1. Background

The increasing birth rate has become a significant political concern in Iran, linked to potential challenges posed by a future decline in population growth and insufficient availability of young human resources in the economy (1). Population growth, which contributes to increased political power, is closely linked to women's role in childbearing. Fertility is inseparably connected to the role of women in society, and changes in women's status can significantly influence their reproductive behavior (2).

Pregnancy is a physiological process characterized by extraordinary interactions and a significant increase in sensitivity, during which the line between health and disease becomes narrower. The physiological and psychological responses experienced during each pregnancy can vary; emotions such as happiness, disgust, anger, anxiety, fear, and depression may be observed (3). Many women perceive pregnancy as a stressful factor, often referring to it as a life crisis that disrupts the biological-psychosocial balance of the woman. This period also brings changes to roles within the family and workplace, while establishing the parental bond between the mother and baby (4). Completing the pregnancy process in a healthy manner is a "human right" for every woman. Protecting, maintaining, and improving the health of both mother and fetus is essential (5).

One of the most significant factors affecting both fertility and population growth is women's employment and their participation in the workforce. The efforts of working women to integrate, organize, and balance various natural roles simultaneously place them under considerable pressure (6). It makes work-life balance difficult for them, as they have to juggle two full-time jobs — one at the office and one at home (7). As a result of the inconsistency between family and occupational role expectations, along with gender discrimination in the workplace, women have attempted to postpone or refuse to have children (8).

There is a category of working women, specifically faculty members, who face numerous challenges due to their multiple occupational roles, including educational, research, cultural, and executive responsibilities. These challenges significantly impact their maternal role in motherhood (9). Heavy workloads, juggling multiple roles, and the lack of mental downtime after working hours contribute to ongoing mental stress (10). The interweaving of work and life, along with the broad range of intellectual, educational, research, and scientific conflicts in their geographical work area, complicates the balance between work and family (11), especially motherhood for female faculty members (12).

Additionally, the timing of childbearing, which is constrained by women's reproductive age and the early years of child-rearing — when a child is dependent on the mother — adds to the difficulty. This need for increased time and attention from the mother conflicts with the time constraints faculty members face to demonstrate their scientific competence and earn necessary points for transitioning from contractual to permanent employment status, as well as for promotion (13). The highest interference of family duties with job duties in female academic staff members related to maternal affairs has been reported. A study by Rodino-Colocino et al. showed that the number of mothers who are faculty members is low (14). Furthermore, research by Ollilainen on pregnancy and its perception among female faculty members revealed that they believe pregnancy can still be viewed as an anomaly in the university setting. This perception creates a tension between work, family, and bodily duties that can affect their success or failure compared to the "ideal university person" (12).

Therefore, supportive policies can help create a positive experience for them in having children (15). These women represent an educated population with significant influence in society, and their experiences are very important to shape supportive policies (16). Therefore, it is important to examine the challenges and problems of faculty members of this valuable scientific resource on pregnancy and the affairs after. Although some researchers consider women's employment as a factor that removes mothers from marital and maternal duties, some researchers believe that the presence of women in society will lead to the development of both women and society (17). Therefore, adopting the strategy of not having children or having only one child due to the right to work is as problematic from an economic and political point of view as adopting the approach of returning home and leaving social activity. This situation has highlighted the need to develop workplace policies that protect women, especially during pregnancy.

Additionally, policy-making and any planning to increase fertility levels require comprehensive and deep knowledge of women's reproductive actions and their lived experiences. Given that faculty members are crucial elements of higher education and play an important role in the transfer and production of knowledge, understanding their status can be beneficial for researchers, policymakers, and planners. According to the literature review, no study was found on the challenges faced by medical faculty members in relation to pregnancy. Without understanding these experiences, it is challenging to implement effective, evidence-based policies and support programs for working women in academia. Considering that phenomenology provides a deep understanding of mental experiences and is an ideal approach to explore the subtle physical, emotional, and social aspects of pregnancy among working women (18), the researcher intends to explore the experiences of female medical faculty members during pregnancy through this qualitative research.

