1. Background

Suicide constitutes an important public health concern, with over 800,000 individuals dying by suicide globally each year (1). Each such loss deeply impacts an estimated 60 suicide loss survivors (SLSs), including family, friends, colleagues, and therapists (2). Compared to the general population, SLSs experience heightened risks for suicidal behaviors and psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and PTSD, and are particularly susceptible to developing prolonged grief symptoms (PGS) (3). Prolonged grief disorder (PGD) is characterized by persistent yearning, intrusive memories, rumination, anger, and guilt, as well as difficulties in accepting the loss, avoidance behaviors, and diminished life meaning (4).

Cognitive-behavioral theory (CBT) explains the development and persistence of PGD symptoms through: (1) Difficulty integrating the loss into autobiographical memory, (2) maladaptive beliefs and interpretations, and (3) avoidance behaviors tied to anxiety and depression (5). Accordingly, CBT-based therapies for PGD target these domains to help individuals process loss, modify negative cognitions, and decrease avoidance, and have shown efficacy (6).

Avoidance behaviors contributing to PGD are divided into depressive avoidance (DA) and anxious avoidance (AA). The DA involves withdrawal from meaningful or enjoyable activities due to a sense of meaninglessness following the loss, while AA involves evading reminders of the deceased out of fear of being overwhelmed (7).

To assess these, Boelen and van den Bout (8) developed the Depressive and Anxious Avoidance in Prolonged Grief Questionnaire (DAAPGQ), comprising nine items (five for DA, four for AA). Original validation indicated that these are distinct constructs, both contributing uniquely to PGD severity after controlling for demographic and loss-related variables. Both subscales were somewhat negatively correlated with time since loss, but the decrease was minimal across time (8).

Subsequent studies underscore the important roles of DA and AA in PGD. For example, AA, especially within the first year of bereavement, increases the risk for PGD, while DA mediates links between depression, PGD, PTSD, and violent losses (7, 9). Moreover, DA is associated with higher PGD and PTSD, whereas AA is related to thoughts of revenge following homicide losses (10). Both avoidance subtypes partially mediate relationships between PGD, rumination, and worry, highlighting the importance of targeting avoidance processes in therapy (11, 12). Treml et al. (13) confirmed the factorial validity and high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha .86 for DA, .95 for AA) of the DAAPGQ in German, further supporting its utility.

Given the centrality of avoidance in PGD’s onset and maintenance, valid measures like the DAAPGQ are critical for research and clinical practice — to identify at-risk individuals, tailor interventions, and monitor change. The inclusion of PGD in ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR reinforces the need for etiological studies on grief-related avoidance and cross-culturally validated assessment tools (14). Cultural differences in expressions and duration of grief necessitate the translation and validation of the DAAPGQ in diverse populations.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to translate and psychometrically evaluate the Persian version of the DAAPGQ. We anticipated replicating the two-factor structure found in the original version and expected positive associations with PGD, depression, anxiety, and grief rumination, as well as a small negative correlation with time since loss.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a cross-sectional study that assessed the psychometric properties of the Iranian DAAPGQ using non-probabilistic snowball and convenience sampling. Eligible participants were bereaved individuals aged 18 or older, recruited via an online survey platform after providing written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included being too overwhelmed by grief to participate or having experienced suicidal thoughts within the past month. According to Hair (15), a minimum sample size of 90 participants was determined, based on the DAAPGQ’s 9 items and a 10:1 participant-to-item ratio, to ensure adequate power for factor analysis and avoid data overfitting.

3.2. Procedure

The research, part of a doctoral dissertation, was ethically approved (IR.USWR.REC.1401.249) by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Data were collected from May to August 2023 through multiple recruitment strategies, including a project webpage, personal contacts, and social media. Participants accessed and completed the online questionnaire via a unique link. To ensure complete data, a forced-response design required participants to answer all questions before submission, resulting in no missing data. Three attention-check questions were included to minimize inattentive responses, and clear instructions emphasized accurate and complete answers. The consent form clarified voluntary participation and confidentiality. Data collection was paused during sensitive periods, such as Nowruz, to prioritize participants’ well-being. To reduce emotional distress, sociodemographic questions appeared at the end of the survey. These steps ensured both data integrity and ethical standards.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Sociodemographic Information Questionnaire

A researcher-made tool collected data on participants’ characteristics (age, gender, marital status), along with information about the deceased (age, sex) and loss circumstances (time since loss, relation to the deceased).

