame are among the most common underlying factors in psychological disorders, it is evident that a lack of self-acceptance plays a critical role in the development of these disorders. As a result, self-acceptance is an integral component of many current therapeutic modalities, such as dialectical behavior therapy (22), rational emotive behavior therapy (23), and acceptance and commitment therapy (24).

Despite the significance of self-acceptance, few studies have directly examined personal narratives, and the specific grounds for a lack of self-acceptance. Most existing research has focused on broader concepts related to self-concept or self-view, or on investigating the effects of increasing self-acceptance. Although extensive research has been conducted on broader constructs such as self-view and self-concept, as well as on the consequences of a lack of self-acceptance—such as shame, perfectionism, and self-criticism—there is a notable absence of studies specifically addressing the reasons and personal narratives that contribute to a lack of self-acceptance in individual cases.

By delving deeply into the origins of a lack of self-acceptance and understanding it more clearly, we can gain a deeper insight into the factors underlying this phenomenon. Such understanding can guide the development of more targeted therapeutic and preventative approaches to address the root causes of these issues. Ultimately, this research could contribute to promoting self-awareness and enhancing overall well-being.

2. Objectives

Given that a lack of self-acceptance manifests in various ways, and considering the insights provided by existing theories, it is likely that multiple factors contribute to individualized experiences of this phenomenon. The current qualitative study aims to explore these experiences by examining the personal narratives and internal struggles of individuals dealing with a lack of self-acceptance.

To achieve these objectives, an interpretive approach employing a qualitative methodology is well-suited to provide the most comprehensive insights in the absence of existing data. Accordingly, this study was designed to include in-depth interviews conducted in a natural context with psychologists whose relevant personal experiences position them as key informants.

3. Methods

Given the complexity and multifaceted nature of a lack of self-acceptance, this study explores the lived experiences of psychologists dealing with self-acceptance issues. Since they have carefully examined their own lives and growth conditions over many years to address their lack of self-acceptance, delving into their narratives can provide deeper insights into the phenomenon. Moreover, psychologists’ professional training may have enabled them to closely observe and analyze the factors contributing to their lack of self-acceptance.

Reflexive thematic analysis was employed to gain a deep and comprehensive understanding of the roots and causes of a lack of self-acceptance. In this method, researchers play an active role in knowledge production (25), and coding is derived from the data itself rather than from pre-existing theories (26). Additionally, a latent thematic analysis approach was utilized to uncover patterns and underlying concepts within the data (27). This approach allowed for the exploration of emerging ideas and the construction of a nuanced understanding of the phenomenon using an inductive approach.

Participants were recruited from a pool of psychologists with expertise in self-acceptance and a demonstrated clinical interest in the topic. Inclusion criteria included: Being a psychologist, acknowledging past struggles with perfectionism, self-criticism, or shame, participating in therapy for their condition, demonstrating clinical interest in self-acceptance, and a willingness to share their personal experiences. Purposive and snowball sampling methods were employed, and conceptual saturation was reached by the 25th interview; however, five additional interviews were conducted to "tell a rich story" (28).

This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Semnan University (approval number IR.SEMUMS.REC.1399.151). Prior to the interviews, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, provided their consent, and selected their preferred interview format (in-person, online, or by phone). Verbal consent was also obtained for digitally recording the interviews to ensure all details were preserved. At the start of each interview, participants’ demographic information was collected to confirm eligibility. Additionally, participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

An open-ended, pre-ordered, semi-structured questionnaire was designed to guide the interviews. Initial questions, such as “What was the story of your acquaintance with this area of self-acceptance in your personal life?” and “Why do you think you could not accept some aspects of yourself before?” focused on general topics. More sensitive questions were introduced once rapport was established, such as: “When and which unacceptable characteristic did you consciously accept for the first time?” and “Could you please tell us about any issues that caused a lack of self-acceptance in your case?” Probing questions, like “What do you mean by that?” and “Could you please explain or clarify further?” were asked as needed. Interview durations ranged from 45 to 90 minutes.

