Introduction

Methamphetamine (N-methyl-1-phenylpropan-2-amine or METH) is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant and frequently used illegal. In tablet form (Desoxyn®), it was used to treat psychophysiological disorders such as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and obesity and narcolepsy in the 1940s (1). METH is a lipophilic cationic molecule that can cross the blood-brain barrier and exert neurotoxic effects on the CNS (2, 3). Studies in human addicts have revealed that repeated exposure to amphetamines can induce degenerative changes in dopaminergic and serotonergic axons (4). Different hypotheses about the mechanism responsible for METH-induced neurotoxicity have been suggested (5, 6). METH penetrates the neuron and displays both dopamine and serotonin in the vesicles, which led to the release of a large amount of them into the synaptic cleft (2). It can enter the intracellular organelles such as mitochondria and vesicles and alters the electrochemical gradient and enzyme activity (7). Dopamine auto-oxidation, synthesis and metabolism generate reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl superoxide and nitrogen radicals (8). It has been further shown that the generation of reactive radicals is the leading cause of mitochondrial dysfunction, decreased energy metabolism and apoptosis (9). Inhibition of electron transport chain, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis all play a critical role in METH induced neurotoxicity (10). There is no standard medical treatment for METH’s neurotoxic effects (1).

Cinnamaldehyde (CA) is the most important organic compound that is present in the essential oil from the stem bark of Cinnamomum cassia and gives its flavor and odor (11). The therapeutic effects of cinnamon are mainly attributed to its cinnamaldehyde derivatives, cinnamyl and eugenol. Various biological activities are related to CA include: antidiabetic, antifungal, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial (12). In addition, it has been reported that cinnamaldehyde has activities against neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases (13-15). In addition, some reports have shown that trans-cinnamaldehyde (TCA) has potent anti-inflammatory activity in the central nervous system (16). The present study was designed to examine the neuroprotective effect of TCA on METH-induced cytotoxicity.

Experimental

Materials

RPMI 1640 medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Invitrogen. 3 (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT), propidium iodide (PI) and fluorescent probe 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) were provided from Sigma Chemical Co.TCA was prepared from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co, Ltd.

Cell Culture

PC12 cells were cultured in RPMI medium (Bioidea, Iran) containing 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were maintained in a humid incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Cell Viability

