1. Background

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a type of anxiety disorder characterized by a persistent fear of social situations, leading to avoidance, especially when performing functions or being among unfamiliar people (1). This disorder is one of the most common and debilitating anxiety disorders, with an annual prevalence of approximately 7% and a lifetime prevalence of 13% (2, 3). The prevalence of social anxiety among students ranges from 24% (severe) to 56.6% (moderate severity of symptoms) (4), and other research reports it from 7.8% to 80% on average (5, 6).

The cognitive-behavioral approach, particularly the Clark and Wells model, emphasizes the role of inconsistent beliefs and information-processing biases in the development and maintenance of this disorder. Clark and Wells (1995) highlight the detrimental effect of negative beliefs, such as distorted self-views and high-cost anticipation of negative social events, among socially anxious individuals. Cognitive models also emphasize the role of biases in information processing (e.g., biases in attention, memory, and interpretation of ambiguous stimuli), protective behaviors, avoidance, and post-event processing in the persistence of social anxiety symptoms (7-9).

According to the interpersonal approach, social anxiety is both created and maintained by feelings of social role insecurity, leading individuals to develop various "self-protection" strategies (10). Despite extensive research on the relationship between social anxiety and maladaptive cognitive processing (8, 11), some theoretical models suggest the existence of basic cognitive-emotional structures based on shame in individuals with social anxiety, forming the foundation of negative self-referential cognitions and social anxiety symptoms (12).

In the emotion-focused therapy (EFT) approach, social anxiety is conceptualized as traumatic memories based on shame (13-16), leading to the internalization of cognitive-emotional plans based on shame, which form the core of this disorder (17, 18). In Elliott and Shahar's (2017) emotion-focused theoretical model, primary sources of social anxiety include social degradation experienced in early childhood and adolescence, such as public humiliation, bullying, and various forms of abuse (14). Social humiliation, along with a lack of emotional support, validation, and family warmth, causes traumatic emotional pain (fear, sadness, and shame), directly leading to the creation of emotional schemes based on shame and feelings of inferiority (14).

This shame-based emotional scheme leads to the development of a harsh internal critic, whose role is to prevent further degradation and incomplete appearance (14). According to EFT theory, self-criticism develops as a coping mechanism against feelings of shame, serving to prevent the recurrence of humiliation and further shame. In a study by Shahar et al. on a non-clinical population, shame was shown to mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment experiences (childhood trauma) and social anxiety symptoms (19). Additionally, individuals with high social anxiety experience high levels of shame and self-criticism, with shame mediating the relationship between self-criticism and social anxiety (20).

2. Objectives

Although studies have demonstrated the role of traumatic childhood experiences within the family in contributing to social anxiety, the mechanism of this effect, as well as the impact of early life experiences that exist in a person's memory but are not necessarily traumatic, have not been thoroughly investigated. Additionally, in the two dominant approaches to the treatment of social anxiety, the sustaining and maintaining factors in the psychopathology of social anxiety are primarily addressed, while the role of primary emotions is often neglected.

The constructs of this model were selected based on the theoretical model of Elliott and Shahar, which was proposed for the pathology of social anxiety. Based on this framework, the primary hypothesis of this research was to investigate the effect of memories of early negative childhood experiences, with the mediation of the schema of deficiency/shame and self-criticism, on social anxiety.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

A descriptive correlational method was used for this research. The study population consisted of all students enrolled in public universities affiliated with the Ministry of Science in Tehran for the 2022 - 2023 academic year. The sample selection was based on the availability of Shahid Beheshti University students enrolled from the first semester (February 2022 to July 2023). In general, when using structural equation modeling, it is recommended to have at least 20 samples for each latent variable (21). Strong modeling of structural equations requires a sample size of more than 200 (22). The minimum required sample size of 381 subjects was determined using the Cochran formula. A total of 420 participants successfully completed the research instruments in this study, and their results were statistically evaluated.

Data collection methods included a traditional pen-and-paper questionnaire and an online survey accessible through a specific website, https://porseshnameonline.com, which was distributed to participants via Telegram groups, WhatsApp, and Instagram settings. Additionally, student assistants who cooperated with the counseling center of Shahid Beheshti University provided links to students in faculty groups. The questions were designed on this website in such a way that participants could not proceed to the next question without completing the current one, ensuring that all questions were fully answered. The participants' responses were accessible in an Excel file.

In this study, participants were granted full autonomy to engage in the research process. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the designed questionnaires, where participants ticked the "I agree" option before entering the questions. All participants were assured that the information obtained would be used solely for research purposes and that confidentiality would be respected.

