Introduction

Reducing post-operative pain is an important issue in perioperative patient care.The release of proteolytic and inflammatory mediators after surgical manipulation may cause powerful nociceptive impulses that trigger pain (1). The primary phenomenon in inflammatory pain conduction is the stimulation of the spinal cord’s N-methyl-dimethyl-aspartate (NMDA) receptors to the active forms of glutamate and aspartate amino acids (2). Ketamine, a non-competitive NMDA antagonist, prevents central sensitization of nociceptors at subanesthetic doses with blocking afferent noxious stimulation (3-5) Recently, several studies have shown that the pre-incisional infiltration of the wounds with ketamine could reduce mean pain score after surgery, prolong the time before the first analgesic administration and reduce the total amount of analgesics consumed (6). A recent systematic review on perioperative effects of ketamine showed that intravenous administration of ketamine is an effective complementary for postoperative analgesia and that the pain-relieving effects of ketamine are free of the type of intraoperative opioid prescribed, ketamine amount , and timing of ketamine administration (7). However, to our knowledge no study has compared the analgesic effects of surgical site infiltration of bupivacaine-ketamine with that of IV injection of the ketamine alone.

The present prospective, randomized study was therefore designed to estimate the analgesic effects of the low doses of IV ketamine or intra nephrostomy tract infiltration of two different doses of ketamine plus bupivacaine on pain score after tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) surgery.

Experimental

The present prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial was performed at Sina Teaching Hospital between July 2011 and May 2012. After being approved by the Ethical Board Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) website (2013092612695N1), one hundred relatively healthy patients-classified as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-II -- scheduled for elective PCNL operation, were recruited. In our institution, PCNL is performed in patients with kidney stones more than 2 cm in diameter, stones refractory to extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, proximal ureteral stones larger than 1.5 cm in diameter, diverticular stones, and stones producing distal obstruction.

Patients with a known history of severe hypertension, ischemic heart disease, hyperthyroidism, psychiatric disorders, chronic pain syndrome, renal or hepatic insufficiency, seizure or intracranial hypertension, allergy to ketamine, and drug or alcohol abuse were excluded.

After signing an informed consent, all the patients were visited on the day before surgery at our anaesthesia clinic. Two evaluators who were blind to the intra-operative interventions were told to evaluate the patient’s pain level using a 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS) with 0 standing for ‘no pain’ and 10 for ‘the worst possible pain’. Sedation score was also assessed using Ramsay Sedation Scale as following:

1 = Patient is anxious and agitated or restless, or both

2 = Patient is co-operative, oriented, and relaxing

3 = Patient answers to commands only

4 = Patient exhibits brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus

5 = Patient exhibits a sluggish response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus

6 = Patient exhibits no response

No premedication was prescribed for the patients.The patients were randomized into five equal groups using sealed envelopes, which were prepared by an anesthetic nurse unaware of the objectives of the study. She also prepared and labeled similar syringes containing either normal saline or the study medications as following:

1) 10 mL of saline solution was infiltrated into the nephrostomy tract (group C).

2) 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was infiltrated into the nephrostomy tract (group B).

3) 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine plus 0.5 mg/kg ketamine was infiltrated into the nephrostomy tract (group BK1).

4) 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine plus 1.5 mg/kg ketamine was infiltrated into the nephrostomy tract (group BK2).

5) 10 mL of saline solution containing 0.5 mg/kg ketamine was administered intravenously (group K).

Induction of anesthesia was performed with 0.1 mg/kg midazolam, 3 µg/kg fentanyl, 4 mg/kg of thiopental sodium. We used 0.5 mg/kg of atracurium to facilitate tracheal intubation. Anesthesia was maintained with 1-1.5% isoflurane in a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and oxygen. Fentanyl 1 µg/kg/hr was administered intravenously to provide an acceptable intraoperative analgesia.

During the operation, a ureteral catheter was placed cystoscopically and percutaneous access was obtained while the patient was placed in a prone position. All surgeries were carried out by a single surgeon unaware of the objectives of the study.

As for the first four groups, the nephrostomy tract was infiltrated by the surgeon at the end of the surgery. In group K, however, saline solution plus ketamine administered intravenously at the end of surgery by an anesthesiology resident who was not involved in data collection.

