1. Background

Relational rumination is defined as the repetitive thoughts that individuals experience about the viability and reliability of their current or past romantic relationships. This form of rumination often involves analyzing interactions, constantly questioning the overall quality of the relationship, or becoming preoccupied with past relational experiences (1). Romantic relationships play a central role in human social and emotional well-being, fundamentally shaping psychological health and personal growth (2). As inherently social beings, humans demonstrate a psychological drive to establish and sustain intimate interpersonal connections (3). The importance of relationships in our lives is eloquently captured by Berscheid (4), who states, "We are born in relationship, we live our lives in relationship with others and as we die, the effects of our relationships live on in the lives of those we leave behind, and reflect in all aspects of their lives" (p. 261 - 262). The quality of romantic relationships shapes mental and physical health, life satisfaction, social functioning, and the well-being of children (5). However, despite the importance of these relationships, many individuals face significant challenges within them, leading to various personal concerns. When romantic relationships encounter problems or become dissatisfying, individuals often experience intense rumination accompanied by negative thoughts and emotions directed toward their relationship (6).

Recent research underscores the significance of rumination as a transdiagnostic cognitive process that plays a critical role in the progress and maintenance of various psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and maladaptive behaviors (7). According to Nolen-Hoeksema’s theory (8), individuals characterized by a ruminative response style tend to exhibit their negative moods by repeatedly and passively focusing on them (9, 10). Building on this understanding, ruminative thoughts can vary greatly in content (11), but we generally divide rumination into two major categories: Intrapersonal and interpersonal rumination. Intrapersonal rumination tends to focus on internal and self-related issues (12). In contrast, interpersonal rumination focuses on external issues and is a process in which two people passively and repeatedly discuss and talk to each other about problems and symptoms, and ask unanswered questions (13).

Given the significant impact of rumination on mental health, exploring its different forms provides valuable insights into coping mechanisms and the perpetuation of emotional distress (12). In this regard, researchers have specifically highlighted relational rumination as a distinct form of interpersonal rumination worthy of further investigation (14, 15). Studies have shown that individuals who are engaged in continuous rumination are likely to have difficulty in maintaining intimate relationships (16), and higher levels of rumination have been associated with more cautious or contradictory views of such relationships (14). This connection emphasizes the circular nature of relational rumination, where negative thoughts about the relationship may contribute to ongoing relationship difficulties, subsequently intensifying ruminative patterns. The self-regulation perspective suggests that relational rumination occurs when one of the goals of the relationship is blocked; these types of goals often receive attention from individuals because they are related to more abstract purposes (6). When these goals are blocked, individuals become vulnerable to rumination about an unattainable relationship goal, while also experiencing strong negative effects such as anger and anxiety, which mutually reinforce each other (12). In previous studies, a significant relationship has been observed between relational rumination and negative emotions (12, 17, 18). Therefore, addressing relational rumination is essential for mitigating its adverse emotional consequences and improving relational functioning.

In the context of Iranian society, these issues take on unique dimensions due to specific cultural and religious values. While romantic relationships between young men and women have a long history, they often face unique challenges in Iran. Many of these relationships are formed secretly and without the knowledge or consent of families, leading to greater personal and social risks compared to other cultural contexts (19). In recent years, the increasing use of the internet and social media, the expansion of university settings, and shifting societal values have contributed to a significant rise in the prevalence of romantic relationships among Iranian youth, as well as more positive attitudes toward such relationships (20-22). Consequently, relational rumination may be particularly pronounced in this cultural context, where societal pressures intensify relationship challenges and the resulting emotional distress.

Despite the apparent importance of relational rumination, there was previously no comprehensive questionnaire available to measure this construct in the Iranian population. Previous scales for relational rumination were either too specific (15) or lacked robust evaluation of their validity and reliability (6, 23). To formulate and validate a short-term, multidimensional, and self-report scale to measure romantic relationship-related rumination, Senkans et al. (1) created a 16-item Relational Rumination Questionnaire (RelRQ) with three factors, including relationship uncertainty rumination (RU), romantic preoccupation rumination (RP), and break-up rumination (BU). The total score of the scale and subscales indicated acceptable internal consistency and good test-retest reliability. The factor structure indicated themes such as rumination about the start of a relationship, stable relationships, and previous partners and separations (1).

