1. Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the second known cancer in the world (1) and the second cause of death related to cancer in Iran (2). In Iran, BC is the second cause of death due to cancer, with a prevalence of 29.88 per 100,000 women per year, and Tehran, Isfahan, Mazandaran, Markazi, and Tabriz provinces have the highest rates in the country (3).

Development of BC and its treatment causes loss of breasts after mastectomy (3), alopecia after chemotherapy (4), decreased libido, and pain during intercourse after hormone therapy and chemotherapy (5). Other changes in the appearance of hand edema patients include darkening of the skin and nails (6), which along with the lack of breasts, decreases the patient’s sexual attractiveness (7). Mood changes in anger, anxiety, and depression are observed in patients (8). These changes cause husbands of women undergoing mastectomy to change their views on the patient (9). Husbands are known as the first caregivers of women with BC (10), and studies have shown that the husbands of these patients experience much stress, which affects their quality of life (11). They also experience physical disorders, lack of support, changes in roles, and fear of the future (12), which can effectively change their attitude toward the patient. On the other hand, the attitude toward the patient determines the type of communication and behavior with the patient (13).

Although most husbands respond well to seeing their wives undergo a mastectomy, a small group of husbands report it is a challenging experience. Thus, emotional support, information, attitude, and religion are the factors that help them to cope with the disease (14), indicating the important role of attitude and religion in dealing with a problem (15).

Even though many studies have mentioned the role of husbands’ attitudes toward their women with BC regarding the type of care provided by them, no research was found on the attitude toward the patient by Iranian husbands. Therefore, identifying the views of Muslim Iranian husbands of women with BC after being diagnosed with the disease is important to identify the problems between couples in the post-disease period.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

In this conventional content analysis study, 18 participants were selected using targeted and convenience sampling, which included 4 therapists, 5 patients, and 9 patients’ husbands in Ahvaz Shahid Baghai Hospital from Jan to May 2022.

2.2. Sample and Recruitment

Inclusion criteria were familiarity with the Persian language, appropriate physical and mental status, and passage of six months from cancer diagnosis, mastectomy, and chemotherapy. The therapist’s inclusion criteria included having at least a bachelor’s degree and 2 years of experience working with BC patients. Sampling was continued until data saturation was reached. The number of interviews was determined using the principle of data saturation.

2.3. Data Collection

First, the patients were explained the study objectives and procedures and ascertained that they would be provided with treatment if they lacked cooperation. In addition, they were assured about the confidentiality of their information, and they were not required to pay any costs and would be provided with the study results. Then, their online informed consent forms were obtained, and the interviews were performed. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted through phone calls at a convenient time for the participants. After introducing the interviewer and expressing the objectives, the patients’ husbands were asked semi-structured questions.

It should be noted that the interviews were recorded after gaining the participants’ consent. The interviews were begun with questions such as “What is your view on cancer”? They continued with more specific questions based on the primary interviews and the main themes.

