1. Context

Childbirth is regarded as a stressful and exciting event for parents (1). This sense of excitement does stay for a short time and will soon be substituted for anxiety when the infant is born prematurely (2). For parents who have been waiting for a long time to have a healthy infant, unexpected birth of a premature infant is a daunting experience (3). Uncertainty increases parents’ tension (4). Deprivation of the expected parental role is challenging (5). They have to deal with stressful conditions of their infants hospitalized in the strange environment of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for an uncertain amount of time depending on the intensity of disease and prematurity (6). These stressful conditions involve parents in a crisis, which can only be overcome under a comprehensive support. People differ in how much support they need under stressful conditions and the fulfillment of their needs determines their satisfaction with the received support (2). Moreover, the health of infants and parents depends on the satisfaction of parents’ needs (7); therefore, it is important to become familiar with these needs.

Studies have shown that parents’ experiences of premature birth are context base and thus, their reaction depends on cultural contexts, beliefs, and opinions of their community.

2. Objective

Given the context base nature of the phenomenon and increasing amount of parents living with premature infants (8), this Meta-synthesis was conducted to understand the needs of Iranian parents with premature infants through their experiences in order to promote family-centered care. This is a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies (9-24) conducted in Iran on parents of premature infants.

3. Data Sources

This study is a meta-synthesis study. Meta-synthesis includes the collection of a group of qualitative studies, analysis of their findings, discovery of their essential points, as well as combining and converting them into a more general alternative. Meta-synthesis is as important as it provides a deeper understanding of the investigated phenomenon, aligns the care and decisions with scientific evidence, and also facilitates the use of qualitative research in health sciences.

The seven-staged Noblit and Hare’s (1988) meta-synthesis method has been used in this study (25).

1- The first stage is finding a meta-synthesis-worthy topic for the study within the researcher’s expertise.

2- The selection of illegible studies for meta-synthesis is based on the inclusion criteria.

3- The selected studies are carefully read and re-read to determine their key concepts and themes. In this stage, the researcher should highly consider the details of each of the selected studies.

4- The relationship between studies is investigated. Studies can be regarded as a bilateral translation of each other, contradictory, or somewhat similar to one another. The relationship between studies is determined by extracting key concepts of each of the studies and putting them together.

5- At this stage, studies are translated, or in other words, their key concepts are converted to each other. In the translation process, key concepts of each study are compared with key concepts of the other studies and are then included in meta-synthesis.

6- The end process is creation of a whole from the initial studies, which presents an interpretation of the given phenomenon beyond each of the studies, while encompassing them.

7- The study results will be published.