The data analysis process followed the six steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (29): Familiarization, coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing a report. To implement these steps, immediately after completing each interview, the researchers repeatedly listened to the audio recordings and transcribed them using Microsoft Word 2021. The texts were then reexamined to achieve a more comprehensive understanding.

Significant statements from the interviewees were meticulously coded. Using a constant comparison approach, the open codes were grouped under more general and abstract headings based on similarities in content and meaning. Subsequently, the underlying themes of codes within the same category were extracted, named, and reviewed. These themes were then defined in detail, and finally, a comprehensive report of the findings was prepared (Table 1). The interviews were conducted between March 2022 and November 2023.

| Overarching Theme | Themes | Subthemes | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tripartite adversities involved in the formation of a lack of self-acceptance | Intrapersonal adversity | Life-threatening experiences | Experiencing physical danger; being unwanted; injury during birth; experiencing early illness |

| Interpersonal adversity | Experiencing deficits in nurturance | Receiving inadequate parental care; facing emotional coldness; experiencing loss ; experiencing rejection (gender-based rejection or body-shape rejection) | |

| Restricted autonomy | Being underestimated; having activities devalued; being controlled; being overprotected | ||

| Disrupted trust | Having excessive responsibilities; experiencing physical abuse; experiencing being unburdened on; experiencing deception | ||

| Exposure to strict standards | Exposure to strict expectations; experiencing unfavorable comparisons; parental praise of perfectionism; exposure to fear-based discipline; exposure to obligatory change; pressure to achieve; being exposed to rigid sociocultural norms; being exposed to rigid religious beliefs; being exposed to social media’s standards | ||

| Socio-cultural adversity | Minority group status | Being among religious minorities; being among sexual minorities; having a physical disability; being among the economic minorities; being among ethnic minorities |

Trustworthiness was ensured using Lincoln et al.’s criteria (30). The researchers extended the research process to engage deeply with the data and gain a comprehensive understanding of the diverse perspectives and interpretations of the participants. Step-by-step findings were shared with some participants to verify the accuracy and correctness of the researchers’ understanding of their experiences. Additionally, the step-by-step data analysis, extracted codes, and categorization were reviewed and discussed with experts familiar with qualitative methods and the subject of self-acceptance (peer review) to largely ensure credibility.

To ensure consistency, a clear audit trail of the research process was maintained including audio recordings and the immediate transcription of each interview. The data analysis was facilitated using MAXQDA18 software. Furthermore, rigorous auditing, extending the study duration, frequent data reviews, bracketing, and journaling of researchers’ thoughts were employed to minimize bias and maximize neutrality.

Finally, applicability was improved through detailed descriptions of all research steps, participant responses, and the inclusion of direct quotes, enabling other researchers to make informed judgments about the study.

4. Results

The participants (30 psychologists), aged between 30 and 73 years, included 17 males and 13 females. The sample comprised 21 individuals with a Ph.D. in psychology, 1 individual with a Ph.D. in psychoanalysis, 5 individuals with a master’s degree in psychology, 1 individual with a medical doctorate, and 2 Ph.D. candidates in psychology (Table 2).

| No | Gender | Age | Therapeutic Approach & Occupational Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 44 | REBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 2 | Female | 58 | CBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 3 | Male | 38 | Analytical psychotherapist |

| 4 | Male | 41 | ACT psychotherapist & professor |

| 5 | Female | 56 | CBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 6 | Female | 60 | Gestalt therapist |

| 7 | Male | 49 | Person-centered therapist |

| 8 | Female | 48 | ACT psychotherapist |

| 9 | Female | 45 | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapist |

| 10 | Male | 73 | ACT psychotherapist & professor |

| 11 | Female | 43 | Existential psychotherapist |

| 12 | Female | 39 | Gestalt therapist & professor |

| 13 | Male | 52 | CBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 14 | Male | 39 | ACT psychotherapist |

