1. Context

The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), defines non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) as intentional, socially unacceptable behavior in which an individual harms their body to relieve emotional distress (1, 2). This behavior includes actions such as cutting or burning the skin, often undertaken to alleviate emotions or attract attention. The motivations for this behavior typically include reducing mental pressure, controlling emotional distress, or escaping life problems (1). However, NSSI can become addictive and dangerous, potentially leading to suicide (3). Additionally, self-harm may result in incorrect learning of stress management methods, increased feelings of guilt, depression, and ultimately, exacerbation of primary mental illnesses (4). Several factors, such as depression, stress, low self-esteem, family problems, peer influence, and sexual or physical abuse, are primary contributors to self-harm (5). Treatment for this behavior requires various approaches, including parent training, brief skills training, and behavioral therapies (6). Research indicates that NSSI has become more prevalent in recent decades, with a higher prevalence than suicide in some clinical and non-clinical groups (7). Studies have shown that NSSI is prevalent in more than 4% to 6% of the general adult population and between 5.7% and 8.4% among soldiers (8, 9). The lifetime prevalence of NSSI is estimated at 5.9%, with 2.7% of individuals experiencing injuries more than five times. Furthermore, 0.9% reported NSSI in the past year (10). In Korean youth, NSSI prevalence ranges from 11% to 39%, exceeding actual suicide rates (11). Among medical students in Rawalpindi, NSSI prevalence was reported at 28.4%, with higher rates in males (54.5%) compared to females (45.4%) (12). In South Asia, self-harm behavior prevalence ranges from 3.2% to 44.8% in non-clinical populations and from 5% to 16.4% in clinical populations, indicating a significant burden (13). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of NSSI in non-clinical samples reached 22.5%, with a higher prevalence of 32.40% in adolescents compared to adults (14, 15). A study in Iran reported that the prevalence of self-harm among Iranian youth varies between 4.3% and 40.5%, underscoring the importance of this behavior in mental health (16).

2. Objectives

Given the high costs associated with NSSI for the health system and its incompatibility with societal values and cultural standards, a more thorough investigation of NSSI is necessary. Although extensive research has been conducted in this field, there remains insufficient information about the prevalence and characteristics of NSSI in the Iranian population. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of NSSI in the Iranian population, aiming to provide appropriate and timely interventions in the future and to help manage this problem more effectively.

3. Evidence Acquisition

In the present study, a systematic review and meta-analysis regarding the prevalence of NSSI in the general population in Iran were conducted. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist was utilized for this study (17)

3.1. Search Strategy

The following [MeSH] terms were used across various databases: Prevalence, epidemiology, Iran, self-injurious behavior, and self-mutilation. International electronic databases included Scopus, PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, IMBIS, Cochrane, and PsycINFO. National databases used were Iran Medex, Mogiran, and SID. Searches encompassed all available data until the end of June 2024. A gray literature search was also conducted using Google Scholar. Keywords for both domestic and international databases included self-destruction, self-mutilation, self-injury, intentional poisoning, self-punishment, self-hitting, self-immolation, self-harm, nail-biting, scratching, and self-cutting (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). References in retrieved articles were also searched. EndNote X7 software was used to manage the collected information, and duplicate articles were automatically removed. Articles were examined separately by two researchers.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

We included in this study all observational (cross-sectional) studies that address NSSI in the general population linked to Iran, without imposing a publication time limit. The study population consisted of both men and women. All included studies were required to report NSSI rates in the general population. Several types of studies were excluded, including case reports, case series, reviews, and meta-analyses. Additionally, studies that did not report sample sizes were excluded from this meta-analysis. It should be noted that because suicide attempts are considered distinct from NSSI (18, 19), we also excluded studies that categorized suicide attempts as NSSI to ensure a pure prevalence of NSSI. The term "general population" refers to random sampling from a non-clinical and non-self-harming group within the normal community. Participants did not have any of the following risk factors: Psychiatric diseases (such as depression), hospitalization in service organizations (such as welfare), stressful conditions (such as living on the streets), or family problems (such as divorce).

3.3. Quality Appraisal

Article quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which includes three parts: Selection (4 questions), comparability (1 question), and outcome (3 questions). The final score is categorized as good quality (three or four stars in selection, one or two stars in comparability, and two or three stars in outcome), fair quality (2 stars in selection, one or two stars in comparability, and two or three stars in outcome/exposure), and poor quality (0 or 1 stars in selection, 0 stars in comparability, or 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure) (20). Appendix 2 in Supplementary File presents the qualitative assessment results.

