1. Background

The cognitivist basis of moral judgment has not valued the role of the emotion in moral judgment (1-6), nevertheless, each moral experience is emotionally a priori perceived and cognitively posteriori assessed (7). Moral emotions are instantaneous reactions where the ego suddenly responds from its affective system to balance a just relationship with others and with its environment (4, 8), which is the emotive moral judgment (9-11).

The cognitive stage (4-6), the affective system (12-15), the model id, ego and, superego (16-18) stand foundation of the emotive moral judgment. The moral emotions depend on how the ego recognizes its inherent righteousness and evil (1, 12-18). The egos of other people have the role of moral judgment, the emotional relationship between the moral authority and the person is fundamental in the life of the individual (19-29).

The Oedipus parricide activates horror, a repugnant sensation and an urgent desire to ignore the insupportable perception (18, 30, 31). The results of the anguish of the id castration done by the superego as the moral conscience and the tensions between the anguish of the id done by the superego and the operations of the ego, they act as the guilt (18-21).

Pride encourages the person for the success achieved to everything that exalts human dignity (25, 28-30). Pride is a pleasant emotion, an agreeable self-evaluation (28-30). The self-conscious emotions make a positive or negative estimation to the ego of the individual, motivating a positive or negative reinforcement of behaviors (28-30).

The evolution of the individual in society implies less enjoyment, greater self-awareness of guilt (21). So, the habituation of the moral emotion can make any personal pleasant experience means to him/her an immense enjoyment, greater than in another person unaccustomed to that (29). Guilt and pride are primary motivators of moral judgment (12, 18, 27, 30), which establishes cognitive stages (4, 10). Therefore, the emotive moral judgment is a priori assessment charged with energy that impulses the action and a posteriori deliberation about if the action was correct. The emotive-cognitive stages are characterized by guilt and pride, as follows:

1.1. The Emotive Preconventional Level

The ego feels guilty or proud, egoistically seeking the pleasant energy of pride over guilt, without being aware of anything or anyone. This level is defined as stage one where punishment or reward is the stimulus of guilt or pride (12, 18). The stage two recognizes only an authority to whom the highest moral image is attributed, whose feedback signals approve or disapprove the ego’s actions (12, 13).

1.2. The Emotive Conventional Level

The ego feels pleasure to be within the conventional rules. In the stage three, the moral is established by group manifestations, which mark what right is (4). Here, the ego feels proud of belonging or guilty by rejecting (21). The stage four determines that social rules increase guilt in the ego and diminish pleasure (4, 21-24). Thus, pride in the ego stimulates the correct behavior (25, 29).

1.3. The Emotive Postconventional Level

In the stage five, the guilt is increased by means of the social rules (21-24), it implies a breakage of the emotions provoked by the disreputable image about individual realized by a social minority (25, 29). In the last stage six, the moral maxims imposed by the superego are corrected (21). The individual will seek a superior self-perception and assessment than previous in front of his/her self and the others (25, 29).

Some contemporary approaches intend to assess the incidence of emotions in moral performance (1, 12, 30). Two emotions that can be considered in moral judgment are guilt (12, 18) and pride (25, 30). The emotional moral competence is defined as a priori reaction charged with energy that impulses the action and a posteriori evaluation of whether this impulse was correct (12, 27, 30). Searching in the literature showed neither index nor guilt and pride linked emotion and cognition.

2. Objectives

The purpose of the present study was to theoretically and empirically validate the Emotive Moral Test (EMT) and its main Emotional Moral Competence Index (EMCI). In addition, to validate sub-indexes, guilt (Guilt-EMCSI), pride (Pride-EMCSI), and to demonstrate the correlation between them. Also, to study whether the age of the participants positively correlated with Pride-EMCSI and inversely correlated with Guilt-EMSCI.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

IN this study, 177 voluntary students were randomly selected in august, 2018, from the Superior Institute in Centla (Mexico), the confidence level was 95% and the margin of error was 5%. The inclusion criterion was an educational year of difference, from the first to the fourth, complying with the differentiated treatment (32). Here, 76% of the subjects were single, 70% were men and, the mean age was 24 years old. Moreover, 57 participants were allocated to the group one (mean age ± SD = 20.58 ± 4.11), 33 subjects to the group two (mean age ± SD = 22.06 ± 4.15), 52 subjects to the group three (mean age ± SD = 24.87 ± 7.45), and 35 subjects to the group four (mean age ± SD = 30.79 ± 7.97).

3.2. Instruments

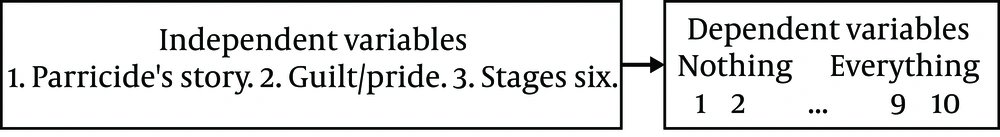

The EMT (Supplementary file Appendix 1) was used for its validation. The EMT integrates a parricide story named “the Juan’s story". It was explored in three iterations prior to the story reported. Also, it was developed to stimulate a horrific sensation in the participant, subsequently he/she was evaluated in six moral stages (5, 10). A comprehensive evaluation of the EMT items by a panel of twelve experts indicated that the CME items were adequate for the six stages. Figure 1 shows the EMT design. The dependent variable was established by the evaluation of the participants, who made the rating of the affirmations on an emotive scale from one to ten and, the three independent variables were: the parricide’s story, six stages and, guilt/pride.

