1. Background

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive bacterium that can cause a wide range of clinical syndromes, from minor infections, such as skin and soft tissue infections, to major infections, such as bloodstream infections (BSIs) and pneumonia. This bacterium usually causes both community-acquired and hospital-acquired infections (1). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections have risen recently and are one of the most severe threats to developed and developing countries. Infections caused by MRSA have been associated with a more severe prognosis than those by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strains (1, 2).

The ability of S. aureus to cause multiple infections is due to the presence of virulence factors and their high expression, some of which are toxin Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, alpha-hemolysin (Hla), and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1). Panton-Valentine leukocidin is a cytolysin toxin encoded by the PVL gene, which causes cations to enter and destroy neutrophils through the pores it creates in them. Leukocidin can act as a virulence agent by destroying leukocytes and eventually reducing their populations in the host body. Toxic shock syndrome toxin belongs to a group of toxins known as pyrogenic toxin superantigens (PTSAgs). Superantigens stimulate T cells by activating the VB variable region on a T cell receptor (TCR) and MHC class 2. Activated T cells release cytokines such as interleukin-1 and TNF-α, which cause shock and tissue damage (3, 4).

Some S. aureus strains, including MRSA, have become a therapeutic challenge due to the increased microbial resistance, especially in hospital-acquired infections (5, 6). On the other hand, there is evidence of increasing community-acquired S. aureus. We are also witnessing the transfer of MRSA from the community to the hospital environment, which raises a matter for consideration (7). Incorrect choice of drugs or inadequate dosing can lead to the development of resistant strains (8).

Because of the increasing use of antibiotics and the upward trend of resistant nosocomial infections, we need to identify pathogens and determine the local patterns of antibiotic resistance as the priorities of the health system in any region. The benefits of antibiotic stewardship programs implemented based on regional patterns include better patient outcomes, reduced drug side effects, including Clostridium difficile infection, resource conservation, and improved antibiotic susceptibility rates (9).

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to investigate the prevalence of MRSA isolated from ICU and non-ICU wards, determine toxic shock syndrome toxin-1, alpha-toxin, and PVL genes in S. aureus strains, and evaluate antibiotic resistance patterns as a clinical guide for clinicians in Southwest Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Patient Samples

This study was conducted from 2018 to 2020. All positive samples were from inpatients and outpatients in Ganjavian hospital, a referral center in the north of Khuzestan province, Southwest Iran. The clinical specimens included blood, skin and soft tissue, tracheal aspirates, and urine, among others.

3.2. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus

Standard microbiological procedures (such as Gram staining, catalase, coagulase, and mannitol fermentation on mannitol salt agar (Merck, USA)) were conducted to detect S. aureus. The PCR test was used to amplify part of the fem gene to confirm that the isolates were S. aureus (10).

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AST) of all isolates was carried out with the disk diffusion (DD) and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) methods as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (11).

The antibiotic discs (BD, USA), penicillin (10 U), gentamicin (10 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), rifampicin (5 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), quinupristin/dalfopristin (15 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), cefoxitin (30 μg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), and linezolid (30 µg) were used for the DD method. Vancomycin, daptomycin, and teicoplanin antibiotics were used for the MIC method. The AST results were interpreted according to the CLSI guidelines M100 (11). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 was used as the control strain. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus was detected using the DD method with cefoxitin disks (30 µg) (BD, USA) (11).