3.4. Screening of Studies

Two individuals conducted the initial search for studies. A team of two researchers independently screened studies, extracted results, and evaluated the quality control of articles. In cases of disagreement, the team leader provided the final decision.

3.5. Data Extraction

All final articles were selected according to a pre-prepared checklist, which included author names, publication years, study periods, sample sizes, study locations, gender, average age, NSSI types, tools used, and prevalence of NSSI.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) software. The random-effects model was used to estimate the overall prevalence of NSSI, accounting for heterogeneity among the included studies. This model assumes that true effect sizes vary across studies, enabling more accurate estimation despite differences in study design and population characteristics. Heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran’s test and Higgins I2 test. Forest plots illustrated the effect size of each study and the pooled estimates. The term 'General' refers to populations including both women and men, with overall NSSI prevalence reported for the entire population. Studies focusing solely on a specific gender were analyzed separately for NSSI prevalence by gender. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis were conducted, with significant results defined as those with a p-value below 0.05.

3.7. Publication Bias

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger’s weighted regression (21). A P-value > 0.05 indicated no publication bias.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

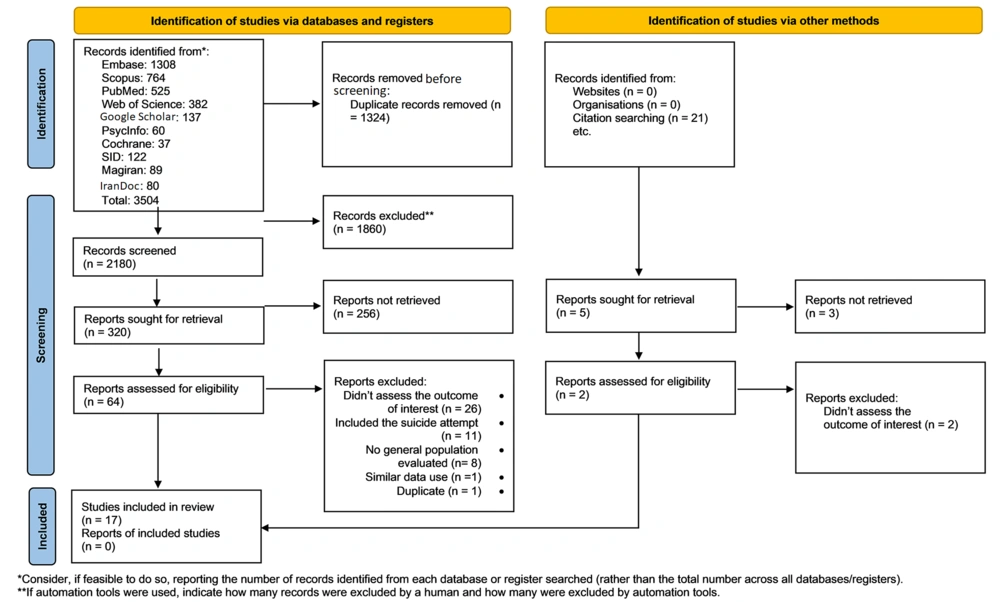

A total of 3504 articles were identified through searches of all national and international databases. After removing duplicate articles, 2180 articles proceeded to the title and abstract screening stage. Subsequently, 64 full-text articles were evaluated, and 17 articles were ultimately selected for analysis. These 17 articles were also reviewed for related studies based on their references. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, including database and other source searches (17)

4.2. Study Characteristics

Among the 17 articles spanning from 2004 to 2024, 16 studies reported the prevalence of NSSI in the general population (both sexes), 7 studies reported prevalence in women, and 6 studies reported prevalence in men. Table 1 presents the descriptive information.