3.3.2. Depressive and Anxious Avoidance in Prolonged Grief Disorder

The DAAPGQ assesses DA and AA related to prolonged grief. This nine-item scale, rated on an eight-point scale (1 = “not at all true” to 8 = “completely true”), includes five items for DA and four for AA. Internal consistency of the DA and AA subscales was previously reported as 0.90 and 0.74, with a correlation of R = 0.77 (8). For this study, after obtaining author permission, the DAAPGQ was translated into Persian using standard forward-back translation, with reconciliation by experts to ensure conceptual equivalence.

3.3.3. Utrecht Grief Rumination Scale

The Utrecht Grief Rumination Scale (UGRS), developed by Eisma et al. (12), measures grief-specific rumination across 15 items, with responses on a five-point scale (1 = “never” to 5 = “very often”). It provides a total score and scores for five subscales: Counterfactuals (α = 0.78), relationship (α = 0.77), injustice (α = 0.73), meaning (α = 0.83), and reactions (α = 0.76). Overall, the UGRS showed high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91, McDonald’s omega 0.92) in the present study.

3.3.4. Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale-13-Revised

The Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale-13-Revised (PG-13-R), developed by Prigerson et al. (4), assesses PGS using 13 Likert-scale items and three gatekeeper questions. The scale yields total scores from 10 to 50 and has shown high internal consistency (α = 0.83 - 0.93), including 0.87 in an Iranian sample (16).

3.3.5. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), developed by Zigmond and Snaith (17), contains 14 items (seven each for anxiety and depression), with scores above 8 on either subscale suggesting possible anxiety or depression. Validation in Iranian samples showed adequate reliability (depression: α = 0.70, anxiety: α = 0.85) and good test-retest correlation (depression: R = 0.77, anxiety: R = 0.81) (18).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26. Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency, standard deviation, kurtosis, and skewness, were calculated for all DAAPGQ items using the complete sample (n = 170), with no missing data due to the online survey’s forced-response design. Construct validity was assessed via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in Mplus 8.3. The analysis followed theoretical and empirical foundations suggesting a two-factor model (DA and AA) for the DAAPGQ (8, 13). The CFA was conducted using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) approach, with latent variable variances fixed to one. Two competing models were evaluated. Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices: A non-significant chi-square (χ2) test, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with recommended thresholds of TLI and CFI greater than 0.90, χ2/df between 2 and 3, and RMSEA less than 0.08 (19). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used for model comparison, with lower values indicating a better fit (20).

Once the best-fitting model was selected, convergent validity was examined via Pearson correlations between DAAPGQ subscales and related constructs (grief rumination, PGD symptoms, anxiety, and depression). Convergent validity was also assessed using average variance extracted (AVE), with a criterion of AVE > 0.50 (21). Discriminant validity was considered adequate when AVE exceeded both maximum shared variance (MSV) and average shared variance (ASV) for each factor (15). Construct validity was further explored via hierarchical regression analysis to test whether DA and AA predicted PGD symptoms after adjusting for demographic and loss-related variables. Scale reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and corrected item-total correlations, with McDonald’s omega as an additional reliability index (22). Values of α and ωt ≥ 0.60 were considered acceptable (23).