2. Objectives

Given that the psychometric properties of the RelRQ have not been explored in non-English-speaking populations, particularly within culturally diverse contexts like Iran, the present study aims to address this gap by examining the psychometric properties, factor structure, and measurement invariance of the RelRQ within a Farsi-speaking population. We specifically hypothesize that the Persian version of the RelRQ will retain the original three-factor structure and demonstrate acceptable internal consistency. Furthermore, we expect it to show criterion validity through positive correlations with measures of depression, trait rumination, and co-rumination.

3. Methods

3.1. Translation Procedure

The Persian version of the RelRQ was developed following established international guidelines for the cross-cultural adaptation of self-administered scales (24). The process involved forward translation by a clinical psychologist and psychiatrist. To ensure accuracy and equivalence, back-translation was conducted by an independent English language specialist. An expert panel reviewed the semantic, idiomatic, and conceptual equivalence of the translations. Based on the cross-cultural research protocol, the Persian version of the RelRQ was administered to 20 initial participants. These individuals completed the questionnaire and reported any formal issues, including difficulty in understanding or ambiguity of items. Based on their feedback, we finalized the questionnaire. This comprehensive approach ensured the cultural and linguistic appropriateness of the Persian RelRQ for use in research and clinical settings.

3.2. Procedure

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZUMS.REC.1402.153). This was a cross-sectional study. The population of this study included all individuals aged 18 to 50 years residing in Zanjan, Iran. Sampling was conducted using a convenience method from August 2023 to November 2023 through online announcements, including a brief description of the aim and method of this study along with a link to participate in the research, on Zanjan social networks. Before completing the questionnaire, online informed consent was obtained from the participants. Invalid responses were defined as fixed responses (choosing one answer for multiple questions or selecting the minimum/maximum score for all questions on a scale) or contradictory answers (e.g., giving the lowest score on one scale with very high scores on another scale).

3.3. Recruitment and Participants

The sample size was estimated using the Bentler and Chou rule (25), which recommends 5 to 20 participants per item. In this study, in accordance with this rule and previous studies, 40 participants per item were used (26). A total of 665 questionnaires were collected, and after removing invalid data, 604 valid responses remained. The participants in this study were 604 individuals from the general population. The demographic features are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Men (n = 188) | Women (n = 476) | χ2 or t (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2.99 b (0.393) | ||

| 18 - 25 | 126 (67.0) | 342 (71.8) | |

| 26 - 30 | 23 (12.2) | 60 (12.6) | |

| 31 - 40 | 22 (11.7) | 46 (9.7) | |

| 41 - 50 | 17 (9.0) | 28 (5.9) | |

| Marital status | 0.472 b (0.492) | ||

| Single | 156 (83.0) | 384 (80.7) | |

| Married | 32 (17.0) | 92 (19.3) | |

| Relationship status | 3.08 b (0.380) | ||

| In relationship | 68 (36.2) | 190 (39.9) | |

| Unrequited love | 16 (8.5) | 27 (5.7) | |

| Romantic heartbreak | 11 (5.9) | 37 (7.8) | |

| No relationship | 93 (49.5) | 222 (46.6) | |

| Educational attainment | 12.84 b (0.025) | ||

| Undergraduate | 116 (61.6) | 338 (71.0) | |

| Postgraduate | 72 (38.4) | 138 (29.0) | |

| RelRQ | 30.53 ± 12.85 | 30.03 ± 11.32 | 0.499 c (0.618) |

| RU | 10.65 ± 5.19 | 10.78 ± 4.90 | -0.311 c (0.756) |

| RP | 13.28 ± 6.58 | 12.80 ± 6.00 | 0.893 c (0.372) |

| BU | 6.61 ± 3.53 | 6.44 ± 3.35 | 0.558 c (0.577) |

The Results of Sociodemographic and Relational Rumination Questionnaires by Gender a

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Relational Rumination Questionnaire

Ruminating on romantic relationships is typically linked to interpersonal problems, such as violence against intimate partners and stalking of former romantic partners. Through factor analysis studies, a three-factor structure was confirmed and ultimately revised into a 16-item version, with each item consisting of a 5-point scale (never, rarely, somewhat, often, always). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the items of each of the RelRQ (total score) (0.91), RU (0.92), RP (0.90), and BU (0.91) were calculated and indicated good internal consistency (1).