| Authors | Duration of Data Collection | Province (City) | Sex | Instrument for Self-injury Findings | Type of Self-injury | Total Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbasian et al. (22) | 2018 - 2019 | Markazy (Saveh) | Female | Standard instrument | NSSI | 571 |

| Abdollahi et al. (23) | 2018 - 2018 | Gilan (Rasht) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | Self-cutting | 617 |

| Babaeifard et al. (24) | 2024 - 2024 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 1014 |

| Ghanizadeh and Shekoohi (25) | 2008 - 2008 | Fars (Shiraz) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | Nail biting | 460 |

| Gholamrezaei et al. (26) | 2017 - 2017 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 554 |

| Izadi-Mazidi et al. (27) | 2018 - 2018 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 642 |

| Marin et al. (28) | 2017 - 2018 | Western Azerbaijan (Tabriz) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | NSSI | 6229 |

| Mohammadpoorasl et al. (29) | 2005 - 2005 | Western Azerbaijan (Tabriz) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | NSSI | 1772 |

| Mohammadpoorasl et al. (30) | 2010 - 2010 | Western Azerbaijan (Tabriz) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | NSSI | 4903 |

| Mozafari et al. (31) | 2018 - 2019 | Kurdistan (Sanandaj) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 1334 |

| Nemati et al. (16) | 2017 - 2017 | Western Azerbaijan (Tabriz) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | NSSI | 3966 |

| Nobakht and Dale (32) | 2016 - 2016 | Mazandaran (Babol) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 200 |

| Mohammadpoorasl et al. (33) | 2005 - 2005 | Western Azerbaijan (Tabriz) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | NSSI | 1768 |

| Rezaei et al. (34) | 2020 - 2021 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 655 |

| Sabet Dizkuhi and Kafie Masooleh (35) | 2019 - 2020 | Gilan (Rasht) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 508 |

| Taheri et al. (36) | 2019 - 2020 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sexes | Standard instrument | NSSI | 223 |

| Bathaee and Kamali Fard (37) | 2004 - 2004 | Tehran (Tehran-Rayy) | All sexes | Researcher checklist | Nail biting | 18000 |

Basic Information of Included Studies in the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

4.3. Quality Appraisal

Article quality assessment results are shown in Appendix 2 in Supplementary File. According to the review using the relevant scale, all studies were rated as having good quality.