| 15 | Male | 45 | ACT psychotherapist & professor |

| 16 | Male | 40 | CBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 17 | Male | 42 | ACT psychotherapist & professor |

| 18 | Male | 39 | CBT psychotherapist |

| 19 | Female | 48 | REBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 20 | Female | 47 | Horney analytical psychotherapist |

| 21 | Female | 46 | CFT psychotherapist |

| 22 | Male | 43 | Analytical psychotherapist |

| 23 | Female | 31 | CFT psychotherapist |

| 24 | Female | 30 | CBT psychotherapist |

| 25 | Female | 31 | Psychoanalyst based on self psychology |

| 26 | Male | 45 | CBT psychotherapist & professor |

| 27 | Male | 36 | Intensive short term dynamic psychotherapy |

| 28 | Female | 34 | ACT psychotherapist |

| 29 | Female | 34 | EFT psychotherapist |

| 30 | Female | 43 | Dialectical behavior therapist |

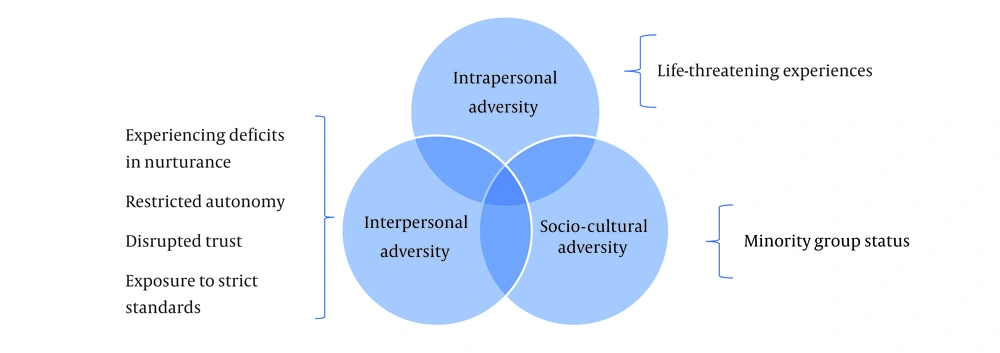

The extracted overarching theme was “Tripartite Adversities Involved in the Formation of a Lack of Self-acceptance”, which consists of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-cultural adversities (Table 1). These themes are not entirely distinct from one another. They reflect the pervasive unmet developmental needs of individuals and intense experiences that hinder the formation of a healthy sense of self, ultimately leading to a lack of self-acceptance in the relevant areas (Figure 1).

4.1. Intrapersonal Adversity

Intrapersonal adversity is closely tied to the core of individuals and relates to experiences that threaten their physical and existential safety. Existential insecurity encompasses events, environments, and primary relationships that can lead to feelings of vulnerability and insecurity. One participant provided a significant example:

“I had always had headaches until my therapist suggested documenting when they occurred, and I realized I had a feeling of insecurity every time. My therapist helped me stay with my emotions. I discovered I was unconsciously contracting my scalp, which caused the headaches... I remembered a childhood memory when the city was bombarded during the war. It was terrifying…” (P1).

Another participant shared: “When I was a child, I was ill and had to undergo a life-threatening surgery right away. I thought I might die!” (P6). The common theme in all these examples is the issue of life and death, which strongly impacted their sense of physical security in the following years of their lives.

4.2. Interpersonal Adversity

Interpersonal adversities arise in relationships with particularly significant others and are more outwardly visible than intrapersonal experiences. These adversities include the subthemes: Deficits in nurturance, restricted autonomy, disrupted trust, and exposure to strict standards. Regarding deficits in nurturance, being deprived of adequate physical and emotional care in childhood is one reason individuals may feel unworthy of receiving love. One participant stated:

“After becoming exhausted from attachment to my partner, I focused on my emotions and realized I was evoking mothering behavior in her… I remembered that my mother would stay late at work, and I could not find anything to eat at home during my childhood…” (P18).