4. Results

The study included 170 SLSs, with 55% identifying as male and 44.7% as female. The participants' average age was 39.06 years (SD = 11.24; range: 18 to 68). Their characteristics are as follows in Table 1.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 76 (44.7) |

| Male | 94 (55.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 50 (29.4) |

| Married | 109 (64.1) |

| Divorced | 5 (2.9) |

| Widowed | 6 (3.5) |

| Educational Level | |

| Middle school | 15 (8.8) |

| High school | 43 (25.3) |

| Post graduate diploma | 22 (12.9) |

| Bachelor degree | 65 (38.2) |

| Master degree | 22 (12.9) |

| PhD | 3 (1.8) |

| Time | |

| Less than 6 (mo) | 31 (18.2) |

| 6 - 12 (mo) | 34 (20) |

| 1 - 2 (y) | 20 (11.8) |

| 2 - 3 (y) | 35 (20.6) |

| 3 - 4 (y) | 17 (10) |

| 4 - 5 (y) | 33 (19.4) |

| Degree of kinship | |

| Spouse | 8 (4.7) |

| Child | 33 (19.4) |

| Father | 40 (23.5) |

| Mother | 25 (14.7) |

| Grandparent | 23 (13.5) |

| Sibling | 6 (3.5) |

| Brother | 16 (9.4) |

| Aunt | 6 (3.5) |

| Uncle | 13 (7.6) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and reliability indices for the Persian DAAPGQ. Item 8 showed the highest mean (4.67 ± 2.42), while item 4 had the lowest (2.99 ± 2.43). Item - total correlations ranged from 0.52 to 0.78 (M = 0.66). The mean inter-item correlation was 0.50 (range: 0.31 - 0.81). The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91); DA and AA subscales had α = 0.91 and 0.82, respectively. McDonald’s ω was 0.91 (DA), 0.84 (AA), and 0.91 (total score).

| Items | Mean ± SD | Corrected Item-Total Correlation Ritc | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item is Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.72 ± 2.40 | 0.64 | 0.89 |

| 2 | 3.53 ± 2.38 | 0.75 | 0.89 |

| 3 | 3.16 ± 2.25 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| 4 | 2.99 ± 2.43 | 0.73 | 0.89 |

| 5 | 3.41 ± 2.40 | 0.70 | 0.89 |

| 6 | 3.86 ± 2.70 | 0.59 | 0.90 |

| 7 | 3.72 ± 2.51 | 0.68 | 0.89 |

| 8 | 4.67 ± 2.42 | 0.52 | 0.90 |

| 9 | 4.43 ± 2.37 | 0.63 | 0.89 |

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Depressive and Anxious Avoidance in Prolonged Grief Questionnaire