3.2. Research Instruments

3.2.1. Social Phobia Inventory

Connor et al. developed the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), a 17-item scale with subscales for fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms (23). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4. The test-retest reliability of SPIN was adequate (0.78 to 0.89). Cronbach's alpha was 0.94, indicating good internal consistency. The reliability and validity of this scale are well-established in Iran, as reported in several studies (24, 25).

3.2.2. Early Life Experiences Scale

Developed by Gilbert et al., this scale measures memories of personal feelings in the family, related to recalling feelings of being devalued, threatened (feared), and forced to behave in submissive ways. Unlike other scales that ask about parental treatment or specific experiences, this scale focuses on memories of personal emotions in childhood. It consists of 15 items based on a Likert scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = very true) (26). Questions 6, 7, and 9 should be scored in reverse. This scale has three components: Unvalued (3 items), submissiveness (6 items), and threatened (6 items). Gilbert et al. reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.89 for the threatened subscale, 0.85 for the submissiveness subscale, 0.71 for the unvalued subscale, and 0.91 for the total score (26). In a study on Spanish students, internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 for the threat subscale, 0.86 for dominance, 0.81 for worthlessness, and one-month test-retest reliability results were r = 0.90 (27). In Iran, this scale was translated and standardized by Khanjani et al., with internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of 0.74 for the entire scale, 0.85 for submissiveness, 0.66 for feelings of invalidity/worthlessness, 0.80 for feelings of threat, and test-retest correlation coefficients ranging from 0.85 to 0.95 for the subscales (28).

3.2.3. Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form

Developed by Young, the Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form (YSQ-SF) assesses early maladaptive schemas (29). It employs a six-point Likert scale for scoring the 75 items, ranging from one "Completely untrue for me" to six "Describes me perfectly". Higher scores indicate the presence of more maladaptive core beliefs and schemas (30). The internal consistency of the scale is satisfactory, with values typically exceeding 0.80 for the 15 early maladaptive schemas/factors. This study focused solely on the defectiveness/shame subscale (questions 21, 22, 23, 24, 25). Khosravani et al. developed the Persian version of this scale, reporting acceptable levels of reliability and validity (30).

3.2.4. Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale

Developed by Gilbert, Clark, Hempel, Miles, and Eisener in 2004, this scale consists of 22 items across three dimensions: Inadequate self, hated self, and reassure self (31, 32). These dimensions assess feelings of inferiority, self-punishment, and self-reassurance, respectively (31). Responses are given on a 5-point Likert scale, with high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of 0.90 for self-inadequacy and 0.86 for self-hatred and self-reassurance). The Iranian version of this scale was translated by Ghahramani et al. and standardized on students, with the SCRS factors' Cronbach's alpha coefficients falling within the desired range (self-hatred, 0.73; self-reassurance, 0.75; self-inadequacy, 0.89) (33).

3.3. Data Analysis

SPSS version 24 was used to analyze descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation, and to calculate Pearson correlation coefficients between variables. SmartPLS-SEM version 3.3.7 was employed for structural partial least squares regression. The mediating roles of shame and self-criticism were assessed using bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) with 5,000 samples. Model validation involved the PROCESS macro and partial least squares regression, with key metrics including R2 values, path coefficients, and the Sobel test for mediation.

4. Results

The data from Table 1 revealed that the research sample consisted of 41.7% male and 58.3% female participants. In terms of marital status, 71% of participants were single, 28% were married, and 7% were divorced. Educational attainment showed that 49% held a bachelor's degree, 36% had a master's degree, and 15% had obtained a doctorate. The average age of the participants was 26.4 years, with a standard deviation of 6.01 years. The age range was from 18 to 47 years.

| Variables | Total No. (%) | SAD | SS | SC | ELE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P- value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | ||

| Genders | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.90 | |||||

| Male | 175 (41.7) | 26.0 ± 15.5 | 13.0 ± 6.3 | 36.7 ± 19.4 | 34.5 ± 11.9 | ||||

| Female | 245 (58.3) | 26.1 ± 3.3 | 13.3 ± 6.6 | 35.4 ± 5.7 | 34.6 ± 11.3 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.92 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.82 | |||||

| Single | 299 (71.2) | 26.2 ± 15.6 | 13.1 ± 6.5 | 36.0 ± 20.1 | 34.3 ± 11.2 | ||||

| Married | 114 (27.1) | 25.8 ± 15.3 | 13.2 ± 6.6 | 36.4 ± 20.2 | 35.11 ± 12.6 | ||||