2. Objectives

This study aims to explore and describe the lived experiences of female faculty members during pregnancy in Iran using a phenomenological approach.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The present study employed a qualitative design using the phenomenological method, with an emphasis on Max van Manen's phenomenological research methods, to understand and explain the lived experiences of female medical faculty members during pregnancy. This phenomenological approach seeks to uncover mental or emotional meanings, demonstrating that individuals who experience the same life event may ascribe different or similar meanings to it. Although people may find themselves in similar situations, experiencing a single phenomenon, they often reflect on their experiences in diverse ways and assign distinct meanings to them (19).

3.2. Study Participants

The research was conducted at Dezful University of Medical Sciences, where female medical faculty members were employed from May 2023 to August 2023. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method among faculty members who met the inclusion criteria, which included being a faculty member and having experienced pregnancy. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate in the study and inability to articulate their understanding. Diversity in participant selection was achieved in terms of age, educational status, and number of pregnancies, allowing the researcher to gain a comprehensive understanding of the experiences.

3.3. Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected through interviews. Participants were asked to describe their lived experiences, including their perceptions, thoughts, and feelings during pregnancy. The interviews aimed to uncover the lived experiences of female faculty members during pregnancy. The interview commenced with the question, "How did you spend your pregnancy?" It then proceeded with questions such as "What problems did you encounter?" and "What were your working conditions?" Additionally, follow-up questions like "Can you provide a specific example?" "What do you mean?" and "How?" were asked based on participants' responses. Alongside conducting unstructured interviews, close observation without intermediaries was employed, supplemented by field notes and annotations (e.g., participants' posture or other situations not captured by the tape recorder).

3.4. Data Analysis

Each interview lasted approximately 35 minutes on average, continuing until data saturation was achieved. This was determined when participants' statements no longer contributed new codes to those extracted from previous interviews. The Van Manen analysis method was employed in this study, involving several steps: Reflecting on the lived experiences of female faculty members, formulating a phenomenological question, considering prior knowledge of the method, engaging in medium-term communication with faculty women through repeated visits to their offices, conducting semi-structured interviews, listening to and transcribing interview audio files, immersing in the data, analyzing texts line by line, extracting themes, and writing the main text of the article (20). Data analysis was conducted manually.

To ensure the accuracy and trustworthiness of the data, Lincoln and Guba's criteria were applied (21). For dependability, prolonged engagement and member checks were utilized, employing multiple data generation methods, including interviews and field notes. Confirmability was achieved through thick description and an audit trail, with the research process thoroughly documented. For transferability, detailed descriptions of the research context, transcripts, and observed processes were provided to facilitate judgment and evaluation by others regarding the results' transferability. Credibility was ensured through member checks, where the derived themes were returned to participants for validation as their experiences of maternal roles and pregnancy. All subjects approved the themes. Additionally, data coding and analysis were conducted independently and collaboratively by the researchers to ensure consensus on the topics.

In terms of reflexivity, it is important to note that the researcher was also a participant in the study's subject matter. While efforts were made to minimize personal biases during data collection and analysis, the researcher acknowledges the challenge of achieving complete objectivity. To enhance the credibility of the findings, the data analysis was reviewed and validated by a fellow researcher with extensive experience in qualitative research. This collaborative approach aimed to mitigate potential biases and ensure a more nuanced interpretation of the data.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

All ethical considerations in human research, including informed consent, permission to record interviews, data confidentiality, and the right to withdraw from the study, were observed. The authors would like to thank the Student Research Committee of Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran, for their support, cooperation, and assistance throughout the study period (code: IR.DUMS.REC.1401.101).

4. Results

Seven participants were involved in the present study, comprising four individuals with a master's degree and three with a doctorate degree. Among them, five were contract employees, and two were committed to service. The participants had an average work experience of 13.1 years, an average marriage duration of 10.4 years, and most had one child. Table 1 presents the demographic information.

| No. | Age | Level of Education | Work Experience | Employment Status | Duration of Marriage | Number of Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | M.A. | 14 | Contract | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | 36 | M.A. | 10 | Contract | 9 | 1 |