Another participant shared: “I lost my father, and my mother left me at my grandfather’s house after she remarried. I think this was the reason I always sought love and care from others” (P20). The participants' remarks highlight insufficient nurturance as a significant factor leading individuals to seek affection and love, which ultimately results in an impaired sense of self-worth and a lack of self-acceptance.

Suppressed autonomy refers to experiences in which individuals encounter situations that limit their ability to exercise autonomy and make independent decisions. These experiences can strongly affect the development of self-acceptance. One participant remarked: “I was prohibited from going out with my friends. My father would say they were not worthy of my time. I also remember that my mother always answered questions asked of me; I felt I had no space to express myself. Everything was pre-determined, and there was no sense of agency. I hated myself for not being able to claim my "truth"…” (P25). Another participant shared: “My parents lost their first child, and they used to overprotect me” (P24).

In this theme, the participants explained that the constant feeling of being under surveillance made them susceptible to inner suffocation and created a strong desire for private space, independence, and freedom. However, due to their parents' interference in their lives, they were unprepared for independence.

Regarding disrupted trust, childhood abuse, whether physical or emotional, has detrimental effects on children’s perception of themselves and others, disrupting their ability to trust. When children’s vulnerabilities, love, and desire to please their parents are exploited, not only is their self-image impaired, but these manipulations also lead to a disruption of trust in others, as shown in the following quotes:

“I always felt like people wanted to take advantage of me, so I couldn’t establish relationships. I had a deep-seated feeling of ‘being bad,’ even though I pretended to be trustworthy. During therapy, I realized that my feelings were related to my parents’ misconducts, such as being deceived and being physically punished” (P12).

Another participant said: “I think it was because I had to work and help my father cash his checks” (P21). These victims of abuse had internalized the negative behaviors of their parents and were unable to accept themselves as they were.

The subtheme exposure to strict standards addresses the presence of excessively strict authority figures in family or educational settings. The participants’ responses revealed that they were under pressure to meet impossibly high standards, which emphasized perfection in appearance and achievement. Failing to meet these standards led them to feelings of worthlessness.

One participant said: “My mother was constantly analyzing everyone’s appearance, and my father constantly compared me to those who were successful” (P2). Another participant said: “The teachings we were given about envy and other sins made me deny, rationalize, or criticize myself unconsciously after committing them” (P5). Moreover, another participant said:

“My parents expected me to be better than other children because they worked much harder than other parents. Sometimes my dad would say, ‘We gave you everything you wanted, and that’s why we expect more from you’” (P17). The constant comparison to others and the high expectations placed on them contributed to a distorted sense of self-worth, leading to difficulty in accepting themselves.

In this subtheme, there is significant emphasis on achieving high standards. This way of raising individuals directly contributes to creating an environment with little room for mistakes, individuality, or intrinsic motivation. Moreover, in this subtheme, performance is valued more than the individual, so if someone fails to meet those standards, they feel extremely worthless.

4.3. Socio-cultural Adversity

This theme reflects how social and cultural conditions influence one's relationship with themselves. The subtheme “Minority Group Status” addresses the challenges faced by individuals belonging to minority groups due to their linguistic, religious, physical, or ideological differences. Discrimination, social exclusion, and individuals' internalized expectations of being excluded can hinder the formation of a healthy sense of self, leading to a lack of self-acceptance. One participant said: “My mother was from a village and was never able to learn the manners of life in a city... I tried to compensate for that by being extremely perfectionistic” (P8). Another participant said: “We were a religious minority and were often harassed by some of our fellow citizens” (P5). It appears that people in minority groups often find themselves in a position where the stigma of feeling "they do not belong" makes it more difficult for them to accept themselves as they are. As a result, they must make an active, extra effort to fit in and belong.

5. Discussion

This study identified that the lack of self-acceptance is a complex and multifaceted construct, consisting of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-cultural aspects. Experiencing adversities such as “existential insecurity,” “experiencing deficits in nurturance,” “restricted autonomy,” “disrupted trust,” “exposure to strict standards,” and “minority group status” can lead to a lack of self-acceptance, which may, in turn, result in perfectionism, self-criticism, and shame.

