1. Context

One of the most popular endocrine disorders (1, 2) that affects 5% to 10% of females at the reproductive age (3, 4) is Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). However, the rate of PCOS reported in various studies ranges from 2.2% to as high as 26% (5). The endocrinopathy begins at puberty and ends at menopause, which has adverse consequences based on clinical presentation and laboratory findings (6). Since PCOS is associated with a wide range of medical problems, it has gained remarkable attention over the last decade (7). However, a comprehensive and clear explanation for the pathogenesis of this disorder has remained questionable (6, 8). There are several features for characterizing PCOS, such as menstrual disturbances (amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea) and hyperadrogenism (hirsutism or acne, and very often obesity). Besides, chronic anovulation and infertility are the prevalent consequences of PCOS (9). It is common for almost all females diagnosed with PCOS to have negative emotions of frustration, anxiety, and to a lesser extent, sadness (8, 10). However, several disorders such as changes in appearance, irregular or absent menstrual periods, and possibly disturbances in sexual attitudes and behavior (8) can lead to psychological distress and impaired emotional well-being (6, 11). These can impact the patients’ feminine identity and create psychological problems, such as anxiety, depression, as well as marital and social maladjustment (9, 12). Almost all of the females diagnosed with PCOS had experienced significant levels of psychological disorders in all dimensions of their life compared to the general population (13, 14), with anxiety and depression, social interaction, body image and body weight, eating problems, hirsutism, fertility, and decreased Quality of Life (QOL) being the main consequences of psychosocial problems in PCOS (15, 16). The majority of females with PCOS reported problems such as somatization, obsessive–compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility (17). Several other disorders have been reported by females with PCOS, including lower self-esteem, more negative body-image, decreased psychological well-being, impaired social and marital relationships, poor sexual performance (18, 19), and psychological morbidity (20-22). This further indicates the importance of emotional distress and psychiatric disorders in reducing psychosocial aspects of quality of life in PCOS. According to the literature, depression and anxiety are the most common mental symptoms of PCOS, while mood and anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric diagnoses of PCOS (6, 23).

Depression, according to previous research, had the highest prevalence, from 28% to 64%, among patients with PCOS (9, 14). The other symptoms of PCOS included feeling ill, depressed mood, melancholy, and sadness. However, the cause of these disorders was not clear (9). Impact of high androgen levels on mood disturbances can be one of the reasons for the high prevalence of depression. A careful review of previous studies showed that little attention has been paid to psychological aspects of endocrine disorder. One of the most prevalent psychiatric diagnoses among treated endocrine patients and the general population is anxiety disorder. Anxiety and social fears are the two factors that might cause social isolation, impair quality of life, and enhance the risk of additional psychiatric disorders, such as depression and suicidal attempts (2). Persistent fear about loss of sexual function and fertility, as well as anxiety about probable inability of childbirth in the future could be the underlying reasons for the high level of anxiety (24). The literature revealed that there is a lack of clear explanation for the relationship between psychological health aspects and clinical characteristics of PCOS (10, 16). Given the existing lacuna in the literature regarding the psychological aspects of PCOS, this review aimed at exploring the psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome.

2. Evidence Acquisition

This study was a narrative review, conducted in 6 steps: (1) identification of the research question; (2) comprehensive literature search to finding relevant articles; (3) study selection; (4) ethical considerations; (5) data extraction; and (6) presentation of the report in 2 main categories.

2.1. Identification of the Research Question

Given the lack of clarity regarding the psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome, the research question was defined as: What are the psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome?

2.2. Data Sources

Two researchers (Marzieh Azizi and Forouzan Elyasi) searched through the following databases for relevant articles, independently: Google Scholar and more specifically PubMed, ProQuest, Ovid, web of science, Science direct, Magiran, Scientific Information Database (SID), and IranMedex. The following key search terms (as per the MeSH) were used to retrieve articles published between 1983 and 2016: (Polycystic ovarian syndrome) and (mood disorders OR psychological issues OR psychological problems OR borderline personality disorder OR personality disorder) and (stress OR coping styles) and (physical symptoms OR obesity OR sexual dysfunction OR quality of life).