| 3 | 42 | M.A. | 18 | Contract | 13 | 1 |

| 4 | 47 | Ph.D. | 15 | Committed to service | 14 | 2 |

| 5 | 41 | M.A. | 13 | Contract | 13 | 3 |

| 6 | 42 | Ph.D. | 7 | Contract | 10 | 1 |

| 7 | 47 | Ph.D. | 15 | Committed to service | 22 | 2 |

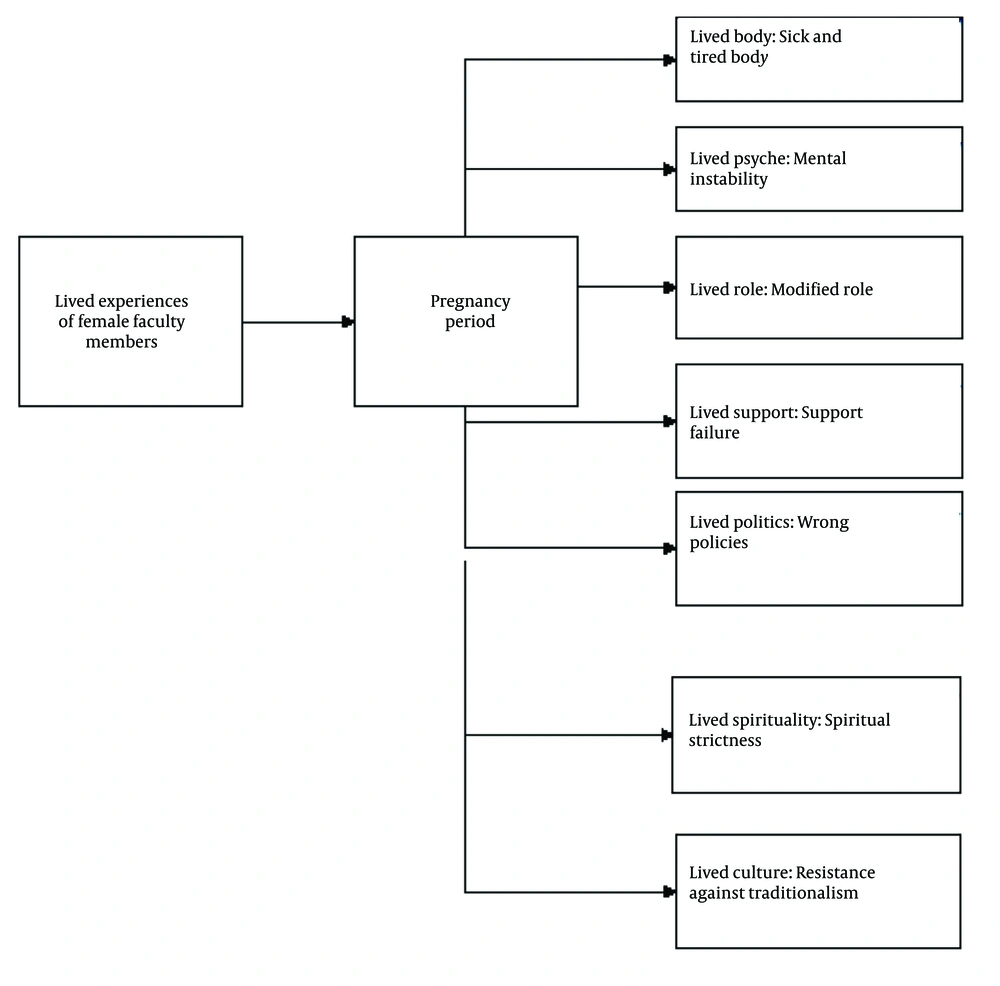

The lived experiences of medical faculty members during pregnancy were categorized into seven subthemes (Figure 1).

4.1. Lived Body: Sick and Tired Body

Most participants reported experiencing health issues such as frequent vomiting, indigestion, heartburn, and, in many cases, headaches, back pain, chest pain, and uterine contractions. Viral diseases also posed a risk to their conditions. Factors such as long working hours, fatigue, insufficient rest, job stress, and lack of attention to ergonomics appeared to contribute to these problems. Some participants experienced conditions such as gestational diabetes and hypothyroidism, with repeated bleeding during pregnancy posing a threat of miscarriage. Hypotension, dizziness, and weakness were also reported by some participants.

Participant 3 stated, "In the first and third trimesters, I had severe chest pain as I slept sitting." Participant 1 shared, "I had a stomach ache one day before my delivery, and I vomited three times in one day."

4.2. Lived Psyche: Mental Instability

Most participants experienced significant anxiety and worry during pregnancy, often related to pregnancy complications and their perceived inability to fulfill roles. In some cases, concerns about threatening pregnancy conditions were exacerbated in participants with pre-existing anxiety disorders and phobias, becoming particularly severe in the third trimester. Some participants reported experiencing depression, isolation, and crying without apparent reason during pregnancy. Although they desired to have children, many expressed regret about their pregnancies. Confronting the negative consequences of pregnancy can lead to maternal regret, exacerbating physical symptoms and potentially predicting postpartum depression.

