1. Context

In recent years, studies have highlighted a growing prevalence of mental health issues among children and adolescents (1). The global prevalence of these mental health problems is estimated to be between 10% and 20% (1, 2). Notably, approximately 70% of symptoms associated with clinical disorders manifest before the age of 18, underscoring the significant impact of mental illness during critical developmental years (3). Psychopathology is frequently associated with poor emotional regulation. The capacity to regulate emotions begins to develop in infancy when children primarily depend on their caregivers for emotional support (4, 5).

Recently, researchers and therapists have increasingly focused on the role of emotions in psychological issues, confirming that changes in the mechanisms of emotion regulation can significantly impact mental health (6-8). Various approaches aimed at mitigating psychological harm by addressing emotional issues have been explored. One notable approach that has gained traction in recent years is emotion-focused therapy (EFT). Emotion-focused therapy is a humanistic, experiential, process-oriented, and transdiagnostic approach grounded in the belief that mental illness arises when emotions cease to function adaptively (9). This therapy integrates principles from client-centered therapy — such as unconditional positive regard, empathy, and authenticity — with Gestalt techniques (e.g., two-chair and empty chair dialogues) and other experiential methods. The goal is to elicit core maladaptive emotions (e.g., shame, fear), transform them by fostering adaptive emotional responses (e.g., assertive anger, sadness, compassion), and promote healthier relationships (10, 11).

Emotion-focused therapy has demonstrated effectiveness across diverse client populations and various psychological issues, including depression, complex trauma, and anxiety (12, 13). While EFT can be considered a transdiagnostic approach (14), there remains a need to understand its effectiveness across different populations and how it enhances community functioning. To enhance our understanding of EFT in relation to child and adolescent mental health issues, this study conducted a scoping review to gather information on the current state of EFT for these populations. We also examined limitations within the field and proposed solutions to address these challenges. Scoping reviews summarize existing studies on a given topic to identify problems and future directions (15).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to answer the following questions:

1. In what ways have EFT interventions been utilized with children and adolescents (e.g., individual, group, and family therapy)?

2. What mental health outcomes are reported in the findings of these studies?

3. How has EFT been adapted to improve mental health outcomes for children and adolescents?

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study employs a scoping review methodology. Two researchers conducted a systematic search, selection, and synthesis of information relevant to the research questions within a specified time frame, following the framework outlined in previous literature (16). The study was conducted in the following steps: (1) identifying relevant studies; (2) selecting appropriate studies; (3) extracting data and (4) collecting findings, summarizing, and reporting results (17).

