1. Context

Three decades ago, research has accumulated compelling evidence that diets high in vegetables and fruits may be preventive against the risk of developing many chronic diseases. Some therapeutic herbs derived from plants have recently garnered considerable interest owing to their broad spectrum of pharmacological effects (1, 2). The therapeutic effects of herbs, nutritional supplements, and medicinal plants were evaluated for various diseases and chemo-preventive impact on cancer (3). The decreased risk of diseases and toxic effects related to their consumption at high concentrations implies that defined amounts of bioactive components derived from these sources exert therapeutic benefits without generating any damage (4-6). Natural compounds are thought to decrease the inflammatory processes that lead to neoplasia, hyper-proliferation, stimulation, advancement of the carcinogenic process, and angiogenesis (7). Recent studies show that a wide range of silymarin may help ward off cancer, slow its spread to other parts of the body, or even cure it when used with standard chemotherapy methods (7).

The most abundant sources of silymarin are the seed and fruit of milk thistle, while other plant sections, such as the leaves, may also contain less concentration (8). One of the critical points about silymarin is that it is a safe herbal substance with no known health risks or adverse effects when used in prescribed therapeutic doses. Many plants include physiochemical compounds that may interact with prescription medications, affecting their pharmacokinetics and causing clinically relevant consequences. This article summarizes recent research on the chemistry of silymarin, its pharmacokinetics, and its therapeutic applications (5).

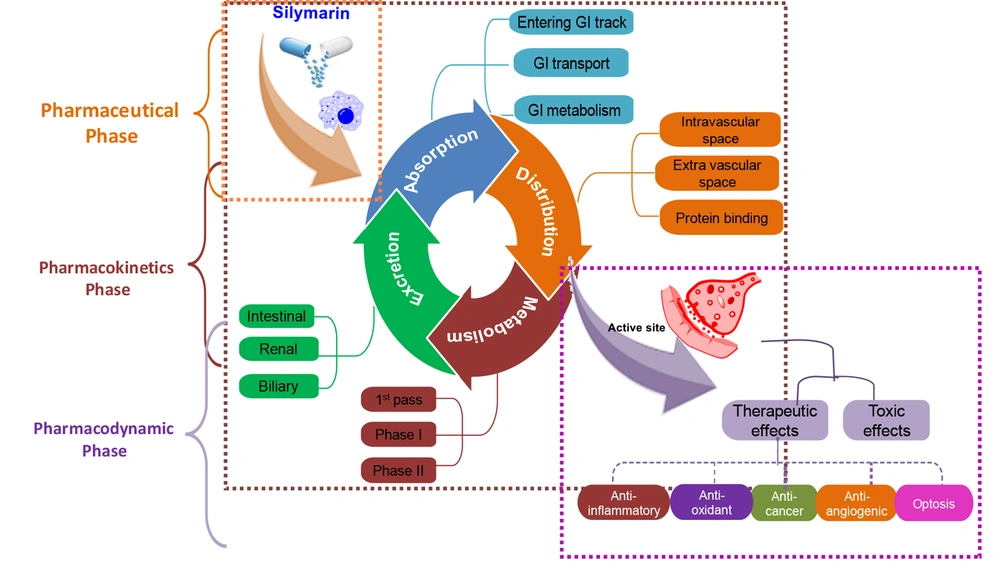

2. Pharmacokinetics of Silymarin

Pharmacokinetics (PK) is a term that refers to the process through which a compound is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted from the body. The PK statistics of a chemical give information on systemic exposure to the kinetic models. Furthermore, PK is important to calculate the therapeutic potential and effectiveness of prescribed dosages of certain medications (9, 10). Silibinin is the predominant molecule and is also considered the active metabolite in most scenarios (11). Silibinin may be taken orally in amounts of up to 1.44 g per day for up to a week and is considered safe by experts (9, 12). The silymarin's components have sparingly solubility in water, and research demonstrated that orally administrated powder extracts result in plasma concentrations of only 20 ng/mL after 30 minutes. The bulk of the silybin found in the bloodstream was in the form of conjugated silybin. Conjugated silybin is the main component found in the bloodstream (13). The total silybin urine recoveries accounted for less than 3% of the total dose administered (14).