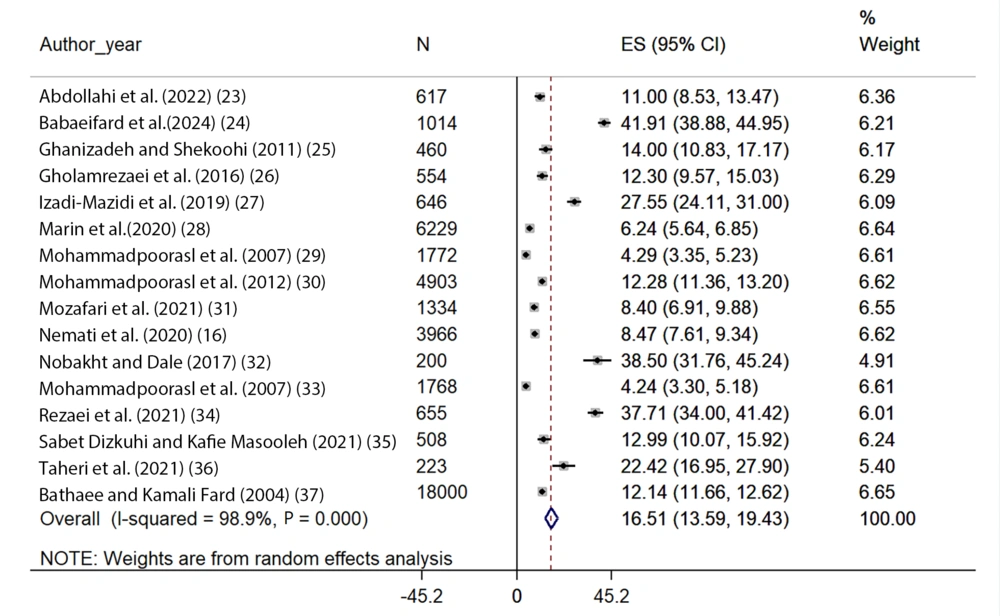

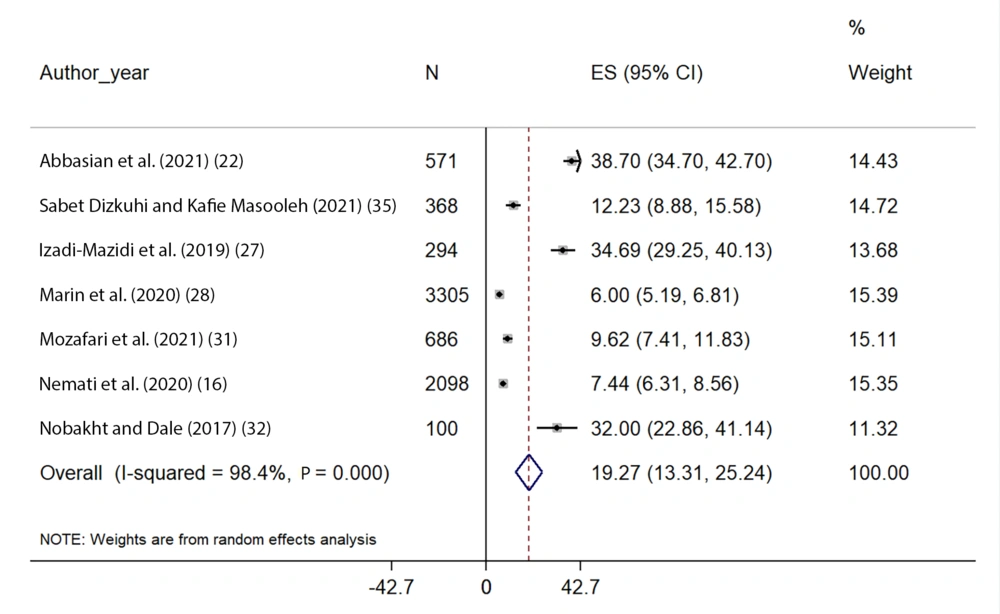

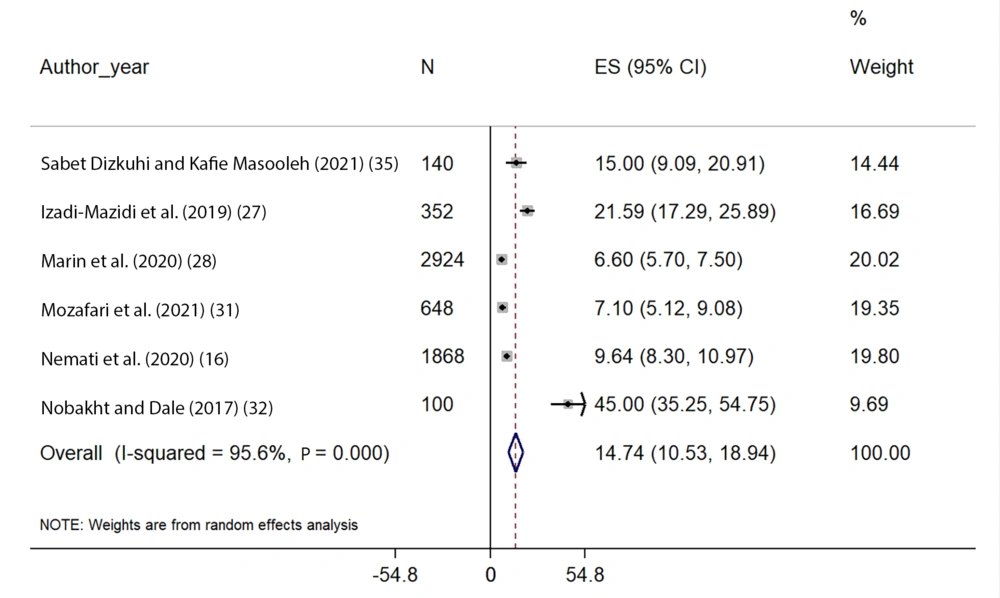

4.4. Heterogeneity

The chi-squared test and I2 Index indicated significant heterogeneity among the studies. In the general population, the heterogeneity of NSSI prevalence was I2 = 98.9% (P < 0.001); in men, it was I2 = 95.6% (P < 0.001); and in women, it was I2 = 98.4% (P < 0.001). Consequently, all analyses were conducted using the random-effects model.

4.5. Meta-Analysis Results

The articles were first sorted by publication year, followed by determining the prevalence of NSSI in both genders and provinces. A meta-regression was also performed based on the study year.

4.6. Prevalence of Non-suicidal Self-Injury in the General Population and by Gender

Sixteen studies reported the prevalence of NSSI in the general population out of a total of 17 articles. Based on the random-effects model, the estimated pooled prevalence of NSSI was 16.51% (95% CI, 13.59 - 19.43) (Figure 2). Seven studies reported the estimated pooled prevalence of NSSI in women as 19.27% (95% CI, 13.31 - 25.24) (Figure 3), and six studies reported the estimated pooled prevalence of NSSI in men as 14.74% (95% CI, 10.53 - 18.94) (Figure 4).