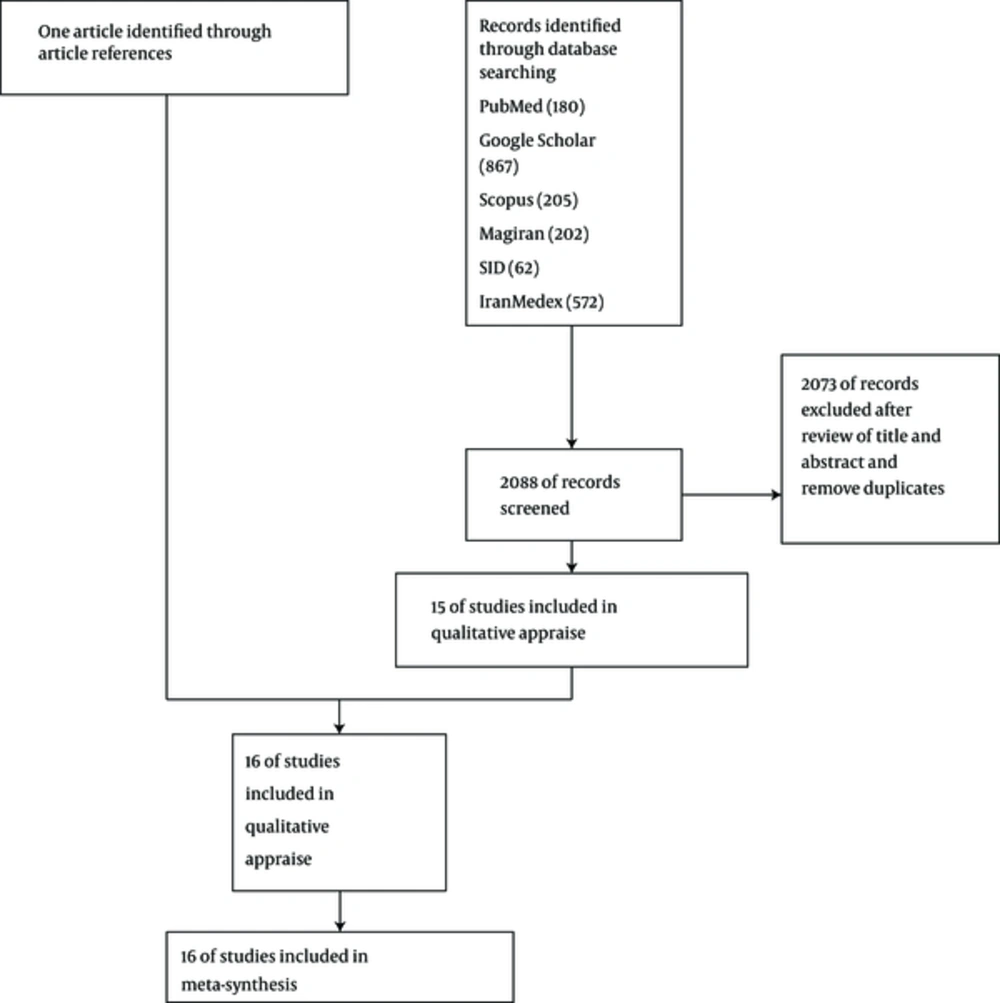

Studies included in this meta-synthesis were obtained by searching Iranian databases namely Iran Medex, Magiran, and SID, as well as international databases namely PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar by 2 independent researchers. Since the domestic databases are not sensitive to search operators (AND, OR, NOT), they were explored using the keyword “premature infant” to develop high sensitivity. In terms of international databases, general keywords (i.e. premature infant, affiliation with Iran) were explored (Figure 1).

The reviewed documents were selected from Farsi and English articles submitted in domestic and international databases before April 12, 2015, with no time limit. In addition, the reference lists of selected articles were screened to find the relevant studies.

4. Study Selection

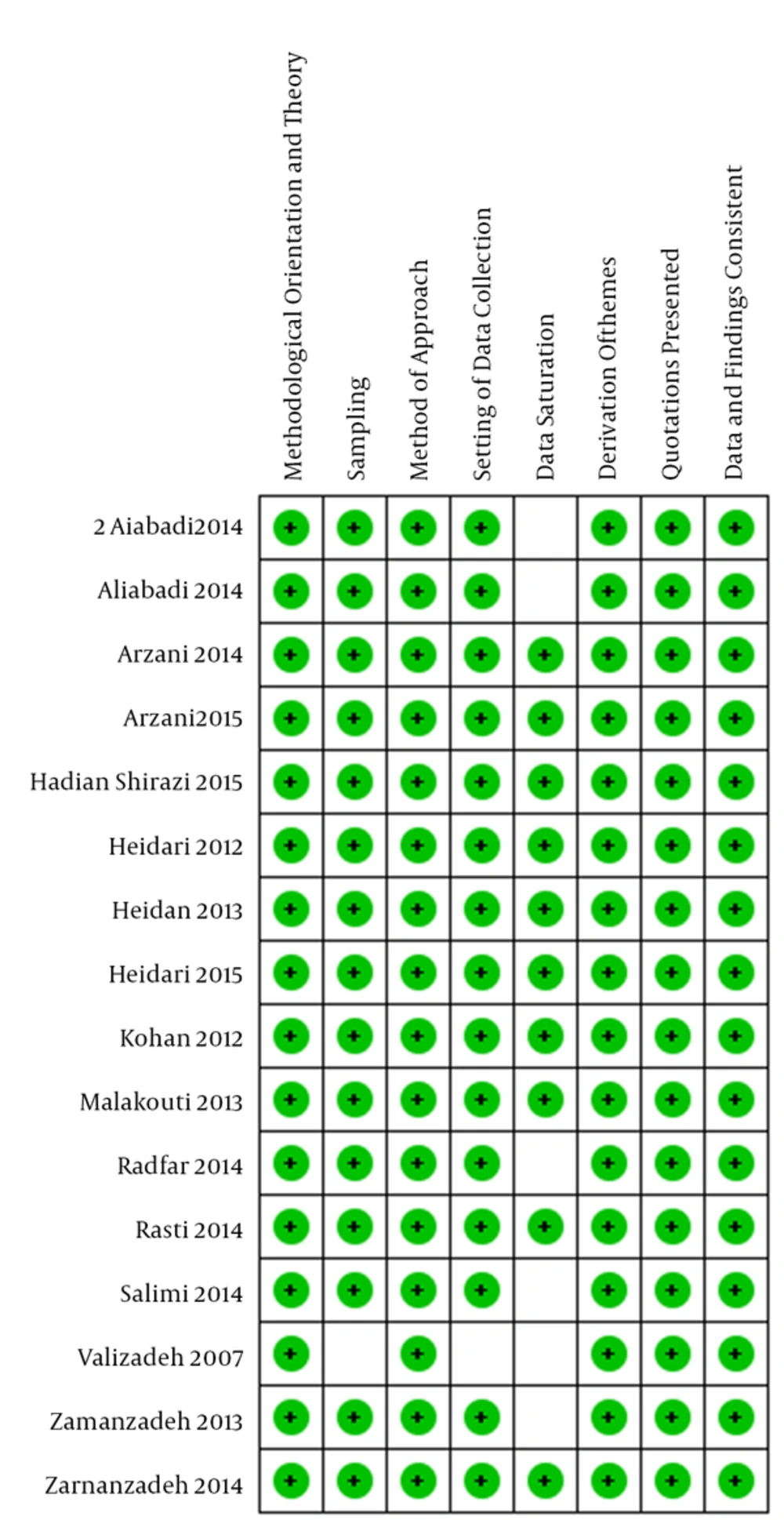

The inclusion criteria for this study included the qualitative studies conducted in Iran on parents with premature infants. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) were used to assess the quality of articles by 2 authors (Seyedeh Saeedeh Mousavi and Afsaneh Keramat) (Figure 2) (26).