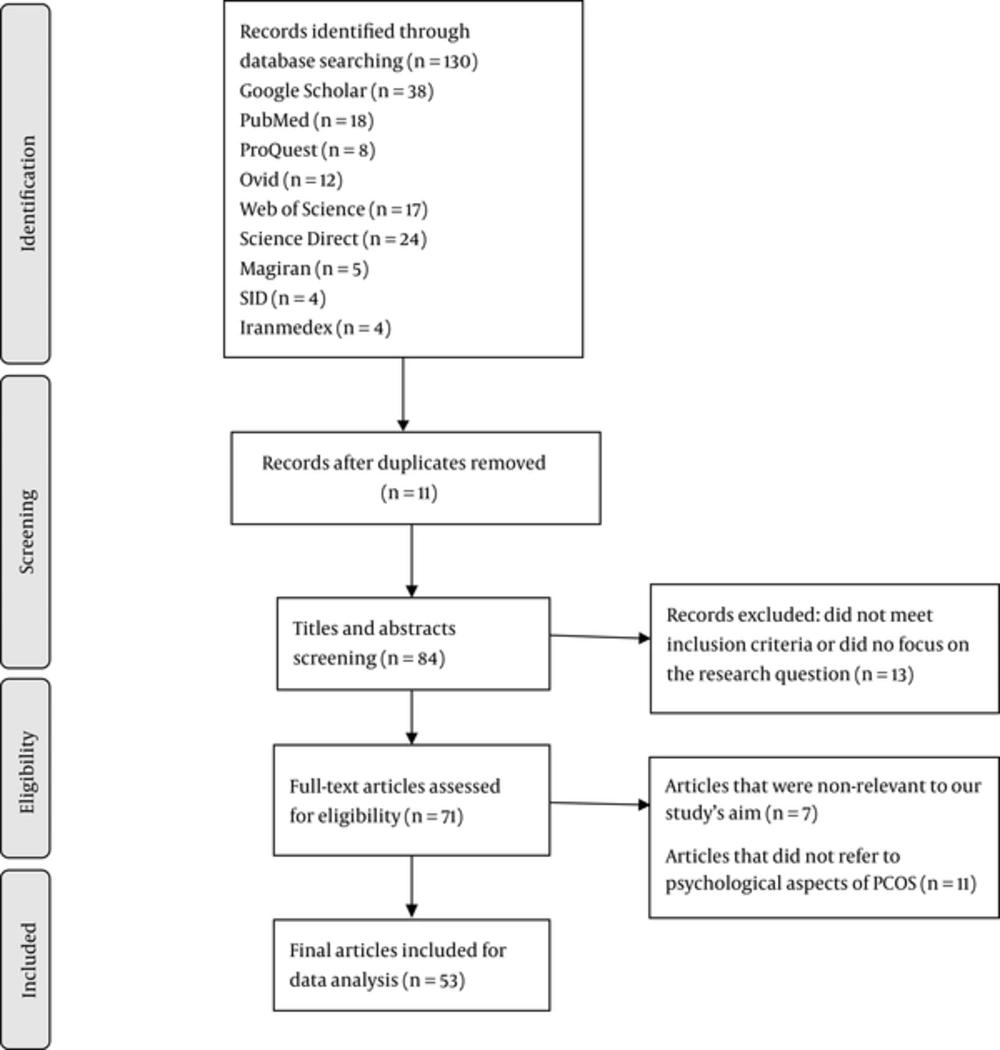

2.3. Study Selection

The initial literature search yielded 130 articles. Two researchers (Marzieh Azizi and Forouzan Elyasi) independently conducted the screening of titles and abstracts, and chose relevant articles according to the following inclusion criteria: publication in scientific journals; a focus on psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome, and including patients with no previous psychiatric disorders. The screening led to the exclusion of 35 articles. After deleting repeated citations (n = 11), 84 articles remained. During abstract screening, 13 articles were excluded due to a lack of focus on the mentioned research question. Also, during full-text review and appraisal, articles that did not refer to psychological aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome (n = 11) or had aims other than that of the current review (n = 7) were excluded. Finally, 53 articles remained for study inclusion (Figure 1).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations and the general standards for publication with respect to plagiarism, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, and so forth were completely respected by the authors of this study.