3.4. DNA Isolation

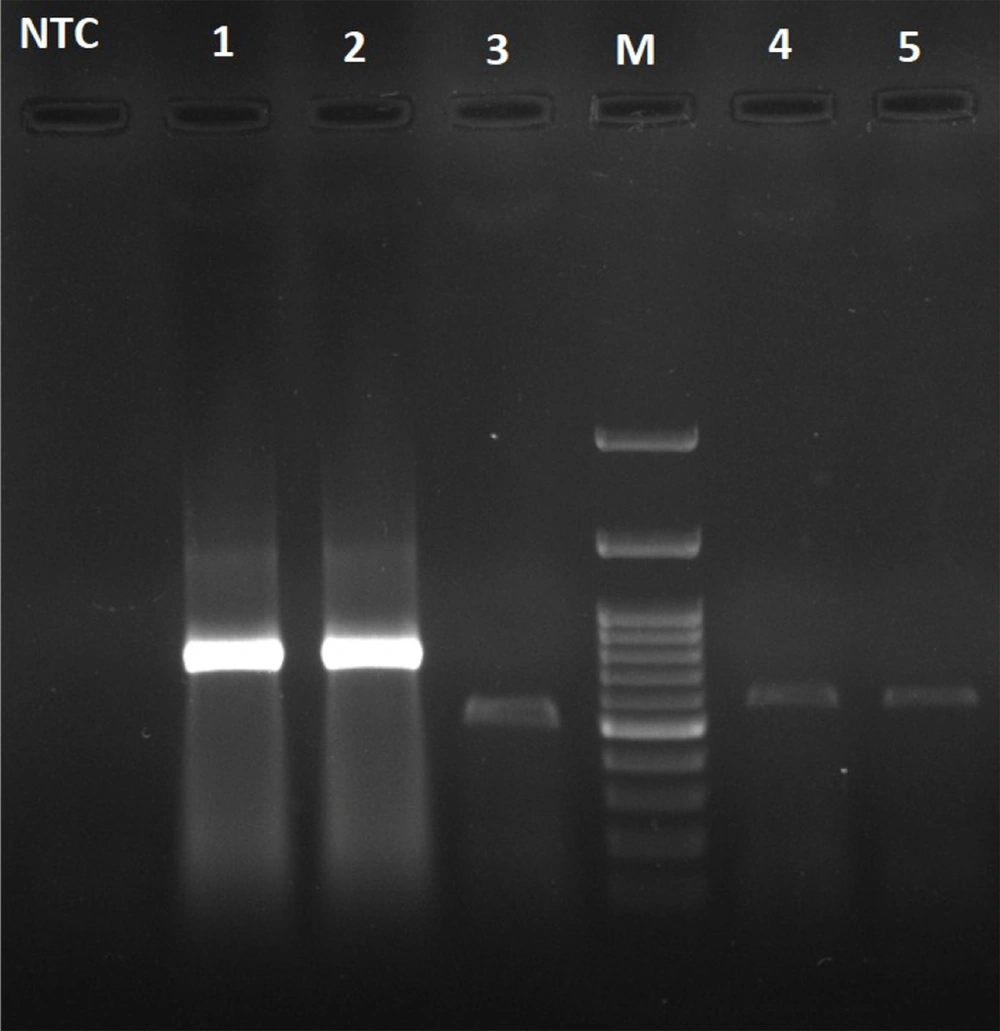

The DNA was isolated from bacterial cells by using the boiling method. The primers specific to the fem, mecA, Hla, PVL, and TSST-1 genes synthesized by Metabion (Germany) are listed in Table 1.

| Sequence Name | Sequence (5' → 3') | Amplicon Length, bp | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| femA F | CTTACTTACTGCTGTACCTG | 685 | (10) |

| femA R | ATCTCGCTTGTTGTGTGC | ||

| mecA F | AGAAGATGGTATGTGGAAGTTAG | 584 | (12) |

| mecA R | ATGTATGTGCGATTGTATTGC | ||

| pvl F | GGAAACATTTATTCTGGCTATAC | 502 | (13) |

| pvl R | CTGGATTGAAGTTACCTCTGG | ||

| hla F | CGGTACTACAGATATTGGAAGC | 744 | (13) |

| hla R | TGGTAATCATCACGAACTCG | ||

| tst1 F | TTATCGTAAGCCCTTTGTTG | 398 | (13) |

| tst1 R | TAAAGGTAGTTCTATTGGAGTAGG |

3.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for each gene was performed in a 25 µL volume containing 1 μL of primer F (10 pmol/μL), 1 μL of primer R (10 pmol/μL), 2.5 μL of DNA template, 12.5 μL of 1× Taq DNA polymerase Amplicon Red Dye Master mix (3 mM MgCl2, 0.2% Tween 20, 0.4 mM dNTPs, and 0.2 units/μL Taq DNA polymerase).

