1. Background

Walton defined working life as employees’ reaction towards their job and satisfying job requirements and mental health (1). Quality of working life (QWL) is a multidimensional construct, which includes concepts such as welfare and health services, incentive plans, job appropriateness, job security, the importance of the role of the individual in the organization, providing growth and development, participation in decision-making, reducing job conflicts and ambiguities, training and rewards systems (2), and is a part of working environment variables and overall assessment of a person about his/her own job (3, 4). Religious coping is a method by which people take advantage of their religious rituals and beliefs to deal with problems and pressures of life (5). Positive religious coping (tendency to religion), which involves a sense of spirituality, relationship with God and spiritual connection with others, has positive consequences such as higher self-esteem, better quality of life, more psychological and spiritual growth in relation with tension, while negative religious coping (rejection of religion) represents less secure relationship with God and pessimistic uncertain view of world that causes negative consequences such as depression, emotional distress, poor physical health and quality of life (6). Researchers believe that religion must be considered in most studies because they expect people with higher level of religious and coping to be happier life and more satisfied with their work (7). Improving the quality of working life in nurses and other staff is one of the most important ways to sustain the health system (8). In every organization, high level of quality of working life is necessary to attract employees. Since working life will affect people’s feeling about their workplace, assessment of quality of working life is essential (9). This issue in hospitals is very important because nurses are the largest group of workers in every hospital around the world (10).

In a study that was conducted on nurses working in military hospitals, the average score for quality of working life for nurses was 66.1 ± 1.6; the quality of working life of 81%, 13% and 6% of nurses was average, weak and high, respectively (11). In a study that was conducted on nurses of Urumieh University of Medical Sciences, 30.9% of nurses had poor quality of life, 67.6% had average and only 1.5% had desirable working life quality (12). According to available databases, there was no study published about religious coping among nurses but in a study that was conducted on students of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, 85.5% of the studied samples gained average scores in using religious coping, 10.4% strongly applied religious coping and 3.8% were poor at using religious coping (13). In a study of hemodialysis patients, mean and standard deviation of the score of positive and negative religious coping strategies were 23.38 ± 4.17 and 11.46 ± 4.34, respectively. About 52.6% of samples had higher than average level of positive religious coping (desirable condition) and the score of negative religious coping was 37.9% (14). Literatures relating to the quality of working life are limited and most research in this area is related to job satisfaction (15).

According to available data-bases, no study was done on the relationship between religious coping and quality of work life of nurses, therefore, this study aimed to determine the relationship between religious coping and quality of life of nurses.

2. Materials and Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was done on nurses of training-therapeutic hospitals in Sari city during year 2015 (two of them were general and others were specialized nurses). Multi-stage sampling was performed for sample collection. After explaining the purpose of the study to nurses, consent forms were obtained. Some of the parameters of the consent form included ensuring non-disclosure of information and exclusion from the study at any time based on request. Inclusion criteria were having at least one-year working experience, full satisfaction with the study and lack of any mental health disorders. Exclusion criteria also included any event preventing continuation of the study of nurses. Multi-stage sampling was done among four educational-therapeutic hospitals, which were branches of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. Among 1140 nurses from these four hospitals (Booali-Sina = 226 nurses, Imam = 404 nurses, Zare = 230 nurses and Fatemeh-Zahra = 280 nurses) based on Krejcie-Morgan table, 285 nurses were recruited, according to the number of nurses per hospital (Booali-Sina = 57, Imam = 101, Zare = 57 and Fateme-Zahra = 70).

2.1. Questionnaire

Religious coping skill of nurses was measured by a standard questionnaire of religious coping. Religious coping deals with aspects of belief and religious practice, which help individuals with understanding of the situation, and supports and allows them to find strategies for religious coping to deal with problems of life. The reliability of the questionnaire was estimated to be r = 0.88 using test-retest method and again proved by performing split half test and Cronbach’s of 0.88 and 0.90, respectively. Finally, after carrying out the necessary reforms under the supervision of professors of Islamic Studies Office in Tehran Psychiatric Institute of Mental Health, the final version was approved. This scale has 31 items (with five options), which are scored on a Likert scale. Mean and standard deviation of scores are ranked in three levels of poor (97 or less), medium (98 - 107) and strong (108 and more) (13, 16). Quality of working life of nurses was assessed by Walton’s questionnaire of quality of working life. This tool deals with adequate and fair payment, safe and healthy workplace, growth opportunities and continuous security, legalism in working organization, social affiliation of working life, social integration in working organization, and providing immediate opportunities for the development and use of human capabilities. This questionnaire includes 32 questions, each question is considered as a component and the answers are scored on a five-point Likert scale. A score of 1 to 5 is allocated to each item. Scores less than 60, 60 to 120, and higher than 120, indicate low, average and high levels of quality of work life. Reliability of the questionnaire was approved by test-re-test method and Cronbach’s alpha at 0.85 and 0.89, respectively (17). Also, a demographic questionnaire with variables of age, gender, marital status, place of residence, number of children, educational level and income adequacy, work experience, current ward, type of employment, working shift and hours of working overtime was designed.

