1. Background

Schizophrenia is recognized as a chronic mental disorder, though it may actually represent a spectrum of disorders with diverse origins, affecting individuals with varying clinical symptoms, treatment responses, and disease courses (1). Schizophrenia spectrum disorders impact over 21 million people worldwide, with approximately seven out of every 1000 individuals expected to develop such disorders during their lifetime (2, 3). The signs and symptoms of schizophrenia vary widely and include alterations in perception, emotion, cognition, thought processes, and behavior. This disorder is closely linked with significant impairments in functional, social, occupational, and educational domains (4). More than 90% of individuals with schizophrenia are unable to live independently and require continuous care across many aspects of their lives. The disorder not only affects patients but also has a profound impact on their family members (5).

The family is the primary social unit in which a person's personality is shaped (6). It acts as a social system that provides emotional, physical, and intellectual support to its members, promoting their development, character formation, and subsequent adaptation to life challenges (7, 8). Among the many roles families play, the most critical include offering support, meeting emotional needs, and fostering mental well-being (9). In general, families take on the responsibility of caring for their members in physical, emotional, social, and economic terms. The quality of family structure and the relationships between its members significantly influence the likelihood of mental disorders emerging in the future (10).

Family support refers to the individuals who directly or indirectly interact with the person and offer assistance. Family members represent one of the most vital components of an individual's social network, providing support that is unmatched by any social institution. This support is characterized by its desirability, accessibility, strength, and quality, promoting positive supportive behaviors. Family support plays a critical role in addressing the challenges of schizophrenia, enabling patients to focus on overcoming barriers to family involvement (11). Family support involves both the characteristics of the support provider and the recipient, as well as the supportive nature of the environment. This network can be visualized as concentric circles, with the individual at the center, closely supported by family in an inner circle, and more distant acquaintances positioned in outer circles (12, 13).

The provision of family support, given its dynamic and ongoing nature, presents significant challenges, particularly in the context of individuals with mental disorders (14). The World Federation of Mental Health has identified the responsibility of those supporting and caring for schizophrenia patients as a global concern. This recognition stems from the demanding nature of continuous care, which requires a sustained combination of energy, knowledge, empathy, and financial resources. The impact of this caregiving extends beyond the well-being of the patient, affecting the caregivers' daily lives. Many struggle to balance work, family responsibilities, and patient care, often neglecting their own physical and mental health in the process (15, 16).

2. Objectives

Given the critical role of family support in improving outcomes for schizophrenia patients, and the associated challenges—especially in countries like Iran, where social workers or home nurses do not provide continuous follow-up after hospitalization and families are left to manage patient care—this study aims to explore the obstacles hindering family involvement in supporting individuals with schizophrenia.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This study employed a qualitative methodology, using semi-structured face-to-face interviews to capture in-depth perspectives from participants. Content analysis was used to explore the rich textual data generated by these interviews. This approach was chosen due to the limited existing knowledge about family perspectives on the challenges of providing sustained support to individuals with schizophrenia. By employing this methodology, the study aimed to gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the various dimensions of family support from the participants' viewpoints.

3.2. Setting and Participants

A total of 20 families (n = 20), consisting of caregivers for individuals with schizophrenia who had provided informed consent, were recruited for the study. Participants were selected based on their experience with the caregiving process, their willingness to participate in the research, and their ability to articulate their experiences. Data collection occurred between February and November 2023.

The researcher, a nursing Ph.D. student trained in qualitative research methodologies, led the study and ensured reflexivity by continuously comparing and analyzing emerging concepts. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the family member had a relative diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders according to DSM-5 criteria; (2) the family member had spent at least 31 hours per week for three months providing care to the diagnosed patient; (3) the family had consistently supported the patient for at least three years; and (4) the participant could verbally communicate personal experiences, feelings, and perceptions. Exclusion criteria included unwillingness to participate at any stage of the study and cognitive impairment that prevented informed consent.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This study is part of an ongoing doctoral research project titled "explaining the process of ongoing family support in schizophrenia patients." Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee at the University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1401.166). Prior to participation, all individuals were fully informed about the study’s purpose and procedures. Participants provided written informed consent, ensuring transparency and adherence to ethical standards throughout the research process.