The EMCI examines the reactive emotional consistency of guilt and pride. The EMCI evaluates the effects inter-subjects and its quantification was made by the partition of the sum of squares supplementary file (Appendix 2). The Guilt-EMCSI was quantified by adding the six arguments of the guilt and, pride-EMCSI by summing the six arguments of pride.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

I used SPSS-23 for analysis of variance, it was used to observe whether the treatments represented by the four groups of participants affected the EMCI. Additionally, the correlation analysis was applied to observe whether there were relationships between the EMCI, the sub-indexes, and the age and university years.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

All individuals voluntarily participated, researchers plighted that individual’s data remain confidential and all participants knew just about his/her data if he/she wanted to.

4. Results

The EMT and EMCI followed criteria based on the theory and the obtained data. The first criterion established the effect of participant groups on the EMCI (32) and the other six criteria established correlations between EMCI and six emotive cognitive stages deduced theoretically (12, 27-30).

4.1. Educationally Differentiated Observations at the University Level

The first validation criterion was achieved. Table 1 shows that the inter-subject effects of the participant groups on the EMCI (32) were not significant. The significance of the effect was very low and borderline (F = 0.962; P = 0.412). Furthermore, the effect size indicator was very questionable. The observed power was 0.26 and partial Eta squared was 0.016, so it can be told that just 26% of the individual’s variance was explained by the between-group variance.

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University year | 0.142 | 3 | 0.047 | 0.962 | 0.412 | 0.016 | 0.260 |

| Error | 8.506 | 173 | 0.049 | ||||

| Total | 24.914 | 177 | |||||

| Corrected Total | 8.648 | 176 |

4.2. Moral Emotion is the Motivator of Moral Judgment

The second criterion was achieved. This established that disagreeable emotion habituation was a factor of moral judgment (12, 29). People with higher educational level and greater age had less horror sensation. Table 2 shows the Horror-SI negatively correlates (-0.163) with the university year and the age of participants (-0.183).

4.3. Emotive Descending Correlation

The third criterion established that there was a descending emotive correlation, the higher stages were typical of the human maturation (5). Thus the horrific sensation should stimulate more first stages, typical of early ages and with less scholar experience than the last stages because of habituation of older people (12, 29). Table 2 indicates correlation values of the emotive stages and horror: three, four, five, and six (0.304, 0.280, 0.267, and 0.111) sorted from higher to lower. A contiguous increase of stages, one and two (0.287, 0.341), does not change trajectory and does not invalidate this criterion (33, 34).

4.4. Correlation Between Guilt and Horror

The fifth criterion was achieved. This criterion stated that the anguish of the parricide implied guilt (12, 18, 29) and the guilt would be decreasing (16). Table 3 shows that the guilt-EMCSI had a positive correlation with the horror-SI, negatively correlated with both university years and the age, while no correlation was shown regarding the pride-EMCSI.

4.5. Correlation Between Guilt and Age

This criterion was achieved. This criterion defined an inverse correlation between stages and guilt and pride (27). The guilt evolves as a human being grows and he/she contradicts values (22) and rules (12, 16). Thus guilt stimulates the first stages more than the last ones. Table 4 indicates that guilt-EMCSI correlates with the six stages in a descending way. Inversely, pride-EMCSI correlates with the six stages and gradually increases. There is a reverse in contiguous stages, however, these tendencies prevail and do not invalidate the EMT (33, 34).

4.6. Inverse Correlation Between Guilt, Pride and MCI Index

This last criterion was achieved. Pride and guilt had an inverse correlation with the EMCI (27). Table 5 demonstrates that the EMCI has a negative correlation with the guilt-EMCSI and a positive correlation with the pride-EMCSI. Furthermore, guilt-EMCSI and pride-EMCSI did not correlate; however, a negative value was found between them, which confirmed the antagonistic relationship between them.

5. Discussion

The present research showed that moral judgment has an emotional basis (10, 25), it extended the few studies on pride (29) and, an opposed relationship was empirically observed between pride and guilt (35). Additionally, guilt strongly and inversely correlates with the EMCI. The EMCI explicitly shows the inseparable emotive and cognitive relationship through two specific emotions, including guilt and pride.

The EMCI reinforces the dual theoretical precept of moral judgment (4, 34) and the pride is directly related to this competence. An applicable derivation of the findings is that the EMCI, the guilt-EMCSI and pride- EMCSI can be useful to unveil people who feel and reason ethically and, help to diagnose and prevent the moral anguish caused by the frustrated desire of wanting to do the right thing, which have terrible effects on health (36). Although more validation research is required. The present results suggest that the sub-indexes can be used to evaluate workers who commonly carry out assessments at a low morality level, as few studies have examined the way by which emotions affect organizational ethics.

The shown sub-indexes and index help to the idea that solid professional ethics has a positive relationship with the organizational practice and job satisfaction. In addition, it supports the diagnosis of people’s moral reasoning (37). Moral behaviors are positively related to well-being, while inversely, immoral behaviors are negatively related to mental disorder (38). Pride and guilt in moral judgment suggest that other emotions such as shame and indignation and, further learnings such as maximization and avoidance, self-conscious and non-self-conscious may do so as well (12, 39).

Most of the participants were male in the south-east of Mexico. This limits the generalizability of the results to populations in Mexico. More studies are needed, particularly in high school students, women and, employees.

5.1. Conclusions

A new way that values the emotive moral judgment was introduced. The theoretical and empirical validity of the EMT, its EMCI index, EMCSI-Guilt and EMCSI-pride sub-indexes were shown. Also, we showed that guilt and pride motivated moral judgment. Likewise, the guilt was a moral emotion opposed to pride, and pride had a favorable impact on moral judgment.

Finally, the importance of the validation procedure based on theoretical criteria was highlighted as follows: the moral emotion as a motivator, the moral emotional habituation, the descending relationship between the repulsion reaction and the moral stages, the inverse relationship between guilt and pride, and the rewarding moral emotion of success and pride favorably impacts the emotive moral judgment competence.