| Divorced | 7 (1.7) | 28.1 ± 20.3 | 11.8 ± 3.3 | 27.4 ± 11.09 | 33.4 ± 4.9 | ||||

| Education | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.50 | |||||

| BSc | 207 (49.3) | 27.7 ± 16.01) | 13.7 ± 6.1 | 36. 6 ± 19.2 | 34.5 ± 11.2 | ||||

| MSc | 150 (35.7) | 24.01 ± 15.1 | 12.1 ± 6.8 | 33.9 ± 20.4 | 33.9 ± 23.3 | ||||

| Ph.D. | 63 (15) | 26.2 ± 14.9 | 13.6 ± 6.5 | 38.9 ± 20.1 | 36.01 ± 12.4 | ||||

Abbreviations: SAD, social anxiety disorder; SS, shame schema; SC, self-criticism; ELE, early life experiences.

Gender did not show a significant difference in social anxiety levels, as indicated by the t-test result (t (418) = 1.9; P > 0.05). Furthermore, the one-way analysis of variance test demonstrated that there was no significant difference in social anxiety levels across the three educational levels (F (2, 417) = 2.43; P > 0.05). Similarly, there was no variation in social anxiety based on marital status among the three groups (F (2, 417) = 0.08; P > 0.05).

According to the Pearson correlation coefficient results in Table 2, self-criticism (r = 0.64, P < 0.01), the shame/deficiency schema (r = 0.62, P < 0.01), and early life experiences (r = 0.48, P < 0.01) are positively and significantly correlated with social anxiety.

Abbreviations: SAD, social anxiety disorder.

a P < 0.01.

The goodness-of-fit criteria (e.g., SRMR < 0.08, NFI = 0.90) demonstrated that the model was well-suited for the data (Table 3).

| Index (Acceptable Value) | The Obtained Value |

|---|---|

| Average extracted variance (AVE > 0.50) | 0.79 - 0.85 |

| Composite Reliability Index (CR > 0.70) | 0.91 - 0.96 |

| VIF < 5 or VIF between 5 and 10 | 1.96 - 10.3 |

| SRMR < 0.08 | 0.07 |

| NFI > 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Aston-Geisser Q² Index (between 0.15 and 0.35: Strong) | > 0.30 |

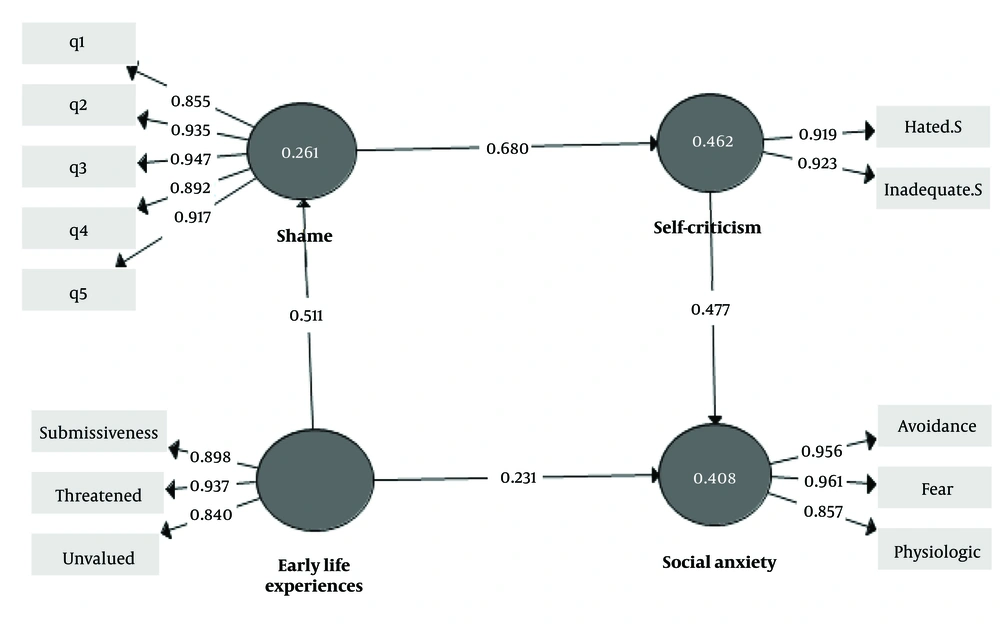

According to the SPSS macro PROCESS, the entire model was statistically significant and explained about 48% of the variance in social anxiety (R² = 0.48; F (4, 415) = 100.3, P < 0.001). Bootstrapping (n = 5,000) was used to construct 95% bias-corrected, accelerated (BCa) CIs for each effect; significant mediation (P < 0.05) was established if CIs did not contain zero. Figure 1 illustrates the sequential mediation model, showing the direct and indirect effects of early life experiences on social anxiety through shame and self-criticism. The coefficients demonstrate the strength and direction of these relationships.