Participant 5 noted, "Every disturbing news would make me cry, so it was very unnatural." Participant 7 shared, "Most of the time when my husband went out, I didn't go out with him and I wanted to be alone."

4.3. Lived Role: Modified Role

Most participants reported that their maternal role for other children weakened during pregnancy due to pregnancy-related issues, and their spousal role was similarly affected. This often resulted in reduced sexual relations and increased marital conflicts. In the workplace, participants noted a reduction in working hours and a decline in the quality of work performance, frequently citing conflicts between maternal and occupational roles as a source of significant stress and negative perceptions of pregnancy.

Participants suggested that the delineation of duties for women and men in the workplace should be differentiated, particularly for pregnant women. The high workload, coupled with attending practical classes and internships, exacerbates the difficulty of working conditions, increasing the incidence of physical problems such as back pain and exposing individuals to the physical and mental effects of pregnancy.

Participant 1 stated, "I tried to take days off when I had no class or go to work." Participant 3 shared, "During the last months of pregnancy, I was only preparing food to eat, but I had no ability to do more."

4.4. Lived Support: Support Failure

All participants reported insufficient support for pregnant women in the workplace, which exacerbates their concerns. They highlighted a lack of understanding of pregnant women's needs in the workplace, resulting in inadequate financial and welfare facilities for pregnant female faculty members. Many participants noted that while they received support from their husbands and friends, it was insufficient to address the challenges faced by pregnant women. The lack of adequate support can lead to mental health issues and a negative pregnancy experience.

Participant 4 remarked, "They didn't provide me with any facilities; they didn't even reduce my working hours." Participant 6 stated, "We were really in financial trouble because we lost part of our income due to pregnancy."

4.5. Lived Politics: Wrong Policies

Participants expressed that, despite government recommendations to encourage childbearing and maintain a young population, adequate and effective policies have not been implemented to improve family conditions or incentivize young people to have children. They viewed government advice to families as ill-considered and misguided. Due to their higher education, faculty members possess a far-sighted perspective and make decisions based on potential consequences. Without clear instructions to support pregnant women in the workplace, they regard government recommendations for childbearing as ineffective.

Participant 7 noted, "There is no change in regulations for pregnant working women; the same regulations apply to non-pregnant women and even men." Participant 6 questioned, "What instructions does the government have for pregnant women to reduce their problems?"

4.6. Lived Spirituality: Spiritual Strictness

Many participants highlighted the strictness applied during the fasting months for pregnant women, which often leads to physical issues such as weakness in the workplace. Female faculty members felt that, because job rules and guidelines are predominantly established by men, there is a lack of proper understanding of pregnancy conditions, resulting in spiritual hardships during the fasting months.

Participant 4 shared, "Whenever I took a flask to brew tea, they warned me that security would caution you, even though all my colleagues saw me and knew that I could not fast."

4.7. Lived Culture: Resistance Against Traditionalism

Most participants reported that, despite their high level of awareness regarding maternal care during pregnancy, they frequently faced cultural pressures from those around them, who cautioned them with old beliefs. This often led to resistance against these traditional views. To minimize conflicts with outdated beliefs, participants attempted to distance themselves from individuals holding such views. However, this distancing sometimes resulted in a greater sense of loneliness, which they preferred over the stress of confronting traditional beliefs, as it brought them more peace. In less developed societies, traditionalism can marginalize intellectuals.

Participant 5 noted, "My mother-in-law often told me not to go to work to have a bigger child." Participant 6 shared, "My mother used to tell me to eat carrots to make your child's eyes strong, while it was harmful to me."

5. Discussion

The evolving roles and positions of women have increased their presence in various social and public fields, influencing changes in maternal and childbearing actions. Motherhood is inextricably linked with women's roles in the family and society. This qualitative study was conducted to elucidate the experiences of female faculty members regarding pregnancy and delivery. The identified themes included a sick and tired body, mental instability, modified roles, lack of support, incorrect policies, spiritual strictness, and resistance to traditionalism.

