1. Background

People are constantly facing internal changes and evolution of the world throughout life (1). Transition is defined as a process of changing from one state or condition to another and it is considered as a pivotal concept in nursing (2). For nurses, the transition is a non-linear experience that shifts the person with skills, experiences, meanings, and expectations to another position (3).

Meleis’ theory of transition shows that transition occurring with life events requires a new response pattern and offers new strategies for coping with daily life experiences (2). Since transition is a phenomenon that varies in people with different experiences (4), numerous studies have introduced situation-specific transition theories for different populations based on Meleis’ theory to achieve more favorable nursing interventions (5, 6). In these theories, transition-specific concepts have been modified according to certain situations or populations (2). These theories focus on the patients’ general process of transition regardless of their specific situations. Different studies have evaluated the process of transition in specific populations and have introduced models to help further develop this theory (7).

According to a review of the literature, half of the nurses working in psychiatric wards bear excessive amounts of stress and emotional burnout (8, 9). Psychiatric nursing graduates face many challenges when entering the work setting. Transition programs can be influential as a potential way to help maintain and improve the mental health of staff (10). The results of a study by Schwartz et al. emphasized the transition process when mental health nurses move from a passive to an active stage; they regarded a safe workplace as a fundamental dimension of a successful transition (11). Few studies have examined the experience of transition to a mental health care role, most of which have focused on the nurses’ general transition from the university to clinical settings (12, 13) or on the situation-specific transition to special wards, such as intensive care units or emergency wards (14, 15). A few literature reviews have examined studies on nurses’ transition to psychiatric wards; some of the reviewed studies have been irrelevant (10) and some have merely examined the care experiences of nurses transitioning to psychiatric wards (11). Establishing a basis for future studies to further examine this issue is essential for creating a holistic perception of the transition to care roles (16).

There is a lack of qualitative studies on the nurses’ process of transition to psychiatric wards in Iran while there are many problems in this area. Qualitative studies allow researchers to gain access to participants’ inner experiences in the area in question. Therefore, the current study utilized a qualitative method. Moreover, the transition takes place following the nurses’ social interactions in real situations and it is regarded as a process by nature. Thus, the present study was conducted to explain the nurses’ transition to psychiatric wards based on the grounded theory (17).

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to explain the nurses’ process of transition to psychiatric wards.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This study examined the transition process of nurses in psychiatric departments using the grounded theory approach.

3.2. Participants

This study was conducted in the psychiatric wards of two referral hospitals in Mazandaran province, the north of Iran, and a psychiatric referral hospital in Tehran, Iran (18). The sampling began purposively and continued theoretically. Once the initial categories emerged, further participants were selected based on the degree to which they could contribute to the clarification of the emerging categories. The researcher used reminders to detect the ambiguities and gaps in the data and resolved them using the categories developed through theoretical sampling. This process continued until theoretical saturation reached or the emerging theory was fully developed (17, 18).

We held 27 interviews were with 27 psychiatric nurses (two head nurses, one supervisor, and 24 nurses), five of whom were selected purposively and the rest theoretically. The inclusion criteria consisted of being able to communicate, having the experience of a transition to psychiatric wards, having entered these wards as a nurse, and having full-shift work in these wards for at least three months. Sampling was carried out with maximum variations in terms of gender, education, years of service, type of ward, and hospital to collect in-depth and rich data (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 16 |

| Education | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 21 |

| Master’s degree | 6 |

| Ward | |

| Acute | 20 |

| Chronic | 5 |

| Pediatric | 2 |

| Hospital | |

| Zare, Sari | 12 |

| Yahyanejad, Babol | 5 |

| Razi, Tehran | 10 |

| Years of service | |

| ≤ 2 | 9 |

| 3 - 8 | 8 |

| 8 - 14 | 3 |

| 14 - 20 | 3 |

| ≥ 20 | 4 |

Participants’ Characteristics

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected initially with unstructured interviews, followed by semi-structured interviews. For this purpose, the researcher attended the ward, introduced herself, briefed the nurses on the study objectives, asked for their consent for participation in the study, and proceeded with the interviews. Given the heavy workload and the limited number of personnel in the ward, the researcher scheduled a specific time for the interviews and re-visited at the specified time. The interviews lasted 15 - 50 minutes.