Based on the Partial Least Squares findings with SmartPLS version 3, early life experiences exhibit significant positive correlations with the shame schema (R² = 0.26, β = 0.51, t = 12.4, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.42, 0.58]). Furthermore, within the sequential model's progression, it was observed that shame demonstrates a significant and positive relationship with self-criticism (R² = 0.46, β = 0.67, t = 16.7, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.59, 0.75]). Additionally, self-criticism emerged as a significant predictor of social anxiety (R² = 0.40, β = 0.47, t = 8.2, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.36, 0.58]).

The specific indirect path of early life experiences → shame → self-criticism → social anxiety (β = 0.16, t = 5.36, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.23]) along with the notable direct effects of early life experiences on social anxiety (β = 0.23, t = 4.94, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.32, 0.42]) were also established. Moreover, the total effects (both direct and indirect) of early life experiences on social anxiety were statistically significant (β = 0.39, t = 10.3, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.42, 0.54]).

The results of Figure 1 are presented in more detail in Table 4. These results indicate that early life experiences play a role in the formation of shame as a primary maladaptive emotion or an early emotional process. Self-criticism also forms as a coping mechanism in response to this basic shame to prevent individuals from being shamed again. Finally, this self-criticism in social situations can predict social anxiety symptoms.

| Variables | Path Coefficients (P-Value) | To SC | Indirect Effects (Bias Corrected) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To SAD | To SS | Estimate | Bootstrap 95% Confidence Interval | |||

| Effects from ELE to SAD | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ELE (direct) | 0.23 (0.002) | 0.51 (0.001) | - | - | - | - |

| SS | - | - | 0.68 (0.001) | - | - | - |

| SC | 0.47 (0.001) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total effects (direct and indirect) | 0.39 (0.001) | - | - | - | - | - |

| ELE → SS → SC → SAD | - | - | - | 0.16 (0.001) | 0.32 | 0.42 |

Abbreviations: ELE, early life experiences; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SS, shame schema; SC, self-criticism.