5. Data Extraction

A total of 2088 articles were reviewed and evaluated for inclusion based on their focus and methodological comparability of the findings. Studies were excluded if 1, they were not qualitative and 2, have not focused on the experiences of parents of premature infant in Iran.

In addition, the reference lists of selected articles were screened to find the relevant studies.

The final sample included 16 qualitative studies: 2 phenomenological studies, 13 individual in-depth interviews and content analysis studies, and 1 focus group analysis study. Overall, comments of 159 mothers and 18 fathers with premature infants, 14 mothers and 12 fathers with NICU infants, and 12 doctors and 21 nurses of NICU were used (Table 1).

| Study | Sample and Context | Qualitative Analysis Method | Design/Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heidari 2012 | 6 fathers, 7 mothers who have admitted a premature infant in the NICU within the past 24 hours, 5 nurses and 3 physicians who specialized in neonatology, Isfahan | Semi- structured in-depth interviews / inductive approach and content analysis | To explore experiences of Iranian parents with a hospitalized premature infant in NICU and examine socio- cultural factors associated with having a less than perfect infant |

| Arzani 2014 | 15 mothers of infants born prematurely during 2012 - 2013, in medical educational centers in the North and Northwest of Iran | Semi- structured and in-depth interviews/ qualitative content analysis | To explain the experiences of mothers of caring for prematurely born infants |

| Heidari 2013 | 6 fathers, 7 mothers who have admitted a premature infant in the NICU within the past 24 hours, 5 nurses and 3 physicians who specialized in neonatology, Isfahan | Semi- structured in-depth interviews / inductive approach and content analysis | To addresses parental experiences with the infant care in NICU, explore their concerns regarding nursing supports for parents and offer nurses, perspectives on performing duties |

| Kohan 2012 | 10 mothers with premature infants who were hospitalized in the NICU of Afzalipoor hospital in Kerman for at least 1 week | Semi structured interview/content analysis | To explain the experience of mothers with premature infants hospitalized in the NICU |

| Zamanzadeh 2014 | 15 mothers of infants born prematurely during 2012 - 2013, in medical educational centers in the North and Northwest of Iran | Semi- structured and in-depth interviews/ qualitative content analysis | To describe the mothers, experiences of premature birth |

| Zamanzadeh 2013 | 16 mothers who had premature infants who were hospitalized in Iranian NICUs | Deep interviews/content analysis | To examine mothers, experiences of the preparation of their infants for discharge in the Iranian neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) culture |

| Rasti 2014 | 9 parents of premature infants in NICU, 2 nurses, and 1 physician in Akbarabadi, Aliasghar, Firoozgar hospitals in Tehran | Semi structured interview/ content analysis | To specify the educational needs of parents of premature infants admitted in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) |

| Aliabadi 2014 | 9 parents of premature infants in NICU, 2 nurses and 1 physician in Akbarabadi, aliasghar, Firoozgar hospitals in Tehran | Semi structured interview/ content analysis | To compile the supporting- emotional needs of Iranian parents who have a premature infant admitted in NICU |

| Aliabadi 2014 | 9 parents of premature infants in the NICU, 2 nurses, and 1 physician in Akbarabadi, Aliasghar, Firoozgar hospitals in Tehran | Semi structured interview/ content analysis | To understand the confront strategies of parents of premature infants hospitalized in NICU |

| Arzani 2015 | 18 mothers who had a prematurely born infant during 2012 - 2013 in teaching hospitals of the north and northwest of Iran | Semi- structured and in-depth interviews/content analysis | To explore the mothers, strategies regarding prematurely born infant |

| Heidari 2015 | 21 parents, doctors, and nurses in Isfahan hospitals | Qualitative content analysis | To understand the system of parental support in the neonatal intensive care unit |

| Radfar 2014 | 18 mothers of premature and VLBW infants in Shahid Motahari hospital in Orumiyeh, Azarbayjan- e Gharbi | Observe and interview/qualitative content analysis | To explore the women’s experiences of barriers of parenting and coping strategies when their premature infants were born with a very- low- birth- weight |

| Malakouti 2013 | 20 mothers with experience of a premature infant in the intensive care unit of treatment- educational centers of children and Alzahra(s) of Tabriz | semi- structured interviews/phenomenology | Understanding the experiences of mothers in order to provide supports for mothers and improve the quality of nursing care of premature infants and their parents |

| Valizadeh 2007 | 6 mothers of premature infants Referring to Health centers in Tabriz | Deep interviews/phenomenology | To describe, experiences of mothers of premature infants |

| Salimi 2014 | 12 mothers having premature neonates in the NICU of a training hospital in Yazd city | Focus group discussion/ conventional interpretation approach introduced by Dicklman method | To determine the experiences of mothers having premature neonates concerning Kangaroo care |

| Hadian Shirazi 2015 | 7 mothers with premature infants admitted to the NICU of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences | Semi-structured interviews/content analysis | To assess the experience of holy Quran recitation in mothers of premature infants admitted to NICU |

The seven-staged Noblit and Hare’s (1988) meta-synthesis method was used in this study. These stages were followed as carefully and accurately as possible by authors. The selected studies are carefully read and re-read to determine their key concepts and themes. The relationship between studies is investigated. The studies were set against each other since they represented the different perspectives of parents and caregivers. Two authors (Seyedeh Saeedeh Mousavi and Afsaneh Keramat) worked separately to follow Noblit and Hare’s (1988) analysis process of “translating the studies into one another” and subsequently discussed their different understandings.