3.4.2. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition

The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire developed by Beck et al. in 2011 (27) to assess the presence and severity of depression symptoms based on experiences over the previous 2 weeks. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from "0" to "3." The total score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. The BDI-II manual categorizes scores as minimal (0 - 13), mild (14 - 19), moderate (20 - 28), and severe (29 - 63) depression. The questionnaire has high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.89 to 0.94 in both clinical and non-clinical samples. Test-retest reliability has also been established, with coefficients ranging from 0.73 to 0.96 (28). Moreover, its construct validity has been confirmed through factor analysis in various studies (29). In Iran, Ghassemzadeh et al. conducted a validity and reliability study of this questionnaire, reporting satisfactory psychometric properties with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (30).

3.4.3. Ruminative Response Scale-Short Form

The Ruminative Response Scale-Short Form (RRS-SF) is a 10-item self-report instrument developed by Treynor in 2003 (31) to measure individuals’ tendency to ruminate in response to feelings of sadness and depression. It uses a 4-point Likert scale and contains two subscales called brooding and reflection. The total score ranges from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher degrees of ruminative symptoms. The RRS indicated high alpha ranges from 0.74 to 0.83, and its construct validity has been confirmed through factor analysis (32). The RRS-SF demonstrated convergent validity through significant positive correlations with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (33). The Persian version of the questionnaire demonstrated high validity and reliability, with an alpha coefficient of 0.90 (34, 35).

3.4.4. Co-Rumination Questionnaire

The Co-Rumination Questionnaire (CRQ) was developed by Rose (36) to measure the degree to which young individuals engage in co-rumination with their same-sex friends. The CRQ consists of 27 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Previous studies have reported high internal consistency (0.90 to 0.97) for the CRQ total scores (37, 38). The Persian version of the questionnaire demonstrated high validity and reliability, with an alpha coefficient of 0.90 (39).

3.5. Data Analysis Method

The first step in the analysis was to conduct a descriptive analysis of the data to understand the distribution of demographic variables and relational rumination in participants. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) method to evaluate the three-factor model of the RelRQ. Mardia’s coefficients of multivariate skewness were employed to evaluate the multivariate normality of all models, revealing that the data exhibited normality. Model fit was assessed using various indices: Chi-square fit statistics (CMIN/DF), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, 90% CI). Acceptable fit was defined as CMIN/DF ≤ 3, TLI and CFI ≥ 0.900, and RMSEA ≤ 0.05 (40).

Measurement invariance was assessed to determine whether the RelRQ exhibits equivalent psychometric properties across genders. This analysis ensures that the construct of relational rumination is measured consistently across genders, allowing for valid comparisons. Invariance was tested using a series of increasingly constrained models (configural, metric, scalar). Model fit was compared using changes in CFI (ΔCFI) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) between the less restrictive and more restrictive models. Acceptable invariance was defined as ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 and ΔCFI ≤ 0.01 (41).

Internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Criterion validity was evaluated by examining correlations with established measures. Analyses were performed using Amos version 24 and SPSS version 27.

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants were not married (83.0% of men; 80.7% of women). In terms of relationship status, 36.2% of men and 39.9% of women were in a relationship. The mean score for relational rumination was 30.53 for men and 30.03 for women. According to the t-test, the difference between genders was not statistically significant (t = 0.499, P = 0.618).

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Relational Rumination Questionnaire Items

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis) and Cronbach’s alpha for the items. As shown in Table 2, the distribution of samples based on the skewness and kurtosis of the items did not exceed the standard range of ± 2, except for item No. 14. The corrected within-item correlation shows a moderate and significant relationship between the items and the total score. The internal consistency coefficients based on Cronbach’s alpha did not exceed 0.91 by removing any of the items. The participants responded to all questionnaire items nearly consistently, and the dispersion level was low.

| Items | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Corrected Item-Total R | Cronbach’s Alpha If Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.54 ± 1.21 | 0.36 | -0.75 | 0.56 | 0.905 |

| 2 | 2.05 ± 1.16 | 0.87 | -0.18 | 0.61 | 0.904 |

| 3 | 2.09 ± 1.21 | 0.84 | -0.36 | 0.55 | 0.906 |

| 4 | 1.75 ± 1.07 | 1.35 | 0.93 | 0.57 | 0.905 |

| 5 | 2.03 ± 1.19 | 0.92 | -0.17 | 0.58 | 0.904 |

| 6 | 1.88 ± 1.14 | 1.16 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.904 |