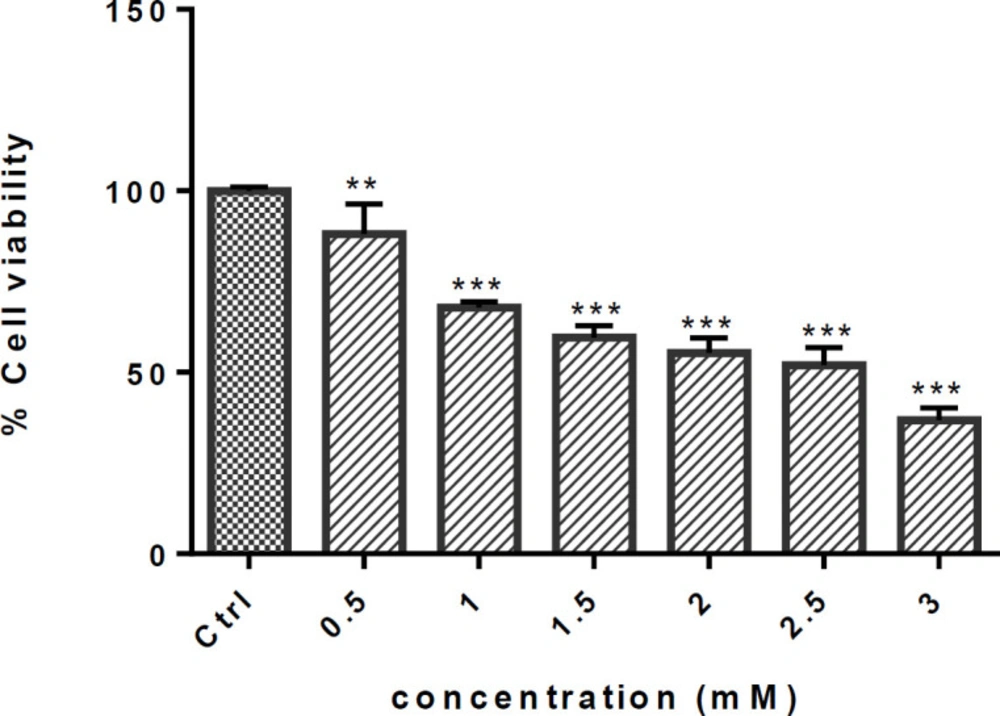

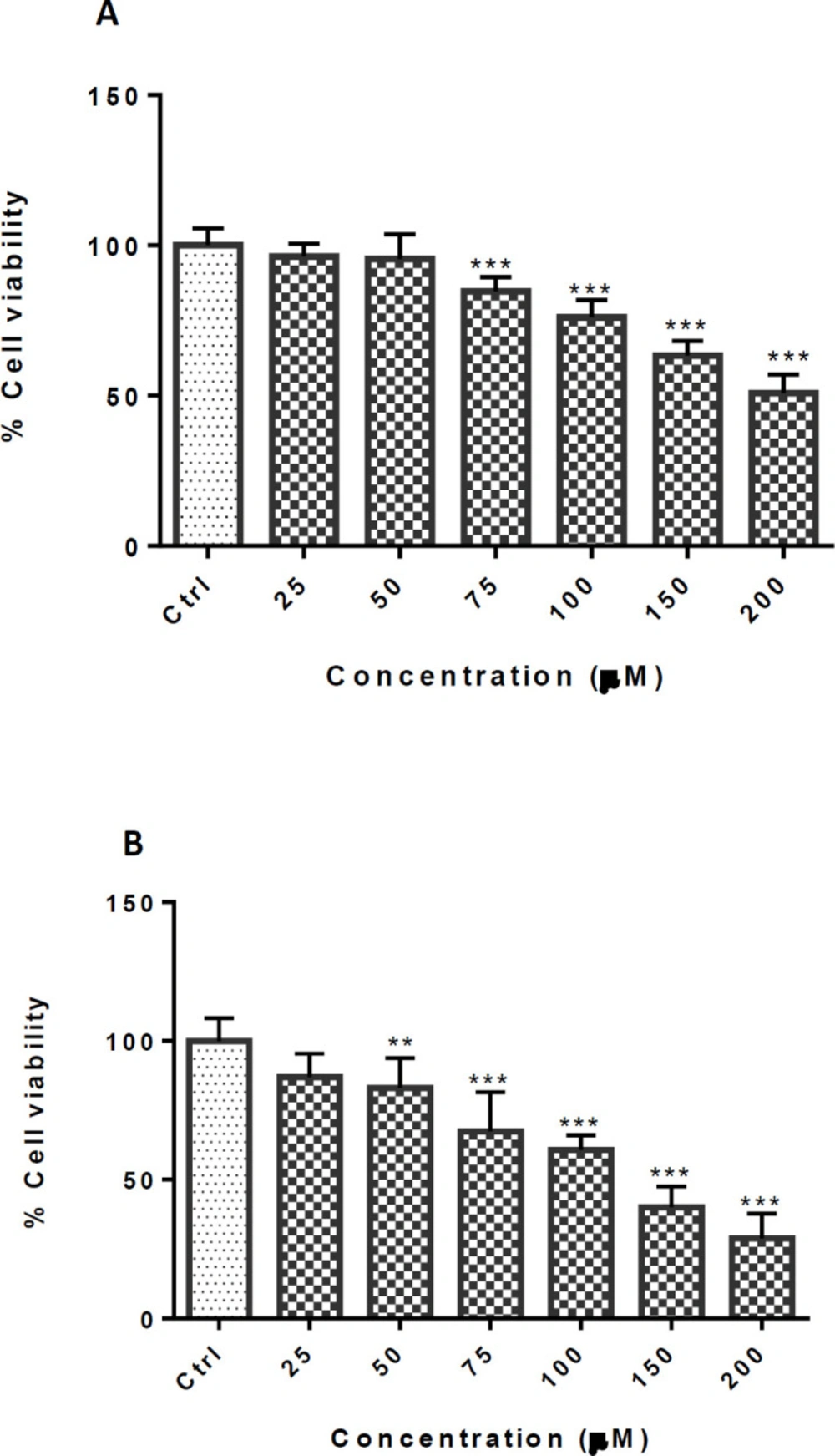

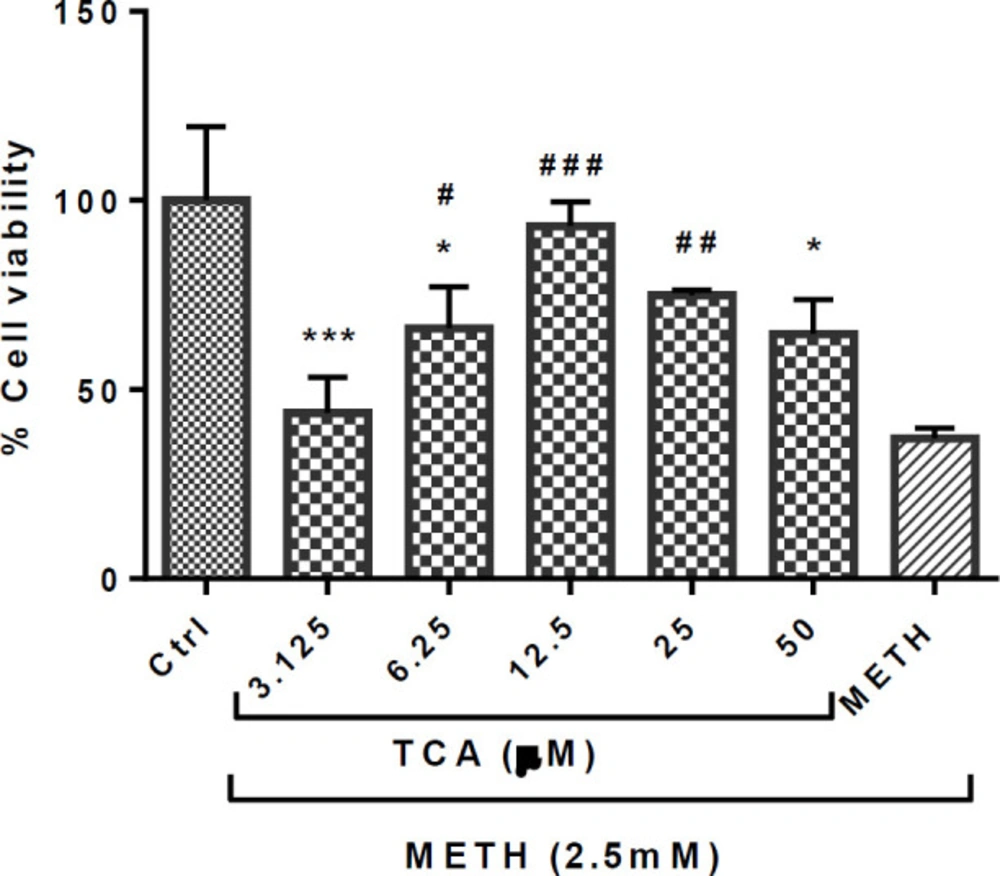

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol- 2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric assay was used to measure cellular viability and activation (17). In brief, PC12 cells were cultured in a 96-well microplate at a density of 5000 cells/well. To determine an approperiate concentrations, the cells were incubated with a fresh medium containing 0, 0.5,1, 1.5, 2, 2.5 and 3 mM of METH or 0, 25, 50, 75 100, 150 and 200 µM of TCA for 24 h. At the next step, cells were exposed to selected concentrations of TCA (3.125, 6.25, 15, 30 and 50 µM) for 24 h. Then METH at a final concentration of 2.5 mM was added to each well. After incubation for 24 hours, MTT solution at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL was added to the well. Then, the media was removed, and the formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). The absorbance of the purple solution was measured at 545 nm (630 nm as a reference) in an ELISA reader (Start Fax-2100, UK).