2.5. Data Extraction

The full text of each included article was read carefully, and relevant and required data for the compilation of findings was extracted and categorized.

2.6. Presentation of the Report in 2 Main Categories

The findings regarding psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome were allocated to 2 main categories and 9 subcategories.

3. Results

The 2 main categories were: (a) Psychosocial concerns related to PCOS, including body dissatisfaction, body weight and body-image disturbances, sexual and relational functioning, femininity, fertility and sexuality concerns, health-related quality of life, stress and coping responses, general fatigue, loss of self-confidence, and hostility/cynicism; and (b) Psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and borderline personality disorder (Table 1).

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Psychosocial concern related to PCOS | |

| Body dissatisfaction, Body weight and body-image disturbances | (Bazarganipour et al., 2014), (Kitzinger and Willmott, 2002), (Deeks et al., 2011), (Lee, 2015), (Michelmore et al., 2001). |

| Sexual and Relational Functioning | (Silva et al., 2010), (Tan et al., 2008), (Eftekhar et al., 2014). |

| Health-Related Quality of Life | (Elsenbruch et al., 2006), (Shakerardekani et al., 2011), (Moghadam and Hajloo, 2015), (Himelein and Thatcher, 2006b). |

| Stress and Coping Responses | (Lobo et al., 1983), (Ozenl et al., 2009), (Benson et al., 2010). |

| Psychiatric disorders | |

| Depression | (Hollinrake et al., 2007), (Himelein and Thatcher, 2006a), (Kerchner et al., 2009), (Benson et al., 2008). |

| Bipolar disorders | (Krepuła et al., 2012), (Davari-Tanha et al., 2014), (McIntyre et al., 2003), (Rassi et al., 2010). |

| Anxiety disorders | (Benson et al., 2009), (Podfigurna-Stopa et al., 2015), (Harmanci et al., 2013), (Hussain et al., 2015), (Deeks et al., 2011). |

| Eating disorders | (Krepuła et al., 2012), (Sayyah-Melli et al., 2015), (Michelmore et al., 2001), (Lee, 2015). |

| Borderline personality disorder | (Shao et al., 2015), (Kawamura et al., 2011), (Bassett, 2015), (Sahingoz et al., 2013), (Sharma, 2015). |

3.1. Psychosocial Concern Related to PCOS

3.1.1. Body Dissatisfaction, Body Weight and Body-Image Disturbances

Body image refers to the mental picture of someone’s body, an attitude about physical self-appearance, wholeness, normal function, and sexuality. For females, body image has the elements of feminine and attractiveness that can be a symbol of social demonstration (25). Therefore, negative perception among PCOS patients regarding their body image leads to a feeling of dissatisfied, and less self-consciousness with their appearance, loss of femininity, feeling less sexually attractive, and being unable to adapt to the normal society (25-27). As found in prior studies, symptoms such as hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility (15) are painful, uncomfortable, and unpredictable for many PCOS patients because these symptoms are culturally defined as unfeminine and undesirable (28, 29). Perhaps, losing femininity in females with PCOS can result in feelings of stigmatized and mood disorders such as depression, limited sense of well-being, and dissatisfaction with life (19). Additionally, one of the reasons causing eating disorder is body dissatisfaction. This is because self-esteem, as an important element for a female’s social function and interpersonal relationships, is exclusively based on their body image (25). Another factor that affects the body image of females with PCOS is their weight. This could be rooted in cultural preferences that consider android fat pattern as unattractive (30). Obesity or weight gain might lead to a loss of self-esteem as well as poor body image and body satisfaction. This can ultimately reduce their quality of life while increasing their psychological disorders (15). Therefore, is it paramount to carefully identify the patients’ emotional well-being, which is particularly related to low self-esteem, poor body image and weight challenges, menstrual abnormalities, and hirsutism (25).