3.4. Interview and Data Collection

To design a semi-structured interview guide, the researcher conducted an extensive review of the relevant literature and consulted mental health professionals for expert feedback. Interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed to ensure accuracy. The guide was structured around broad themes aligned with the study’s objectives, and specific probes were developed to explore participants’ experiences in more detail. Expert consultations also informed the refinement of the guide.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted using open-ended questions in a semi-structured format. The interviewer employed a conversational approach, allowing for flexibility and the exploration of topics that participants deemed significant. Before the interviews, confidentiality guidelines and the importance of voluntary participation were explained, with an emphasis on respect and the secure handling of personal information. To ensure anonymity, participants were assigned numbers rather than names.

Each interview lasted between 40 to 60 minutes, during which probes were used to clarify and expand upon participants' responses. Interviews continued until data saturation was reached, meaning no new information significantly altered the study’s findings. Following the interviews, demographic information was collected. Key open-ended questions used to identify challenges included:

- "What obstacles have you encountered in providing support?"

- "How have you addressed or overcome these obstacles?"

3.5. Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted simultaneously using MAXQDA 2020 software to effectively organize and compare the data. Each interview transcription underwent a thorough review, and qualitative data analysis followed the Lundman and Graneheim method. This process included transcribing each interview, reading and rereading the content to fully understand its essence, and immersing in the data to extract meaningful insights.

After familiarization with the data, the next steps involved identifying meaning units and summarizing them, extracting initial codes, organizing similar codes into subcategories, grouping related codes into broader categories, uncovering both manifest and latent concepts, and finally, developing overarching themes (17).

To achieve the research objectives, interview transcriptions were meticulously reviewed multiple times. Meaning units were identified based on research questions, and corresponding codes were assigned. Preliminary codes were then clustered into subcategories based on conceptual similarities. These subcategories were compared and organized into broader main categories to develop an abstract framework. The main categories were then further refined into more abstract concepts called subcategories. All extracted codes and categories were reviewed and approved by the second and third authors of the study.

Continuous data analysis and comparison were conducted to reduce the initially extracted codes, leading to the abstraction of categories and subcategories. The Lincoln and Guba criteria—credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability—were employed to maintain the reliability and validity of the data (18).

To ensure credibility, participants were invited to validate the extracted interview codes and provide feedback as needed, a process known as member checking. Data-source triangulation was employed by conducting interviews with family caregivers of various relationships to the patient, ethnic backgrounds, and religions to strengthen credibility. Peer checks were conducted by the second and third authors to confirm the findings, and a faculty member from outside the research area performed a faculty check to review and validate the interview texts, codes, and categories.

To ensure dependability, every stage of the study was meticulously documented. Maximum variation sampling was used to select participants, considering factors such as ethnicity, education level, economic status, relationship to the patient, and social class, thereby enhancing the study's applicability across diverse contexts.

4. Results

4.1. Participants' Socio-demographic Characteristics

Twenty participants were recruited for the study, including family members (3 fathers, 7 mothers, 1 brother, 1 sister, and 1 wife) and 7 healthcare team staff. All participants met the study criteria and expressed a willingness to participate in the interviews. Among the individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, 9 were male, and 11 were female. Additionally, 3 patients had concurrent physical conditions, including leg deformity, claudication, pituitary gland issues, and underdeveloped ovaries. The duration of time these patients had lived with their families ranged from 3 to 19 years (Table 1).

| No | Age | Marital Status | Educational Status | Relationship with Patient | Years of Caregiving | Physical Illness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | Married | University | Father | 3 | - |