| 7 | 2.18 ± 1.35 | 0.83 | -0.57 | 0.64 | 0.902 |

| 8 | 1.62 ± 0.94 | 1.53 | 1.75 | 0.54 | 0.906 |

| 9 | 1.63 ± 1.09 | 1.74 | 2.11 | 0.59 | 0.904 |

| 10 | 2.04 ± 1.27 | 1.00 | -0.14 | 0.65 | 0.902 |

| 11 | 1.51 ± 0.90 | 1.89 | 3.16 | 0.52 | 0.906 |

| 12 | 1.97 ± 1.21 | 1.06 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.902 |

| 13 | 1.72 ± 1.05 | 1.48 | 1.45 | 0.64 | 0.903 |

| 14 | 1.43 ± 0.90 | 2.39 | 5.47 | 0.50 | 0.907 |

| 15 | 1.52 ± 0.92 | 1.95 | 3.38 | 0.55 | 0.906 |

| 16 | 2.13 ± 1.28 | 0.85 | -0.40 | 0.65 | 0.902 |

Item-Level Statistics for the Non-finalize Relational Rumination Questionnaire

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

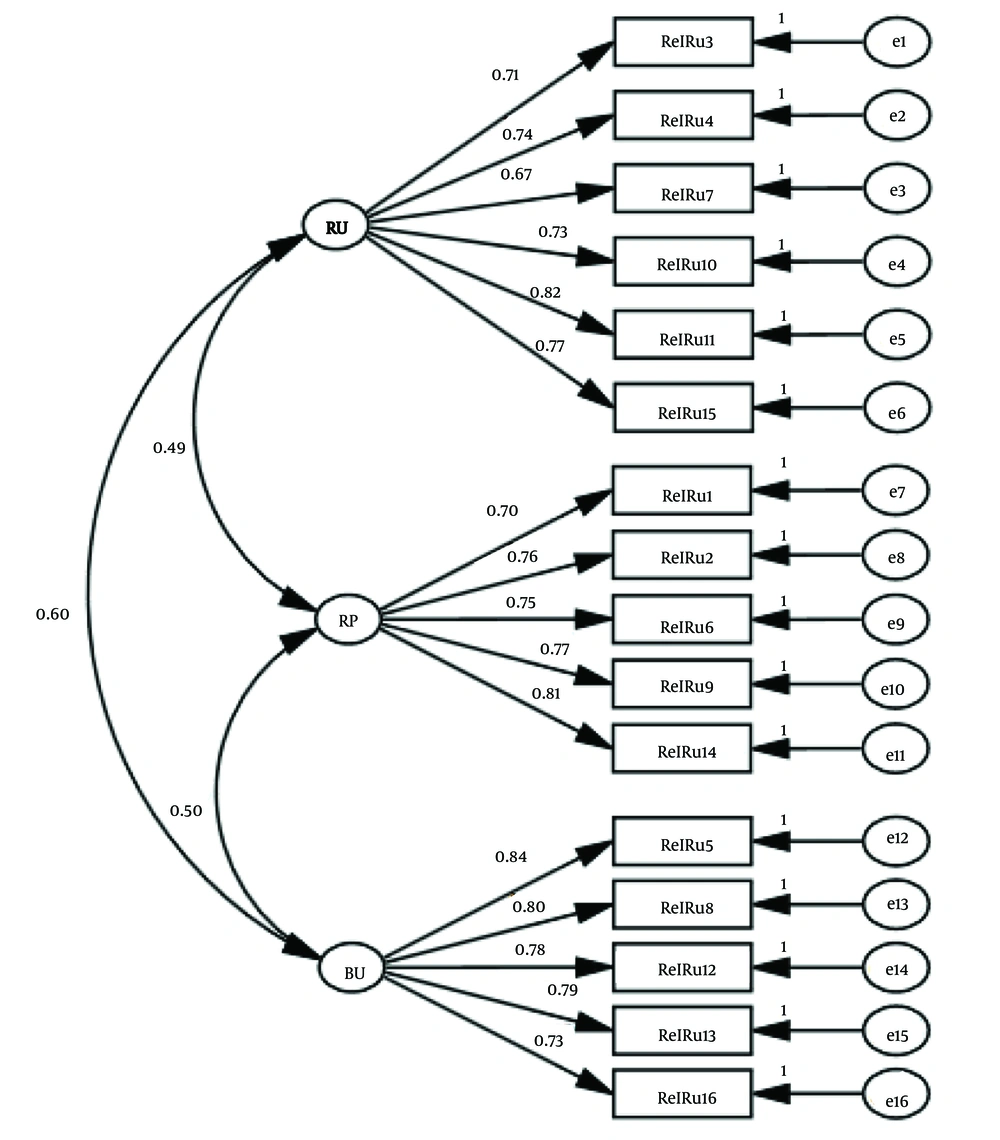

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using Amos version 24 to validate the three-factor structure identified by a previous study. As shown in Table 3, the final model exhibits a three-factor structure, with path coefficients for each item and its underlying factor ranging from 0.68 to 0.83. This indicates that each item has an acceptable predictive weight with the main factor. As shown in Figure 1, the relationships between factor path coefficients range from 0.49 to 0.60, indicating that each factor exists independently of the other factors. Based on modification indices, when it was statistically and theoretically possible, the covariance errors between items were freed for each of the three factors. The fit indices of the 16-item model have the following specifications: χ2 = 234.604, df = 89, GFI = 0.959, CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.049, as shown in Table 4.

| Items | Factor Loading | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Factor 1: RU | |||

| (11) Nagging doubts about my partner’s faithfulness pop up in my mind. | 0.829 | - | - |

| (15) I imagine my partner cheating on me even though I don’t want to. | 0.773 | - | - |

| (4) Thoughts about my partner cheating on me stress me out. | 0.747 | - | - |

| (10) I get caught up in imagining scenarios in which my partner would cheat on me. | 0.740 | - | - |

| (3) The thought of my partner sleeping with somebody else crosses my mind. | 0.712 | - | - |

| (7) I keep thinking that other people are interested in my partner. | 0.676 | - | - |

| Factor 2:RP | |||

| (14) I think about how to find a romantic relationship to avoid ending up alone. | - | 0.813 | - |