4.7. Meta-Analysis of Subgroups According to Provinces

According to the prevalence of NSSI by province, Tehran province had six studies with an estimated pooled prevalence of 25.54% (95% CI, 14.48 - 36.80), followed by West Azerbaijan province with five studies at 7.10% (95% CI, 4.41 - 9.79), Gilan province with two studies at 11.83% (95% CI, 9.90 - 13.76), and Mazandaran, Fars, and Kurdistan provinces each had one study (Table 2) (Appendix 3 in Supplementary File).

| Provinces | No. of Study | Effect Estimates (Estimated Pooled Prevalence) | 95 % CI | I2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tehran | 6 | 25.64 | 14.48 - 36.80 | 99.2 | < 0.001 |

| Western Azerbaijan | 5 | 7.10 | 4.41 - 9.79 | 98.1 | < 0.001 |

| Gilan | 2 | 11.83 | 9.90 - 13.76 | 3.9 | 0.078 |

| Mazandaran | 1 | 38.50 | 31.75 - 45.24 | - | - |

| Fars | 1 | 14.00 | 10.82 - 17.17 | - | - |

| Kurdistan | 1 | 8.39 | 6.90 - 9.88 | - | - |

| Total | 16 | 16.51 | 13.59 - 19.43 | 98.9 | < 0.001 |

Results of the Meta-Analysis and Heterogeneity of Self-Injury Estimated Pooled Prevalence in the General Population of Iran Based on Province

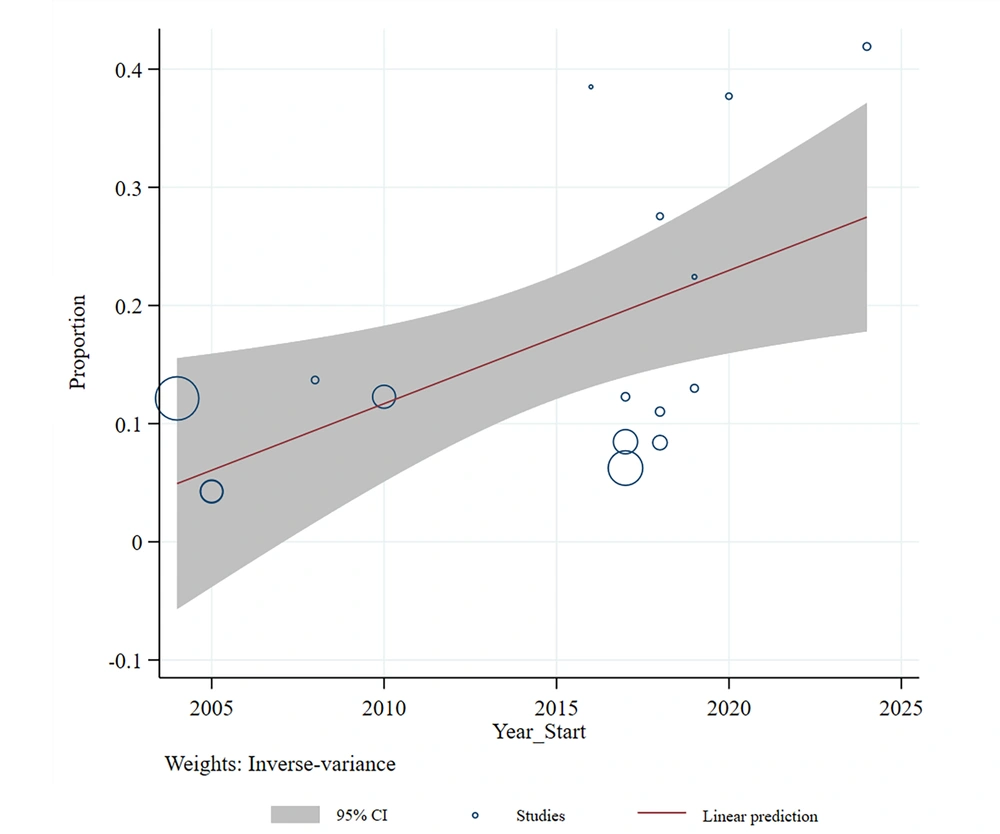

4.8. Meta-regression According to the Years of the Study

The estimated pooled prevalence of NSSI in the general population was related to the years in which the studies were conducted (Reg Coef = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.003 to 0.020, P = 0.011). This indicates that as the years progressed from the earlier years (2004) to the more recent years (2024), the estimated pooled prevalence of NSSI in the general population significantly increased (Figure 5).