As examined in this research, experiencing life-threatening events led individuals to avoid certain aspects of themselves or their inner experiences. Life-threatening experiences, being matters of life and death, are an intrapersonal phenomenon. While earlier studies and theories have highlighted the impact of traumatic experiences on overall personality development and identity formation, the role of "life-threatening experiences" as a direct and primary cause of the lack of self-acceptance has not been specifically identified. However, Darwin, Freud, and many others have argued that all beings are instinctively driven toward self-preservation and the continuity of experience.

Interpersonal adversities reflect the role of relationships with significant others in the formation of a lack of self-acceptance in the following ways. Firstly, regarding deficits in nurturance, the findings demonstrate that inadequate attention to physical and emotional needs by primary caregivers can play a significant role in the development of a lack of self-acceptance. This is consistent with Bowlby's notion of a secure base, which emphasizes the critical role that early caregiving plays in the development of a healthy self-concept, in turn affecting people's capacity to seek out and offer care to others (31). Gilbert (32) argues that individuals with such deficits are highly sensitive to signs of abandonment. One of their common fears is that their loved ones will reject them, leading them to constantly demand love, appreciation, and approval. This behavior pushes people away and manifests as uncomfortable attachment patterns and relationship dynamics. Moreover, deficits in nurturance lead to negative reactions when facing situations that require compassion and care (33), particularly in individuals with high levels of self-criticism and shame (34).

Secondly, this study supports the notion that restricted autonomy, resulting from excessive support, control, and protection from parents, hinders individuals' sense of autonomy. This issue alone can impact their self-acceptance. As a result, instead of developing a healthy and acceptable sense of self, they tend to have negative self-evaluations, behave negatively toward themselves (35), become overly dependent on their parents, and feel vulnerable and inadequate when faced with the real world (36).

Thirdly, regarding disrupted trust, our findings indicate that parental misconduct during childhood is associated with a lack of self-acceptance in individuals and their unhealthy relationships, which supports previous findings (37). Since children pick up on both verbal and nonverbal cues from their parents, their behaviors can significantly impact the child's development (38). As “the reactions of those around us are the biggest driver of our self-image” (39), such parental misconduct has long-lasting effects.

Lastly, regarding exposure to strict standards, our results show that evaluating children based on their performance leads to uncertainty about the adequacy or goodness of any efforts they make. This gradually cultivates performance-dependent self-worth. This attitude results in the conceptualization of the self as defective and not good enough (40, 41), ultimately leading to a lack of self-acceptance. In summary, this research supports the idea that interpersonal relationships contribute to the development of a lack of self-acceptance in various ways.

Regarding socio-cultural adversities, minority group status (i.e., belonging to ethnic, religious, or physical minority groups) inherently leads to a sense of not belonging and forms the basis for a lack of self-acceptance. Most research on self-acceptance focuses on how it develops within minority groups (42, 43). Since individuals in minority groups are often victims of prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination, their self-worth is impacted through mechanisms such as reflected appraisal and social comparison (44).

In conclusion, the findings revealed that the lack of self-acceptance may originate from adversities in three main areas: Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-cultural adversities. That is, the way individuals' inner world, interpersonal relationships, and the cultural context they exist in contribute to the development of a lack of self-acceptance. This suggests that an individual’s well-being is inextricably linked to the healthy dynamics of both family and society.

It is important to note that interviewing psychologists who have also experienced a lack of self-acceptance allowed for a more thorough investigation of the phenomenon, which is crucial for cultivating a deeper understanding of this issue. However, interviewing psychologists exclusively may have limited the applicability of the findings to other contexts. The profession and field of psychologists may lead to a profession-based narrative of their lived experiences with low self-acceptance, making it impractical to generalize to the broader public. Future research could examine the perspectives of individuals from diverse backgrounds and disciplines.