The authors found that the studies were analogous and could be analyzed as reciprocal. Finally, they agreed on an overarching metaphor that was constructed based on the developed themes and sub themes. In line with interpretation, the researchers provided a coherent description and explanation of the study phenomenon by connecting the findings of their individual research reports to create one meta-finding. Meta-synthesis can be criticized for removing the original studies’ findings and stripping them of their contexts. However, the validity of this meta-synthesis rests in its interpretive logic, where the findings of the research reports were reframed and exhibited in the final product of the study (27). This process provided an audit trail for readers by describing the analysis process in detail, by conducting a thorough literature search, and by precisely appraising the reviewed articles (28, 29).

6. Results

During the analysis phase and determination of the relationship between studies, the meta-synthesis presented 5 related metaphors resulting from 13 categories and 78 integrated codes (Table 2). The metaphors indicated the needs of parents with premature infants as emotional, informational, and communicational, instrumental, appraisal, and spiritual supports. These needs, in many cases, overlap and there are no strong controversies between them. In most cases, these needs overlapped with blur boundaries.

| Theme | Category | Integrated Code |

|---|---|---|

| The need for emotional support | Cultural challenges of Parental role | Excuses of implementation of certain cultural rituals (14, 16) |

| Admiring the ideal form of anything and humiliating any non-ideal thing (10) | ||

| Relatives’ sarcasm when meeting with parents and the infant (10) | ||

| Social stigma of premature birth (10, 19) | ||

| Preferences based on the spouses’ gender (14, 19) | ||

| The society’s judgment on premature birth as an atonement for sin or punishment for wrong deeds (10) | ||

| Blaming the parents for premature birth (19) | ||

| Improper context of parents’ marriage (19) | ||

| Parents’ mental stress vs. their growth | Feeling of alienation (11, 23) | |

| Stress, anxiety, and restlessness (11, 12, 14) | ||

| Fear (11, 12) | ||

| Sense of guilt (10, 11) | ||

| Sadness, despair, and helplessness (10, 11, 14, 16, 18, 19, 23, 24) | ||

| Reduction of mother’s tolerance and showing anger in improper cases (14, 16) | ||

| Shame of social stigma (10, 19) | ||

| Feelings of having no control over their lives and their infant’s lives (10, 18) | ||

| Restriction in life (16, 19) | ||

| Unpredictability of infant’s state (23) | ||

| Comprehensive crisis caused by the unexpected birth of an infant (10, 15, 23) | ||

| Improvement of mother’s physical and mental condition along with the infant’s growth (11, 16) | ||

| Mother getting energy from her infant (16, 22) | ||

| Changes in perception (16) | ||

| Compatibility with parental role and balancing the infant’s needs with parents’ needs (11, 15, 18) | ||

| Enhancing patience and perseverance in oneself (18) | ||

| Inducing positive thoughts and ideas and focus on the positive aspects (18) | ||

| Mental stress stimuli | The critical situation of infant hospitalization in the NICU (9-11, 13, 14, 23) | |

| Feeling responsible for the infant’s pain (11, 14) | ||

| Separation from the infant (11, 13-15, 23) | ||

| Conditions, features, and care needs and therapeutic procedures and the infant’s prognosis (10-12, 14-16, 20, 23, 24) | ||

| The physical and personnel environment around the infant (12, 14, 15, 20, 22) | ||

| The actions and reactions of spouse and relatives (10, 16, 19, 22, 24) | ||

| Personal characteristics of parents (20, 24) | ||

| Mothers’ stress of low milk (10, 12, 19) | ||

| Need for instrumental support | Economic challenges of parental role | Fear of the premature birth costs (10, 13, 14, 19, 24) |

| Fear of losing job and reduction of income as a result of new responsibilities (10) | ||

| Having to be at workplace for living as well as some other places (10, 13) | ||

| Lack of support from insurance organizations (19) | ||

| Lack of economic preparation for crisis of premature birth (10, 15, 23) | ||

| Physical irritation | Power loss caused by care burden (9, 10, 16) | |

| Need for labor recovery is the reason for the inability of most mothers to do all the work related to them and their infant (9, 10, 16) | ||

| Disturbance of parents’ sleep and resting (12, 14, 16, 23) | ||

| Parents’ transportation (13) | ||

| Mothers’ selflessly care of infant (11, 13, 16, 23) | ||

| The need for family-centered care | Disconnection of family function and chain following role changes (10, 13, 23) | |

| Challenging family dynamics following the separation sequence (13) | ||

| Emphasis on continuity of care from the hospital to the community (13) | ||

| The need for policy-making on the constant presence of parents in the NICU | Need for privacy and the minimum lodge in the hospital (11, 19, 22) | |

| Concerns about the lack of care of infant during their absence (12, 13, 23) | ||

| Separation of parents from the infant as a major source of stress and the need to reduce the impact of separation period (9, 11, 13-15, 23) | ||

| Parents’ tendency to spend most of their time with the infant and interact with them (9, 11, 13, 23) | ||

| Interaction with infant, soothing the parents’ physical, and psychological pains (22) | ||

| Attachment process disorder due to the separation of mother from the infant (9, 11, 13, 23) | ||

