1. Background

In DSM-5, the body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is classified as the obsessive-compulsive disorder and other relevant disorders. It is mainly characterized by a preoccupation with one or more imaginary flaws or defects in the appearance. People with BDD believe that they look ugly, unattractive, abnormal, or dysmorphic (1). The prevalence of BDD has been reported to be higher in some groups such as students (2, 3). It was reported as 4% among US students and 8.4% in Turkey (4, 5). According to the results of investigating the prevalence of BDD among students at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, 34.4% of the participants expressed concerns about their appearances and the prevalence of BDD was 7.4% among the students (6).

Self-compassion is a variable considered by researchers in relation to dissatisfaction with body image and eating behaviors in recent years (7-14). Since 2003 when Kristin Neff introduced self-compassion as a structure and presented some tools to measure it, nearly 200 theses and papers have dealt with it (15). Self-compassion indicates that a person treats himself kindly in pain and difficulties, understands and acknowledges his transient nature, and considers his experience to be part of common human experiences. Neff introduced three components of self-compassion having internal relationships with each other. Each component consists of a positive aspect and a negative aspect, including self-kindness against self-judgment, common humanity against isolation, and mindfulness against over-identification (16).

MacBeth and Gumley investigated the relationship between self-compassion and psychopathology in a meta-analysis of 20 studies and obtained high effect size. Increasing evidence indicates that self-compassion is related to psychological well-being and it is regarded as an important protective factor (17). Studies showed that self-compassion is positively related to satisfaction with life, happiness, optimism, wisdom, personal innovation, and creativity. They also indicated that it is negatively related to depression, anxiety, negative affect, rumination, and thought suppression (16, 18, 19).

Kelly and Stephen found that daily within-person and interpersonal fluctuations in self-compassion of female students could affect their body image and eating behaviors. Such findings were also true after controlling for the role of self-esteem (7). In another study of the relationship between compassion and body image, the results indicated that self-compassion predicted a separate variance of preoccupation with the body, concern about weight, and feeling of guilt about eating regardless of self-esteem (10).

According to Braun et al., self-compassion can serve as a protective factor against poor body image and in the psychopathology of eating in different forms. First, self-compassion may directly decrease the adverse consequences of negative body image or the psychopathology of eating. Second, self-compassion may prevent risk factors from emerging. Third, self-compassion may interact with risk factors and stop their devastating effects. Finally, self-compassion may stop the mediating chain by which risk factors operate (11).

In addition to the protective role of self-compassion, a series of risk factors were also investigated in relation to body image and eating behaviors. Shame (20), perfectionism (21), and negative affect (22) are such risk factors. External shame and self-compassion are related to dissatisfaction with the body in public communities and eating disorders (23). In fact, there are two types of shame: internal shame and external shame. Regarding internal shame (the first component), an individual focuses on himself and sees himself as incompetent, faulty, or bad. Regarding external shame (the second component), an individual focuses on what others think about him. Here, the self is perceived as unattractive (24). Liss and Erchull found that body checking had strong significant relationships with body shame and negative attitudes among subjects with low self-compassion (25). Many studies indicated that higher levels of negative affect were related to dissatisfaction with the body (26) and body image distortion (27, 28).

Other studies indicated a relationship between perfectionism and satisfaction with body image. In other words, perfectionism can serve as a risk factor for dissatisfaction with body image and eating behavior disorders (29-32). In a large nonclinical student sample, Bartsch found out that the two subscales of self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism could predict concern about body dysmorphia (33). In a clinical sample, Buhlmann et al. reported that people with BDD had significantly higher scores than a control group on “concern over mistakes” and “doubt about actions” subscales of Frost’s multidimensional perfectionism (34). Barnett and Sharp studied the mediating role of self-compassion in relationships of disordered eating behaviors with maladaptive perfectionism and satisfaction with body image. The results indicated that self-compassion played a mediating role in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and satisfaction with body image; however, this role was not observed in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and disordered eating behaviors (35).

2. Objectives

Overall, many studies indicated that shame, perfectionism, and negative affect could serve as risk factors for dissatisfaction with the body. Nevertheless, other studies showed the protective and mediating role of self-compassion. In this study, the path analysis was used to determine the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship of concern about body dysmorphia with risk factors such as shame, perfectionism, and negative affect.