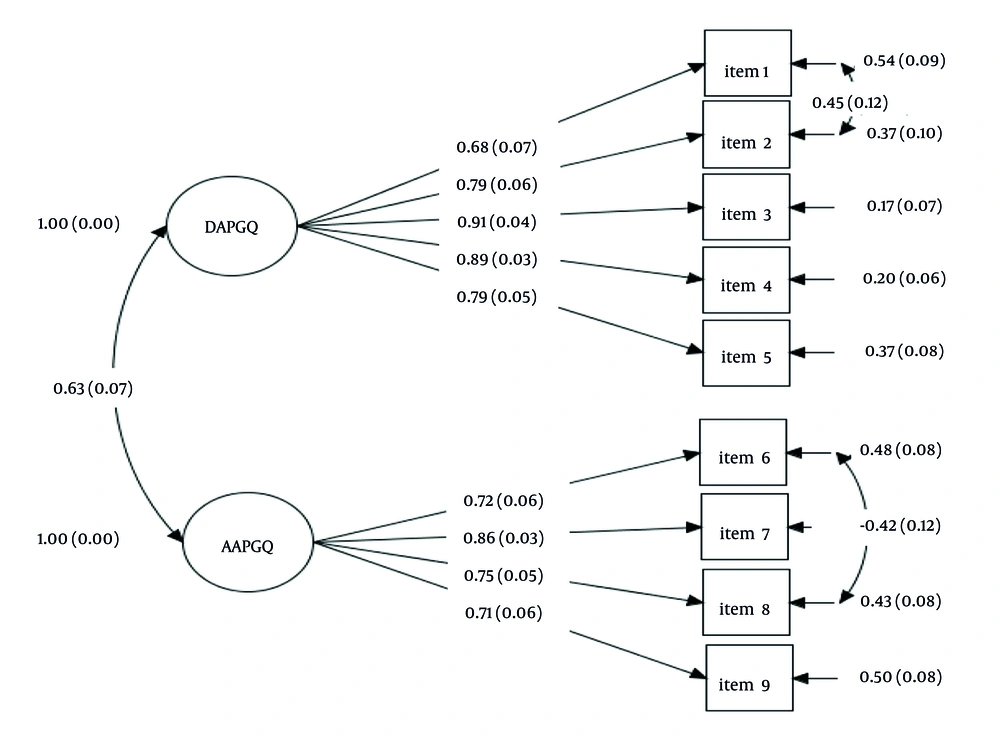

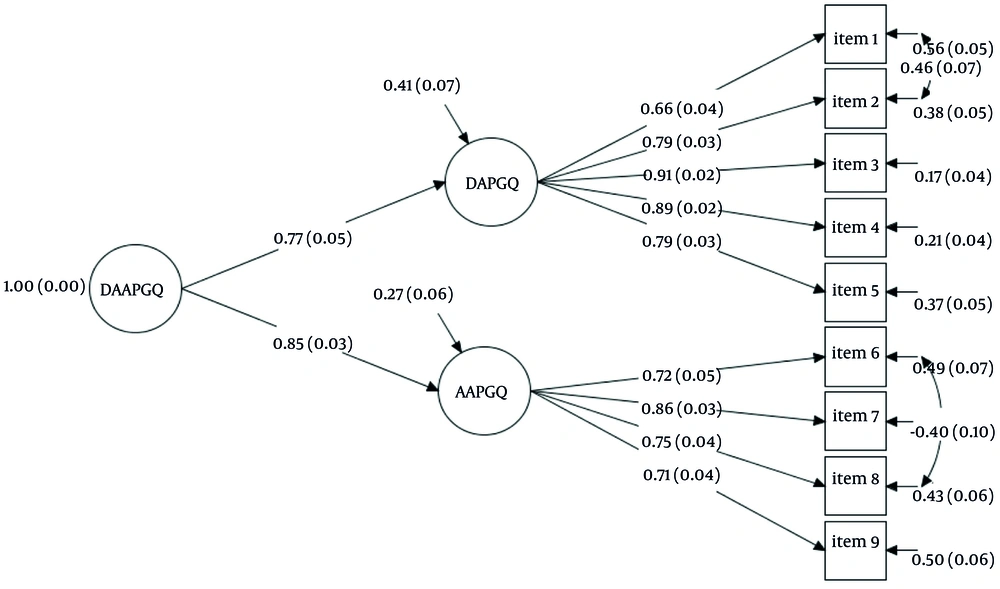

Based on the theoretical framework and previous psychometric research, two models were evaluated using MLE, with their fit indices reported in Table 3. The first model, a correlated two-factor structure (Model 1; Figure 1), showed adequate fit to the data (TLI = 0.910, CFI = 0.940), although the RMSEA was somewhat elevated at 0.089 [90% CI (0.064, 0.124)]. The higher-order factor model (Model 2; Figure 2), in which the two subscales served as indicators for the overarching DAAPGQ construct, displayed good fit indices (TLI = 0.939, CFI = 0.957), with RMSEA = 0.099 [90% CI (0.071, 0.129)]. Both models demonstrated acceptable fit, but Model 2 provided a marginally superior fit according to the AIC criterion. In Model 2, all standardized factor loadings were above 0.50, confirming adequate factorial validity, and all item loadings met local fit criteria (15). The DAAPGQ subscales and total scores correlated highly, with inter-subscale correlations between 0.52 and 0.78 (Table 2). The addition of error covariances between items 1 and 2, and between items 6 and 8, further enhanced fit, reflecting shared variance. Overall, both models confirmed that DA and AA are distinct but related constructs subsumed under a unified avoidance factor.