3.1.2. Sexual and Relational Functioning

Patients with PCOS experience multi-symptomatic changes that may influence their sexual functioning (11, 29, 31). There are a very limited number of studies on the PCOS of patients’ sexual functioning (32). Several factors, which have been found to negatively impact quality of life, sexual dissatisfaction, and self-worth, include changes in body appearance, especially obesity and excessive body hair (18). Furthermore, another stressor for patients with PCOS is infertility that can negatively influence the couples’ life, their marital relationships, and sexual performance (19). Some other factors that can be related to sexual dysfunction are depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and negative self-image (32). In previous studies, patients with PCOS have reported their partners were less sexually satisfied and less sexually attracted to them. Moreover, females with PCOS experienced lower levels of sexual thoughts and desires than the general healthy population (25, 31, 33). Overall, in females with PCOS, the syndrome does not cause sexual initiation (forms of expressing sexuality), intimate communication with partners, and sexual satisfaction (11). Although it is hypothesized that female libido increases with elevated androgen levels in PCOS, females with PCOS reported a decrease in libido and satisfaction (33). Hence, no significant relationship has been established between androgen levels and sexual functioning. In summary, sexual functioning is very much dependent on psychological factors and the relationship between partners. Similarly, a study of married Iranian females with polycystic ovary syndrome indicated that the most common sexual dysfunction was related to hypoactive desire disorder and arousal disorder (31).

3.1.3. Health-Related Quality of Life

Low Quality of Life (QOL) and impaired emotional and psychological well-being are the main concerns of females with PCOS (3, 12, 19). Understanding the factors influencing reduction of quality of life in females with PCOS remains relatively doubtful. It seems that biochemical, hormonal, metabolic, and physical problems play essential roles in decreasing PCOS patients’ QOL and psychological well-being (16, 31). Based on the findings of the majority of studies in this area, obesity has been found as the most substantial factor that lowers QOL in PCOS patients (34). Moreover, infertility has been found as the second most crucial factor that negatively influences PCOS patients’ QOL (16). This is especially more important in cultures that have strong expectations from females to have children (31). The other 2 factors that are critical in reducing QOL of females with PCOS are hirsutism and hair loss (16, 35). As such, life events are more stressful for these patients, which can increase their psychological difficulties. Several other common mental problems such as anxiety, depression, aggression (28), body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, and sexual dissatisfaction may significantly reduce the patients’ quality of life in physical, mental, and sexual dimensions (6, 32). Overall, reduction in psychosocial aspects of quality of life in patients with PCOS depends on emotional distress and psychiatric disorders (10, 15).

3.1.4. Stress and Coping Responses

Experiencing stress in modern societies is an inseparable part of people’s lives. In psychological context, stress refers to a condition in which homeostasis is jeopardized by action of external (environmental) and internal (physiological and psychological states) stressors. In particular, stress is the experience of a perceived threat, resulting from a series of physiological responses and pathways (36). Stress can impact the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and immune function, as well as peripheral and central dysregulation of opioid system. Psychological stress can also effect carbohydrate metabolism that is a cause of PCOS-related pathophysiology (6). Findings of a study on psychological stress and its probable relationship with hormonal parameters revealed that patients with PCOS had higher stress rate than the general population. Besides, in patients with PCOS, the level of physiological stress hormone was high (37). Moreover, compared to healthy controls, patients with PCOS had significantly higher helplessness, self-blaming, and responsibility response acceptance. There are 2 main psychological ways to cope with stress namely direct and indirect. The direct way of coping focuses on the problem. More specifically, individuals by evaluating the stressful situation and taking some actions to change or avoid it can directly cope with their stress. This is also known as a problem-focused coping response. The indirect pathway, however, focuses on the emotional response to the problem. In other words, individuals try to reduce anxiety without dealing with the anxiety created by the situation. The indirect way of coping with stress is also called emotion-focused coping response. Helplessness and self-blame are indirect ways of coping with stress or are known as emotion-focused coping strategies, which are considered effective (38, 39). There are a few studies in the literature, which show that females with PCOS commonly cope with stress via the emotion-focused pathway. Females with PCOS are more likely to use helplessness, self-blame, and accepting responsibility, which are unwillingly applied in their daily life compared to problem-focused coping. Emotion focused coping strategies are considered as passive methods. Therefore, these passive patterns of patients with PCOS in response to stressful situations may play a primary role in developing psychosomatic disorders (37, 38).

