1. Introduction

Local relapse is considered the most severe risk for survival in breast cancer patients (1, 2). Experimental evidence suggests that surgery alters the tumor microenvironment. The formation of wound fluid (WF), as an expected outcome of surgical excision, promotes inflammatory wound healing responses that result in tumor progression (3-6). Some reports indicate that the tissue damage caused by cancer surgery favors cancer recurrence by providing a favorable niche (6). Further, it enhances cancer stem cells (7), ultimately impacting patient treatment outcomes unfavorably (8). Surgery, the mainstay of treatment for breast cancer patients, results in immediately releasing several inflammatory mediators in the WF. A release is a systemic event that can even activate tumor cells following cytokines and chemokines from the surgical site (9). WF components lead immune-controlled cancer cells to escape dormancy and convert into damaged cells (10-12). The tumor microenvironment includes immune cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) that interacts with tumor cells, resulting in WF formation within 24 h after surgery.

Recent reports suggest that wound healing is independent of tumor characteristics and depends primarily on the inflammatory response (12). Likewise, clinical studies on breast cancer patients suggest that early drainage improves life quality (8). Several studies have examined the effect of a combination of FBS and WF on breast cancer cell lines. For example, Wang et al. exposed MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines to 2% FBS, added to both WF (0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% WF) and medium (13). Ilenia and colleagues cultured MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cell lines in a complete or serum-free environment with 3% WF to assess WF's effect on stem cell-like phenotype induction (14). Ramolu et al. also cultured MCF-7 and HCC1937 breast cancer cell lines in DMEM with 10% FBS as a positive control and in DMEM with 5% WF as an experimental group to evaluate the WF effect on the breast cancer cell lines (3). Results obtained from these studies show that WF stimulates the proliferation of cancer cells. After surgery, the remaining tumor cells are exposed to WF secreted in the environment. Since most experiments have been done so far, they have been carried out only on cancer cell lines. We implemented a culture of human-derived micro-tumors on a tumor-on-chip microfluidic cell culture device. We re-created body conditions for the tumor cells that remained in the tumor bed 24 h after surgery. To this end, we used the WF alone and without culture medium (RPMI) for the experimental (Test) groups and RPMI with 10% FBS for the control groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

The specimens were obtained from 23 female patients between the age of 30 and 70 years. The patients were referred to Cancer Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences between 2/2018 and 10/2019 and were diagnosed with breast cancer in the second or third stages. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code NO. IR.SBMU.CRC.1398.158). The patients had no history of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and breast surgery. Their characteristics such as age, BMI, marital status, delivery status, and menopausal status are summarized in Table 1. Besides, Table 2 represents the tumor characteristics, including size, location, grade and molecular subtype.

| Patients | Age | BMI | Marital Status | Parietal Status | Menopausal Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 33 | 20.3 | Married | _ | Pre-menopause |

| S2 | 57 | 22.6 | Married | 4 | Post-menopause |

| S3 | 49 | 23 | Married | 2 | Pre=menopause |

| S4 | 74 | 21.1 | Married | 5 | Post-menopause |

| S5 | 43 | 25.5 | Married | 2 | Pre-menopause |

| S6 | 27 | 24.5 | Married | 1 | Pre-menopause |

| S7 | 28 | 17.3 | Single | _ | Pre-menopause |

| S8 | 72 | 33.4 | Married | 3 | Post-menopause |

| S9 | 40 | 23.2 | Married | 2 | Pre-menopause |

| S10 | 55 | 22.2 | Married | 5 | Post-menopause |

| S11 | 32 | 19.3 | Married | 2 | Pre-menopause |

| S12 | 49 | 24.7 | Married | _ | Pre-menopause |

| S13 | 60 | 23.3 | Married | 4 | Post-menopause |

| S14 | 53 | 21 | Married | 3 | Post-menopause |

| S15 | 48 | 25.6 | Married | 3 | Post-menopause |

| S16 | 41 | 20.9 | Married | 1 | Pre-menopause |

| S17 | 69 | 24 | Married | 4 | Post-menopause |

| S18 | 61 | 21.1 | Married | 3 | Post-menopause |

| S19 | 41 | 22 | Married | 2 | Pre-menopause |

| S20 | 39 | 19.2 | married | 1 | Pre-menopause |

| S21 | 50 | 23 | Married | 3 | Pre-menopause |

| S22 | 50 | 22.4 | Married | 2 | Post-menopause |

| S23 | 37 | 26 | Married | 1 | Pre-menopause |

| Patients | Tumor Size (cm) | Tumor Grade | HER2/ ER/ PR | Tumor Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 3.2 | II | + / -/ - | Left |