The interviews began with a general open-ended question such as “What are your experiences of the first days of your work?”. Then, the interviews continued based on the discussed subjects using guiding and clarifying questions that helped reach the objectives, such as “What problems did you have?”, “How did you encounter your problems?”, or “How did you resolve these problems?”. As the interviews continued, more specific questions were posed in line with the emerging categories and the study objectives. The interviews were conducted individually in a quiet place at the participants’ workplaces and recorded with the participants’ consent. In the theoretical sampling stage, the interviews were conducted based on the analysis of the data obtained from targeted interviews and semi-structured memos written about the nurses’ insufficient readiness, the fear of patients, acquiring experiences as a way of caring for the patients and oneself, and the effective role of comprehensive support.

3.4. Data Analysis

Using Strauss and Corbin’s approach (2008), the data were analyzed in terms of concept and context; the processes were linked to the data analysis and the categories were combined while emphasizing constant comparison. The concepts that emerged in each interview were analyzed. The researcher transcribed and reviewed the interviews several times to extract the primary codes. As the interviews moved forward, the codes were compared to one another in terms of their mutual characteristics. The codes were classified into primary conceptual categories. The categories and subcategories were formed by integrating the mutual, overlapping themes, and comparing the new data with the previous data; memoing proved helpful in this stage. The nurses’ main concern in the transition to psychiatric wards was determined and conceptualized at the end of this step. In the second step, the data and concepts were then analyzed in terms of the context. The next step was dedicated to incorporating the process into the concept and analyzing the data. As memos were being written, categories were being reviewed, and theoretical sampling was being conducted, the context and process were gradually linked and the categories were revised. In the last step, the categories were integrated to develop a theory. In this step, the core variable was identified using the memos and after contemplating the data. The concepts were linked to the core category and the theory was developed once the core variable emerged; then, the rest of the categories were linked to it (17).

3.5. Data Rigor

The rigor of the study was evaluated using the criteria of validity, confirmability, reliability, and transferability (18). The researcher tried to be adequately sensitive to the participants with prolonged engagement; she obtained the data and performed the interviews by asking the later probing questions based on the participants’ previous answers without personal bias. Also, in the data analysis, she extracted the codes without personal bias. To increase the validity of the data, the researcher performed a constant comparative analysis during the entire process of data collection from nurses who had the experience of a transition to psychiatric wards. For the convergence of data with experiences, the primary codes were checked by the participants and we made corrections when necessary. To ensure the confirmability of the data, two qualitative researchers checked the codes and the categories emerged from the interviews. To ensure the transferability of the data, sampling was conducted with maximum variations in age, gender, education, and ward type.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted after being approved by the university’s ethics committee under code IR.TMU.REC.1394.169 and obtaining the hospitals’ permission. At the beginning of the sessions, the researcher briefed the participants on the study objectives and methods; she arranged a time and place for interviews with the willing participants. The interviews were recorded with participants’ consent and the researcher undertook to stop recording the interviews when it was requested by the participants. The participants were ensured of their right to withdraw from the study whenever they wished and the confidentiality of their data and names. The required permissions were obtained from the medical centers’ directors. Feedback was also presented to the relevant authorities in accordance with the results.

4. Results

The results are provided according to the algorithm used for data analysis. In the first phase, the analyzed concepts led to 45 primary categories and 13 final categories or concepts. According to the comparative analysis of the data and concepts at the end of this step, we identified concerns such as the fear of patients, stress of patient care, disappointment, mental preoccupation with the risk of getting ill, mental disturbances of work, and the lowered spirits as a result of the society’s negative attitude toward nurses and psychiatric wards as the nurses’ main problems in these wards. We categorized them as “all-around threats and insecurities”. The all-around nature of these threats and insecurities owed to their dimensions and origins as they came from patients, the society, the nurses’ own confusions, and the people around them.

The constant analysis and comparison of the data showed that most participants had felt fear of patients at the beginning of their work in the psychiatric ward, which was mainly due to the feeling of being harmed by patients. One of the female participants with 14 years of work experience at Razi Hospital in Tehran stated, “I was so afraid of patients that I said I won’t go to work any longer. The environment was very terrifying for me…” (Participant no. 15).

4.1. Data Analysis in Terms of Context

The researcher had to discover and explain the causes of the concern or the context in which the threats and insecurities occurred. The data analysis showed that threats appeared in the contexts of insufficient preparation in the university, irritability and aggressiveness of patients, resource limitations, and safety.