| (9) Thoughts about why I am not in a relationship pop into my head without me wanting them to. | - | 0.771 | - |

| (2) Thoughts about how to find a partner plague my mind. | - | 0.769 | - |

| (6) I keep on wondering why my friends have romantic relationships and I don’t. | - | 0.756 | - |

| (1) I think of strategies to get into a romantic relationship over and over again. | - | 0.700 | - |

| Factor 3:BU | |||

| (5) I go over and over the reasons why my relationship(s) with my ex-partner(s) ended. | - | - | 0.842 |

| (8) I think about how I should have prevented the break-up with an ex-partner. | - | - | 0.806 |

| (13) Thoughts about my ex-partner(s) distract me from other things I should be doing. | - | - | 0.798 |

| (12) I think over and over again about how to re-establish the relationship with my ex-partner. | - | - | 0.784 |

| (16) I wish I could stop thinking about my ex-partner(s), but I can’t. | - | - | 0.738 |

The Factor Structure of the Relational Rumination Questionnaire-16 in a Sample of 605 People

| Model | χ2 | df/P | GFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor structure invariance | ||||||

| Model 1. 16-item RelRQ | 234.604 | df = 89 | 0.959 | 0.976 | 0.968 | 0.049 |

| Measurement invariance | ||||||

| Configural invariance | 353.91 (178) a | P = 0.000 | - | 0.972 | 0.962 | 0.039 (0.033; 0.045) b |

| Metric invariance | 373.90 (191) a | P = 0.000 | - | 0.971 | 0.963 | 0.038 (0.032; 0.044) b |

| Scalar invariance | 386.45 (197) a | P = 0.000 | - | 0.970 | 0.963 | 0.038 (0.032; 0.044) b |

Fit Statistics for the Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model (N = 605)

4.4. Measurement Invariance

Table 4 presents the results of the measurement invariance testing for the three-factor model. The model displayed satisfactory fit indices for both males and females, as indicated by the TLI, CFI, and RMSEA. Additionally, the configural, metric, and scalar invariance models tested between gender groups showed satisfactory fit indices based on the TLI, CFI, and RMSEA. There were no indications of degradation in model fit when comparing the configural invariance models (Δχ2 = 19.99; P = .000; ΔCFI = -0.001; ΔTLI = -0.001; ΔRMSEA = 0.001), as well as between the metric and scalar invariance models (Δχ2 = 12.55; P = .000; ΔCFI = 0.001; ΔTLI = 0.000; ΔRMSEA = 0.000). Consequently, in accordance with Chen’s recommendations (42), invariance was established for the three-factor model across both genders.