| S2 | 1 | II | -/ -/ - | Right |

| S3 | 5 | III | -/ +/+ | Right |

| S4 | 1.9 | II | -/ +/ + | Right |

| S5 | 3.5 | III | -/ +/ + | Left |

| S6 | 5 | III | +/ +/ + | Right |

| S7 | 4.5 | III | +/ +/ + | Right |

| S8 | 1 | II | -/ +/ - | Left |

| S9 | 1.6 | II | -/ +/ + | Right |

| s10 | 4.5 | III | -/ +/ + | Left |

| s11 | 5 | III | +/ -/- | Left |

| s12 | 1.5 | II | +/ +/ + | Right |

| s13 | 3.3 | III | -/ +/ + | Left |

| s14 | 1 | II | +/ +/ + | Left |

| S15 | 1.5 | II | -/ +/ + | Left |

| s16 | 2.5 | III | +/ -/ - | Left |

| s17 | 3.5 | III | +/ +/ + | Right |

| S18 | 3 | III | -/ +/ + | Left |

| s19 | 4.3 | III | -/ +/ + | Right |

| s20 | 2 | II | +/ +/ + | Left |

| s21 | 5 | III | +/ -/ - | Right |

| s22 | 4.3 | III | -/ +/ + | Right |

| s23 | 3.7 | III | -/ +/ + | Left |

2.1.1. Patient Samples

Tissue samples were taken from patients who underwent breast surgery according to the Cancer Research Center protocols at Shohadaye Tajrish hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. For each case, the fresh intraoperative sample was sent to the pathology laboratory during the operation. Further, about 3 grams of fresh sample in a 15 mL Eppendorf sterile tube containing RPMI 1640 was placed on ice and sent to the cell culture laboratory within 30 min. The surgeon used the suction drainage to remove the WF 24 h later. The WF sample was then sent to the laboratory in a 15 mL sterile Eppendorf tube. Under sterile conditions, the WF was centrifuged and filtered using 0.22 and 0.45 micrometers filters. The filtered WF was then stored in sterile micro tubes at -80 °C and used to treat the samples every 24 h.

2.2. Spheroid Preparation

Fresh samples in RPMI were kept on ice until delivery and then mechanically separated using scalp and forceps in a 10 cm sterile glass container containing 3 mL RPMI + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin/streptomycin, under aseptic conditions. For enzymatic dissociation, collagenase type I (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and 10X PBS were added to minced tissues and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. Dissociated samples were suspended in 20 mL RPMI + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The suspensions passed through a series of 100/40 μm strainer filters to generate 40 to 100 µm spheroid fractions; this being the optimal size for the culture of the tumor spheroid fractions in the microfluidic device. The spheroid fractions were re-suspended in fresh RPMI and pelleted. Tumor spheroids were mixed with type I rat tail collagen (Corning Co, MA) at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL and pH 7 - 7.5, according to the published protocol (15).

2.3. Microfluidic Cell Culture

The mixture of tumor spheroids and type I rat tail collagen was injected into the central channels of the microfluidic devices that had been designed and fabricated by AIM BIOTECH (company address) (https://www.aimbiotech.com) (16). Spheroids from each sample were seeded in at least two devices, based on the number of spheroids obtained. Two devices served as the control (to treatment by RPMI+FBS), while two served as the test (WF treatment). The spheroid-containing devices were incubated in a sterile humidity chamber at 37 °C for 30 min; the medium (RPMI+FBS) was then injected into the channels to hydrate the spheroids. After 24 h, the conditioned medium in the control channels was replaced by a fresh medium (i.e., RPMI+10%FBS+1%penicillin/streptomycin), conditioned medium in the test channels was removed and replaced with filtered WF from the patient. From day 2 to 6 (17), the medium was removed from each channel, and a fresh medium was added daily (RPMI/FBS was added in control and WF in test channels).

2.4. Live/Dead Staining

On the sixth day, Live/Dead assays were performed on spheroids using Nexcelom ViaStain™ AO/PI staining solution (Nexcelom, CS2-0106) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In short, equal volumes of the stain and PBS were added to the empty media channels (media channels after removing media) of the microfluidic devices and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes in the dark.