3.2. Psychiatric Disorders

3.2.1. Depression

The risk of depression is yet unclear in females with PCOS (20). Nonetheless, studies that have investigated psychological causes of PCOS have found a relationship between depression and PCOS (7). A large number of behavioral scientists have examined the symptoms of depression (31). Depressive disorders include major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder and depressive disorder not otherwise specified, based on the diagnostic and statistical manual IV (DSM-IV), which are observable in PCOS patients (7, 20). Prior studies have found that depression increases cortisol levels while it decreases serotonin levels in the central nervous system (10, 22). According to the findings of several studies in this area, 28% to 64% of patients with PCOS had depression (40). The variation in prevalence of depression among studies can be due to the application of different methods and tools for screening and diagnosing the influence of culture on epidemiology of depression and recent use of medication (24). The most commonly reported symptoms by these patients were fatigue and sleep disturbances (23). There are several hypotheses about the causes of depression in patients with PCOS. One of the most critical causes of depression in patients with PCOS is increased body mass index, which is accompanied by negative perception towards their body (41). Approximately, two-thirds of females with PCOS are overweight or obese (42, 43). One of the main causes of depression in females of the general population is obesity. However, there are inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between obesity and depression in females with PCOS. Such relationship has not been supported by several earlier studies. For instance, Benson revealed that there was no association between depression and obesity in patients with PCOS (42). The other possibility for depression in patients with PCOS could be due to the link between excess androgen and mood disorder. This possibility has remained controversial since clinical and biochemical biomarkers of hyperandrogenism seem not to be the direct cause of depression (40).

3.2.2. Bipolar Disorders

One of the psychological disorders that can significantly change mood, behavior, thoughts, and energy level is bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is characterized by alternating occurrence of episodes of mania and depression. There are three types of bipolar disorder, namely bipolar disorder I (mania and major depression), bipolar disorder II (hypomania and episodes of major depression), and unspecified bipolar disorder (not meeting the criteria of I or II). The incidence of bipolar disorder is 1% (16). The relationship between bipolar disorder and PCOS has not yet been supported in the literature and there is little evidence in this regard. There are also contradictory and inconsistent opinions regarding such relationship. According to some researchers, valproic acid (VPA), which is used for treating bipolar disorder, highly influences development of PCOS (31). Other studies state that these 2 disorders are directly linked. Specifically, hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary (HPO) level and likeness of metabolic abnormalities are common disturbances in both PCOS and bipolar disorder (16).

Compared to the healthy population, bipolar patients experience mental and physical issues (44). Prior studies have demonstrated the existence of several PCOS disturbances such as menstrual irregularities, hyperandrogenism, and anatomic or hormonal evidences in bipolar females (44). Findings of a study revealed that bipolar females treated with valproate had a higher level of menstrual irregularities, hyperandrogenism, and metabolic syndrome than females without treatment (45). This is mainly due to the medications used for treating bipolar disorder that could influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and the reproductive system (46). There is no evidence to support that valproate therapy independently induces PCOS. Thus, based on the findings of several biochemical studies, prolonged valproate therapy can lead to increased ovarian androgen biosynthesis. This is a potential mechanism, by which valproate could induce PCOS symptoms (31).

3.2.3. Anxiety Disorders

Another common disturbance that causes difficulty for females with PCOS is anxiety, which has a prevalence rate of 34% to 57% (9). One of the main reasons for anxiety is persistent fears regarding loss of sexuality, loss of fertility, and inability to have children (24). There are other PCOS symptoms such as hirsutism, acne (23), obesity, and menstrual irregularities that might cause anxiety in PCOS patients (28). Moreover, females with PCOS experience higher level of anxiety because of masculine body features, which is the result of increased level of androgen, and also awareness regarding possible chronic disorders (23). The underlying reason for development of depressive disorders is anxiety. Based on earlier findings, anxiety disorders are more prevalent than depression in patients with PCOS (2, 23). Anxiety, as a strong predictor of functional impairment, has major effects on the role of function and quality of life in patients with PCOS (24). As indicated by the literature, patients with PCOS have social phobia, specific phobia, and panic disorder (23). Negative reactions from people towards obesity and hirsutism might trigger social phobia (24). Overall, there is limited research regarding the link between anxiety and PCOS (47). Consequently, greater rate of anxiety in females with PCOS could be a byproduct of overall negative effects rather than independent problems (23).