| 2 | 53 | Married | Middle school | Father | 3 | - |

| 3 | 45 | Married | Middle school | Spouse | 10 | - |

| 4 | 32 | Single | University | Brother | 12 | - |

| 5 | 48 | Married | Middle school | Mother | 4 | - |

| 6 | 68 | Married | No formal education | Mother | 17 | Leg deformity |

| 7 | 42 | Married | University | Mother | 9 | - |

| 8 | 65 | Married | Middle school | Mother | 4 | Claudication |

| 9 | 40 | Married | University | Mother | 8 | - |

| 10 | 70 | Married | Primary school | Father | 10 | - |

| 11 | 45 | Married | High school | Mother | 15 | - |

| 12 | 43 | Single | University | Sister | 19 | Pituitary gland issues |

| 13 | 54 | Married | Middle school | Mother | 13 | Underdeveloped ovaries |

| 14 | 46 | Married | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

| 15 | 43 | Married | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

| 16 | 38 | Married | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

| 17 | 39 | Married | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

| 18 | 35 | Single | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

| 19 | 30 | Single | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

| 20 | 33 | Married | University | Healthcare provider | - | - |

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Challenges for Ongoing Family Support

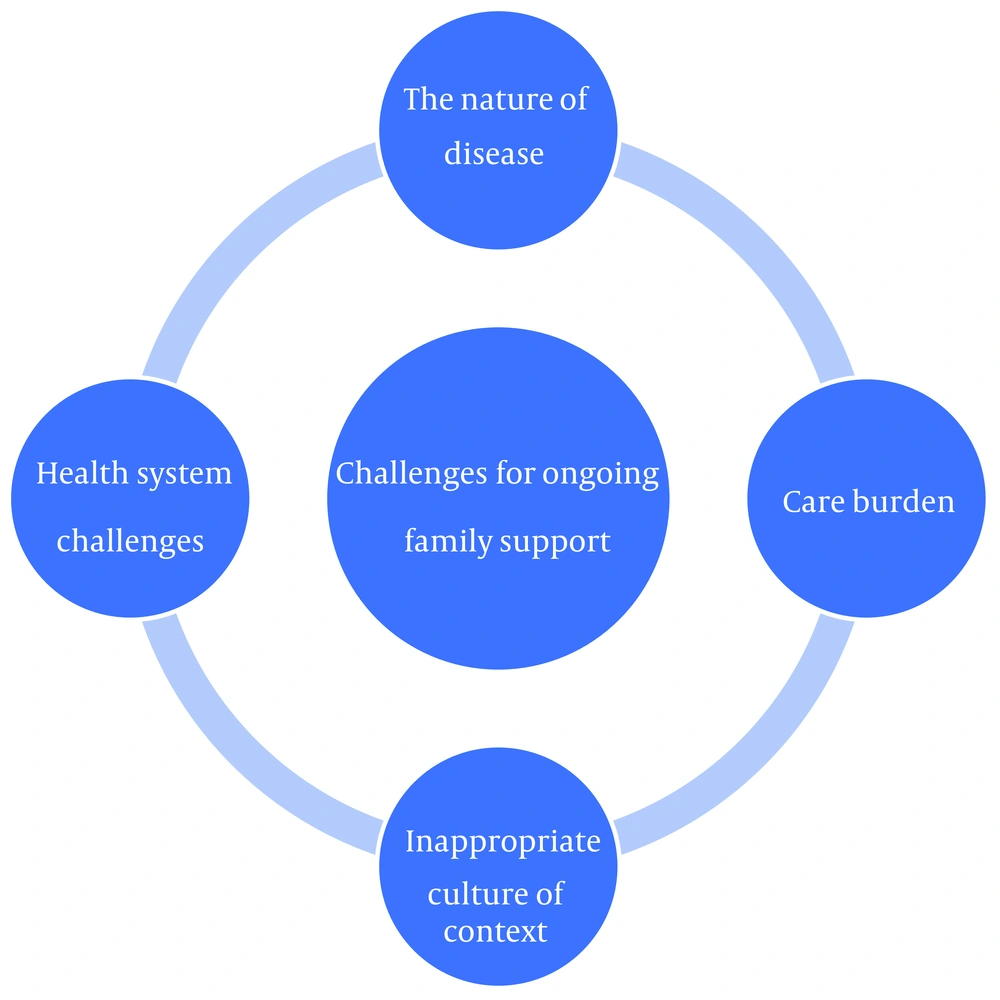

An iterative data analysis process revealed four main categories concerning the "challenges for ongoing family support" (Figure 1 and Table 2).