3.2. Search Strategy

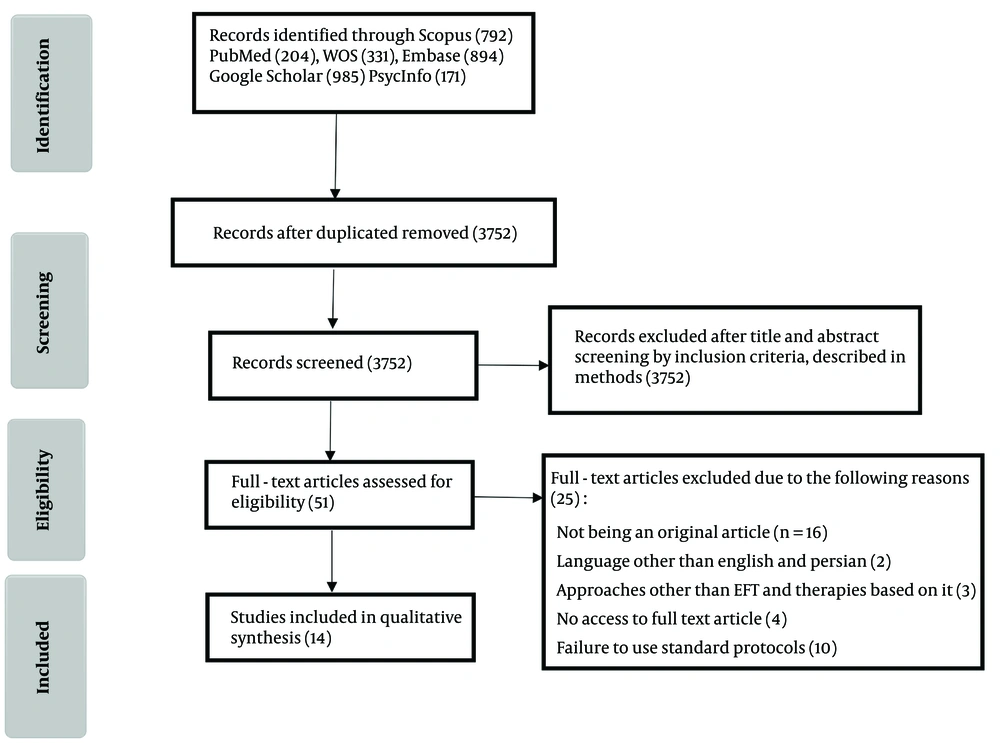

Six databases were searched for this scoping review: Scopus, Web of Science (core collection), PubMed/Medline, Embase, Google Scholar, and PsycInfo (via EBSCO). Keywords were derived from subject headings such as MeSH and EMTREE, as well as from reviews of similar studies and input from subject matter experts. The keywords included: "Emotion-Focused Therapy", "Emotion-Focused Therapies", "Therapy", "Emotion-Focused" and "Process-Experiential Therapy". The search strategy was tailored to the specific characteristics of each database, and studies published up until December 2024 were included. The outputs from the databases were managed using EndNote version X8 software. The screening process for published studies involved two steps: (1) screening titles and abstracts and (2) conducting a full-text review.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) studies based on the EFT approach (individual, group, or family therapy); (2) studies reporting at least one mental health outcome related to children and adolescents; (3) descriptive, review, experimental, or mixed-method studies; (4) articles published in English; (5) no time limit on the publication date of articles.

The following criteria were used to exclude studies from the review: (1) studies employing methods other than EFT; (2) studies focusing on mental health outcomes in populations outside of children and adolescents; (3) full texts that were unavailable; (4) articles published in languages other than English.

4. Results

4.1. Collection, Summary, and Reporting of Findings

A detailed overview of the search strategies, including the number of articles found in each database is presented in Figure 1. In total, 2,803 articles were identified. After removing 217 duplicate entries, 2,767 articles proceeded to stage 1, which involved title and abstract screening. Through this process, 2,725 articles were excluded. In stage 2, the remaining 41 articles underwent a full-text review, leading to the exclusion of an additional 27 articles, resulting in a final count of 14 articles (Figure 1). Data collected from the eligible articles included the following information: Author’s last name, year of publication, country, study type, setting, participant demographics (including mean age), intervention delivery method (individual, group, or family), mental health outcomes (psychological, organized into psychiatric, social, etc.), measurement tools used, and results (Table 1).

| Authors, Year, Country | Type of Study | Study Location | Sample Size /Gender | Average Age | How to Use the Intervention | Name of the Intervention (if, any) and its Components | Number of Sessions | Mental Health Outcome/Assessment Tool | Evaluation Stage/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloch and Guillory, 2011, America (18) | Descriptive | Treatment room | 1/girl | 13 | Different combinations of family members | EFFT/humanistic and experiential approach + systemic approach | 31 | Behavioral-emotional problems at school/school report and therapist diagnosis | Before and after intervention/changes in family interactions, increased emotional self-awareness, distress tolerance, self-confidence |

| Knatz et al., 2015, America (19) | Descriptive | - | 1/girl | 16 | Caregiver sessions (uncle) | EFPT-EE/principles-based EFT + EFFT | 8 | Bulimia nervosa, depression | Before and after intervention/reduction in depressive symptoms and weight loss |

| Robinson et al., 2015, Canada (20) | Descriptive | - | 1/girl | - | Parent sessions | EFFT/fundamentals-based EFT + FBT | - | Anorexia nervosa and loss of social functions/expert diagnosis | Before and after intervention/disappearance of symptoms and increase in social functioning |

| Lafrance Robinson et al., 2016, Canada (21) | Mixed method | 24 | 24 | 18 | Parent group sessions/ caregivers | EFT-based EFFT for eating disorders | Two-day workshop | Semi-structured interview | Supporting the restoration of the parent-child relationship |

| Foroughe et al., 2019, Canada (22) | Clinical trial | Large meeting room in a health center | 90 | 18 | Parent group sessions/caregivers | EFFT/consists of family-based therapy (23), motivational interviewing (24) and EFT (25) | Two-day workshop | Types of mental health problems other than psychosis/CBCl | Study with control group/before, after and 4 months after intervention/significant improvement in symptoms |

| Robinson, 2020, England (26) | Mixed method | - | 2 girls/1 boy | 14 | Teen group sessions | EFGT with autistic adolescents/based on EFT principles | 11 | DSM-IV and the CEPS-AS | Improving emotion processing, discovering self-agency in interpersonal ruptures, and strengthening self-esteem and increasing cognitive-emotional empathy. |