The study results indicated that female faculty members primarily expressed their lived experiences of pregnancy and delivery through physical problems and fatigue. Generally, working conditions for women in the workplace vary, leading to different levels of burnout. A study showed that burnout causes numerous complications during the nine months of pregnancy for working women, with premature birth being one of the most significant (22). In a study conducted in Pakistan, Rabia et al. found that most pregnant working women frequently reported issues such as prolonged nausea, cough, low and high blood pressure, dizziness, back pain, anemia, and stomach ache (23). However, another study indicated that housewives typically experience more problems than working mothers, potentially due to higher levels of education and social status (24). These challenges pose serious issues for women in the workplace, which they recount with deep concern (25).

The second theme derived was mental instability. According to the study results, female faculty members experienced significant difficulty and stress in their daily lives due to multiple roles during pregnancy and delivery. Stress, fear, worry, anxiety, depression, and loneliness were prevalent among faculty women during this period. Some field studies have shown that working women experience more anxiety compared to housewives, attributed to their multiple roles. Women who combine occupational roles with marital and family roles are more likely to suffer from depression than men. Additionally, the pressure from multiple roles limits career advancement for women (26), aligning with the present study's findings. However, several previous studies reported that housewives or women who did not work during pregnancy were at higher risk of psychological stress and anxiety compared to those who worked during pregnancy (26, 27). Furthermore, physical and mental problems during pregnancy have synergistic effects (28).

Another theme identified in this study was women's role conflict, characterized by the imbalance and balance between multiple roles. Working women, who juggle maternal, occupational, and educational responsibilities, often encounter conflicts related to work, marriage, pregnancy, motherhood, and role pressure. This creates numerous challenges in their family and work life. Many studies have documented work and family conflict (29, 30). The literature indicates that working women and mothers experience more work-family conflict compared to men. Erdamar and Demirel, in their study "Work-Family Conflict Among Teachers," found that physical and mental fatigue at work complicates taking responsibility at home, and issues arising from work contribute to tension at home (31). Women engaged in activities outside the home face different challenges compared to men, highlighting more pronounced role problems and impacts on marital lifestyle, particularly in developing countries (32).

A study showed that due to workplace and job conditions, working women face role pressure and gender inequality in work and family settings. The maternal role increases costs, such as less time for children, while also offering opportunities for personal and interpersonal development (2). The allocation of educational workload and organizational services in universities significantly influences the quantity and quality of work for academic staff. Educational and stressful positions are often assigned to women, while management roles are given to men, exacerbating work stress due to gender inequality (33, 34). Given the seriousness of this issue, reducing women's occupational conflicts is crucial. Attention must be paid to macro-social policies in addition to individual-based solutions.

Another theme was the lack of support. Pregnancy, being a lengthy process, necessitates long-term support from those around. Previous studies globally have shown that new mothers' experiences are marked by unmet needs, dissatisfaction, and confusion about where to seek help as they quickly adapt to the maternal role (35). A study found that women were dissatisfied with the emotional and mental support received in early pregnancy (36). Workplace experiences have been reported as pleasant for some women and challenging for others (23). According to working mothers, the most important source of emotional and mental support is their husbands, and without them, balancing private and public spheres is difficult. Friendly and informal relationships with colleagues and financial assistance in some jobs can enhance job satisfaction (37). Susanto et al. noted that maternal problems and challenges for working women intensify when family support policies are limited (38).

Despite existing challenges, participants stated that motherhood is very important, viewing having a child as a life necessity. They value the unique emotional and spiritual experience of motherhood, though they do not feel the need for more children (38). According to social support theory, childbearing is deeply rooted in social support, which acts as a protective factor against mental pressure and significantly impacts social functioning (39). Due to insufficient social support for working mothers and the undervaluation of their childbearing, working women do not take a proactive approach to addressing fertility reduction in Iran. They view childbearing as an individual and family decision rather than a social goal. Therefore, population increase policies that do not consider the necessary conditions and facilitate childbearing for all social groups, especially those leading fertility reduction, cannot achieve general population policy goals or promise fertility above the replacement level (40). Finally, job dissatisfaction and family-work conflict pose the greatest risk of psychological distress (41).