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| The nature of the disease | Aggression; swearing; inappropriate appearance of the patient; suicide; running away from home; patient's compliance noncompliance with medication |

| Care burden | Family exhaustion; fear of consequences of monitoring; family mental fatigue; the financial burden of care |

| Inappropriate culture of context | Rejection of the patient by society; mockery of the patient in the community; challenges in neighborhood relationships; social stigma |

| Health system challenges | Difficulty in accessing medication; limited access to physicians; insufficient support for the family |

Categories and Subcategories Extracted From the Data

4.2.1. The Nature of the Disease

The nature of schizophrenia posed significant challenges to sustaining family support. This category referred to the inherent characteristics of the illness that complicated caregiving. It included issues such as aggression, swearing, inappropriate behavior, suicidal tendencies, running away from home, and noncompliance with medication.

Caregivers frequently reported difficulty managing the patient's aggression toward family members, which often made caregiving unsustainable. One participant shared, "He would pick fights at school, pick fights at home. Anything in the house, he would break. They would smash all the glasses and everything we have." (P-6).

Swearing was another common issue that disrupted family support and treatment. One caregiver described, "For example, we would go to a party, he wouldn't say hello, wouldn't inquire about anyone's well-being, wouldn't shake hands with others; he would start speaking badly and swearing. When we took him to the doctor, he would get worse, hit and swear, asking why did you take me to the doctor, am I crazy?" (P-2).

The patient's inappropriate appearance, such as undressing at home and going onto the balcony naked, added to the challenges, leading to the patient being confined at home. This caused embarrassment and discomfort for the family members tasked with monitoring the patient. One caregiver explained, "He didn't realize it himself. He would say, 'You are my family, what's wrong with me being naked?' He would go naked onto the balcony." (P-7).

The patient's suicide attempts caused feelings of despair and hopelessness in the family, leading them to question the effectiveness of treatment. One participant described, "Not long ago, we took him to the doctor for kidney pain. When we returned, I wasn't home. He had taken all the medications related to my high blood pressure and consumed them. He had also cut the veins on his hand with a knife." (P-8).

Some families reported that the patient's repeated attempts to escape from home made it difficult to continue treatment and monitor medication adherence. One caregiver shared, "He escaped from home several times; the police caught him. We went to the police station, brought him back, followed up on his case, and took him to the hospital again." (P-13).

In most cases, families expressed frustration over the patient's failure to take medication as prescribed and non-compliance despite their best efforts. One participant explained, *"He never takes his medication on time; we have to force it on him. Sometimes he refuses to take it."* (P-10).

4.2.2. Care Burden

Another significant obstacle to sustaining family support was the care burden. This refers to the physical, emotional, and financial challenges caregivers face when supporting individuals with chronic illnesses or disabilities. This category included issues such as family exhaustion, fear of consequences from monitoring, family mental fatigue, and the financial burden of care.

As schizophrenia is a chronic illness, caregiving becomes a long-term responsibility. In most cases, families bear the full weight of this responsibility, leading to exhaustion. One participant explained, "Practically, because families are very much alone, they get tired. These families are exhausted. For example, we had a case of schizophrenia for 20 years, and the family always took care of him, bringing him back to the hospital for treatment. Well, the family was extremely tired." (P-14).

The fear of consequences related to monitoring the patient, such as fear of hospitalization, was another concern. Families often expressed anxiety about their loved ones deteriorating like other patients they encountered in hospitals. One participant shared, "On the other hand, when I came to the hospital and saw other patients, my heart sank. I was scared and kept saying to myself, 'I hope my child doesn't reach this point.' I was really afraid of some patients." (P-7).

After their child was diagnosed with schizophrenia, families frequently experienced ongoing concerns, leading to mental fatigue and further increasing the care burden. One participant explained, "I'm always afraid and think to myself, 'I hope he doesn't end up like those two kids who had an accident and died. I hope he doesn't die too.' " (P-8).

Due to the patient’s need for ongoing and diverse treatments, families often faced high treatment costs. Additionally, family members directly involved in the patient’s care often fell behind in their work, further exacerbating the financial strain. "Economically, because I don't have income that way, and because I have to spend a lot of time following up on the patient's treatment, I feel pressured." (P-2).