The amplification of fragments specific to all genes was carried out under the following conditions: Initial denaturation (94°C, 5 min), followed by 33 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 s), primer annealing (55°C, 30 s), extension (72°C, 30 s), and final extension (72°C, 5 min). Amplifications were performed with a Bio-Rad T100 thermal cycler (USA). The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with a safe stain. Molecular size markers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were also run to verify the product size. The PCR amplicons were visualized using UV light.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were imported into WHONET 2020 and IBM SPSS V.21 software for statistical analysis and interpretation of AST results. To describe the data, frequency and percentage in qualitative variables were used. Also, Chi-square test was used to analyze the data, and P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

A total of 186 S. aureus isolates were analyzed. Of them, 60.2% (112/186) were isolated from male patients. Among all isolates, 38.2% (71/186) and 54.8% (102/186) were collected from the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and non-ICU wards (general wards), respectively. The remaining 7% of the samples belonged to outpatients.

The majority of the analyzed isolates were from blood (35%), skin and soft tissue (27%), and tracheal aspirate (20%). Of the 186 S. aureus isolates from various specimens, 51 (27.4%) were MRSA. Of the 51 MRSA isolates, 32 and 19 were in the non-ICU wards (general wards) and the ICU ward, respectively (Table 2). The PCR product specific to the fem gene was detected in all isolates. Besides, the mecA gene was detected in all MRSA isolates. In addition, the genetic evaluation results for toxins (PVL, Hla, and TSST-1) are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1.

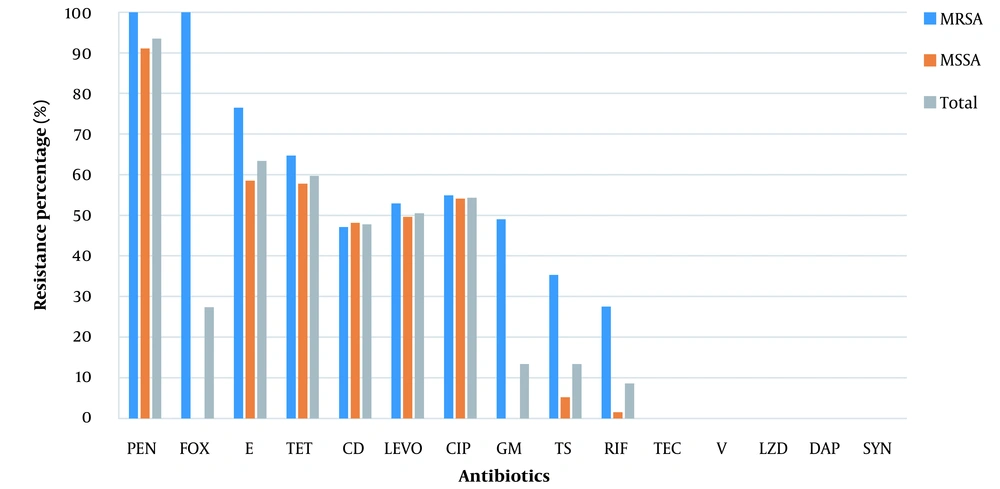

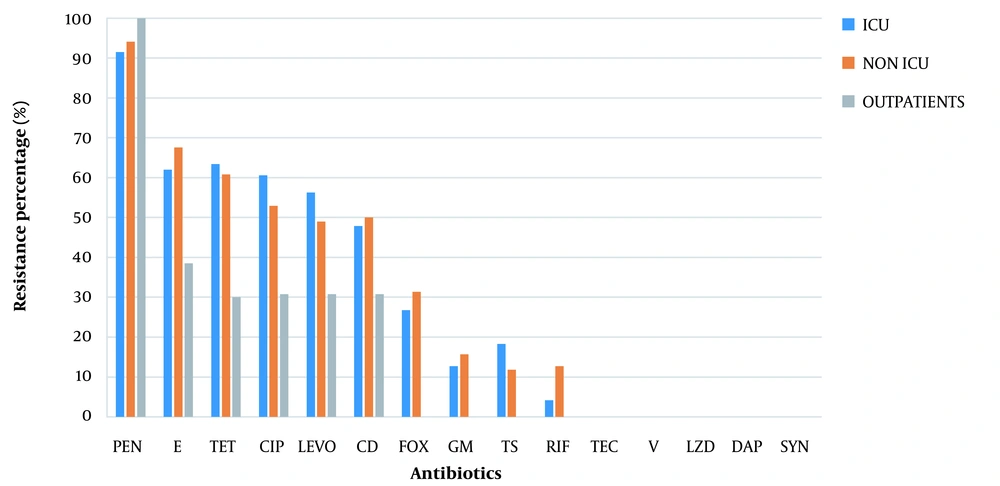

The AST results of MRSA, MSSA, and S. aureus isolates are shown in Figure 2, and the antimicrobial resistance profiles of S. aureus isolates in the non-ICU patients, ICU patients, and outpatients are presented in Figure 3.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of MRSA, MSSA, and Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Penicillin (PEN), cefoxitin (FOX), erythromycin (E), tetracycline (TET), clindamycin (CD), levofloxacin (LEVO), ciprofloxacin (CIP), gentamycin (GM), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TS), rifampin (RIF), teicoplanin (TEC), vancomycin (V), linezolid (LZD), daptomycin (DAP), quinupristin-dalfopristin (SYN).