2.5. Optical and Immunofluorescence Imaging and Data Analysis

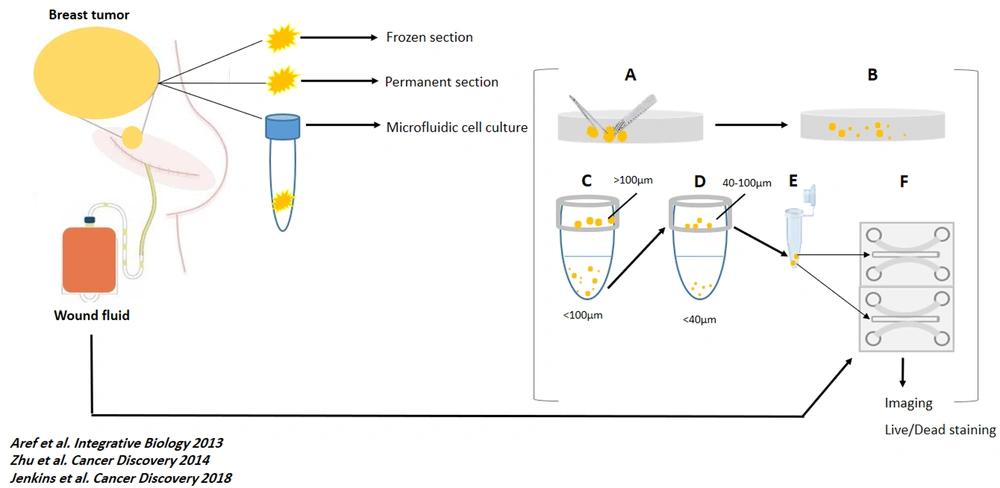

All the spheroids on each device were monitored, and optical imaging was performed every 24 hours for six days (using the Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with the Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera and using NIS-Elements software). Fluorescent images were also captured using the same microscope after live and dead staining. Spheroids were assessed in all channels for live and dead fluorescent stains. The software performed image analysis. The total area of live (green) cells stained with Acridine orange was measured against dead (red) cells stained with Propidium Iodide. Figure 1 shows a summary of the methods in this study (workflow).

Work flow of the study. At day 0, tumor specimens were removed, sent to pathology lab for preparing frozen and permanent section and, to cell culture lab. Also, Suction drains were placed at the site of the surgery. (A and B). The samples were mechanically and enzymatically dissociated, respectively. (C and D) The dissociated specimens were filtered by 100 µm and 40 µm cell strainers. (E) 40 - 100 µm spheroids were mixed with collagen, on ice. (F) The mixed gel and spheroids were injected to the central channel of the chips. At day 1, 24h-wound fluids of the patients were centrifuged, filtered, and injected to the media channels of the ‘’Test’’ chambers. Also, RPMI was injected to the media channels of the ‘’Control’’ chambers. At day 0 to day 6, optical imaging was performed and, WFs and RPMI were replaced with new media. At day 6, Live/Dead staining and fluorescent imaging were performed. For each sample, 3 ‘’test’’ and 3 ‘’control’’ chambers were loaded with specimens and media.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

After examining the normal distribution of the data using a normality test, comparisons between two groups (Live-WF/ Dead-WF and Live RPMI/Dead RPMI) were made using a paired t-test. The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad/Prism (v7.0) Software. Mean ± standard deviation is presented in all charts.

3. Results

3.1. Optical Imaging Analysis

From day zero to six, we monitored the images of all seeded spheroids using optical microscope imaging. Spheroids obtained from each sample grew in both WF and RPMI over time. Their size increased, but no substantial qualitative difference was observed among the samples seeded on 23 devices. Sample n. 18 (S18) spheroid preparation and cell culture method were similar to the other samples, yet it resulted in a different outcome. S18 was resected from the right breast of a 61-year-old woman with three previous pregnancies. The tumor was measured 3cm and tested as the ER+, PR+, HER-2 and grade III tumors.