3. Materials and Methods

This is an applied-descriptive study in which structural equation modeling (SEM) was used as a multivariate correlation method. The SEM is actually the expansion of general linear modeling (GLM) enabling researchers to test a group of regression models at the same time. The statistical population included all Bachelor, Master, and Ph.D. students at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. In the SEM, a sample size of greater than 200 is satisfactory (36). Thus, a convenience sampling method was used to select 210 students (103 males and 107 females).

3.1. Research Tools

3.1.1. Dysmorphic Concern Questionnaire (DCQ)

This questionnaire includes seven items measuring concern about physical appearance. They are rated on a four-point Likert scale (0 - 3), with the highest score showing the highest level of concern. DCQ is a dimensional scale on concern about appearance. It has been used in many clinical settings (37-39). The scores of DCQ are strongly correlated with the scores of body dysmorphic disorder examination, which is a reliable and valid scale of BDD (40). Although DCQ does not measure BDD directly, it can evaluate clinical and subclinical concerns about appearance without any prejudgments on etiology and pathology (38). In Iran, research results supported the single-factor structure of concern about BDD in a national sample (RMSE = 0.07, NFI = 0.94, and CFI = 0.97), with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 (41).

3.1.2. Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) Short-Form

This scale includes 12 items based on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (nearly never) to 5 (nearly always). The SCS measures three bipolar components in six subscales including self-compassion versus self-judgment, mindfulness versus over-identification, and common humanity versus isolation. The short-form SCS was correlated with its long form (r = 0.97) and its retest reliability was reported as 0.92 (42). In Iran, research results supported the three-factor structure of self-compassion in a national sample (RMSEA = 0.08, NFI = 0.94, and CFI = 0.97), with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 (43).

3.1.3. External Shame Scale

This scale is an 18-item self-report tool designed by Gross et al. to measure external shame. It has been inspired by the Internal Shame Scale. It uses a five-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = nearly always) to score each item. The reliability of this scale was high with Cronbach’s alpha and five-week retest reliability of 0.94 and 0.94, respectively. This scale was moderately correlated with the negative evaluation of fear; however, it was highly correlated with other shame measurement tools in clinical and student populations (44). In Iran, research results supported the three-factor external shame in a student sample (RMSEA = 0.09, NFI = 0.94, and CFI = 0.96), with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for the total scale (45).

3.1.4. Negative Affect Scale

This scale has been driven from the 20-Item Negative and Positive Affect Scale designed by Watson et al. The negative affect subscale includes 10 items rated on a five-point scale (from 1 = very low to 5 = very high). Cronbach’s alpha and eight-week retest reliability were 0.87 and 0.71, respectively. The correlations of this scale with Beck’s Depression Inventory and the State Anxiety Questionnaire (taken from the State-Trait Anxiety Questionnaire) were 0.58 and 0.51, respectively (46). In a study conducted in Iran, the results of confirmatory factor analysis and SEM indicated that the two-factor model was the most appropriate one (47).

3.1.5. Ahvaz Perfectionism Scale

This is a 27-item self-report scale in which each item is scored based on the four-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = often). The scores of all items are summed up to obtain the total score of perfectionism. Higher scores indicate higher levels of perfectionism. Cronbach’s alpha and four-week retest reliability were reported as 0.89 and 0.68, respectively. According to the Pearson correlation coefficient, the scores of subjects on perfectionism were correlated with the scores on Cooper-Smith self-esteem inventory (r = 0.39) and the symptom checklist-90 (r = 0.41) (48).

After making necessary coordination, the data were collected to determine the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationships of concern about body dysmorphia with external shame, perfectionism, and negative affect. The inclusion criteria included being a student, and willingness to cooperate in research, not having severe mental disorders and physical illnesses, and not taking psychiatric drugs. The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to continue participation in the study. Before filling out the research tools, the participants were provided with both oral and written explanations (as in an attachment to questionnaires) to highlight the importance of research into concern about body dysmorphia and relevant factors. All of the participants were free to take part in this study. For the sake of ethical considerations, they were reassured that the collected information would be analyzed in groups. The research goals were explained to them, too. Then, the Pearson correlation coefficient and SEM path analysis were conducted to analyze the obtained data in SPSS V. 18 and LISREL V. 8.