3.2.4. Eating Disorders

There are 3 types of eating disorders according to diagnostic and statistical manual IV (DSM-IV) that include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and periodic overeating, such as binge-eating disorder (16). It has been reported that the rate of eating disorders and suicidal behavior among females with PCOS is increasing (6). Females with eating disorders often behave secretly about their eating problem and weight control. Those with bulimia nervosa are generally ashamed of their eating habits. This has caused females with eating disorders to be reluctant in exposing and discussing their eating habits (28). It has been stated in several earlier studies that there is a relationship between PCOS and eating disorders. However, the etiology of such relationship has never been satisfactorily clarified (20, 44). Several theories have been proposed that can explain the association between PCOS and bulimia nervosa (28). One of the possibilities is emotional distress that brings about adverse symptoms of PCOS such as hirsutism, acne, menstrual irregularity, and obesity. These symptoms might develop eating disorders (15, 28). As revealed in an early study, being overweight or obese may lead to unhealthy eating habits such as binge eating purging, vomiting, dieting, and use of diuretics or laxatives to lose weight. As such, dissatisfaction with self-appearance in some adolescents with PCOS might cause them to think that their attempt for losing weight is not as successful as that of their peers without PCOS (15). Moreover, bulimia nervosa, by creating a hormonal environment, predisposes polycystic ovarian changes. One of the potential mechanisms is altered insulin secretion and insulin resistance in females with bulimia, however, the views regarding this mechanism varies in the literature (28). Hence, it is of uttermost importance to clinically screen females with PCOS for their abnormal eating behavior prior to suggesting any diet.

3.2.5. Borderline Personality Disorders

In comparison with healthy females, those with PCOS experience relevant personality and psychiatric comorbidities (40). Borderline Personality disorder (BPD) is a serious public health problem that is characterized by interpersonal distress, affective instability, stress-related dissociation, and chronic suicidal tendencies (48). Approximately, more than half of patients with BPD report a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). The elevated level of Interleukin (IL)-6 in serum is considered a possible biomarker of BPD, which is associated with MDD (48). Additionally, there is a significant relationship between BPD and bipolar disorders as well as disruptions of gonadal hormone regulation (including estrogen), which have been identified in bipolar disorder (49). It has been revealed by several studies that PCOS has an association with personality disorders (including BPD), and emotional-behavioral difficulties. However, there is no clear explanation regarding its exact mechanism (49, 50). An early study proposed 3 hypotheses as the possible mechanisms for borderline traits observed in both PCOS and BPD. These mechanisms include serotonin hypothesis, HPA axis disturbance hypothesis, and female hormone disturbance hypothesis (21).

Given the large number of psychiatric issues involved in borderline personality disorder, it is recommended for physicians to apply screening BPD diagnostic criteria to identify females with PCOS, who are at risk of future psychiatric hospitalizations or suicidal attempts. Furthermore, providing psychosocial support including positive, and respectful attitude can be an effective tool to understand the patient’s worries and needs associated with PCOS (21).

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome. The findings revealed that patients with PCOS experience a great deal of stressful life events that can lead to psychological difficulties (6). Additionally, these patients are more susceptible to develop anxiety disorders, depression, personality, and other psychological disorders (6, 50). Psychological distress has roots in several important factors such as changes in appearance, irregular or absent menstrual periods, and disturbances in sexual attitudes and behavior (8). Based on the findings of a prior study, in comparison with the healthy population, patients with PCOS are more neurotic, anxious, and depressed (10). The reason for such vulnerability of PCOS patients to psychiatric disorders still remains unclear. The mechanism for such psychological disorders has not yet been determined. One potential cause for inducing psychological disorders through hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and circadian pattern is stress (6). The current study findings are in agreement with several previous studies that suggested chronic, complex, and often frustrating nature of PCOS frequently leads to negative psychological outcomes that may lead to decreased motivation and confidence. Since motivation and confidence are the two essential aspects of treatment of lifestyle modification, they are very detrimental for PCOS patients (47, 51).