After extubation, patients were transferred to the post anaesthesia care unit (PACU), where an anesthesiologist and nurse unaware of the study objectives, observed the patients. As the primary objective, pain scores were measured at the time of arrival in the PACU as well as 10, 20, and 30 min thereafter and also postoperatively at 1, 6, 12, and 24 h using a 10 cm VAS score. Secondary objectives of the study were as following: 1- Sedation score was assessed during the first 30 min after arriving to PACU using Ramsay Sedation Scale simultaneously with pain scores. 2- The time between the analgesics infiltration and the first administration of rescue analgesics, as well as total analgesic requirement in the first 24 h of the post-operative period. 3- Heart rate, systolic and diastolic arterial pressure, mean arterial pressure, pulse oximeter oxygen saturation, were recorded before the surgery, at five- minute intervals throughout the surgery, at the time of arrival in the PACU, 10, 20, and 30 min postoperatively.

Rescue analgesia during the first 24 h after the surgery was given intravenously (4 mg, bolus dose of morphine) to a maximum total dose of 20 mg upon patients’demand for more pain control. The interval between anesthesia induction and the discontinuation of anesthetic drugs was regarded as the ‘anesthesia duration’whereas the interval between the discontinuation of anesthetic drugs and extubation was considered as the ‘Time to tracheal extubation’. The ‘duration of surgery’ was defined as the interval between the first surgical incision and the last surgical suture.The duration of PACU stay was determined based on the modified Aldrete scoring system (8).

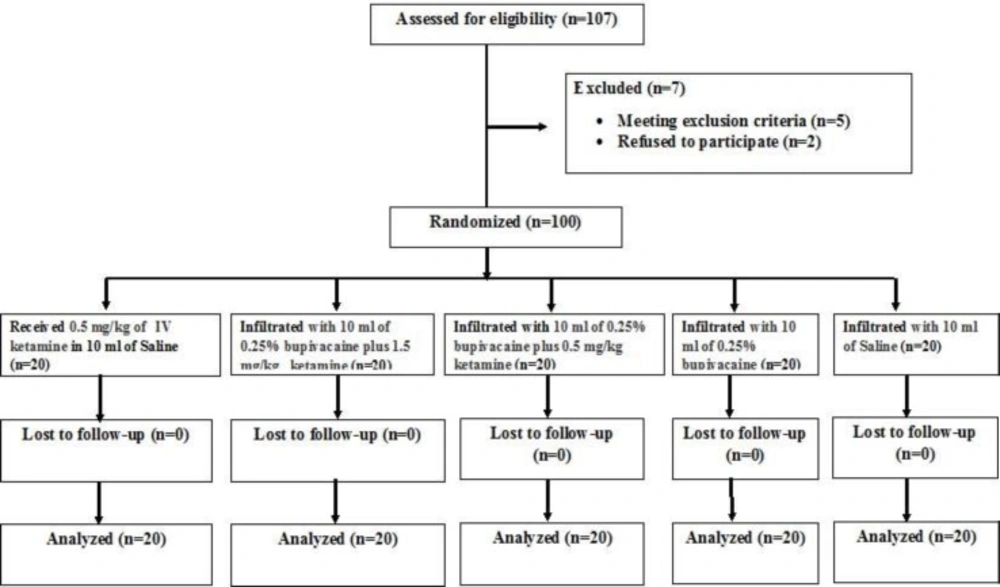

The sample size was calculated based on a power calculation to achieve 80% power to detect a 20% difference in the meanVAS score values between group C and the other groups, with α = 0.05. As a result, 20 patients were required in each group. Baseline data were presented as mean ± standard deviation for quantitative variables and proportions for qualitative ones. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the groups. The flow chart of the study progress is shown in Figure 1.

Results

There was no significant difference between the five groups with regard to their demographic data, duration of surgery, and anesthesia duration (Table 1).

| Variable | Group C | Group B | Group BK1 | Group BK2 | Group K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.2 ± 11.0 | 35.5 ± 8 | 42.5 ± 10.0 | 39.4 ± 12 | 41.5 ± 10 |

| Gender (female/male) | 13/7 | 12/8 | 12/8 | 11/9 | 10/10 |

| Weight (kg) | 65.3 ± 3.2 | 69.4 ± 5.1 | 70 ± 1.5 | 66.7 ± 3.1 | 68.5 ± 2.7 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 95 ± 7.2 | 90 ± 10 | 85 ± 11 | 83 ± 14 | 89 ± 13 |

| Anesthesia duration (min) | 105 ± 8.7 | 104 ± 5.6 | 99 ± 11 | 106 ±9.3 | 102 ±10.4 |