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in non-ICU wards, ICU patients, and outpatients. Penicillin (PEN), erythromycin (E), tetracycline (TET), ciprofloxacin (CIP), levofloxacin (LEVO), clindamycin (CD), cefoxitin (FOX), gentamycin (GM), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TS), rifampin (RIF), teicoplanin (TEC), vancomycin (V), linezolid (LZD), daptomycin (DAP), quinupristin-dalfopristin (SYN).

| Sample | MRSA | MSSA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical specimens | |||

| Blood | 18 (28.1) | 46 (71.9) | 64 (100) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 13 (26) | 37 (74) | 50 (100) |

| Tracheal aspirate | 10 (27) | 27 (73) | 37 (100) |

| Urine | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | 19 (100) |

| Others | 4 (25) | 12 (75) | 16 (100) |

| Different wards | |||

| Non-ICU wards | 32 (31.4) | 70 (68.6) | 102(100) |

| ICU | 19 (26.8) | 52 (73.2) | 71(100) |

| Outpatients | 0 | 13 (100) | 13 (100) |

| Total | 51 (27.4) | 135 (72.6) | 186 (100) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%)

| Gene | Hla | TSST-1 | PVL |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA and MSSA strains | |||

| MRSA | 39.2 | 3.9 | 2 |

| MSSA | 41.5 | 4.4 | 0 |

| P-value | 0.779 | 0.875 | 0.103 |

| Different wards | |||

| Non-ICU wards | 40.8 | 7 | 1.4 |

| ICU | 44.1 | 2.9 | 0 |

| Outpatients | 15.4 | 0 | 0 |

| P-value | 0.139 | 0.311 | 0.443 |

| Clinical specimens | |||

| Blood | 45.3 | 4.7 | 0 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 46 | 4 | 2 |

| Tracheal aspirate | 32.4 | 8.1 | 0 |

| Urine | 36.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| P-value | 0.723 | 0.541 | 0.744 |

| Total | 40.9 | 4.3 | 0.5 |

a Values are expressed as %.

5. Discussion

In this study, the incidence of MRSA infection was observed (27.4%) in all samples. Of 51 patients with MRSA infection, 62% and 37% were admitted to general wards and the ICU, respectively. Various studies have shown that the prevalence of MRSA varies depending on the geographic region. For instance, MRSA has been reported to be more prevalent in Southern Europe than in Northern Europe, and a prevalence of 2.3% to 69.1% has been reported for some regions in Asia (14). Also, the prevalence of hospital-acquired infections caused by MRSA is still above 50% in many countries (4).

One of the main goals of this study was to determine the incidence of MRSA in the ICU because the latest studies recommend that empiric therapy against MRSA be started for patients when more than about 10 - 20% of S. aureus isolates are methicillin-resistant, especially for some severe infections such as bacteremia or hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). In the present study, the incidence of MRSA in the ICU was 26.8%, and since no similar study has been conducted in our referral treatment center, it is recommended to start antibiotic treatment against MRSA until the culture and AST results are available (15). Therefore, if it is necessary to start treatment for these severe infections, quinupristin-dalfopristin, daptomycin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, or linezolid can be prescribed depending on the infection site. Indeed, it should be noted that daptomycin is not a good option for treating MRSA pneumonia due to the weak penetration of the drug into the lung tissue (16).