| Need for spiritual support | Spiritual prosperity vs. spiritual self-alienation | Physical and mental pain relief (21) |

| Regression to spiritual values(21) | ||

| Spiritual growth and excellence during the premature infants care vs. spiritual loss (16, 18, 21) | ||

| Entering a new phase of growth, wisdom and spirituality over the infant’s prematurity vs. spiritual loss (16, 18, 21) | ||

| Spiritual self-carevs. spiritual self-harm | Relying on God, supplication, recourse to Ma’sumun (The Fourteen Infallibles), adherence to the Koran, and surrendered to divine fate (18, 21) | |

| Gratitude to Almighty and grace of God vs. complaining to God (18) | ||

| Submission to God’s will vs. blasphemy (16, 18, 21) | ||

| Premature infant, a sign of divine mercy or test vs. a signs of divine punishment (9-11, 16, 18) | ||

| Need for appraisal support | The efforts to meet parental role | Feeling unable to play parental role (10, 23) |

| Deprivation of unique sense of motherhood (11, 23) | ||

| Guided participation in infant care | Inexperience in premature infant care (11, 12, 14, 23) | |

| Lack of control over the infant’s situation due to lack of participation in the infant care (11, 23) | ||

| Decrease of parental anxiety by treating parents as a part of the care team (14) | ||

| Urgent demand for infant discharge; empowerment training (12, 18) | ||

| Need for informational and communicational support | Parent information challenges | Deprivation of information while needing it (9, 11, 12, 19, 23) |

| Premature infants’ special care features (13, 18) | ||

| Need to learn from multiple reliable sources (12) | ||

| Lack of understanding of the premature infants’ situation (10, 15, 23, 24) | ||

| Unknown prognosis (10, 11, 14) | ||

| Unfamiliarity with the environment (11, 12, 14, 23) | ||

| Lack of knowledge about diagnostic and therapeutic techniques used (14) | ||

| Mothers’ stress of low milk (10) | ||

| Communicational- Informational supports | Searching for support from various sources (9) | |

| Searching for information-communication support from health team (9, 12, 14, 15, 23, 24) | ||

| Need to share the experiences with mothers in similar situation (9, 23) | ||

| Searching for information support from other important relatives (spouse, family, etc.) (9, 13, 23, 24) |

6.1. Need for Emotional Support

Infant hospitalization in the NICU, as a critical situation, evokes negative feelings in parents, which stay with them for long time and sometimes for years. Ignoring those feelings sinks the parents deep in the swamp of a crisis. In contrast, emotional support can heal the injury and save parents’ energy to face with problems strongly and care for their infants (9).

The theme of need for emotional support is extracted from 3 categories of cultural challenges of parental role, parental development versus psychological stress, and psychological stress stimuli.

Haidari and Radfar discussed the social stigma of premature birth that evokes a sense of shame, frustration and self-blame in parents. They added, facing these disappointing reactions may make parents to neglect their infants or hide them from others (10, 19, 20). As explained in Heidari studies, in Iran, which is a family-oriented country, close relationships between relatives sometimes paves the way for pointless meddling and biting sarcasms that blame parents for such a situation or consider it as the “atonement for parents’ sins.”

From the moment they walk in, someone would say “whose heart did you break to get such a punishment?” Or they say, “what sin have you committed in your life to be punished like this?” (10).

The emotional pressure of such negative statements will be inflated further when the context of marriage is not recognized by the community and/or the infant’s gender does not fit a partner’s preferences (10, 14, 19).

Several qualitative studies show that parents suffer from uncomfortable feelings such as alienation with the infant and NICU environment, stress, anxiety, restlessness, guilt, grief, despair, and helplessness (10-12, 14, 16, 18, 19, 24). The first contact with the newborn is filled with fear of his/her death, additional hospitalization problems, and caring for him/her, and a permanent fear induced by technological environment of NICU, as their everlasting nightmare. They lose control of their life and find themselves overwhelmed by the turbulent sea of uncertainties (10-12). Those ashamed of the stigma of premature birth may not tolerate relatives’ hard looks and get isolated, nervous and irritable, and show their irritation at improper situations, thus, leading to self-harm or even child abandonment. While the unexpected birth of an infant and unpredictable nature of his condition, engage the family in an all-round crisis (10, 15, 16, 19, 23).

As Malakouti suggests in his study, fortunately, Iranian devoted parents gradually overcome their initial fear and get along with their parental role by having part in caring for their infant (11). In the shadow of emotional interactions, they make a strong connection with the infant, their physical and psychological state improves in line with the infant growth, and they reach increased mental ability with the infant’s smiling and behavioral reactions (16, 22). Arzani revealed that the idea of an infants’ need for strong caring parents makes them try to get physically, mentally, and emotionally stronger. They try to focus on the positive aspects as the heart of their activities by “looking logically, rather than emotionally, at their situation,” and improving their patience and dedicating positive thoughts. Those who regard premature birth as a flip to realize the power of God, look at life differently, as if they have arrived at a different understanding of life, while others, deal with problems and relationship with God (16).

Several qualitative studies showed that the crisis of premature birth is followed by a turbulent sea of parental emotions (9-11, 13, 14, 23). Those who consider themselves responsible for the infant’s pain suffer from a strong feeling of guilt (11, 14).