Mean VAS scores were significantly lower in the BK1 and BK2 groups compared with groups C, B and K, whereas mean sedation scores upon arrival at the PACU as well as in 10, 20, and 30 min afterwards was lower in the BK2 group (Table 2). Postoperative mean VAS scores were not significantly different at 1, 6, 12 and 24 h between all groups (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the five groups regarding pulse oximeter oxygen saturation, heart rate, systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure at any point during the surgery and recovery period.

| Variable | Group C | Group B | Group BK2 | Group BK1 | Group K | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS score after arrival in PACU | ||||||

| VAS at 0 (min) | 6.5± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.5* | 1.3±0.5* | 5 ± 0.8 | 0.003 |

| VAS at 10(min) | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.5* | 1.7±0.6* | 5.8±0.7 | 0.004 |

| VAS at 20(min) | 6.2± 0.7 | 4.7±0.6 | 0.7± 0.7* | 2.3 ± 0.7* | 4±0.8 | 0.002 |

| VAS at 30(min) | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 4.2±0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.8* | 2.2 ± 0.8* | 4.4±0.6 | 0.001 |

| Sedation score after arrival in PACU | ||||||

| score at 0 (min) | 1.8± 0.2 | 1.6±0.6 | 5.4±0.4* | 1.3±0.4 | 2.1±1.4 | 0.03 |

| score at 10 (min) | 1.7± 4.8 | 1.4±0.3 | 5 ± 0.5* | 2.1±0.6 | 2.2±0.4 | 0.03 |

| score at 20 (min) | 1.5± 0.5 | 1.3±0.6 | 5.3±0.3* | 2.3±0.9 | 2.7±0.6 | 0.01 |

| score at 30 (min) | 1.0± 1.4 | 1.2±0.7 | 5.2±0.5* | 2.4±0.9 | 2.8±0.4 | 0.02 |

| Postoperative VAS score on ward | ||||||

| VAS at 1 h | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2±0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2.3±0.8 | 0.20 |

| VAS at 6 h | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.0±0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 3.0±0.7 | 0.35 |

| VAS at 12 h | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.8±0.7 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.1±0.2 | 0.10 |

| VAS at 24 h | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 1.2±0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 1.2±0.7 | 0.25 |

, statistical significant difference.

The mean time to first rescue analgesics administration in the postoperative period was significantly longer in groups BK1 and BK2 compared with groups K, B and C (Table 3). The mean of total analgesic requirement in the first 24 h of postoperative period was also significantly lower in groups BK1 and BK2 compared with groups B, K, and C (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the duration of PACU stay between groups. Also, time to tracheal extubation between the five groups was not statistically different (Table 3).

| Variable | Group C | Group B | Group BK1 | Group BK2 | Group K | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to first analgesic demand (min) | 20± 10 | 135 ± 25 | 295 ± 30* | 327±40* | 126 ± 15 | 0.002 |

| Total postoperative morphine requirements (mg) | 16.4 ± 1.7 | 8.5 ± 3 | 4.2 ± 1.5* | 3.5 ± 1.2* | 9.1 ± 2.6 | 0.012 |

| Duration of PACU stay (min) | 28.7 ± 2.2 | 30.4 ± 3.8 | 36.8 ± 3.3 | 37±2.7 | 29.6±2.7 | 0.655 |

| Time to tracheal extubation in operating room (min) | 13.1 ± 1.0 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | 14.7 ± 1.5 | 16.7 ± 1.6 | 13.7 ± 1.3 | 0.275 |

statistical significant difference.

Discussion

The present study shows that multimodal analgesia using ketamine plus bupivacaine lowers mean postoperative pain scores more than the other groups. Results of this study also confirmed that intraoperative nephrostomy tract infiltration of ketamine in combination with bupivacaine not only delays the first demand for analgesic administration but also lessens the total amount of rescue narcotics used for providing analgesia after PCNL surgery.

The local anaesthetic properties of ketamine have been elucidated in many previous studies. Moharari and associates found that administration of ketamine in a mixture with lidocaine gel, compared with lidocaine gel alone, makes rigid cystoscopy more bearable. They concluded that ketamine, due to its peripheral and central nervous system effects, can aleviate pain and therefore result in lower mean VAS score (9). Some researchers found local infiltration of a combination of bupivacaine (10 mg fixed dose) plus ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) into the surgical wound is more effective compared with the infiltration of each drug alone in pediatric adenotonsillectomy operation (10). Also, it was shown by Hosseini Jahromi et al. local spray of ketamine on the surgical site could reduce postoperative pain in children who underwent tonsillectomy (11).