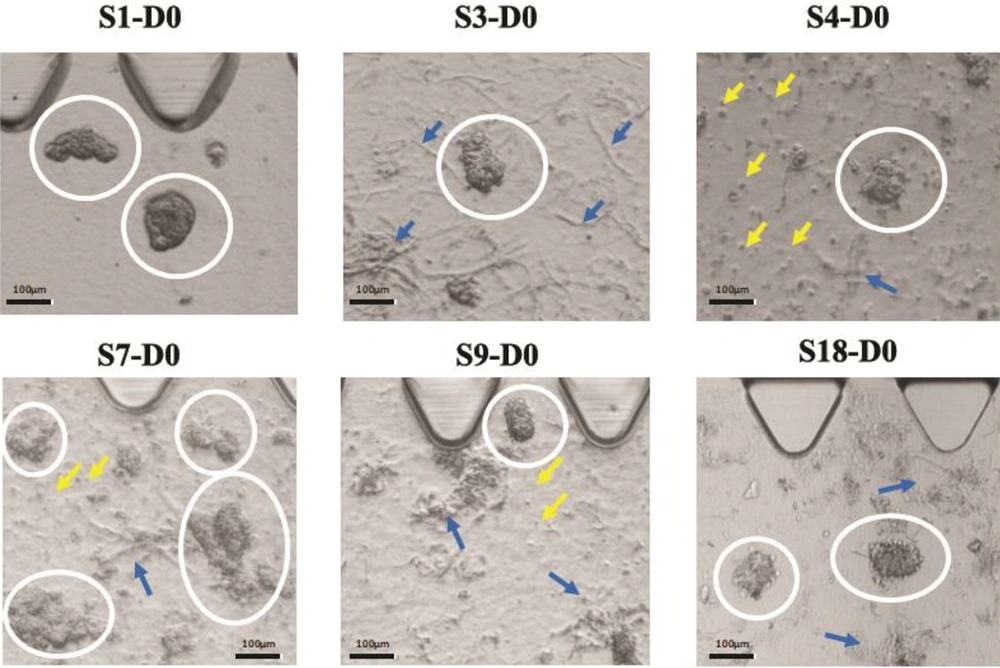

We found that breast tumors have different characteristics in terms of stiffness, cell density, and yield of spheroid production. In this regard, we noted that the samples were different in terms of cell density level and ECM density on day zero. Further, some samples formed single cells in spheroid preparation due to very low tumor density. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of our observations.

Different cell and ECM density are shown in six different tumors. In these images, white circles encompass tumor spheroids, yellow arrows point to single cells, and blue arrows point to the ECM. S1 has a high spheroid density but has no ECM and no single cell. S4 shows low ECM density, but a high number of single cells. S7 depicts high spheroid and ECM density, but a low to a moderate number of single cells. S3 and S18 both have no single cell but have moderate ECM densities. S9 shows moderate density ECM, but it depicts a low number of single cells.