4.2.3. Inappropriate Cultural Context

An inappropriate cultural context was another identified obstacle, referring to societal attitudes and misconceptions about schizophrenia. This category includes the rejection of the patient by society, mockery within the community, strained neighborhood relationships, and the impact of social stigma.

There is a general lack of trust and acceptance in society toward individuals with schizophrenia, resulting in limited social interactions and family visits. These patients are often marginalized. One participant shared, "For example, he goes to the local store alone, and the shopkeeper either refuses to sell him items or calls me; I must be with him." (P-7).

Patients with schizophrenia, who may lack insight into their condition, sometimes talk about their delusions and hallucinations, leading to mockery by community members. "Even childhood friends, when they see him, mock him and throw their hands up, saying, 'How are you, God?' " (P-7).

The nature of the illness also strained relationships with neighbors. Patients' inappropriate behaviors often led to pity or complaints from neighbors, forcing families to move homes. "Neighbors would add salt to the wound, saying, 'Oh my God, poor thing.' The pity they felt worsened my situation, making my already difficult circumstances even more challenging." (P-11).

Social stigma further complicated the situation, with families being labeled as "crazy" due to their association with the patient. This stigma led to feelings of rejection and embarrassment. One participant noted, "They say, 'Poor family, their child is sick, gone crazy.' " (P-8).

4.2.4. Health System Challenges

Health system challenges emerged as significant obstacles to sustaining family support. This category encompasses issues related to the high cost of treatment, difficulty in accessing medication, limited access to physicians, and insufficient support for families.

The high cost of treatment was a major barrier, primarily due to the lack of adequate health insurance, the expense of psychiatric visits, and the high fees for non-drug treatments such as psychology and occupational therapy. One participant noted, "I can't even afford his doctor's expenses anymore. The cost of his doctor's visits is high." (P-6).

Another challenge was the difficulty in accessing necessary medications, exacerbated by time constraints and the lack of timely availability of drugs. "Finding the medication and sending it from Turkey to Iran is very difficult. Finding the medication has become very difficult for me. Today, I went to several pharmacies to find my son's medication; this is a big problem for me." (P-1).

Delayed access to physicians or difficulties resulting from the migration of doctors who had been treating the patient were also mentioned as significant hurdles. One participant shared, "I used to take him to the doctor regularly, and we always went on time for all the visits until his doctor left the country. We couldn't take him to the doctor again for a long time, and after that, we went around searching until we found another doctor." (P-12).

Furthermore, the lack of an effective family support system at the societal level was a critical issue. Families expressed feeling isolated and without the necessary support, despite their urgent need for assistance. One participant emphasized, "One of their most important issues and problems is that they are alone in this society. It's like having a cancer patient who needs expensive medications and doesn't have a support system. Well, how can the family alone cover the financial burden of these medications?" (P-14).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the obstacles that hinder the continuity of family support for patients with schizophrenia. Four main categories of challenges were identified: (1) the nature of the disease; (2) the caregiving burden; (3) the inappropriate cultural context; and (4) challenges within the health system. These findings provide insight into the complex barriers that families face in maintaining ongoing support for individuals with schizophrenia.

The unpredictable symptoms of schizophrenia impose a significant emotional and physical toll on families, making it difficult to sustain long-term care. The caregiving burden, including emotional stress and potential burnout, further complicates the situation. Cultural factors, such as the stigmatization of mental illness, deter families from seeking necessary support due to societal taboos. Additionally, deficiencies in the healthcare system, including limited access to mental health services and inadequate resources, place an additional burden on families trying to navigate the complexities of schizophrenia care. Recognizing and addressing these challenges is essential for developing comprehensive strategies to strengthen family support for those managing schizophrenia.

5.1. The Nature of the Disease

Previous qualitative studies have demonstrated that many caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia, when confronted with symptoms such as social withdrawal, neglect of personal hygiene, irritability, aggression, and non-adherence to medication, often experience a sense of despair during the treatment process. This hopelessness can disrupt the continuity of care (19-21). The findings of this study align with previous research, as caregivers cited behaviors like aggression, swearing, inappropriate appearance, and non-compliance with medication as key obstacles to maintaining continuous care.