Tverskoy et al (12) found that the infiltration of ketamine and bupivacaine into surgery site during inguinal hernia repair, increases bupivacaine's analgesic efficacy and its analgesic effect duration. Moreover, it has been shown that the administration of IV ketamine is associated with adequate regional anaesthesia in a group of volunteers (13). In this study, mean pain score was higher in those who had received either intravenous ketamine or 0.25% bupivacaine infiltration compared to BK1, 2 groups just at the first 30 min after the end of surgery; so it can be concluded that addition of ketamine to bupivacaine infiltrate increases its’ analgesic effects. In the other word, the results of the current study confirm the local analgesic effects of ketamine. Safavi and associates similarly showed the pre-emptive effects of ketamine infiltration. They found that either subcutaneous infiltration of 2 mg/kg ketamine or intravenous injection of 1 mg/kg ketamine nearly 15 min before surgical incision could provide an equal adjunctive analgesia during first 24 h after surgery in patients undergoing cholecystectomy (14). It should be noted that the present study only focused on local analgesic properties of ketamine after imposing of noxious stimulus and not its pre-emptive analgesic effects. On the contrary to Safavi’s study, however, we found that the infiltration of ketamine plus bupivacaine into the nephrostomy tract has a superior effect on postoperative pain control compared with IV injection of low dose ketamine (0.5 mg/kg). It should be added that high sedation level reported in the group BK2 may disfavor this protocol in PCNL surgeries.

According to table 2 the mean VAS score in patients of group BK2 is lower than BK1 and other groups in recovery period but at the same time the patients in groups BK2 was more sedated and unconscious. The usual dosage of analgesic effect of ketamine by intravenous and caudal administration is less than 1 mg/kg and more ketamine dosage just increase sedation and side effects (15).

Carlton et al. demonstrated that the number of glutamate receptors, found in primary afferent axons, increases after the induction of inflammation (16). Furthermore, the release of neurotransmitters such as glutamate and aspartate into the peripheral tissue is augmented after any type of tissue injury or inflammation (17-18). The stimulation of all types of glutamate receptors may induce hyperalgesia and allodynia which are understood as pain (19-20). Hence, given the above-mentioned facts, the possible mechanism through which the ketamine exerts its local analgesic properties could be understood as the following: The binding of ketamine with NMDA receptors may lower the glutamate-induced stimulation of NMDA receptor on afferent pathways which are located in the nephrostomy tract. Consequently, decreased peripheral pain impulses into the spinal cord ensue and eventually the central sensitization of the pain pathways of the spinal cord may diminish.

It is noteworthy to mention that some researchers evaluated the analgesic efficacy of intra-operative infiltration of local anaesthetics alone on post-operative pain levels in PCNL patients. Shah and associates conducted a study and found that infiltration of bupivacaine as a single local anaesthetic in nephrostomy tract,is associated with requests for less amounts of analgesics during postoperative period in PCNL surgery (21). Goktenand colleagues infiltrated levobupivacaine into the nephrostomy tract and at the same time infused intravenous paracetamol to the patients who were under PCNL operation; They reported their method as a safe and valuable analgesic technique for the PCNL surgery (22). The results of the current study show that the mean amount of rescue analgesics injected to the patients in group B was about half as much as that in group C, supporting the analgesic efficacy of bupivacaine infiltration in reducing pain following PCNL surgery. However, the analgesic efficacy of combined ketamin and bupivacaine, based on our results, was superior to that of a local anesthetic alone.

The current study is subject to two limitations. Considering logistic reasons, we failed to assess the relation between serum levels of ketamine and the resulted post-operative analgesic effects. Thus, further studies are needed to assess serum concentrations of ketamine and determine serum level-response relationships. Moreover, we had to administer rescue analgesia in sufficient amount for all the patients upon their request during post-operative period. Thus, mean VAS scores evaluated at 1, 6, 12, and 24 h after the surgery were not significantly different between studied groups.

Conclusion

It could be concluded that the infiltration of ketamine in combination with bupivacaine, compared with bupivacaine or IV ketamine alone, has better analgesic effects during the recovery period following PCNL surgery.