2.2. Data Analysis

Data was analyzed by SPSS 16 software using descriptive (mean and SD) and inferential statistics (Pearson and Spearman correlation). Significance level was considered P < 0.05.

3. Results

Among a total of 285 nurses, 70 were male (24.6%) and 215 were female (75.4%). The average age was 33 (SD = 6.95; 95%CI: 32.19 - 33.81) years, 230 were married (80.7%), 236 had their own apartments (82.8%) and most of them (57.5%) had children. Most of the nurses working in the studied hospitals had Bachelors degree (95.8%) and the average work experience was 8.85 ± 8.033 years. Overall, 109 nurses (38.2%) were officially employed and 87 nurses (30.5%) were contract nurses. Most nurses had circulating working shifts (86.3%) and they had an average income (51.6%). The average overtime working hours was 58.66 ± 45.518 hours per month.

According to Table 1, most of the nurses had high level of religious coping (42.8%) and the level of quality of working life of most nurses (84.2%) was estimated to be average. According to Pearson's correlation, there was a direct and significant relationship between variables of religious coping behaviors and quality of working life of nurses (r = 0.387, P < 0.001). Females had higher levels of religious coping (mean ± SD: 103.24 ± 15.567) when compared to males (mean ± SD: 97.39 ± 19.587) and nurses with appropriate economic status had better quality of working life (indicated in Table 2).

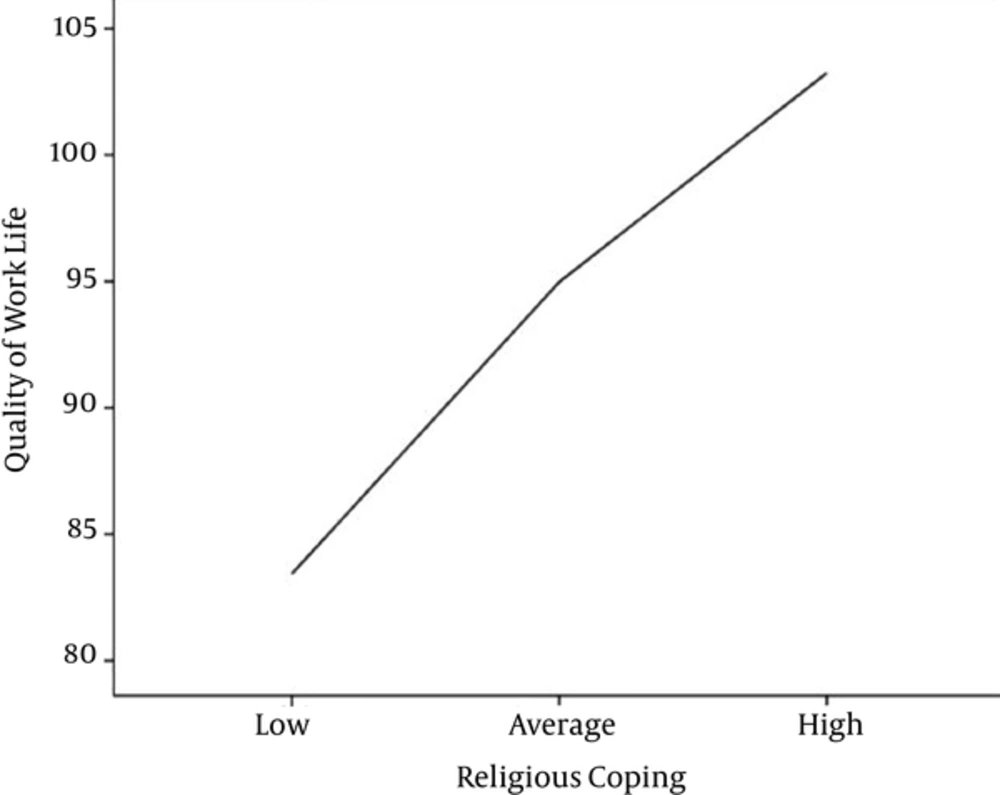

Figure 1 represents a direct and positive relationship between religious coping and quality of working life so that working quality improves by increasing religious coping behaviors.