4.9. Publication Bias

Finally, funnel plots were drawn to assess publication bias for the prevalence of NSSI in the general population. This bias was not confirmed by the Egger test (bias for total: -0.73, 95% CI = -12.82 to 11.34; P = 0.897) (Appendix 4 in Supplementary File).

5. Discussion

In this study, the estimated pooled prevalence of NSSI in the general population of Iran was calculated as 16.51%. This prevalence was higher in women (19.27%) than in men (14.74%), highlighting the importance of gender differences in this behavior. Various studies worldwide have reported a high prevalence of NSSI, ranging from 17% to 38% (38-42). As suggested by Ghaedi Heidari et al. (43), this gender difference may be attributed to distinct coping mechanisms employed by men and women in response to stress and psychological difficulties. Women may be more likely to express emotional distress through self-harming behaviors, whereas men may employ different, potentially less visible, coping strategies. However, the study by Izadi-Mazidi et al. in Tehran did not find significant gender differences in the prevalence of NSSI, indicating that in some contexts, gender may not be the sole determining factor for self-harm behavior (27). This discrepancy emphasizes the need for region-specific research that accounts for local socio-cultural conditions, which may mediate or mitigate gender differences in self-injury rates.

Furthermore, a 2023 review study corroborates our findings, demonstrating that the global prevalence of NSSI varies widely, ranging from 11.5% to 33.8%, influenced by sample types and study designs. This review also observed a rising trend in NSSI, particularly in developing countries, which aligns with the findings of our study. While NSSI is prevalent in both developed and developing countries, the socio-cultural and economic factors contributing to this behavior may differ across regions (44). In developed Western countries, the focus is often on individual mental health conditions, whereas in developing nations like Iran, a complex interplay of socio-economic stressors, cultural taboos, and limited access to mental health care may contribute to the growing prevalence (45).

The increasing trend of NSSI in adolescents, as reported by Sahay and Nilanjana and seen in other studies, underscores the importance of addressing the psychological and social factors driving this behavior, particularly in younger populations (46). The lack of adequate mental health services, high levels of economic stress, and societal pressures could exacerbate these issues, especially in countries like Iran, where social stigma around mental health may deter individuals from seeking help. Therefore, the findings of our study call for targeted preventive and therapeutic interventions that are culturally sensitive and socioeconomically appropriate.

It should be noted that the socio-cultural and economic landscape of Iran plays a pivotal role in the prevalence and nature of NSSI. The societal emphasis on conformity and the stigma associated with mental health issues often prevent individuals from openly addressing psychological distress. Women, in particular, may be more susceptible to NSSI as a means of coping with the societal pressure to fulfill traditional roles, which may heighten emotional and psychological burdens. Economic factors, such as unemployment, financial insecurity, and the rising cost of living, further compound mental health challenges, particularly among vulnerable populations. In regions like Tehran, where urban stressors are more pronounced, the prevalence of severe self-harm methods, such as cutting, is higher, reflecting the intensifying pressures faced by individuals in urban settings. In contrast, rural areas, like Gilan, may report lower rates of severe self-harm, which could be attributed to a combination of less exposure to mental health stigma, fewer healthcare resources, and different coping mechanisms prevalent in more rural, community-oriented environments. Moreover, the limited availability of mental health services, coupled with the growing economic and social challenges in Iran, exacerbates the situation, contributing to the underreporting and lack of early interventions for NSSI. Therefore, expanding access to mental health care, reducing stigma, and addressing the socio-economic conditions influencing self-harm behaviors are crucial steps toward improving mental health outcomes in Iran.