Abbreviations: TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; χ2, chi-square; GFI, Goodness-of-Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; AIC, Akaike information criterion.

a P < 0.001.

4.3. Convergent and Divergent Validity

According to the convergent validity criterion, both the DA and AA subscales of the DAAPGQ demonstrated an AVE greater than 0.50 (DA = 0.643; AA = 0.527), supporting adequate convergent validity. With respect to divergent validity, the AVE of both subscales was higher than the corresponding MSV and ASV values (MSV = 0.430; ASV = 0.430 for both DA and AA). Therefore, these results indicate that both DA and AA possess satisfactory divergent validity.

4.4. Concurrent Validity

As anticipated, the DAAPGQ subscales showed significant correlations with depression, prolonged grief, anxiety, and grief rumination symptoms, while exhibiting a negative correlation with the time since the loss (Table 4). The strongest positive correlation was observed between the PG-13 and the DA subscale, with a correlation coefficient of R = 0.75 (P < 0.001), while the weakest correlation was found between the AA subscale and the time since loss, with R = -0.28 (P < 0.001). Furthermore, our regression analysis showed that a hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to assess the contributions of demographic variables, loss-related characteristics, and avoidance constructs (DA and AA) to symptoms of PGD (Table 5). In the first step, demographic variables (gender, age, education) were entered, but none were statistically significant (all P > 0.05) and explained minimal variance (R2 = 0.016). In step two, loss-related factors (time since loss, relationship to the deceased) were added, leading to a significant increase in explained variance (ΔR2 = 0.181, P < 0.01; total R2 = 0.197). Only time since loss predicted PGD symptoms (β = -0.427, B = -2.252, SE B = 0.317, P = 0.001), indicating that increased time since loss is associated with lower symptom severity. In the final step, adding DA and AA considerably raised explained variance (ΔR2 = 0.447, P < 0.01; total R2 = 0.664), with both DA (β = 0.504, B = 0.553, SE B = 0.055, P = 0.001) and AA (β = 0.277, B = 0.242, SE B = 0.067, P = 0.001) serving as significant predictors. Time since loss also remained significant (β = -0.172, B = -0.909, SE B = 0.266, P = 0.001).

| Variables a | PGD-13-R | HADS-Anxiety | HADS-Depression | Rumination | Time Since Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive A | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.60 | -0.32 |

| Anxious A | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.45 | -0.28 |

| DAAPGQ total | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.60 | -0.36 |

Abbreviations: PGD, prolonged grief disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; DAAPGQ, Depressive and Anxious Avoidance in Prolonged Grief Questionnaire.

a P < 0.001.

| Variables | B | SE B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.016 | 0.016 | ||||

| Constant | 27.555 | 4.183 | - | - | ||

| Gender | 0.732 | 1.451 | 0.039 | 0.614 | ||

| Age | 0.028 | 0.064 | 0.033 | 0.670 | ||

| Education | -0.795 | 0.577 | -0.108 | 0.170 | ||

| Step2 | 0.197 | 0.181 b | ||||

| Constant | 34.917 | 4.309 | - | - | ||

| Gender | 0.490 | 1.333 | 0.026 | 0.713 | ||

| Age | 0.047 | 0.059 | 0.057 | 0.427 | ||

| Education | -0.695 | 0.526 | -0.094 | 0.188 | ||

| Time since loss | -2.252 | 0.317 | -0.427 | 0.001 | ||

| Relationship to the deceased | -0.091 | 0.297 | -0.022 | 0.758 | ||

| Step 3 | 0.664 | 0.477 b | ||||

| Constant | 19.785 | 3.109 | - | - | ||

| Gender | -0.077 | 0.970 | -0.004 | 0.937 | ||

| Age | -0.043 | 0.894 | 0.021 | 0.655 | ||

| Time since loss | -0.909 | 0.266 | -0.172 | 0.001 | ||

| Relationship to the deceased | -0.035 | 0.199 | -0.008 | 0.860 | ||

| DA | 0.504 | 0.055 | 0.553 | 0.001 | ||

| AA | 0.277 | 0.067 | 0.242 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: DA, depressive avoidance; AA, anxious avoidance.

a B: Unstandardized regression coefficient; β: Standardized coefficient; ΔR2: Change in R2; induced by predictors entered at regression step.

b P < 0.01.