“I blamed myself why I did this to my child. Because I worked hard, my amniotic sac was broken and it caused preterm delivery that now I’m regretful for that” (14).

Conditions and attributes, care needs, medical procedures, as well as prognosis of infant, are each a daunting crisis, which is intensified by the physical and personnel environment of the newborn infant (10-12, 14-16, 23). Zamanzadeh reported that the stressful environment of NICU is sometimes to the extent that the parents urge for early discharge. Facing some problems such as an inadequate number of personnel and overloaded shifts increase parental concerns (13). Unpleasant reactions from the partner and relatives, critical looks, and sarcastic remarks make the parents tense up (10, 16, 19, 22). The study of Valizadeh and Radfar showed that parental demographic characteristics such as young age of mother and lack of previous experience, as stressful factors, could make the situation more complicated (20).

6.2. Need for Instrumental Support

Instrumental support includes any type of activity for improving the quality of physical or mental care for the newborn and parents. The instrumental support theme has been extracted from 4 categories, namely economic challenges of parental role, physical irritation, the need for family-oriented care, and the need for a policy on continued presence of parents in NICU.

There are some difficulties that challenge the role of parents, especially fathers: the terrible costs imposed on a family from a premature birth and transportation (due to the lack of facility for mothers to stay at the hospital), fear of losing their job or reduced income as a result of new responsibilities, the need for a fathers’ presence in a workplace to earn the family’s living, in other places such as at home with other children playing the role of a mother or at a hospital supplying the infant’s medical needs, most importantly, expression of emotional support for the mother; and, in general, protection of the family’s integrity (10, 13-15, 19, 24).

A 43-year-old physician with 4 years of experience in NICU said: “He says I cannot sleep at night or during the days’ and this means his problems are not just the infant’s condition, there are other things involved” (14).

In Iranian mothers’ experiences explained in the studies of Heidari and Kohan, receiving the spouse’s support takes the highest priority, while husband’s working and livelihood engagements prevents him from providing enough support to the mother (10, 23).

Mothers suffer from health problems caused by childbirth, inadequate rest during postpartum recovery period, as well as stress and fatigue from the noise of the NICU equipment and environment. Fatigue and the need for labor recovery weaken mothers more in dealing with maternal and daily affairs (14-16, 23). Findings of Malakouti, Kohan, Zamanzadeh, and Arzani showed that the main burden of caring for newborn is on the mother’s shoulders, which reduces her strength gradually along with her untiring and selfless effort (13, 14, 16, 23). In addition, fatigue and risks of transportation are worth mentioning (13).

The study of Heidari, Kohan, and Zamanzadeh suggested that premature birth and its care requirements, mandatory changes in parental role, and separation from routine life deteriorate family structure and make a distance between family members (10, 13, 23).

Obviously, the perception of providing the newborn with a skillful care reduces parental stress and negative feelings, especially in their absence. However, unfortunately, the sense of uncertainty and concern on lack of sufficient caring for their newborns is widely common among Iranian parents, especially in their absence to the extent that they may ask for early hospital discharge. The traces of this type of anxiety could be found in the studies of Malakouti, Kohan, and Zamanzadeh (11-13, 23).

6.3. Need for Spiritual Support

Supporting an individual’s spiritual values is a step to protect his/her integrity, which provides him/her with a spiritual endurance in facing with problems. This kind of support in cultural and religious contexts of Iran is associated with additional blessings.

The theme of the need for spiritual support has been extracted from 2 categories of spiritual prosperity vs. spiritual alienation, and spiritual self-care vs. spiritual self-harm.

In his study, Hadian reported that many parents found relief, peace, strength, and hope in spirituality and trust in God, as the powerful source of support (21). In transition from the issue of premature birth and during the process of taking care of the newborn, they experience new degrees of maturity, wisdom, and spirituality as well as make a greater thriving return to spiritual values (16, 18, 21, 24). Yet, as observed in the study of Arzani, this semantic system may be challenged under the crisis, undermining the individual’s spiritual beliefs (18).

Mother said: “First, I was complaining. I always told God why you should give me this infant. For a moment, I even swore” (18).

Hadian and Arzani discussed the experiences of the parents who regarded premature birth as a sign of divine test and blessings, tried to find happiness and peace under the shadow of trust in God, supplication, recourse to Ma’sumun (The Fourteen Infallibles), adherence to the Koran, and surrendered to divine fate. They felt obligated to pass this divine test perfectly via thanksgiving and striving harder (16, 18, 21).

6.4. Need for Appraisal Support

Empowerment of parents’ ability in playing their role is the most important step to release them from uncertainty in their roles and to return their actual role to them.

The theme of the need for appraisal support results from 2 categories, namely the guided participation in caring for the infant and the efforts to meet parental role.

I think when a person hugs her baby and milk him/her, she thinks that she is really a mother (14).

From the nurses, perspective, even the partial participation of mothers in caring infants in the hospital, helps them to have an active role and less stress at discharge time (18).

Several studies approved parents’ negative emotions due to deprivation from having the unique sense of parentless, sense of ineffectiveness in infant’s fate, and inability in playing parental role (10-12, 14, 15, 18, 23).

6.5. Need for Informational-Communicational Support

Informational deprivation is a biting feeling that challenges the role of a parent and the effort to inform parents is a positive step in restoring a sense of parental control on the newborn infant’s status. Obviously, it is not possible to utilize information unless in the light of contextualizing positive and effective communications, especially with the health team.