4.1.1. Insufficient Preparation at the University

The participants had not been sufficiently trained in the university for working in psychiatric wards. “When I entered the ward for the first time, it severely affected my spirit because the education they gave us at the school was such that we weren’t very involved with such patients.” (Participant no. 1).

4.1.2. Irritability and Aggressiveness of Patients

The irritability and aggressiveness of patients was a reason for the nurses’ stress and fear of patients. The nurses pointed out the risk of harm by psychiatric patients due to their aggressiveness. They deemed the patients a threat because of their characteristics; they worried and feared that they might harm them. “I was very frightened by the environment … I was so scared too scared because psychiatric patients behave differently and are often aggressive.” (Participant no. 16).

4.1.3. Resource Limitations and Safety

According to the nurses, the small number of personnel, the lack of security guards and equipment in psychiatric wards caused fear. They stated that a large number of patients and the small number of personnel and security guards in psychiatric wards increased their stress and fear. “I had stressed by the patients and the small number of the personnel … there were 30 patients … we had two nurses and two maintenance staff or one security guard for all 40 patients” (Participant no. 19).

4.2. Data Analysis in Terms of Processes

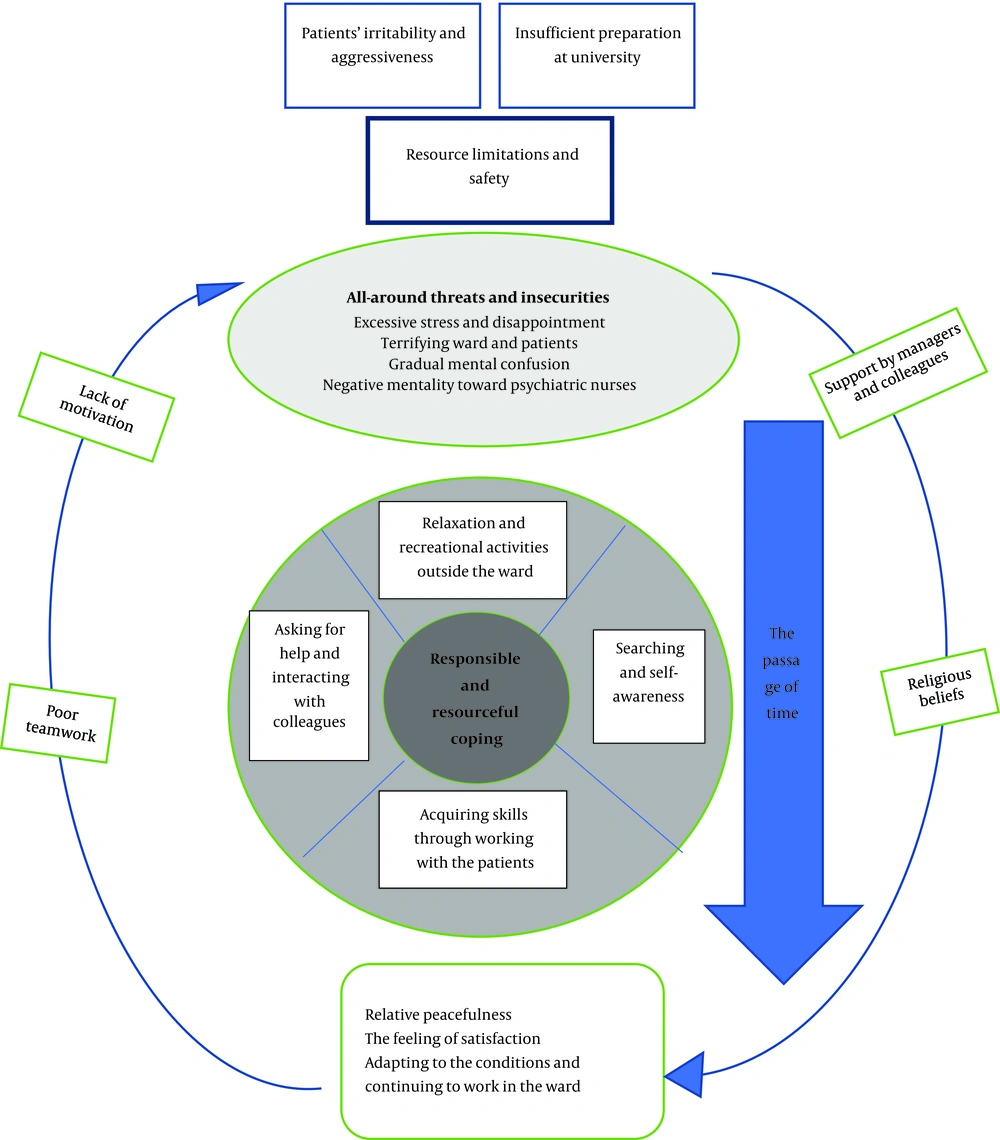

Processes were identified, including the nurses’ actions and reactions to threats and insecurities and their consequences (Figure 1). In general, nurses used strategies such as searching and self-awareness, relaxation and recreational activities outside the ward, asking for help and interacting with colleagues and learning and acquiring skills in the face of these threats and insecurities perceived in psychiatric wards.

4.2.1. Searching and Self-Awareness

The nurses tried to overcome threats and insecurities by acquiring information and raising their knowledge and awareness to reach self-awareness and obviate their fear of patients and their consequent anxiety. “I received information and attended classes about psychiatric medications and psychiatric illnesses … well, they were effective and finally decreased my fear” (Participant no. 21).

4.2.2. Learning and Acquiring Skills Through the Experience of Working with Patients

The participants tried to learn how to properly communicate with patients while working at the ward and gain experience; thus, they could reduce and control their concerns about the risk of being harmed by patients.

4.2.3. Relaxation and Recreational Activities Outside the Ward

The participants found that their personal time and recreational activities outside the workplace helped them better adapt to the situation at the ward.

A male participant with seven years of work experience in the psychiatric ward at Razi Hospital said, “I started planning more fun activities outside the hospital for myself and making greater use of my time. I do art, I paint, calligraphy, and the like.” (Participant no. 18).

4.2.4. Asking for Help and Interacting with Colleagues

The participants also tried to ask for help and support from their experienced colleagues and interact with them to better cope with the problems in the ward and reduce their stress. “I asked my (experienced) colleagues to tell me what to do or how to treat this particular patient. It was very helpful and decreased my stress” (Participant no. 11).