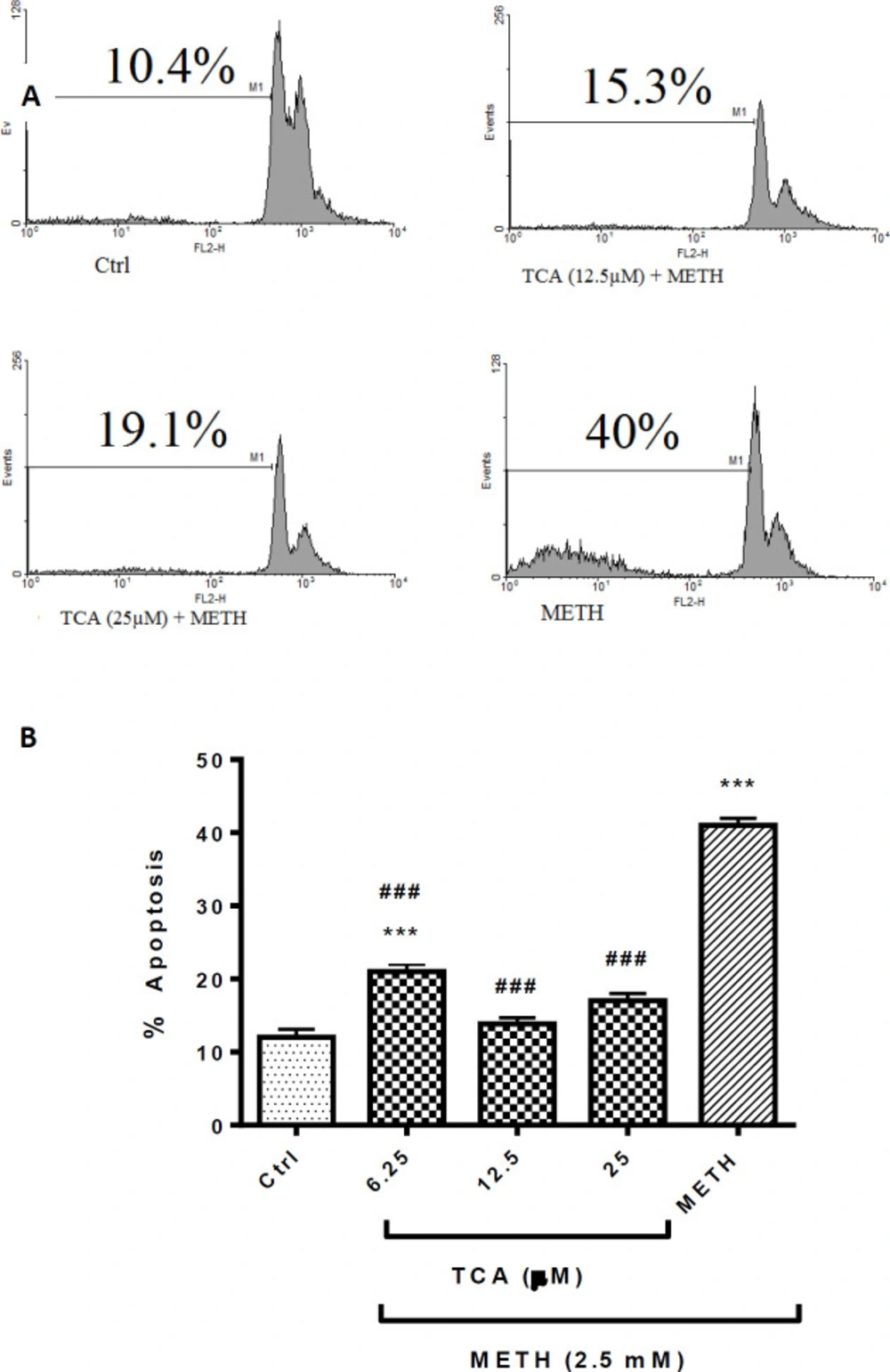

PI staining

The apoptotic effect was detected by PI staining, which determines apoptotic cells in the sub-G1 peak on the DNA content histogram (18, 19). Briefly, PC12 cells were seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well in a 12-well plate. Then TCA (12.5 and 25 µM) and METH (2.5 mM) were added to each well at two (2) consecutive 24 h periods, respectively. After then, suspensions of single cells were prepared by trypsinization and washed twice with cold PBS. The pellet cells were resuspended in PBS containing 50 μg/mL PI and 150 U/mL RNAse for 45 minutes at 37 ºC. The treated cells were then subjected to FACS flow cytometry analysis (20).

Measurement of intracellular ROS

The 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH2-DA) is a cell-permeable fluorimetric probe for detecting reactive oxygen (19). Upon reaction of DCFH with ROS, the highly fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF) is produced. As explained before, PC12 cells were treated with different concentrations of TCA and METH. On the last day of the experiment, the medium was replaced with RPMI containing 10 µM of DCFH-DA and the cells were incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The intensity of fluorescence from the DCF was measured by Partec TM cytometry (Germany) (excitation wavelength 480 nm; emission wavelength 530 nm) (21).