The theme of the need for informational-communicational support is extracted from 2 categories, namely informational challenges of parents and informational-communicational supports.

Studies of Malakouti, Heidari, and Rasti suggest that parents of premature infants tend to acquire real, comprehensive and up-to-date information on the infant’s condition, current and future problems, neonatal changes, medicines, diagnostic and treatment procedures, recovery time, as well as possible consequences of prematurity and preventive solutions (11, 14, 15).

“The physicians express contradictory statements regarding my baby’s health status which will cause my stress” (14).

Some experiences of Iranian parents indicate that their feelings of fear and anxiety was due to unresponsiveness of the medical team to parents’ questions and a sense of deprivation induced from inaccessibility to enough neonatal information, concerns caused from the strangeness of environment and equipment, the reason for the use of equipment, the newborn infant's appearance, his/her health condition, and prognosis as well as therapeutic procedures. Failure in gaining access to information and discovering the truth, especially via telephone, when the distance impedes physical presence at hospital irritate parents (9, 11, 12, 14, 19, 23). Kohan and Heydari reported that this multilateral stress caused parent’s to have ongoing health checks of their infants, whose lack of knowledge leaves them with the feeling of incapability on making decisions for their infant and ineffectiveness in his/her destiny (14, 23). They regard this lack of knowledge regarding the infant’s care as an obstacle for cooperation with the medical team. Moreover, Kohan, Zamanzadeh, and Rasti, in their studies, put the failure in satisfying training needs of parents, problem from contradictory training and insufficient leaflets and written information in NICU, as well as the lack of coordination in the discharge process in the NICU (12, 15, 23).

In addition, studies of Aliabadi and Kohan showed that mothers regard mothers of the other hospitalized newborns as the most important source of information (9, 23). Zamanzadeh and Malakouti reported that nurses refuse to give any information on the prediction of disease progression and the parents also prefer to leave it to the doctors (11, 12). In the study of Zamanzadeh, mothers admitted to feel more empowered after receiving breastfeeding and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) training and tried to learn caregiving techniques from different sources. They regarded sharing an experience with peer mothers as a great help in coping with the issue of having a premature infant, accepting his/her conditions, and learning stress coping skills (12).

7. Discussion

This study was done in form of a meta-synthesis comprised of 16 dispersed studies conducted into the experiences of Iranian parents with premature infants, using Nolbit and Hare method (1988). This meta-synthesis provided a larger picture of the experiences of these parents, which can be the basis for an evidence-based function with a more powerful generalizability. Limitation of this study was its different methodology, which was sometimes used in some studies, and to authors, the usefulness of combination of available qualitative studies on the experiences of parents with premature infants affected this limitation.

According to the meta-synthesis, parents in crisis of premature infants essentially needed to be supported so much that they seek support from various sources and even alternatives. Iranian mothers referred to their husband, elderly mothers, medical staff, family members, and God as the most important support source (9). To recognize the nature of support, the meta-synthesis of these experiences includes the need for emotional, instrumental, spiritual, appraisal, and informational support.

7.1. Need for Emotional Support

Emotional support includes listening to parental feelings and concerns, showing concern about their health along with the infant’s health, taking practical measures to care for them and adapt them with an infant’s illness and the other affected aspects of life (30).

The meta-synthesis of Iranian parents’ experience indicates diverse forms of mental tensions in different fields. Just like all parents in other parts of the world, as Lindberg showed in a study, they regard premature birth as a daunting onset of an all-round crisis - a crisis which put them in shock of crushed dreams, leaving them with heavy load of grief, despair, helpless, and anxiety (31). Meanwhile, some social links with friends and family are also annoying. The quality of social bands is affected, by not only interpersonal interactions, but also cultural context. This quality, in turn, affects parental feelings and role (32). On the other hand, many parents of premature infants admit the positive and supportive role of relatives in facing with problems more strongly, organizing familial performance and solving the crisis. As mentioned in the study of Firsman (33), many parents admit their feeling of shame and guilt followed by the intervening and annoying comments of some relatives and even the partner. It seems useful to hold briefing sessions by doctors and nurses in this area for family members to inform them of the newborn infant’s conditions and prevent social stigma associated with premature birth.

In medical environments, health team’s commitment to have an open relationship with parents and their efforts to approach them to reduce anxiety should be exhibited by observing practical standards; in addition, training medical personnel in building a positive and effective relationship to support the provision of family-centered care should be set as a goal.

7.2. Need for Instrumental Support

Instrumental support includes any tangible financial, temporal, labor, and environmental support. Instrumental support by health teams includes the quality of physical and mental care provided to the newborn infants (30).

The quality of infant care is parents’ first priority and assurance about skillful care of the infant reduces their negative feelings, especially in their absence, and increases their trust in medical staff as Fegran suggests (34). However, this feeling does not eliminate the need for having a close parents-child relation.