| Wilhelmsen-Langeland et al., 2020, Norway (27) | Clinical trial | - | 9 boys/8 girls | 8.71 | Parent/caregivers group sessions | EFFT/based on the models of Foroughe et al. (22), LaFrance Robinson (28), Strahan et al. (29) | Two-day workshop | Mental health problems/CBCl | Baseline, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up /improvement in internalizing and externalizing symptoms |

| Ansar et al., 2022, Norway (30) | Clinical trial | Two mental health clinics | 93 boys/50 girls | 8.92 | Parent/caregivers group sessions (group-individual) | EFST/based on EFT two versions: (1) based on the principles of experiential therapy and (2) version based on psychoeducation | 2-day group training and 6 hours of individual supervision | Externalizing and internalizing problems/ BPM, BPM-P and BPM-T | Before and after intervention and follow-up at 4, 8, and 12 months/reduction in child’s symptoms at 12-month follow-up intervention/disappearance of symptoms and increase in social functioning |

| Cordeiro et al., 2022, Canada (31) | Clinical trial | Family Mental Health Center | 170 | 10.80 | Parent/caregivers group sessions | EFFT/Based on the model presented by LaFrance Robinson | Two-day workshop | Mental health problems/emotion regulation questionnaire and behavioral and emotional problems in children | Reducing negativity, instability, and emotional and behavioral problems in children |

| Foroughe et al., 2022, Canada (32) | Descriptive, presenting the online EFFT model | Virtual platform/video conferencing platform | - | - | Parent/caregivers group sessions | Online EFFT/adapted form of the model used in Foroughe et al.’s study (32) for virtual sessions | Two-day workshop | Consequences of children’s mental health | - |

| Foroughe et al., 2023, Canada (33) | Clinical trial | Family Psychology Center | 179 boys/156 girls | Boys 9.90/girls 12.12 | Parent/caregivers group sessions | EFFT/consists of family-based therapy (23), motivational interviewing (24) and EFT (25) | Two-day workshop | Mental health problems/Goodman Strengths and Weaknesses Questionnaire (34) | One week before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and at 4, 8, and 12-month follow-ups; reduction in symptoms at follow-ups |

| Robinson and Yong, 2023, Canada (35) | Qualitative study | - | - | - | Parent/caregivers group sessions | EFFT and a customized training program for parents of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders RU | Two-day workshop | - | Main extracted theme: Discovering painful stimuli and repairing the autistic parent-child relationship |

| Smith et al., 2023, Canada (36) | Case study | Get A-Head video conferencing platform virtual platform | - | 8 | Parent/caregivers group sessions | EFT-based EFFT | 8 | Anger, depression, and anxiety/Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) | Before and after intervention/reduce symptoms of anger, depression, and anxiety |

| Ansar et al., 2024, Norway (37) | Clinical trial | Two mental health clinics | 136 | 143; 8.9 boys/93 girls | Group-individual for parents with two experimental methods and psychoeducation | EFST/based on EFT two versions: (1) based on the principles of experiential therapy and (2) version based on psychoeducation | 2-day group training and 6 hours of individual supervision | Externalizing and internalizing problems/ BPM, BPM-P and BPM-T | Before and after intervention and follow-up at 4, 8, and 12 months/reduction in child’s symptoms at 12-month follow-up/reduced symptoms in children resulting in improved outcomes for parents |

Abbreviations: EFGT-AS, emotion-focused group therapy with autistic adolescents; EFST, emotion-focused skills training; BPM, brief problem monitor; BPM-P, brief problem monitor for parents; BPM-T, brief problem monitor for teachers; RU, relationships and understanding for parents of teenagers on the autism spectrum; PROMIS®: Patient‐reported outcomes measurement information system; EFFT, emotion-focused family therapy; EFGT, emotion-focused group therapy; EFPT-EE, emotion-focused parent training for adolescents with eating disorders; EFT, emotion-focused therapy; CBCl, Child Behavior Assessment Checklist; CEPS-AS, the emotional processing scale for autism spectrum disorders; DSM, diagnostic and statistical manual.

4.2. Study Characteristics

Among the 14 studies analyzed, four were descriptive (18, 19, 21, 32), six were clinical trials (22, 27, 31, 33, 37, 38), one was qualitative (35), two were mixed-method studies (21, 26), and one was a case study (36). Among the included studies, one study (26) focused directly on adolescents, while the remaining eleven studies targeted parents and assessed outcomes for children and adolescents indirectly. One study (32) proposed a model for implementing emotion-focused family therapy (EFFT) virtually, and another study (35) offered a model of EFFT for working with parents of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Sample sizes across these studies varied from 1 to 337 participants, with ages ranging from 8 to 18 years. Eight studies were conducted in Canada (20-22, 31-33, 35, 36), one in the UK (26), two in the US (18, 19), and three in Norway (27, 30, 37) (Table 1).