4. Results

There were 210 students aged between 18 and 32 years (mean age: 39.2 ± 10.22), including 131 bachelor students (62.4%), 53 master students (25.2%), and 26 Ph.D. students (4.12%). Table 1 shows the total score of concern about body dysmorphia in males and females, which shows no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05).

| Gender | Number of Samples | Mean | SD | Standard Error of Mean | t | df | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 107 | 12.19 | 3.15 | 0.30 | -0.999 | 208 | 0.321 |

| Males | 103 | 11.72 | 3.65 | 0.36 |

Abbreviations: df, degree of freedom; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the relationships of concern about body dysmorphia with self-compassion, external shame, perfectionism, and negative affect. There was a significant negative relationship between concern about body dysmorphia and self-compassion (P < 0.01 and r = -0.33). The more concern about body dysmorphia was related to a higher rate of external shame (P < 0.01 and r = 0.37), perfectionism (P < 0.01 and r = 0.25), and negative affect (P < 0.01 and r = 32). Self-compassion had significant negative relationships with external shame (P < 0.01 and r = -0.33), perfectionism (P < 0.01 and r = -0.36), and negative affect (P < 0.01 and r = -0.44).

aP < 0.01.

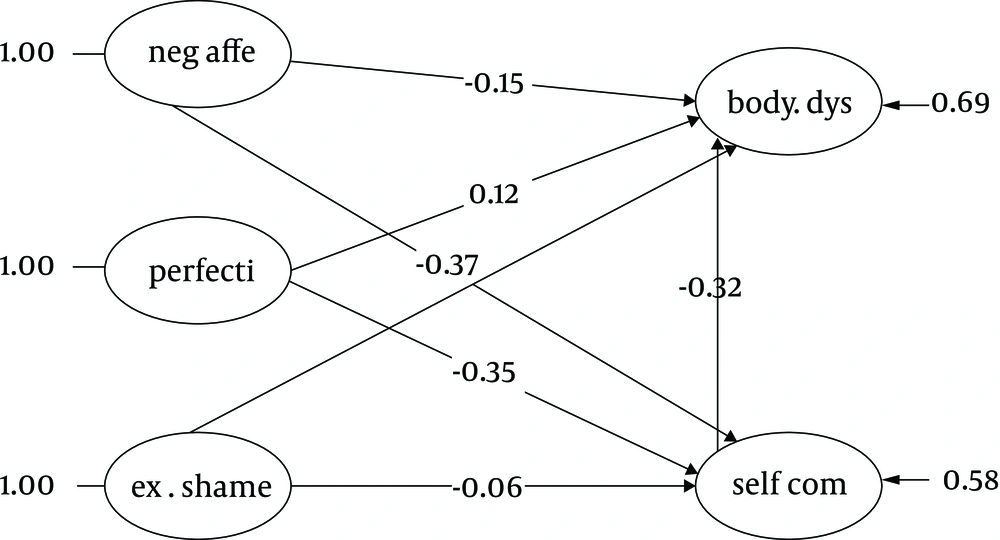

In this study, we considered the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship of concern about body dysmorphia with external shame, perfectionism, and negative affect to investigate the assumed model. First, the pre-assumptions of SEM were checked. According to these assumptions, the data level should be an interval for all variables and data should be normal. Moreover, there should not be any outliers and data should be linear without any multiple collinearities. The pre-assumptions were all checked. The fitness indicators were obtained after testing the proposed model (χ2 = 15.635, df = 339, P = 0.001, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06, IFI = 0.93, NNFI = 0.93, and GFI = 0.82). Therefore, the proposed model fitted the data adequately.

According to Figure 1, external shame had direct (β = 0.40, P = 0.001) and indirect (β = 0.02, P = 0.1) coefficients in concern about body dysmorphia. Moreover, negative affect had direct (β = 0.15, P = 0.05) and indirect (β = 0.12, P = 0.05) coefficients in concern about body dysmorphia. Likewise, perfectionism had direct (β = 0.12, P = 0.05) and indirect (β = 0.11, P = 0.05) coefficients in concern about body dysmorphia. Finally, self-compassion had only a direct coefficient (β = 0.32, P = 0.001) in concern about body dysmorphia. External shame (β = 0.06, P = 0.1), negative affect (β = 0.37, P = 0.001), and perfectionism (β = 0.35, P = 0.001) had direct coefficients in self-compassion.

5. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to investigate the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship of concern about body dysmorphia with external shame, negative affect, and perfectionism. The results showed a significant positive relationship between external shame and concern about body dysmorphia, which is consistent with the results of previous studies conducted by Weingarden et al. (20). As discussed, some authors considered the two aspects of shame: external shame and internal shame (24). It appears that an individual’s evaluation of what others think about him (external shame) is related to concern about body dysmorphia. In external shame, the self is perceived as unattractive. External shame consists of three factors: feeling of inferiority, feeling of emptiness, and being ashamed of making mistakes. In both the Iranian sample and the original sample, most items of the scale are about the feeling of inferiority (44). Accordingly, it appears that the majority of the individuals that have the feeling of shame and humiliation very often are more concerned about their physical shapes.

Moreover, there was a significant positive relationship between negative affect and concern about body dysmorphia. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies (26, 49) showing that positive/negative affect was related to concern about body image and body dysmorphia. Many studies indicated that dissatisfaction with the body could influence a negative mood. Nevertheless, findings show that the negative mood is a risk factor and a maintaining factor for dissatisfaction with the body (50). Theoretically, the negative mood can result in dissatisfaction with the body because it may increase the focus on negative feelings, for example, about weight and appearance (51).

According to the results of the current study, a higher level of perfectionism is related to more concern about body dysmorphia. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies (29, 32, 33). Buhlmann et al. studied the relationship between BDD and perfectionism. They described the common idea of such patients as: “I will not be able to be happy until I look imperfect” (34). It appears that perfectionism is a major component of BDD because such patients insist that a specific part of their bodies must look totally imperfect.

There was a significant negative relationship between self-compassion and concern about body dysmorphia. Moreover, self-compassion could significantly mediate the relationships of concern about body dysmorphia with perfectionism and negative affect. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies indicating that self-compassion plays a protective role in body image and eating behaviors (7, 10). Self-compassion consists of three dual-aspect components. The healthy aspects of these three components are self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (16), all of which can serve as a protective factor against perfectionism and negative affect. According to Shafran’s model for perfectionism, the self-esteem of perfectionists depends on high criteria they define for themselves. If such criteria are not met, they start self-blaming (52). Self-compassion helps these people to admit their mistakes and treat themselves kindly in difficulties instead of criticizing themselves. It should also be taken into account that everyone has certain flaws, and pain and discomfort are common human experiences. Another healthy aspect of self-compassion is mindfulness that can serve as a protective factor against negative affect and perfectionism. It can also moderate the chains of effects on concern about body dysmorphia. Mindfulness helps people acknowledge the transient nature of experiences and do not regard them as facts, instead of engaging in over-identification with experiences and ruminating about them (53).

However, self-compassion could not significantly mediate the relationship between external shame and concern about body dysmorphia. This finding is inconsistent with the results of studies conducted by Liss and Erchull (25) and Ferreira et al. (23). One reason for this incongruence may be that external shame was used in the current study. It appears that external shame is an interpersonal component rather than a within-person component. Therefore, self-compassion could not play a mediating role. Gee and Troop found that the feeling of shame measured by external shame was more related to the symptoms of depression (54). However, the predicted variable of the current study was the concern about body dysmorphia.

5.1. Research Limitations

There were some research constraints that can be considered for future studies. First, this study utilized a cross-sectional correlational design that could not lead to causality. Thus, experimental designs can be used in future studies. Second, the research data were obtained by self-report tools in which the responses might be biased with a chance of socially appropriate responses. Third, the research sample was selected from a nonclinical population of students. It is necessary to conduct similar studies on clinical and general populations. Fourth, only was the external shame measured in this study. Therefore, further studies can investigate both aspects of shame (internal and external).

5.2. Clinical Application

Given the relationships of concern about body dysmorphia with external shame, negative affect, and perfectionism, certain interventions can be designed to decrease concern about body image and body dysmorphia. According to the research results and the mediating role of self-compassion, certain treatments can be used to increase self-compassion such as the compassion-focused therapy (CFT) and mindful self-compassion (MSC) program to help such patients.

5.3. Conclusions

The results of the current study showed that external shame, negative affect, and perfectionism were the risk factors for concern about body dysmorphia. Self-compassion played a mediating role in relation to the above-mentioned factors. Therefore, it is necessary to design interventions to increase self-compassion and decrease concern about body dysmorphia.