Reduced glutathione (GSH) assay

GSH was measured via the formation of yellow color in the presence of DTNB [5,5’-di thiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)]. Briefly, the day after the final treatment, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then treated with 5% trichloroacetic acid incubated at 37 ºC for 30 min (22). After centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was mixed again with 1 mL of a reaction mixture containing 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.6 mM DTNB at room temperature for 5 min. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 412 nm using a spectrophotometer (23).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer was performed to compare the results. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Effects on cell viability

Exposure to METH significantly decreased the cell viability at all concentrations in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Figure 1. Cell viability (expressed as the percentage to the control) reduced by 50% when exposed to 2.5 mM METH (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

In order to assess the nontoxic cinnamaldehyde concentration, the cells were treated with different concentrations (0-200 µM) for 24 and 48 h. There were no significant differences between the group that received TCA at 25 and 50 µM at 24 h exposure and 25 µM at 48 h exposure, compared with the control group. The IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) was calculated at 200 µM and 125 µM after 24 and 48 h exposure, respectively (Figure 2). According to the results, the protective effect of TCA at a concentration below 50 µM was evaluated against METH at a concentration of 2.5 mM.

The results showed a significant increase in the cell viability of cells pretreated with TCA (6.25, 12.5 and 25 µM), compared with the METH group (P < 0.05, P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively), as shown in Figure 3. However, TCA only at 12.5 and 25 µM enhanced the PC12 proliferation to return to a normal level.

Effect of TCA on METH-induced apoptosis

Quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells was measured with PI staining. Percentage of apoptotic cells increased to approximately 30% after 24 h incubation with METH (2.5 mM) over control (P < 0.001). Pretreatment of cells with 6.25, 12.5 or 25 µM of TCA significantly decreased the sub-G1 peak in flow cytometry histogram to 24.7% and 20.9%, respectively, in comparison with the METH group (P < 0.001) (Figure 4). There were no significant differences between TCA at 12.5 or 25 µM+METH and the control group.