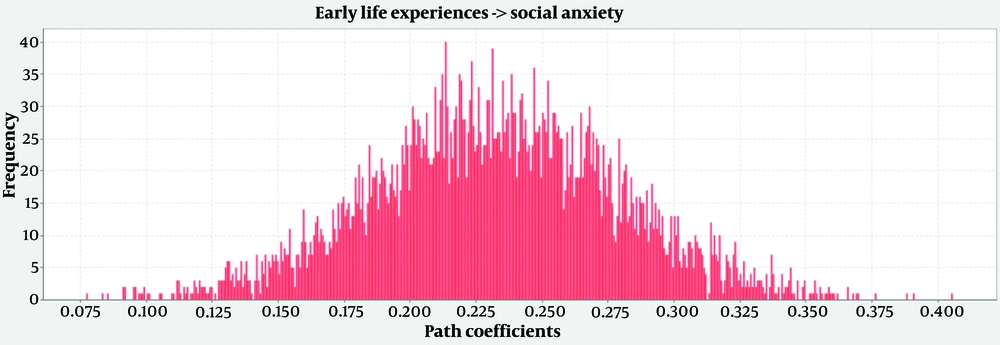

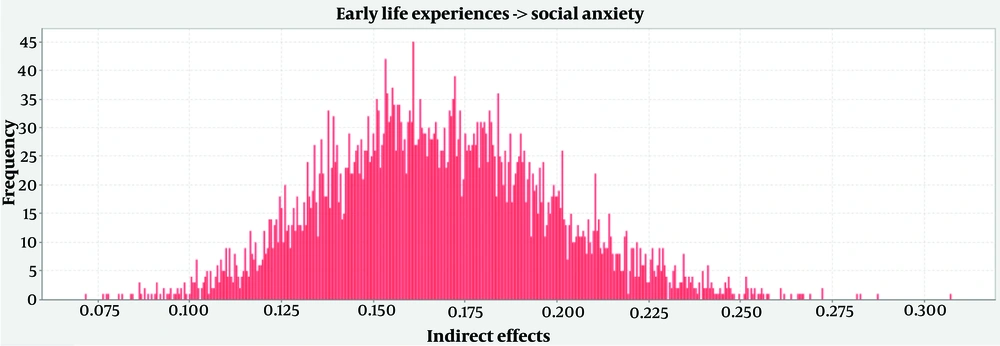

To better understand the coefficients found in the mediation model, Figures 2 and 3 display histograms of the predicted variance of social anxiety based on negative memories of early life experiences. Figures 2 and 3 provide visual representations of variance predictions and indirect effects, respectively. Accordingly, the dispersion of the prediction of the variance of social anxiety in the direct path of early life experiences is greater than in the indirect path, as observed in the histogram.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the mediating relationship between shame and self-criticism based on early experiences with social anxiety utilizing Elliott and Shahar's emotion-focused approach model. The results indicated that negative memories of early life experiences, shame, and self-criticism have a positive and significant correlation with social anxiety.

The results of the sequential mediation model showed that shame and self-criticism significantly mediate the relationship between early life experiences and social anxiety. This suggests that self-criticism forms as a coping strategy in response to shame caused by negative memories of early life experiences, thereby predicting social anxiety. The findings demonstrated that early life experiences, which are not necessarily traumatic, also lead to the development of shame and self-criticism. This research result is consistent with the study by Shahar et al., which showed in a sequential mediation model that emotional abuse predicted shame proneness, which in turn predicted self-criticism, which subsequently predicted social anxiety symptoms (19). Additionally, these findings align with the results of a study by Binelli et al., which showed that family violence has a positive and significant relationship with social anxiety, but experiences of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse had no significant relationship with social anxiety (34). Furthermore, the research results of Asmari et al. indicated that early negative memories of life predict social anxiety symptoms through shame (35).

To explain this finding, according to Elliott and Shahar's model of conceptualizing social anxiety in EFT (12, 14), traumatic memories lead to the internalization of a shame-based cognitive-emotional scheme, which is central to this disorder. These shameful memories are characterized by feelings of inferiority and worthlessness. In adulthood, the shame-based scheme is quickly activated, leading to the well-known phenomenology of social anxiety. Self-criticism plays an essential role in maintaining social anxiety. It operates before, during, and after social situations, with all three types of performance designed to minimize or avoid social risks, exposure to failure, and activation of shame. At the same time, self-critical attacks are embarrassing in themselves. A self-deprecating comment like "If you say something in class, everyone will see how stupid you are" also protects against exposure to failure and embarrassment. Thus, there is a cyclical process whereby efforts to regulate shame also maintain it (14).

The hypothesis regarding EFT for social anxiety posits that early childhood experiences remain in the person's mind as a memory of personal feelings or emotional memory of family relationships in the form of emotional schematic memory and are the source of pain and emotional schemes. To cope with chronic feelings of pain, the person develops a watchful coach/critic/guardian (CCG) aspect in the form of a self-organization (14).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study corroborate the conceptual model proposed by Elliott and Shahar, which frames social anxiety from an emotion-focused perspective. The results indicate that shame and self-criticism are integral factors in the development and conceptualization of social anxiety (14). Additionally, the data suggest that early life experiences directly and indirectly (through the mediating roles of shame and self-criticism) predict social anxiety. One of the most important results of this research was that, unlike previous studies that emphasized the role of traumatic experiences in the formation of shame and social anxiety, this study showed that early life experiences, such as the devaluation of feelings, can lead to shame and, in turn, predict self-criticism and social anxiety.

5.2. Treatment Implications

The study highlights the significance of targeting shame and self-criticism in treating social anxiety, suggesting these as potential focal points for therapeutic intervention. Addressing these factors could improve existing cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs) or contribute to the development of new treatment methods. This approach aims to access and restructure maladaptive, shame-based schemas stemming from earlier abuse experiences. Incorporating such strategies into CBT, particularly as a specialized module, could benefit socially anxious patients with pronounced self-criticism and perfectionism.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions

The convenience sampling method and the selection of student (non-clinical) samples make it difficult to apply and generalize the findings to the broader population, and the results should be interpreted and generalized with caution. Furthermore, the EFT approach, which is based on a neo-humanistic model, emphasizes the client's phenomenal world in its explanation of social anxiety. Consequently, the use of standardized questionnaires to measure primary and secondary emotions, as well as the emotional schema of shame, may not adequately capture the unique characteristics of the client's phenomenal world of experience. It is recommended that this pathological model for social anxiety be examined further through qualitative research and that a treatment protocol be developed based on these findings. It is also suggested to use longitudinal studies instead of cross-sectional designs to evaluate causal effects over time.