Participants highlighted the government's ineffective policies as a significant concern. Past demographic policies have become ingrained in societal customs and culture over the years, making it challenging to change people's attitudes quickly. This shift requires substantial time and specialized, applicable, and accepted planning. Contradictory population policies and inefficient or unenforceable incentive policies foster distrust, leading some members of society to worry about the increased economic burden on their lives (42). Hajian and Maktoobian identified contradictions in population policies, lack of trust in encouraging policies, and the requests of women and population policies as indicators of policy inefficiency. Current population policies remain conflicting and inconsistent, with efforts to encourage population growth clashing with the views of educated and working women who cite inconsistencies between these needs and existing realities (43).

The country's policies to increase childbearing, adopted with a directive approach, lack coherence, purposefulness, and effective encouragement. Couples are hesitant to have children based on these policies, believing that incentive policies cannot meet the family's basic needs. Having more children could exacerbate problems that families may struggle to resolve in the future, leading to increasing institutional distrust and policy non-fulfillment (44). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the conditions, experiences, and mental meanings of working women, listen to their problems and demands, and develop programs and policies that facilitate childbearing without harming the economy (45). Educated women strive to provide a new social identity for women facing misguided policies and have a better understanding of gender inequality (46).

Another concern raised by female faculty members was spiritual strictness. Participants reported that during Ramadan, there is strictness in the workplace for pregnant women, who are expected not to eat during fasting hours out of respect for fasting colleagues. However, some pregnant women need to eat meals at work due to physical limitations. Islam permits fasting only if it does not adversely affect the mother and fetus (47, 48). Spiritual dryness can lead to job burnout, stress, and negative emotions, posing significant risks for pregnant women, even if they are not directly involved (49).

Resistance to traditionalism was a significant theme identified by working women as part of their pregnancy experiences. Some participants reported that family members suggested specific dietary restrictions, and failure to adhere to these suggestions resulted in being labeled as negligent mothers. Food taboos are traditional practices that may restrict or deny access to various nutritious and safe foods, leaving women vulnerable (50). Studies have shown that mothers avoid consuming beans, eggs, fish, meat products, potatoes, fruits, butter, and pumpkin, which are rich in essential micronutrients, protein, and carbohydrates (51-53). Research conducted in Ethiopia also highlighted the experience of food taboos among mothers during pregnancy, with reasons including fear of delivery difficulty, long and painful labor, miscarriage, large fetus, and indigestion (54).

Some studies have indicated that foods such as milk and its products are taboo for pregnant mothers due to beliefs that they may affect the fetus's head and face (55). Additional studies in Debretabor, Amhara, and Shashemene, Oromia, reported that nearly half of the women observed had nutritional taboos (56, 57). Research conducted in West Bengal and Africa also documented varying levels of food taboos among pregnant mothers (50, 58). Ethnic differences and diverse cultures influence different stages of pregnancy and delivery as a biological phenomenon. Understanding beliefs and traditions related to delivery is crucial, as policy-making to improve pregnant mothers' health will remain ineffective without this understanding (59). Therefore, recognizing different ideas, customs, and behavioral restrictions in each culture is essential for providing effective health care.

Faculty members in the present study reported adverse memories of their pregnancy period, which caused significant psychological distress and, according to another study, endangered their mental health (60). The factors mentioned above contribute to mothers' fear of having children, making pregnancy a traumatic experience for them (61).

5.1. Conclusions

The transition to motherhood presents significant challenges for female faculty members. However, a supportive social and political environment, coupled with a friendly and supportive approach towards family, work, and living conditions, as well as emotional support from family, particularly spouses, can facilitate a smoother transition to motherhood. The findings of this study will assist policymakers and program designers in providing more effective support in the future.

To improve the position of female faculty members in society, relevant organizations should implement work-family balance programs. These programs may include providing special welfare facilities, offering numerous training courses to help balance career and family roles, and emphasizing the importance of women's roles in the family. Additionally, passing and promulgating regulations to support female faculty members, such as granting incentive leave and addressing the beliefs and attitudes of senior organizational managers, are crucial steps towards enhancing their societal position.

5.2. Limitations

As this study was qualitative and data collection concluded with data saturation, the number of participants is small, limiting the generalizability of the results to other groups of working women. Additionally, all participants in this study were women who had successful deliveries, so the findings may differ for women with a history of abortion. It is recommended to conduct separate studies for women with a history of abortion, as well as those who have undergone cesarean and vaginal deliveries.

Another limitation of this study is the research environment, which was conducted at a type 3 university. Consequently, the results may not be generalizable to larger and type 1 universities.