| Variable | Religious Coping Level | Quality of Working life Level |

|---|---|---|

| Weak | 101 (35.4) | 10 (3.5) |

| Average | 62 (21.8) | 240 (84.2) |

| High | 122 (42.8) | 35 (12.3) |

| Mean (SD) | 101.80 (16.798) | 85.57 (16.769) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

aSignificant at P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In the present study, a direct and positive relationship was found between religious coping behaviors and nurses’ working life quality. In the study of Winkelman et al. religion played an important role in the quality of life of cancer patients (18), which is consistent with the results of the present study. In another study on patients with multiple sclerosis, in line with the findings of the present study, aspects of religious coping had a considerable impact on aspects of quality of life (19). Quality of working life is one of the variables that are of interest to a lot of managers, who seek to improve the quality of their human resources (20). In an international study that was conducted in different countries, 10,400 employees of various organizations were questioned. The most important expectations of these people from their working environment included balance between work and personal life, having an enjoyable job, a sense of security, having suitable income and benefits and good coworkers, and in most countries the item of balance between work and personal life was the most important factor of working life satisfaction (21). Winter et al. noted quality of working life as a factor through which society members learn how to better work together and apply necessary improvements to achieve the goals of quality of life and job simultaneously (22). In another study on patients with coronary artery disease in the city of Tehran, in line with the results of this study, the effects of religious coping methods and quality of life were supported (23). Improving QWL leads to job satisfaction and satisfaction with other aspects of life (24). For example, in a study on practitioner students, a direct relationship was found between religious tendencies and student satisfaction (25). Nurses as one of the largest groups of healthcare providers and have significant potentials, which can affect the quality of health care. It can be said that nursing quality directly affects the efficiency of the health system, therefore their quality of working life is important and can be strengthened by religious coping (26). In the present study, 84.2% of nurses had appropriate QWL. Inconsistent with the findings of the current study, in another study, 31.1% of nurses had moderate QWL (27). Also inconsistent with the present study, most nurses in the hospitals of Tehran Medical Sciences had bad level of QWL (26). Type of hospital and cultural and religious differences, which have a significant impact on QWL, can be the possible cause of this inconsistency. Kibry and Harter reported that employees, who work in small organizations compared with large companies’ staff, have less dissatisfaction with the quality of their work (28). Studies have confirmed that issues of QWL affect employees’ satisfaction and have a role on keeping or leaving their current job, so deficiencies in this area could cause job burnout (29, 30). Different aspects of work difficulty may influence quality of nurses’ performance; higher levels of QWL have a positive effect on work satisfaction and decrease the amount of work difficulty and this issue is very important (31). This finding was approved by many studies (32, 33). In the present study, a direct and significant relationship was found between age and nurses’ QWL. In line with this finding, in a study by Smith in the United States of America, it was shown that the amount of income and autonomy at work are important elements in improving QWL. However, not clearly defined organizational policies and job stress play a role in nurses’ dissatisfaction (34). Littler also showed that some elements such as payment reduction and no clear job prospects contribute to dissatisfaction of nurses with quality of their working lives (35). In this study, most of the nurses (42.8%) had high levels of religious coping while in the study of Khazayi et al. only 4% of the studied students had high religious coping tendencies (36). Also in the study of Omrannasab, the amount of average and strong religious beliefs was announced to be 57.3% and 19.5%, respectively (37). The results of Azmi’s study also showed that 85.8% of students strongly used religious coping, 10.4% used this coping strategy on an average level and 3.8% were weak (38). In addition to the possible role of culture and age, the study’s population was also one of the probable differences between the above- mentioned and the present study.

Finally, the results showed a significant association between religious coping and quality of working life of nurses, which suggests that by making efforts to improve the quality of religious coping among this group by frequent training sessions, we can improve their quality of working life. Nurses are the largest group of health care providers in the health system and they must have desirable working lives in order to provide better care for the patients. It is hoped that with the strengthening of positive religious coping, one can take a step towards improving the quality working life for nurses. Limitations of this study included items, such as lack of similar studies on nursing religious coping behaviors (which was due to the novelty of this article) and also significant difference in number of males and females. In this regard, it is recommended that similar studies be carried out on broader communities.