Using these strategies for dealing with all-around threats and insecurities, the nurses reached positive outcomes such as relative peace, feeling of satisfaction, adaptation with the ward conditions, and the continuation of their work.

According to the constant comparative analysis of the data in the previous steps, the review of memos, the nature of the problem and the nurses’ concerns, the ways they dealt with them, and their actions and reactions, the nurses were successful in coping with the main problems perceived in the transition to psychiatric wards, i.e. all-around threats and insecurities. The strategies used for coping with threats and insecurities included understanding the conditions of the ward and patients through searching and gathering information, gaining familiarity with patients, and learning and acquiring skills through the experience of working with patients. These efforts were personal, accountable, resourceful, and attentional in nature and implied responsible and resourceful coping. The nurses made efforts to actively cope with the psychological threats and insecurities they experienced when starting the work in psychiatric wards and thus tried to effectively handle the problem. They eventually passed this stage successfully without psychological harm; they began to feel satisfied and were relatively peaceful about working in these wards and they adapted to the conditions of the ward (Figure 1).

5. Discussion

The results showed that nurses were concerned about all-around threats and insecurities in their transition to their new roles in psychiatric wards. They used a variety of strategies such as learning and acquiring skills through the experience of working with patients, searching and self-awareness, asking for help and interacting with experienced colleagues to deal with the threats and insecurities, becoming satisfied and relatively peaceful, and adapting to the conditions of the ward.

The dimensions of the strategies used for dealing with these concerns in some respects were similar to the dimensions reported in other studies. For example, in a study, nurses were found to experience some degrees of tension in the form of anxiety during their stage of transition (12, 19-23). Given the different nature of psychiatric wards, the type of tension observed in the participants of this study differed from that observed in other wards in other studies (10, 24). Unlike other studies, the nurses’ fear and stress in this study were due to the risk of being harmed by patients, which is a risk specific to psychiatric wards. Moreover, the strategies used by the nurses to cope with these threats were different from those used by nurses transitioning to other wards.

The nurses in this study experienced concerns in the form of stress and fear of harm by patients during transition. However, St. Clair’s study (20) of the experiences of learned nurses in the process of transition showed negligence and errors in the performance of tasks during the process of gaining familiarity with special care as the most important concern of nurses. When beginning their professional careers in different hospital wards, new nursing graduates experience tensions in the form of stress and anxiety about their new responsibilities and independent decision-making, particularly in the evening and night shifts (12, 22, 23). The type of fear discussed by the participants in this study was, therefore, different from that discussed in other studies.