In line with the present study, the study by Akbari et al. in 2024 also showed that the prevalence of NSSI is higher in women than in men (47). In another study conducted in Iran, the prevalence of NSSI in male and female adolescents was reported as 26.8% and 17.9%, respectively (48). Evidence shows that this behavior is more common in girls. These differences could be related to psychological, cultural, and social factors (49-52). In a study conducted by Abbasian et al. in Iran in 2021, the prevalence of NSSI in women was 17.51%, higher than in men (22). A prevalence rate of 27.6% was reported in European countries. The most prevalent NSSI incidences were reported in Estonia, France, Germany, and Israel, while the lowest prevalence rates were reported in Hungary, Ireland, and Italy (53). It was more in women than in men, which is consistent with the findings of this study. These differences in NSSI prevalence between genders may be influenced by various psychological and social factors. Women are generally more likely to internalize emotions and distress, which can lead to higher rates of self-harming behaviors. Additionally, gender roles and societal pressures may contribute to this disparity, with women often facing more emotional stress due to expectations related to caregiving and emotional expression. Social factors, such as gender inequality and higher exposure to interpersonal violence, can also increase the risk of NSSI in women (40). Further research is needed to explore how these factors interact to contribute to the gender differences observed in NSSI prevalence.

As observed in this study, regional variations in the prevalence of NSSI across Iran are significant. Tehran had the highest prevalence rate at 25.64%, while provinces like Western Azerbaijan and Gilan reported lower figures. These differences are likely influenced by various cultural, economic, and social factors that merit further investigation. For example, a study by Babaeifard et al. reported an exceptionally high NSSI prevalence of 41.91% in Tehran’s general population (24). In contrast, studies by Mohammadpoorasl et al. and Mozafari et al. found much lower prevalence rates of under 10% in Western Azerbaijan and Kurdistan (31, 33). These discrepancies may stem from regional differences in healthcare access, social support systems, cultural attitudes towards mental health, and other socio-economic factors. Further research is essential to understand these regional differences more comprehensively and to develop targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

Moreover, the type of self-harm methods used may also contribute to these regional variations. Although data on self-harm methods were available from only three studies, certain patterns emerged. Specifically, Ghanizadeh and Shekoohi (25) and Bathaee and Kamali Fard (37), both conducted in Tehran and Fars, reported higher NSSI prevalence compared to Abdollahi et al. (23), which focused on self-cutting in Gilan. These findings suggest that more severe self-harm methods, such as cutting, are associated with higher prevalence rates of NSSI. Geographic factors, including access to mental health care, healthcare infrastructure, and cultural attitudes, may further explain the observed differences in both self-harm methods and NSSI prevalence. Additionally, socio-economic conditions in each province could influence not only the occurrence of NSSI but also the choice of self-harm methods. For instance, urban areas like Tehran may experience more severe forms of self-harm due to higher stress levels, greater availability of means, and distinct cultural norms compared to rural areas such as Gilan. More research is needed to explore the relationship between geographical conditions, self-harm methods, and NSSI prevalence, which will facilitate the development of more effective, region-specific interventions.

5.1. Conclusions

Self-injury is considered a serious mental health issue in Iran, requiring special attention. The high prevalence of this behavior, especially in some provinces and among women, indicates the necessity of designing and implementing preventive and therapeutic programs that focus specifically on these groups. The increase in NSSI prevalence in new studies also indicates that more research should be done to identify the reasons for its increasing trend. This should be done to design timely interventions.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Given the high prevalence of NSSI in the Iranian population, particularly among women and in certain provinces, it is crucial that future research explores the psychological, social, and cultural factors contributing to this behavior. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term impacts of interventions aimed at reducing NSSI. Additionally, further investigation into the increasing prevalence of NSSI, especially in light of recent societal changes, will help inform the development of targeted prevention and treatment programs.

5.3. Strengths and Weaknesses

This study used meta-analysis to combine different data, which increased the accuracy of the results. Additionally, the geographical diversity of this study provides a more comprehensive viewpoint of this behavior in the country. Furthermore, women and men have been analyzed separately for differences in the prevalence of NSSI. This information may help future treatment and prevention plans to be more effective. However, the number of studies in some provinces was small and may not be a proper representative of the prevalence rate of NSSI in those regions. For example, some provinces had only one or two studies, and some provinces had none. The NSSI prevalence was correlated with the year of study, but changes in social and psychological conditions during these years were not fully explored. Therefore, considering these weaknesses, it is suggested to collect more data from less studied or unstudied provinces and analyze social and psychological changes in more detail in future research. By using these measures, we can better understand the factors affecting NSSI prevalence and improve therapeutic interventions.