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the DAAPGQ among SLSs in Iran, focusing on reliability and construct validity, as well as convergent, divergent, and concurrent validity. The DAAPGQ subscales and total score demonstrated strong reliability, as indicated by satisfactory item-total and inter-item correlations and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Our findings align with previous research by Boelen and Van Den Bout (8) and Treml et al. (13), where the DA and AA subscales also showed high internal consistency. For instance, Cronbach’s alpha for the DA and AA subscales was 0.91 and 0.82, respectively, comparable to the German validation.

Construct validity was examined using CFA, testing both a higher-order factor model and a correlated two-factor model. Both models demonstrated adequate fit, but the second-order model, with DAAPGQ as a higher-order latent construct, showed a slightly better fit based on lower AIC values, consistent with Boelen and Van Den Bout (8) and Treml et al. (13). To enhance model fit, two error covariances (between items 1 and 2, and items 6 and 8) were added, justified by overlapping content. This supports the conceptual differentiation between DA and AA within the cognitive-behavioral framework for PGD. The convergent validity of the subscales was confirmed, with AVE values above 0.50, and the results also supported the divergent validity, indicating that the two subscales measure related but distinct constructs.

Cultural factors in Iran, including social norms, religious beliefs, and family dynamics, may influence both the manifestation of avoidance behaviors and responses to specific items (24). Stigma around mental health and emotional expression may encourage avoidant strategies or affect item interpretation, which could partially explain the need for correlated errors in the CFA. Results indicated that avoidance tendencies, once established, remain relatively stable over time, as evidenced by only minor decreases in the DA and AA subscales with increasing time since loss (25). Both subscales also showed significant positive correlations with PGD symptoms, grief rumination, anxiety, and depression, aligning with prior theory and research (25, 26). These findings highlight avoidance as a central mechanism sustaining PGD by hindering adaptive emotional processing. In addition, the strong association between avoidance and rumination further supports the role of maladaptive coping strategies, as emphasized in cognitive-behavioral models of prolonged grief (26).

Hierarchical regression analysis confirmed that both DA and AA significantly and independently predicted PGD symptoms, together accounting for 44% of the variance. These results reinforce the role of avoidance as a key maintaining factor in PGD and highlight the clinical importance of addressing avoidance in treatment for bereaved individuals (5). Several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design does not allow causal inferences; therefore, longitudinal studies are needed. The present study did not evaluate test-retest reliability or sensitivity to change (responsiveness) of the DAAPGQ, which should be explored in future research. Additionally, alternative measures for convergent validity, such as the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II, were not included, which may restrict the breadth of validation. Although the PG-13-R, used for PGD symptoms assessment, is widely recognized, it does not fully cover all current diagnostic criteria from the ICD-11 or DSM-5-TR. At the time of data collection, no tool was available that encompassed all ICD-11 criteria. We recommend that future studies use instruments covering the latest standards to increase the accuracy of normative data.

5.1. Conclusions

The DAAPGQ is a psychometrically sound instrument for assessing maladaptive avoidance in bereavement, distinguishing between DA and AA as related but separate mechanisms. These avoidance patterns may obstruct adaptive grieving and contribute to the persistence of PGD symptoms. Clinically, the DAAPGQ enables the identification and differentiation of avoidance forms among SLSs, supporting more targeted treatment planning. Its use can inform tailored interventions, such as exposure-based therapies, CBT, and ACT, enhancing emotional processing and psychological outcomes. Moreover, the DAAPGQ serves as a screening tool in both clinical and community settings, facilitating early identification and intervention for those at risk of PGD. In summary, the DAAPGQ offers clinicians and researchers a reliable and valid measure for the assessment, treatment, and evaluation of interventions in individuals bereaved by suicide, thereby promoting more effective, personalized mental health care.