3.2. The Proliferative Effect of WF on Live/Dead Staining

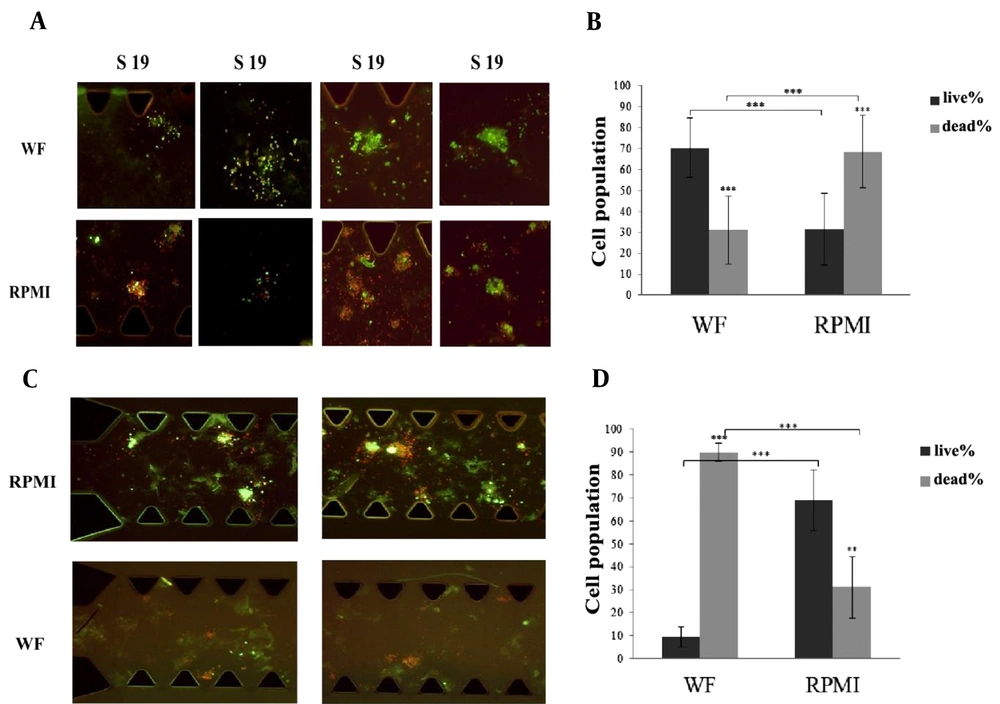

AO/PI staining was used to differentiate between live and dead cells in the spheroids on day 6. We found that in 22 out of 23 samples, the percentage of live cells treated with WF was significantly higher than in RPMI-treated samples. Pictures of WF and RPMI-treated spheroids derived from S11, S14, S19 and S22 samples are presented in Figure 3A. The red color indicates dead cells, while the green fluorescence indicates live cells.

(A) Some images from WF-treated and RPMI-treated spheroids belong to S11, S14, S19, S22 have been shown here. All the pictures were taken at Day 6 and the spheroids were stained by AO/PI (live/dead staining solution). Red color shows dead cells and green color shows live cells. (B) The percentage of the live cells under WF treatment is significantly more than the live cells under RPMI treatment. The graph shows the results from 22 samples. Dark gray column shows the percentage of the live cells and light gray column shows the percentage of the dead cells. (C) Wound fluid treated spheroids compared with RPMI treated spheroids in microfluidic devices. Spheroids were derived from reported case (S18). All the pictures were taken at Day 6 and the spheroids were stained by AO/PI (live/dead staining solution). Red color shows dead cells and green color shows live cells. (D) The percentage of the live cells under RPMI treatment is significantly more than the live cells under wound fluid treatment. Dark gray column shows the percentage of the live cells and light gray column shows the percentage of the dead cells. scale bars show 100 µm. (RPMI-treated spheroids are control samples and WF-treated spheroids are Test samples). AO/PI: Acridine Orange/ Propidium Iodide. WF: wound fluid.

The graph in Figure 3B shows the results of live/dead staining analysis on day 6. The percentage of live and dead cells in WF-treated spheroids from 22 samples was 70.33% ± 14 and 30.88% ± 16.2 respectively (P = 4.24E-17); in RPMI-treated spheroids, the frequency of live cells decreased to 31.6% ± 17.1, and that of dead cells increased to 68.59% ± 17.2 (P = 1.44E-12). Further, in these 22 samples, there was a considerable increase in cell viability in WF-treated spheroids compared to medium-treated spheroids (P = 3.97E-16). The diagram shows the summary results of the 22 samples.

As Figure 3C and D represent, the results obtained from S18 displayed an opposite pattern compared to the other 22 samples. The percentage of live and dead cells within WF-treated spheroids was 9.64% ± 4.29 and 89.78% ± 4.09 (P = 2.29E-10), whereas, in the case of medium-treated spheroids, the proportions of live and dead cells were 68.89% ± 13.31 and 31.1% ± 13.31 (P = 0.0010). Also, in S18, a significant increase in cell viability was observed in medium-treated spheroids compared to WF-treated spheroids (P = 0.00013). Further, a comparison between the frequency of live cells in WF-treated spheroids obtained from 22 samples and S18 revealed a significant difference: the number of viable cells after treatment with WF in the 22 samples is much higher than in S18 (P = 6.8E-15).

4. Discussion

The association between the risk of breast cancer relapse and surgery has already been investigated, and various theories have been proposed to explain the underlying mechanisms of stimulation and acceleration of tumor formation after surgery (6, 7). Some studies have deployed cancer cell lines and used a combination of conditioned medium supplemented with WF to investigate the effect of surgery secreted WF on tumor cells in the tumor bed. In this study, we mimicked a tumor microenvironment in-vitro in a 3D cell culture system. The device contained all cells typically present in the tumor, and collagen was applied as ECM. In this model, we also used only the secreted WF without any additional. It is widely accepted that the transition from a 2D to a 3D cell culture provides an in-vivo imitation of the biological processes commonly occurring inside the body, such as cell survival, differentiation, migration and protein expression (18-20). Microfluidics is a promising platform that provides an opportunity to answer various questions in cancer research accurately. We used a microfluidic device, which was suitable for the culture of human-derived-tumor spheroids (15, 16, 21). Although previous in-vitro studies reported WF proliferative effects on cancer cells, we report an unexpected and reverse observation in our findings for one specimen (Sample No.18). Data analysis showed that in this case (S18), the percentage of dead cells was higher in WF-treated cells than in RPMI-treated cells, differently from what was observed in other samples. Wang et al. treated MCF7, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines with WFs collected from 72 patients with breast cancer or benign disease to investigate the WF impact on breast cancer cell lines. They assessed proliferation and motility in treated cells and quantitatively analyzed WFs composition. Their findings indicate that surgery-induced WF boosts cell proliferation and migration (13). Ilenia and colleagues assessed the effectiveness of WF at inducing a stem cell-like phenotype. They treated six different breast cancer cell lines with 24h-WFs, obtained from breast cancer patients after surgery and found that WF promotes a stem-like phenotype upon activation of STAT3 (14). In another study, Ramolu and colleagues assessed WF effects on MCF7 and HCC1937 cell lines and revealed that WF stimulates cancer cell proliferation (3). Curigliano et al. have quantified the proliferative factors secreted during the wound healing process after surgery, including fibroblast growth factors, vascular endothelium growth factor, and transforming growth factor-beta (22). Our findings obtained from the majority of the samples analyzed support these previous investigations.