2.4. Data Analysis

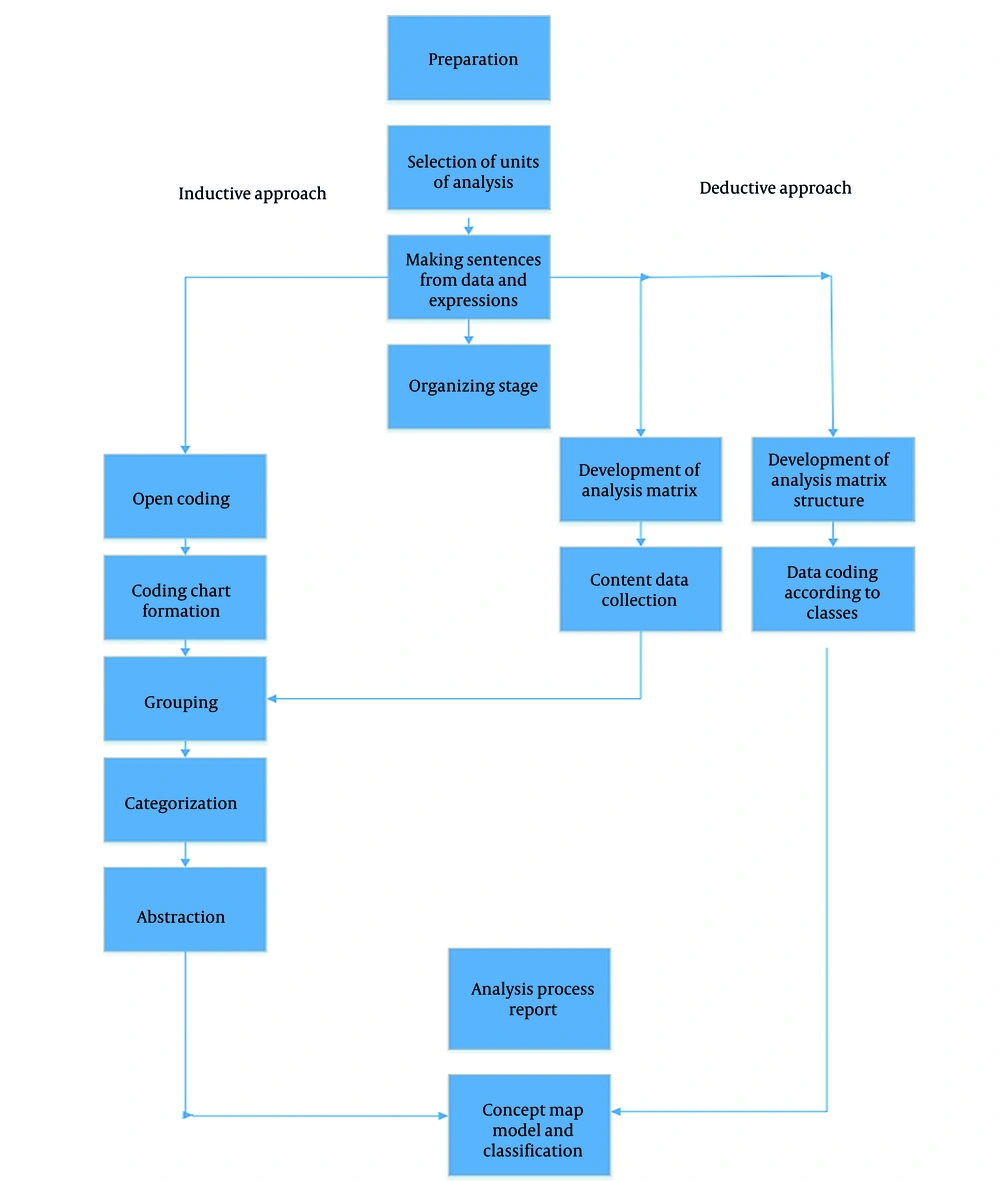

Content analysis was used to analyze the data based on the method by Elo and Kyngas (16). Following the interviews, the records were transcribed into text, and the notes were read several times to approve the transcription. Repeated data induction, comparison, reasoning, and deduction, we summed, codded, and classified repeated relevant sentences, words, and paragraphs, followed by analysis, and relevant themes were extracted (Figure 1).

2.5. Trustworthiness

The trustworthiness of this study was established using Lincoln and Guba’s (17) criteria, including credibility, dependability, transferability, and conformability. The credibility was confirmed by prolonged engagement. This researcher was engaged in studying end-of-life patients for eight years. Also, she was a nurse and instructor in the oncology ward leading to appropriate relationships with the participants. The researcher and the subjects have been colleagues in the past and have provided the basis of trust and the right atmosphere for in-depth interviews. Member checking was performed so that some parts of the texts, along with the relevant categories and codes, were sent to some supervisors to achieve their ideas regarding the data analysis process. To ensure appropriateness, some nurses not involved in the study were provided with the results and asked to approve the appropriateness of the findings. Also, sampling with maximum variation was applied to ensure the results’ transferability. To determine conformability, we recorded and reported the study processes accurately, which provided the ground for further follow-up.

3. Results

The present study had 18 participants, including 9 husbands, 5 patients, and 4 therapists. The education level of the participants was as follows: 3 Ph.D., 1 master’s degree, 3 bachelor’s degrees, 4 associate degrees, 4 diplomas, and 3 high school degrees (Table 1). The extracted themes are as follows (Table 2).

| Code | Age | Education | Job | Duration of Marriage (Y) | Number of Children | Duration of Breast Cancer (Y) | Type of Mastectomy | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | Associate degree | Retired | 30 | 2 | 7 | Partial | Patient |

| 2 | 49 | High school | worker | 27 | 2 | 2 | Unilateral mastectomy | Patient |

| 3 | 51 | Associate degree | Employee | 25 | 3 | 2 | Unilateral mastectomy | Husband |

| 4 | PhD | Employee | Therapist | |||||

| 5 | PhD | Employee | Therapist | |||||

| 6 | 40 | Associate degree | Self-employed | 14 | 2 | 6 | Unilateral mastectomy | Husband |

| 7 | 36 | Diploma | worker | 9 | 1 | 3 | Bilateral mastectomy | Patient |

| 8 | Bachelor’s degree | Employee | Therapist | |||||

| 9 | 50 | Masters’ degree | Employee | 30 | 2 | 13 | Partial | Husband |

| 10 | 49 | Diploma | Employee | 24 | 2 | 5 | Bilateral mastectomy | Patient |

| 11 | 49 | High school | worker | 27 | 2 | 2 | Unilateral mastectomy | Husband |

| 12 | 65 | High school | Retired | 33 | 1 | 13 | Unilateral mastectomy | Husband |

| 13 | 61 | Diploma | worker | 40 | 1 | 4 | Partial | Husband |

| 14 | 60 | Diploma | Self-employed | 28 | 2 | 7 | Unilateral mastectomy | Husband |

| 15 | 36 | Bachelor’s degree | Employee | 2 | 0 | 1 | Unilateral mastectomy | Patient |