Participants in this study highlighted several examples, such as patients escaping from home or refusing to take their medication, which led to the discontinuation of their treatment. Additionally, caregivers noted that patients often displayed aggressive behavior or used offensive language during the administration of medication or visits to healthcare providers, further complicating their ability to manage care.

5.2. Care Burden

Families of patients with schizophrenia often face a significant caregiving burden, encompassing emotional, physical, and financial aspects, which can negatively impact their ability to provide sustained support (22-24). The findings of this study align with these earlier studies, demonstrating that family fatigue, for example, arises from repeated follow-ups, frequent hospital visits, and ongoing monitoring of the patient's medication, which typically requires long-term use. In this study, these factors were linked to the physical burden of caregiving. Additionally, emotional stress resulting from cognitive fatigue—such as concerns about the patient’s mental incapacitation, fears of suicide, and the emotional strain of caregiving—further exacerbate the burden. The financial strain associated with caregiving, including the costs of medication, doctor visits, hospitalizations, and non-pharmacological treatments like therapy or occupational therapy, also plays a significant role in intensifying the overall caregiving burden.

5.3. Inappropriate Cultural Context

Social stigma adds psychological pressure and despair within families (25). Faced with social rejection, individuals with schizophrenia and their families often experience a reluctance from others to engage with them, leading to isolation and distancing from relatives and neighbors. Society frequently responds to these individuals and their families with aggression, judgment, and mockery, further violating their rights and deepening their sense of humiliation and alienation (26-30). The societal stigma, social ostracism, and challenges in neighborhood relationships contribute to the frustration and despair experienced by families, thereby hindering their ongoing support for treatment. The current study supports these findings, showing that societal rejection, ridicule, social isolation, and neighborhood conflicts create significant barriers to sustaining family support.

5.4. Health System Challenges

Research indicates that financial burdens and a lack of adequate social support are significant challenges faced by families of patients with schizophrenia. Effective professional support and financial assistance are crucial for helping families adapt to the demands of caregiving (31). To alleviate the financial and social burdens associated with schizophrenia, broader healthcare policies are required within national healthcare systems. The chronic nature of schizophrenia leads to extensive treatment costs, necessitating support from healthcare organizations and the community. Schizophrenia relapse is especially costly, and the early onset of the condition has considerable economic implications, including job loss and the need for inpatient services, specialized community residences, and family caregiver support (32, 33). The findings of this study align with these prior studies, demonstrating that health system challenges, such as high treatment costs and inadequate support for families, exacerbate the burden of caregiving. Therefore, adequate support from relatives, friends, neighbors, and acquaintances—as well as from organizations and healthcare systems—appears essential.

A limitation of this qualitative research is that participants may have withheld certain experiences due to personal or social considerations. Additionally, the findings may not be broadly generalizable due to the specific cultural context in which the study was conducted.

5.5. Conclusions

Given the chronic nature of schizophrenia, the long-term treatment requirements, and the considerable caregiving responsibilities for those affected, fatigue and caregiving burdens become inevitable. To address these challenges, community-wide awareness campaigns about the nature of schizophrenia and the specific needs of affected individuals are essential. Promoting accurate, scientific information can raise public awareness and foster more appropriate societal responses. Cultural initiatives aimed at reducing discrimination and encouraging active engagement with individuals affected by schizophrenia, along with workshops and educational sessions, can help shift societal perspectives toward greater empathy and understanding.

Additionally, financial support for caregiving families is crucial in alleviating the financial pressures associated with the long-term treatment and care of individuals with schizophrenia. Enhancing access to healthcare services, both for patients and their families, and facilitating psychological counseling and non-pharmacological treatments are key to improving overall support. Strengthening community support programs aimed at skill-building and managing caregiving-related fatigue will significantly reduce the burden on families, thereby ensuring sustained family support for individuals living with schizophrenia.

Implementing these recommendations can improve community support, alleviate caregiving pressures, and ensure ongoing family support for those coping with schizophrenia.

5.6. Study Recommendations

Future research should explore the impact of cultural and family structure on the provision of family support for patients with schizophrenia. Additionally, research on family support for other mental disorders is recommended.