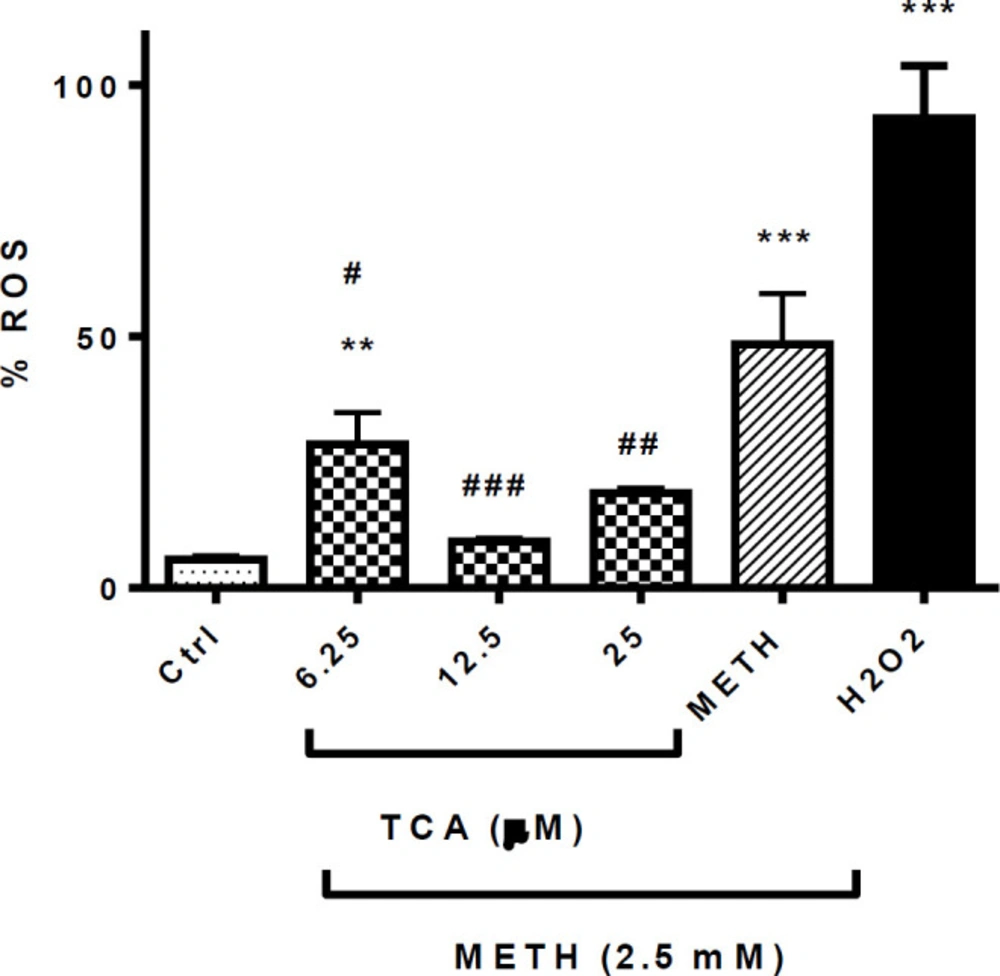

Effect of TCA on METH-induced ROS production

After 24 h of exposure, METH and H2O2 significantly increased ROS generation in comparison to control (P < 0.001). Pretreatment with 6.25, 12.5 or 25 µM of TCA significantly decreased the level of intracellular ROS in comparison with the METH group (P < 0.001, P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 5). However, exposure to the lowest concentration did not reduce the ROS to the normal level.

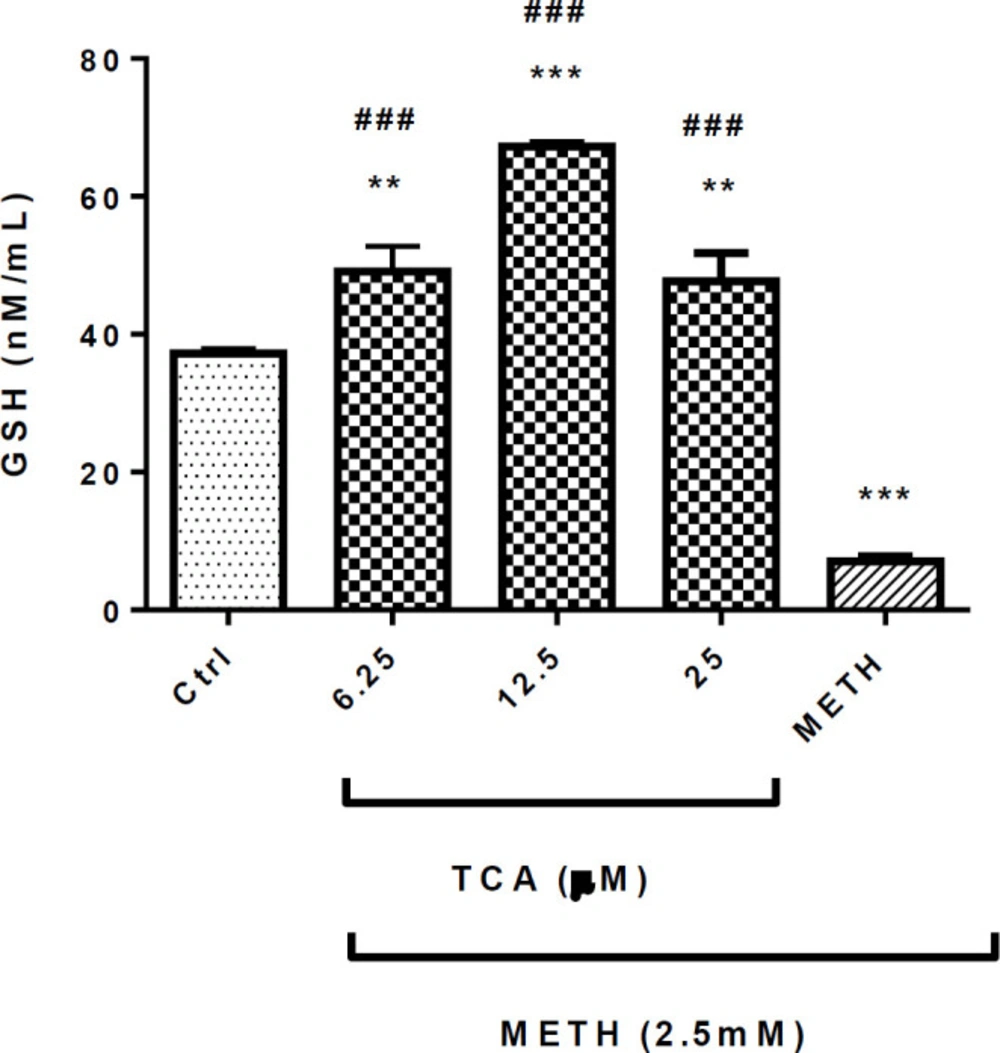

Effect of TCA on METH-decreased GSH level

METH (2.5 mM) significantly decreased the GSH level in comparison with the control group (P < 0.001). Pretreatment of cells with 6.25, 12.5 or 25 µM of TCA significantly increased the content of GSH (P < 0.001) in comparison with the METH group (Figure 6).