4.3. Outcomes of Children and Adolescents and Measurement Tools

Outcomes concerning children and adolescents encompassed eating disorders (19), emotional reactions related to anxiety and depression, somatic complaints, social withdrawal, sleep disturbances, aggressive behavior, social difficulties, intellectual challenges, attention deficits, legal infractions, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (22, 27, 31, 36-39). Additionally, some studies explored psychological outcomes, including emotional self-awareness, distress tolerance, self-esteem, emotional processing, and emotional regulation (18, 26, 31). Social and relational functioning was also assessed, examining competencies in activities and school performance as well as interpersonal challenges with peers (18, 20, 27, 33). Outcomes were evaluated in six studies (22, 26, 27, 30, 31, 33, 37) utilizing standardized measurement scales, while the remaining studies employed various other methods, such as interviews, expert assessments, and reports from parents and schools (Table 1).

4.4. Intervention Implementation Method

One study utilized EFT in the format of emotion-focused group therapy (EFGT) specifically for adolescents and assessed their outcomes directly (26). Three studies incorporated EFFT, which included sessions for parents (19, 20, 36), while six additional studies applied EFFT that featured parent group workshops, indirectly measuring outcomes for both children and adolescents (21, 22, 27, 31, 33). One study implemented EFT within a family therapy context, involving varying combinations of family members, including three mother-daughter sessions, one father session, two mother-father sessions, and the remaining sessions involving the daughter (18). Two studies executed two-day parent group workshops complemented by individual sessions (30, 37). Additionally, two models were specifically designed around two-day parent group workshops (32, 35). Several studies have reported the pre- and post-intervention effects descriptively (18-21, 26). Among these, six studies included follow-up assessments conducted 3 to 12 months after the intervention (22, 27, 30, 31, 33, 37), as summarized in Table 1.

4.5. Number of Sessions and Providers

The interventions that were delivered in the format of group family therapy typically consisted of 2-day workshops (21, 22, 27, 30, 31, 33, 35). The majority of the interventions were facilitated by trained expert providers (21, 22, 26, 30, 31, 33, 36, 37). Notably, one intervention was administered by a newly trained EFFT practitioner under the supervision of a senior EFFT therapist (18). However, in three studies, the qualifications of the providers were not specified (19, 20, 27) (Table 1).

4.6. Target Population

The eligible studies included a total of 1,117 children and adolescents from diverse populations, with sample sizes ranging from 1 to 337 (Table 1).

4.7. Intervention Delivery Settings

The interventions identified were implemented in a variety of settings, including treatment rooms in clinics and psychological centers (18, 30, 37), health centers (22, 31), and one study was conducted in both a virtual setting and the Get A-Head videoconferencing platform (22, 31, 36). Additionally, the model designed by Foroughe et al. (2022) was generally an adapted form of EFFT intended for delivery in a virtual space (32) (Table 1).

4.8. Interventions Implemented and Their Components

All interventions were developed based on the principles of EFT. A comprehensive list of the components of these interventions is provided in Table 1.

5. Discussion

The present scoping review aimed to examine studies focusing on EFT-based interventions that targeted at least one mental health outcome or emotional-behavioral issue in children and adolescents, or that reported relevant outcomes for this demographic as secondary findings. A total of 12 studies were identified that demonstrated the effects of EFT-based interventions on outcomes for children and adolescents. Additionally, two studies presented models of EFT-based interventions tailored for child and adolescent outcomes, including one study that detailed an online adaptation of EFFT specifically addressing mental health challenges in this population (32). Another was a qualitative study that presented an adapted form of EFFT to identify painful stimuli and repair the relationship between parents of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (35).

As shown in Table 1, EFT has been implemented in relation to children and adolescents’ problems until 2016 mainly in the form of EFFT with different methods (different combinations of family members, parent meetings, and parent group workshops) only for eating disorders. Since then, it has been used in a wider range of mental health problems and behavioral-emotional components of children and adolescents. However, there is still a gap in studies focusing on different populations of children and adolescents (including those involved in acute physical problems, injuries caused by accidents, social and family injuries, etc.), and different outcomes specifically in various communities of children and adolescents can be of interest to researchers in future studies.