Parents’ interaction with their newborn infant is a salve to their pain and forced separation is not only an alarm over inefficiency of their presence but also a sign of negligence in their need to stay beside their newborn infant (32). Ignorance of these emotions causes a serious damage to the formation of parent-infant relationship, which should be avoided by removing the limitations on parents’ staying beside their newborn and facilitating physical interactions with his/her by establishing a quiet and pleasant environment for using such creative care methods as KMC (35). In this regard, Wigert, in a study has emphasized the necessity of a maternity ward to be adjacent to the NICU, providing care for mothers and infants together or alternatively, and increasing the number of rooms for the parents (6). In line with the above-mentioned points, Macedo in a comparison between mothers with premature infants in incubators and mothers participated in KMC realized that the mothers in the second group were much more skillful, more right-minded, more sociable, happier, calmer, more satisfied, more energetic, and more harmonious (36).

According to the meta-synthesis’s results, parents’ readiness to take unexpected roles and redefine them within the familial structure is a necessity that makes parents in need of a supportive, welcoming, developing, and relaxing environment. As Obeidat suggested in his study (37), the need for such an environment has defined a type of care, called family-centered care, which is based on family/medical-team collaboration (38).

7.3. Need for Spiritual Support

Many scientists refer to spirituality as an integral part of human existence. The deep heart of spirituality is an inner relationship between the individual and God. Spirituality leads to support, hope and peace, and includes finding meaning, purpose, and direction in life. It is strongly related to religious beliefs and traditions.

In their studies, Obeidat and Wilson showed that during the crisis of illness, spirituality can be an important part of one’s ability to deal with problems and have a positive impact on his/her response, due to the fact that reliance on a higher being’s support can be a source of hope for a positive result (37, 39).

After the recommendation of the world health organization (WHO) in 1998 to add a spiritual dimension to the definition of health, it was considered as an important component of life quality, and widely used as a comprehensive approach to which the whole medical team, especially nurses, should pay special attention to. Khorami emphasized that the self-spirituality and personal development of the medical team in this area affect their capability of comprehensive care communication and if the health team ignores its own spiritual health-related matters, it might encounters with a difficulty in dealing with the spiritual needs of the clients (40).

Islam is the dominant religion in Iran and it literally means submission to God’s will. Being proud of divine bounty and giving thanks to God in difficult situations and submission to his providence is the interpretation of spiritual development to many Iranian religious parents. There are parents who are affected by that shocking circumstance, lose their strength and start grumbling, and even blaspheming. Unfortunately, we should acknowledge that in Iran, the presence of some relatives is distress evoking instead of being a source of support. Their wrong beliefs make parents feel guilty, suggesting that the incident is the punishment for the parents’ sins. In such context, spiritual support has a special place; for example, Reihani, in a study showed that spiritual self-care training resulted in the reduction of mental stress of parents with premature newborns (41), or the study of Hamid supported the positive impact of spiritual activities such as reciting the Quran and prayers to reduce depression and increase immune cells in depressed women (42).

Although everyone acknowledges negative consequences of disregarding spiritual values, parents rarely reported supportive role of the health team in spiritual matters, as Catlin has shown in a study (43). In addition, actual spiritual interventions have not observed adoption of a comprehensive health-care approach, which is the very shortcoming mentioned by Wilson. He believes that parents may lose their trust in the medical staff that only carries torment messages (39).

7.4. Need for Appraisal Support

This type of support means strengthening the parental role and status (30). Guided participation of parents in routine infant’s care can provide the context for this type of support (44). For this purpose, according to the study of Reis, the health team must always be available and provide educational information and encourage participation, while paving the way for independence of the parents in giving care through constructive reforms, prudent and wise guidance, as well as compassionate confirmation (45). They also should help those who, according to Radfar, “are in the rush to play a parental role” (20). In this regard, Fegran believes that nurses can act as a role model and gradually leave more responsibilities to the parents, therefore, changing their role as an observer to an independent actor. He cleverly finds that despite the parents’ impatience for discharge, they find it daunting to take their baby home. On the other hand, their futuristic synergy can be effective in minimizing this emotional contrast (34).

7.5. Need for Informational-Communicational Support

This need emphasizes providing information continuously to parents on infant’s condition, treatment, care and growth, emotional and behavioral needs, as well as responses and parents’ rights and responsibilities during hospitalization (30). In his study, Mok suggests that parents of premature infants, who gradually change from passive observers to active participants, need more information and support, particularly in terms of their specific needs during different phases of hospitalization and after discharge of the newborn infants (3). If we classify information into 4 categories of diagnosis, prognosis, current treatment, and causes of illness according to the study of Perlman, information on current treatment is particularly effective in reducing uncertainty and increasing parents’ coping ability and is demanded by parents (46). Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to collect this information and as the study of Ichijima confirmed, relationship with a staff is one of the most important stressful aspects of parents’ experience in the neonatal unit (47). Power imbalance and parents’ unpleasant experience about the medical team’s response to their informational needs evokes the feeling of helplessness and weakness in the parents (48).

8. Conclusion

Meta-synthesis research findings could be used to develop evidence-based care and guide interventions; therefore, the findings of this study could be used for a better understanding of the experiences of parents with premature infants in Iran and their different needs. Results would be helpful in future studies for designing interventions responding to these needs and providing a basis for designing a comprehensive supportive system for parents which incorporates a holistic view of patient’s concerns, including religion, and spirituality. In addition, training sessions incorporating findings identified in this synthesis could be provided to all professionals who work with new parents of preterm infants.

This study is limited to Iranian mothers and may not be generalizable to all women in other settings. Additionally, due to the fact that publish studies in Journals were included, this meta- synthesis is susceptible to publication bias.