We noted that one sample displayed the opposite results (23). In oncology, precision medicine refers to an individualized treatment regimen based on each patient’s biological and pathological characteristics. Factors such as body mass index, breast density, family history, genetics and molecular subtype of the tumor are all involved in selecting the most appropriate treatment modality (24). Based on our observations, the spheroids under RPMI or WF treatment grew from day zero to day six. We also witnessed no phenotypic difference between S18 and other specimens in this regard. Besides, we found that the density of ECM and cells varies in different samples. It has already been reported that the behavior of cells in a single tumor might differ. Inter-tumor and intra-tumor heterogeneity of breast cancer, which in turn depends on variations among different individuals and different parts of the tumor, alters the cancer equation and its treatment (25). Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have self-renewal ability and differentiate into other cell types within a tumor (26, 27). They interact with their niche and produce factors that promote tumor invasion and metastasis (28, 29). The density of CSCs could be involved in the heterogenic migration of different clones in one single tumor. In addition to the heterogeneity of cancer cells within the tumor, other cell types recruited by cancer cells can also play a crucial role in tumor progression (30). In most solid tumors, macrophages represent up to half of the tumor mass (31, 32). Several distinct populations of tumor-related macrophages (TAM) are found during tumor development, often displaying phenotypes of M1 and or M2 (33). In many solid tumors, such as breast tumors, TAMs acquire the M2 phenotype, promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis (34). In addition to the type of cells involved in cancer cell migration, high cell density enhances tumor migration and metastasis due to increased matrix metallopeptidases (MMPs) expression (35). The cancer-related ECM actively contributes to tumor progression (36, 37). It has been shown that normal mammary epithelial cells are driven toward malignancy by increasing stiffness of the matrix (38). Increased ECM density causes MMPs-dependent and independent migration of cancer cells. ECM architecture itself can impact migration patterns. Increased collagen fiber concentrations are associated with mass cell migration due to the activity of MMPs (39), which leads to collective cancer cell invasion (40-42). We did not characterize the chemical composition of the WFs and did not specify the characteristics of living and dead cells. Therefore, S18 results could be related to WF compositions, including the presence of inhibitory factors. The different cellular composition of the spheroids can also have probably promoted WF induced apoptosis. To further prove this hypothesis, we recommend confirming the results by further experiments, including a higher number of specimens with similar conditions. The presence and amount of regulatory/inhibitory factors in WF and spheroids should also be identified and measured.

4.1. Conclusions

Here we report data from the 3D microfluidic culture of human-derived breast tumor spheroids. We analyzed 23 samples subjected to RPMI and WF treatments and observed that the increase in spheroid size was comparable in all samples throughout the six-day culture period. The results of the live/dead staining assay on day six showed that 22 of 23 specimens had similar results, with the percentage of live cells in the spheroids treated with WF being significantly higher than the control spheroids exposed to RPMI. In one case, however, we observed that the results were different since higher frequencies of live cells were noted amongst the spheroids treated with RPMI than those subjected to WF treatment. This 3D model study has advantages over conventional 2D in-vitro studies as it enables mimicking the TME. We monitored the cells daily and assessed the number of live and dead cells using imaging techniques. Our findings show that most patients with breast cancer benefit from surgical wound healing. However, removal of the surgical-induced serum may not be a method of inhibiting the tumor in all patients. We recommend that precision molecular medicine approaches be implemented to identify diagnostic biomarkers. Molecular diagnostic tests may help determine whether WF removal is beneficial (or not) on a case-by-case basis.