More than half of the studies identified in the databases reviewed were conducted in Canada, the birthplace of EFT, and all but nine studies were conducted in the Americas and three in Europe (Norway, England). Since almost all studies were conducted with various adapted forms of EFFT tailored to the study population, and it is evident that family structure in terms of culture, ethnicity, religion, society, and cognitive and emotional patterns in different societies can have specific differences that affect the effectiveness of treatment, this scoping review clearly shows the gap in studies in different geographical, cultural, ethnic, etc., communities.

Based on our findings, with the exception of one study (26) that applied EFT in a group setting to assess outcomes for adolescents, the majority of the remaining studies utilized EFT as an EFFT approach that involved working primarily with parents. This has included formats such as parent meetings and parent group workshops, focusing on outcomes related to children and adolescents within this therapeutic framework. This trend underscores that current knowledge regarding the impact of EFT and its associated interventions within the child and adolescent population is notably limited; most outcomes explored have been derived from interactions with parents rather than from direct assessments with children or adolescents themselves.

In most of the included studies, outcomes for children and adolescents were measured through standardized questionnaires completed by parents, and occasionally by teachers (30, 37), or were reported by parents. Additionally, in two studies, outcomes for children or adolescents were noted as secondary outcomes within the qualitative sections of the research. This reliance on parental reports highlights a significant gap in independent assessments from adolescents, particularly concerning their own perspectives on their outcomes. Such a limitation could potentially influence the findings of these studies.

Moreover, most interventions were conducted by trained and experienced practitioners, some of whom were the original developers of EFFT, with the exception of one study that involved a newly trained practitioner working under supervision. This observation is encouraging and supports the credibility of the research methodologies employed. By addressing their methodological limitations, most of these studies can provide a solid framework for examining various outcomes in children and adolescents. Notably, only six studies have been executed as clinical trials incorporating multi-month follow-ups to investigate the effects of EFT-based treatments on mental health outcomes in this demographic. This suggests that the application of this therapeutic approach in the child and adolescent population is still in its early stages and highlights the pressing need for additional studies with extended follow-up periods to fully explore its efficacy.

The components and goals of treatment in most studies have been specifically tailored to the populations being examined. For instance, among the studies reviewed, Robinson’s intervention (40), which is grounded in the theoretical principles of EFT and adapted from EFFT, is called emotion-focused parent training for adolescents with eating disorders (EFPT-EE). This intervention aims to disrupt harmful eating behaviors by empowering parents, based on the EFT principle that caregivers play a crucial role in fostering healthy emotional development through their responses to their child’s emotions during pivotal developmental stages. Typically, caregivers who are attuned to their child’s emotional states and respond to various emotions in validating and constructive ways promote healthy emotional functioning throughout an individual’s lifespan. In contrast, maladaptive or disorganized responses can lead to the development of unhealthy emotional coping mechanisms and emotional dysregulation (28).

Consequently, EFPT-EE encourages parents to adopt the role of their child’s "emotional coach", guiding them to recognize overeating as a manifestation of emotional dysregulation (19). In other studies reviewed, interventions have similarly been adapted to align with the population being studied and the specific outcomes of interest. Overall, EFFT, as the most commonly employed approach across various formats of child and adolescent therapy, targets the barriers that obstruct parents from effectively supporting their child’s recovery process. By enhancing parental involvement, EFFT seeks to facilitate positive outcomes, regardless of the child’s age (22).

Given these considerations, there is a strong rationale for investigating the efficacy of explicit parent-based models in treating children and adolescents facing a range of mental health issues. High levels of caregiver stress and low self-efficacy among caregivers have been shown to hinder treatment outcomes for children with various mental health challenges (23, 24, 41). Therefore, addressing parents’ emotional responses in their supportive roles can play a vital part in the recovery process for their children (28, 41).

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this scoping review regarding the use of EFT with children and adolescents indicate that the majority of studies were conducted using EFFT through work with parents and caregivers in group workshops, aiming to address outcomes related to children and adolescents. The outcomes studied primarily included eating disorders, emotional reactions associated with anxiety and depression, and emotion regulation problems. It was noted that most studies utilized established protocols in the United States and subsequently in Europe. This suggests that the application of EFT in the context of children and adolescents, as well as the related studies, is still in its early stages.

The findings of this study — concerning the methods of implementing EFT with children and adolescents, the outcomes studied, and how to adapt therapeutic protocols to the target population — can provide a guideline for future research in this field. Based on the findings of this study, further studies on EFT for children, adolescents, and their families are important, as research shows that this approach enhances emotional regulation and interpersonal relationships, and fosters healthier development and resilience. Among the limitations of this study, the lack of access to a few complete articles can be mentioned, which unfortunately led to the exclusion of those papers from the study.