4.5. Criterion Validity

To evaluate the criterion validity of the 16-item RelRQ, correlations were estimated between the total score and subscales of the RelRQ with other measures of rumination, as well as the total score of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) as another indicator related to rumination. The results of these correlations are displayed in the correlation matrix (Table 5). The results indicate that the total score of the RelRQ has the highest correlation with its underlying subscales. Additionally, the total score and subscales of the RelRQ have significant but weak to moderate correlations with co-rumination and trait rumination. The correlation coefficients between the total scores of RelRQ measures and depression range from 0.25 to 0.40 and are significant in all cases.

Correlation Matrix of Relational Rumination Questionnaire with Beck Depressive Inventory-II, Rumination Response Scale, and Co-Rumination Questionnaire

5. Discussion

The present study focused on examining the factor structure, measurement invariance, and psychometric properties of the Persian version of the RelRQ within the Iranian cultural framework. It is important to note that the cultural context in Iran strongly affects romantic relationships and relational rumination. Due to the traditional nature of Iranian society, romantic relationships often face significant societal pressures, leading to covert interactions and heightened emotional strain. Consequently, relational rumination in Iran may have a more pronounced psychological impact, potentially contributing to heightened levels of anxiety and depression.

The findings demonstrate that the three factors of the Persian version of the 16-item RelRQ — RU rumination, RP rumination, and break-up rumination — have acceptable internal consistency (with an alpha coefficient of 0.91), criterion validity, and measurement invariance across gender, similar to the original version (1). As this was the first study to examine the validity and reliability of the RelRQ, direct comparisons with other cultures are limited. However, the factor structure and coefficients align closely with the original English version.

Additionally, this study represents a pioneering effort to assess the measurement invariance of the RelRQ. The findings demonstrate that the scale exhibits negligible bias across respondents, with ΔCFI = 0.001 and ΔRMSEA = 0.001. This aligns with the perspective of Putnick and Bornstein (43), who advocate for the utilization of scalar measurement invariance analyses as comprehensive evaluations of construct functioning across diverse groups, transcending their role as mere preliminary tests. These results augment the growing body of research on the RelRQ’s psychometric integrity and highlight its generalizability across genders.

Furthermore, the present study shows that the Persian version of the RelRQ has a positive and significant correlation with other psychological constructs. The examination of this questionnaire’s criterion validity and correlation results revealed a significant and positive correlation between the RelRQ and the BDI-II (r = 0.40). Additionally, a positive and significant correlation emerged between this questionnaire and other forms of rumination, such as trait rumination (r = 0.37) and co-rumination (r = 0.18), aligning with prior research in this field and affirming the questionnaire’s criterion validity.

The findings of this study have important clinical implications. Relational rumination can exacerbate symptoms of depression and anxiety, hinder recovery, and negatively impact treatment outcomes (44). Having a reliable and valid tool like the Persian RelRQ enables clinicians to systematically identify individuals who are prone to maladaptive relational rumination. For instance, Starr and Davila (45) highlighted that targeting rumination in therapeutic settings can lead to significant improvements in depressive symptoms and interpersonal relationships. Similarly, Watkins emphasized the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral techniques in reducing rumination by promoting more adaptive thinking patterns (46).

By incorporating the RelRQ into clinical assessments, practitioners can tailor these interventions to focus specifically on relationship-related thoughts. For example, clients scoring high on break-up rumination may benefit from strategies that address grief and loss, while those high on romantic preoccupation rumination may need assistance in managing obsessive thoughts about their partner.

While this study has notable strengths, including a large sample size for assessing the psychometric properties of the RelRQ, several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the findings. The sample had a disproportionate number of female participants; however, adjustments for age and occupation were made to address this imbalance. Future studies can also investigate the divergent and convergent validity with a wide range of criteria such as attachment styles, interpersonal functioning, and other mental health disorders. Longitudinal studies could examine how relational rumination, as measured by the RelRQ, predicts mental health outcomes over time. It is also suggested that the psychometric features of this instrument be examined in other languages and cultural contexts to further establish its universal applicability.

5.1. Conclusions

In summary, the Persian version of the RelRQ demonstrated good reliability and validity and can be used as an effective and extensive research instrument for assessing relational rumination. The Iranian version of the RelRQ demonstrates valid and reliable measurement of various features of rumination about relationships in non-English-speaking cultures. The RelRQ holds considerable promise for advancing scientific understanding of the complex interplay and multifaceted consequences of romantic relationship rumination on overall well-being and psychological functioning.