Another dimension of all-around threats and insecurities as the nurses’ major concern in this study was their preoccupation with the risk of getting ill after observing the patients’ symptoms and their gradual psychological confusion. The results obtained by Lewis-Pierre et al. showed that the nurses entering ICUs were preoccupied with the thought of how to best play their new roles and meet others’ expectations; they were anxious about whether their performance was appropriate (19). The nurses’ preoccupations are different in nature in psychiatric wards than in other wards because of the patients’ characteristics and symptoms; another reason is the nurses’ perception of their risk of developing these diseases.

People’s negative mentality about nurses working in psychiatric wards was another dimension of the threats and insecurities affecting nurses. Studies conducted by Procter et al. and Tingleff and Gilbert revealed that nurses were reluctant to work in psychiatry wards because of its numerous challenges, including the negative attitude toward psychiatric nurses, which had adverse effects on their spirits (10, 16). These findings are consistent with the present findings in terms of the unwillingness of nurses to work in psychiatric wards due to the negative mentality of people around them and its consequent lowered spirits and depression. Such mentality is apparently a feature of psychiatric wards that has not been reported for nurses’ transition to others wards (14, 19, 23).

In the face of all-around threats and insecurities, nurses try to reduce their mental stress and confusion and feel satisfied by raising their self-awareness and knowledge. Meleis explains that preparation, which basically deals with the acquisition of knowledge about transition-related events and management strategies, facilitates the transition and its lack impedes a successful transition (2). The results obtained by Lewis-Pierre et al. showed that new nursing graduates transitioning to their new roles in ICUs could reduce their main concern about their quality of performance and learning to adapt to these wards through the acquisition of knowledge on proper communication with patients who can show no reactions and patients requiring support, communication with the patients’ family and with their colleagues, drug management in ICUs, and the prioritization of the patients (19). The results obtained by Morphet et al. also showed that transition training programs are effective in the recruitment and retention of emergency nurses, the improvement of their job satisfaction, and the reduction of nurses’ burnout (14).

The prominent strategy used by nurses in this study during the stage of transition to the ward was responsible and resourceful coping with the all-around threats and insecurities. The Meleis’ transition theory also shows that transition occurring with life events requires a new response pattern and new strategies for adapting to daily life experiences (2).

People cope with stress in different ways. Coping refers to the process of managing the (internal or external) demands that are more difficult or beyond the individuals’ resources (25). In this study, the nurses tried to learn how to cope with threats by reflecting on their issues and increasing their self-awareness and skills. They gained this skill by increasing their information, knowledge, accountability, and positive evaluation and resolved their problems and achieved satisfaction and peace by adopting responsible and resourceful coping strategies. A study by Chang et al. showed that nurses using problem-oriented coping strategies were psychologically healthier than their peers who used emotion-oriented strategies (26). Ribeiro et al. found that emergency nurses mostly used problem-solving and reappraisal strategies for coping with different things (27). The present findings are also consistent with the results obtained by Senining and Gilchrist, who found that nurses in psychiatric wards used problem-solving, self-control, and positive reappraisal strategies to cope with their concerns about the patients’ unreliability (28). The results of some studies are inconsistent with the present findings; for example, some studies have found that nurses’ main strategy for reducing stress in different wards included restraining and avoidance strategies, including getting away from the stressful situation and preventing the expression of emotions (29-31). Meanwhile, the psychiatric nurses examined in a study by Abdulrahim mainly used problem-oriented strategies for coping with occupational stress (32).

Transition is a difficult period in all nurses’ work-life that necessitates the strong support of the family, colleagues, and managers (21). Nurses should be officially supported at least in the first six to nine months of beginning their work (33). Providing them with mentors is a useful strategy for support and retention (10). The results of this study also showed that interaction with colleagues to receive their help is an efficient strategy for reducing the nurses’ fear and stress. Participants’ experiences in Abedi et al.’s study showed that transition from the student role to the professional role does not necessarily take place in a supportive environment in Iran’s nursing system (34); however, this finding is inconsistent with the present findings, in which nurses stated that they had received the necessary support during their period of transition. The 12-year interval between the two studies suggests that nurses and managers have begun to pay more attention to supporting new colleagues in the wards during these 12 years.