Fluoroquinolones have always been considered effective in treating infections caused by S. aureus. However, because of the high and irrational use of this class of drugs, the microbial resistance to quinolones is increasing worldwide (17, 18). In a study conducted by Yitayeh et al. from 2015 to 2018, 137 positive cultures were evaluated for antibiotic resistance by the disk diffusion technique. Also, 10.4% of Gram-positive strains were S. aureus. Besides, 60% of S. aureus species were MDR, and about 49% of Gram-positive species were resistant to ciprofloxacin (19). In our study, quinolone exhibited relatively high resistance (more than 50%) to all isolates of S. aureus and MRSA. Therefore, to treat infections caused by S. aureus, especially MRSA, in this geographical area, the choice of fluoroquinolones without access to antibiotic susceptibility testing is not logical.

This study implied that penicillins are not a good option for treating staphylococcal infections because of the high resistance of S. aureus to this class of drugs (more than 93%). Similarly, in a 2020 review article by Tsouklidis et al., penicillin treatment for staphylococcal infections was not successful (20).

In two studies conducted in Iran, MRSA species showed high resistance to aminoglycosides, especially gentamicin. In a study by Rahimi and Torabi in Isfahan, Iran, in 2017, the rate of MRSA resistance to gentamicin was over 60% (21, 22). In a review study by Darvishi et al., the resistance of Staphylococcus species to gentamicin was about 80% (23). On the other hand, in our study, 13.5% of all S. aureus isolates and about half MRSA isolates were resistant to gentamicin. In addition, the resistance rate of both S. aureus and MRSA species to clindamycin was about 48%. Based on similar studies conducted in our country, the resistance rate of MRSA to aminoglycosides is high, so it seems that this class of drugs is not a good option for treating MRSA infections.

Hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA) causes serious infections such as bacteremia and pneumonia and is often resistant to at least one of the drugs used for this organism. In our study, most infections caused by MRSA were of nosocomial origin and isolated from blood, skin and soft tissue, and respiratory secretions. According to similar studies, HA-MRSA infections are usually related to the patient's underlying disease, exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, or hospital procedure complications. Therefore, controlling the underlying disease, continuously monitoring antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and adhering to nosocomial infection control measures are particularly important to preventing MRSA nosocomial infections (24, 25). We usually expect more MRSA infections in the ICU than in non-ICU wards (26, 27). However, our study did not show this pattern, and even the prevalence was slightly higher in non-ICU wards (31.4% in non-ICU vs. 26.8% in ICU). Also, due to the risk of transmitting the resistance pattern to acquired organisms from the community, we should consider the risk of more severe community-acquired MRSA infections in the future.

Rossato et al. in Brazil and Kot et al. in Poland showed no resistance to vancomycin, linezolid, or teicoplanin (28, 29). Also, in a study by Kayili and Sanlibaba in Turkey, no resistance to linezolid was reported in any of the S. aureus strains, but low resistance (18.8%) was observed to vancomycin (30). Fortunately, in our study, all strains of S. aureus were sensitive to vancomycin, linezolid, and teicoplanin. However, it should be noted that MRSA species can acquire antimicrobial resistance factors very quickly, so we think we cannot rely only on this study's results. Therefore, the antimicrobial resistance pattern of S. aureus strains should be examined continuously.

Staphylococcus aureus strains capable of producing PVL are more likely to cause severe infections such as necrotizing pneumonia and skin and soft tissue infections. In a study by Kwapisz et al. on MRSA and MSSA strains, the detection of the PVL gene was much more common in MRSA than in MSSA isolates (31). In another study by Zerehsaz et al. on 215 hospital strains of S. aureus in Tehran, Iran, the PVL and TSST-1 genes were found in 1.4% and 32.3% of the isolates, respectively (32). In this study, the prevalence of the PVL gene was significantly higher in MRSA strains (2%), while in all Staphylococcus strains, it was about 0.5%. On the other hand, the prevalence of the TSST-1 gene in all S. aureus strains was 4.3%. Regarding the detection of the PVL gene, the results are almost similar to previous studies, except that in our study, the prevalence of the TSST-1 gene was much lower. Although the prevalence of the PVL gene was relatively low, its higher detection in soft tissue infections is noteworthy. It seems that skin and soft tissue infections caused by S. aureus, especially MRSA, in this center should be seriously taken because there is a possibility of rapid progression to severe disease.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, in case of severe infections in the ICU such as bacteremia and HAP/VAP, it is recommended to start empiric treatment against MRSA with either quinupristin-dalfopristin, daptomycin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, or linezolid until the culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing results are available. Nevertheless, to start treatment for other infections caused by S. aureus strains, the choice of medication should be made based on the antibiotic resistance pattern.