Management of PCOS should be carried out in multistage processes and encompass both physical and psychological domains. It should consider psychological screening for adverse psychosocial effects of PCOS, mental health approaches, lifestyle changes, medications and psychological counseling.

Mental health-related issues should be part of the initial screening and evaluation (24). Assessing mental health symptomatology, especially depression through patient health questionnaire-9, should be involved in psychological screening (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9, which is a self-report scale has been shown to be an appropriate tool for detecting depression in primary care (31). One of the most effective approaches for treating psychological problems (mood and anxiety disorders) is the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. This approach is better than medication alone. Mental health approaches are multidimensional processes that involve weekly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) sessions. These therapy sessions can be conducted with participation of individual, and family members as well as support groups by meeting in person or online (15). Since these approaches promote a healthy lifestyle for patients, they are considered effective.

One of the most crucial and effective treatments for PCOS is lifestyle interventions. Even minor lifestyle interventions are important for the improvement of symptoms, decrease of weight, and improvement of fertility in patients with PCOS. The other important factor for PCOS patients that prompts intervention and improves self-efficacy is psychological well-being (47). Life style interventions include identifying patients’ unsafe weight-loss strategies and eating patterns (15) and encouraging them to use an appropriate plan for weight loss of 5% to 10% (52). It also involves advising patients to do regular physical exercise (15). As proven in a prior study, yoga significantly increases HQOL of PCOS patients compared to traditional physical exercises (53).

It has been advised that patients with PCOS can take oral contraceptives to regulate menstrual cycle medications to treat hirsutism and acne. The other solution is cosmetic therapy such as laser treatment. As has been shown, females with hirsutism had enhanced self-esteem after effective hair removal. If cosmetic therapy is not effective or unaffordable for patients, who are concerned with hirsutism, there is another option, which is medical therapy (52). To treat underlying insulin resistance, insulin sensitizers such as metformin can be used (15). Anti-androgens such as spironolactone can be helpful in managing hyperandrogenism effects (31). Antidepressants and other psychotropic can be used to treat psychiatric disorders related to PCOS (15). Psychological consultation with psychologists or psychiatrists is the most effective way to determine the severity of and appropriate treatment for PCOS patients (22). It is also suggested that through providing psychosocial education and support for patients with PCOS, nurses and other healthcare providers can help improve coping strategies in patients.

The limitations of this study included a lack of assessment of the quality of included articles. Also this study used articles only in English language and studies written in other languages such as Persian and non-English studies were ignored.

Given the mentioned limitations, the researchers propose that a systematic review or clinical trials regarding management of psychosomatic aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome and also psychiatric disorders in these patients will be required and useful.

4.1. Conclusion

Polycystic ovarian syndrome is a multi-symptomatic disease that encompasses a number of physical and psychological consequences. Various factors play crucial roles in reducing psychological health in PCOS patients. These factors include coping with the condition, feeling fears regarding infertility, losing femininity, having a less attractive body, and being concerned with body disturbance (9). Through a review of the literature, this study suggests that screening and treating patients with PCOS should be carried out by care and awareness by clinicians since these patients are the high risk group for common mood and anxiety disorders as well as suicide attempts. Thus, a holistic treatment approach is required for patients with PCOS. Prior to any optimal intervention, patient’s psychological and social conditions should be considered. Moreover, patients should receive counseling by a psychiatrist or healthcare professional for their treatment and care in order to achieve long-term emotional well-being. In conclusion, due to the high prevalence and serious implications of anxiety and depression in females with PCOS, clinicians should be aware of such psychiatric comorbidities. They also need to ensure that patients receive adequate psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatment. Besides, by providing psychosocial education and support for PCOS patients, nurses and health care providers can help patients improve their coping strategies.