Discussion

The current study demonstrated for the first time that TCA, extracted from cinnamon, exerts significant neuroprotective effects against METH-induced cytotoxicity by inhibiting apoptotic DNA fragmentation and ROS generation and increasing glutathione levels in PC12 cells. Continued METH abuse is widely believed to cause serotonergic and dopaminergic neuronal injury. The effects of abuse of METH include memory problems, aggression, psychotic and behavioral abnormalities (9, 24). Evidence suggests that multiple molecular and cellular mechanisms are involved in METH-induced CNS toxicity, such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, excitotoxicity and inflammatory responses (25). Previous studies indicated that exposure to METH at doses greater than 2mM might result in decreased PC12 cell viability (26, 27). Our data showed that METH-induced a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability, while TCA suppressed the cytotoxicity at the concentrations less-than-or-equal-to 25 µM.

Both the in-vivo and in-vitro experimental findings indicated that cell apoptosis has a key role in METH neurotoxicity. They showed that it could be mediated by activation of the effector caspases 3, 9 and 11 and downregulation of Bcl-2/Bax expression (28-32). In this study, the quantitative analysis of apoptosis revealed a significantly higher rate of PC12 cell death after treatment with METH that was abolished by TCA pretreatment. Pretreatment with cinnamaldehyde (5, 10 and 20 μM) Could remarkably increase the cell viability and decrease the apoptosis by suppressing cytochrome c release, reducing the activity of caspase 3 and 9 in PC12 cells treated with glutamate. Exposure to CA also attenuated the glutamate-induced oxidative stress with decreased ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) production and increased GSH level, which was in agreement with our study (33). The amount of GSH significantly decreased in TCA+METH treated group. In addition, the generation of ROS was inhibited by TCA treatment. The animal studies result supports the beneficial effects of cinnamaldehyde on brain damage and oxidative stress induced by a high-fat diet. The HFD increased MDA in serum and the brain and NO level in the cerebellum that was prevented by CA (34). The previous in-vivo and in-vitro studies confirmed the capacity of TCA and its metabolite, sodium benzoate, on reducing cell death, inflammation and oxidative stress (14, 35-38). However, several researchers have pointed out TCA can induce apoptosis in cancer cell lines at concentrations greater than 30µM (22, 39 and 40). In our study, TCA showed a protective effect against METH at a concentration of 25 µM. TCA significantly decreased the cell viability at higher concentrations and its effect was not in a dose-dependent manner. It may be due to differences in the used concentration of TCA and kind of cell lines.

Effect of TCA on the METH-induced reductions in PC12 cell viability. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. PC12 cells were treated with TCA (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25 and 50 µM) for 24 h in the presence or absence of METH (2.5 mM). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of six separate experiments. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 vs. METH treated group

(A) Flow cytometry histograms of apoptosis assays by the PI method in PC12 cells Cells were treated with TCA (12.5 and 25 µM) for 24 h in the presence or absence of METH (2.5 mM). (B) The bar chart illustrates data as mean ± SEM of six separate experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. control group, ###P< 0.001 vs. METH treated group

Effect of TCA on METH-induced ROS generation. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. PC12 cells were treated with TCA (12.5 and 25 µM) for 24 h in the presence or absence of METH (2.5 mM). Reactive oxygen species were measured using DCF-DA by flow cytometric analysis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of six separate experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. Control, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 vs. METH treated groups

Effect of TCA on METH-decreased GSH generation. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. PC12 cells were treated with TCA (12.5 and 25 µM) for 24 h in the presence or absence of METH (2.5 mM). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of six separate experiments. ***P < 0.001 and **P < 0.01vs. control, ###P < 0.001 vs. METH treated cells

Conclusion

The findings of the present study suggested that TCA exerted a protective effect against METH-induced neurotoxicity through mechanisms related to anti-oxidation and anti-apoptosis. It is suggested that TCA may be useful for the prevention and treatment of harmful effects of METH on the brain.