| 16 | 40 | High school | Employee | 20 | 2 | 3 | Unilateral mastectomy | Husband |

| 17 | PhD | Employee | Therapist | |||||

| 18 | 54 | Associate degree | Employee | 33 | 2 | 11 | Partial | Husband |

Demographic Characteristics of the Husbands of Iranian Women with Mastectomy

| Theme | Main Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| From the queen to gorgon | Positive attitude toward the patient | Making the patient more beautiful after illness |

| The stability of the patient’s beauty before and after the disease | ||

| Knowing the patient as a hero | ||

| Negative attitude toward the patient | Loss of beauty after disease | |

| Decreased patient’s attractiveness after disease | ||

| Disfigurement after disease treatment | ||

| Acceleration of the aging process in the last days of life |

Attitudes Toward Patients in Muslim Husbands of Iranian Women with Mastectomy: From the Queen to Gorgon

3.1. Positive Attitude Toward the Patient

3.1.1. Making the Patient More Beautiful After the Disease

Some participants stated that after their patient was diagnosed with cancer and during treatment, their interest in their patient increased.

“Whenever I think of my wife, the image of an angel comes to my mind because she was really kind and did not hurt anyone during her illness.” (P. 6)

3.1.2. The Stability of the Patient’s Beauty Before and After the Disease

In the present study, most participants stated that their attitudes did not change before and after the disease and their interest in their patients did not decrease.

“It’s true that my wife lost her hair and breasts, but it didn’t make my love for her decrease because love for a wife is more than love for her body.” (P. 3)

“I was very sad because I had given birth to breasts, but my husband says that you are very beautiful without breasts.” (P. 7)

3.1.3. Knowing the Patient as a Hero

Some participants stated that disease is like a war, and cancer is the champion of this war and always wins.

“My wife is a hero because she fights her illness every day, and because of her resistance, I love her even more than before.” (P. 18)

3.2. Negative Attitude Toward the Patient

3.2.1. Loss of Beauty After Illness

According to some participants, having thick hair and breasts is considered beautiful, and a woman without these two is not beautiful at all.

“My husband always tells me that you only had beautiful hair and you lost it.” (P.15)

3.2.2. Decreased Patient Attractiveness After Illness

Some participants stated that they do not want to have sex with the patient after mastectomy, and it is not impressive in terms of appearance.

“Indeed, when a woman loses her breasts and hair, her attractiveness decreases.” (P.16)

3.2.3. Disfigurement After Disease Treatment

From the point of view of some participants, after passing the disease and the complications of the disease and treatment in the patient, the patient’s beauty gradually decreases, and at the end of life, it becomes the ugliest possible state.

“My husband always tells me that you are ugly, and you have become even uglier. He always makes fun of me because of my appearance”. (P.15)

3.2.4. Acceleration of the Aging Process in the Last Days of Life

Some of the participants stated that during the treatment of the disease, especially at the end of the disease, old age is evident in the patient’s face and position, which can be due to severe lethargy of the disease and loss of physical strength.

When I took my wife to the hospital in the last few days, other patients thought that she was my mother”. (P.6)

4. Discussion

In the present study, the views of husbands towards the patient were different and varied from the increase of interest between the spouses to the decrease of interest in the patient after the illness, which indicates that the attitude towards the patient and the illness is influenced by social, economic and cultural factors (18). Following mastectomy and other BC treatments and the occurrence of a decrease in sexual attractiveness, husbands have unfulfilled sexual needs, which can affect their view of the patient and the disease and the relationship between them (19). The effect of love on cancer is one of the unsolved problems of patients and their husbands (20). Conversely, for couples who can overcome illness-related relationship challenges, there is potential for mutual growth and deepening and strengthening of the relationship (21), and some believe that it causes their personality growth (22).

Studies have shown that in cases where interest in the patient is reduced after the disease, the violence toward the patient increases until the patient admits that they suffered the most from their husbands, even more than cancer (23). This issue increases the patient’s vulnerability and affects the quality of care the husband provides (24).

On the other hand, Islam has allowed men to remarry whose wives are suffering from incurable diseases and cannot meet their wife’s sexual needs (25). For this reason, incurable diseases are the reason for the couple’s conflicts, in some cases leading to leaving a spouse or remarrying, which in Iranian culture and from the women’s perspective, remarriage is one of the examples of cheating on the spouse (26).

4.1. Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is that it is based on culture, and different results may obtain in other cultures, which is a characteristic of a qualitative study. Another limitation of this study is that most of the participants were married for more than 20 years and more than ten years due to illness; thus, the results of this study may not be generalizable to spouses who have recently been involved in illness or recently married.

4.2. Conclusions

According to the results of the present study, the views of husbands of women undergoing mastectomy are very different, which must be considered in psychological interventions between couples after illness because it can determine the relationship between couples and the quality of care provided to patients by husbands.

4.3. Relevance to Clinical Practice

The results of this study can be used to inform policy when providing holistic care. They also highlight the importance of counseling and support interventions for partners of BC patients.