However, pharmacokinetic studies have revealed that silybin's bioavailability is improved when combined with phosphatidylcholines, such as in the formulations of Silipide (IdB 1016) and Siliphos (6). It was found that the silibinin-phosphatidylcholine formulation IdB 1016 (silipide) had increased oral availability when compared to silymarin, resulting in higher peak plasma levels in healthy participants (13). In an experiment, the IdB 1016 was administered to clients possessing colorectal cancer (15) at different concentrations (1440, 720, and 360 mg of silibinin) daily for 7 days (5). According to the results, silibinin levels in the blood ranged from 0.3 to 4.0 n-mol/L (5, 16) in the liver from 0.3 to 2.5 nmol/g, and in colon tissue from 20 to 141 nmol/g (5). The route of the silymarin administration following its pharmacokinetics and leading to therapeutic effects is shown in Figure 1.

2.1. Absorption

The collection of evidence from both in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrates that silymarin is absorbed by the intestinal epithelia. Silymarin is insoluble in water and is commonly used as an encapsulated supplement. Silymarin is readily absorbed when administered orally. The maximum plasma concentration is reached after 6 - 8 hours. Silymarin is only absorbed by the body by about 23% to 47% when taken by mouth, which means that it has a low bioavailability. It is typically a reference extract (70 - 80 percent silymarin) that recovers at about 2 - 3% after oral delivery (17, 18). Because of silymarin's limited solubility, the compound's bioavailability has been a key source of concern during clinical studies. The Cmax was around 340 ng/mL after intravenous injection with an oral dose of 560 mg (19) of the compound silymarin (equivalent to 240 mg silibinin) (19, 20). Research conducted on animals revealed that when silibinin (500 mg/kg) was administered via the gastrogavage system, the concentration of total silibinin and unconjugated were 76.15% and 8.52%, respectively. According to the research, silibinin has been shown to have an absolute absorption and bioavailability of around 0.95 percent in rats. This low bioavailability might be attributed to phase II conjugation's high reactivity and low absorption rate (19).

2.2. Distribution

It was revealed that silibinin, whether gratis or conjugated, has fast tissue dispersion. The silibinin concentrations in the tissues were tested, and it was discovered that they reached their highest levels within 1 hour after administering a compound (silibinin) at a dosage of fifty mg/kg to mice (SENCAR) (19). Additionally, the concentrations of free and conjugated silibinin in the connective tissues have also been investigated. The Cmax values for the liver, lungs, stomach, skin, prostate, and pancreas were 8.8/1.6 (mean/SD) and 5.79/1.10 (mean/SD) per gram silibinin, respectively (7, 21). A study found that the protein binding of Silibinin in the blood of rats was 70.3 to 46%. Silibinin is quickly and easily absorbed by the bile, resulting in increasing the concentrations of bile up to 100 times than those found in the blood, and endogenous lipoprotein may transfer it from the liver to the extrahepatic organs. The profile of the conjugates in plasma showed additional peaks (15, 19) after taking a 600 mg oral dose of Silybum marianum extracts to 3 volunteers, indicating enterohepatic recycling (15, 19, 22).

2.3. Metabolism

Silibinin is metabolized in phases I and II, with a strong emphasis on phase II conjugation processes, and it is conjugated several times in individuals. Studies showed that silibinin was metabolically degraded in human liver microcosms. Notably, a prominent demethylated metabolite, along with 3 lesser mono-hydroxyl metabolites and one minor di-hydroxyl metabolite, were detected (19). Six healthy male volunteers were administered Silymarin pills containing varying doses of silibinin, specifically 102 mg, 153 mg, 203 mg, and 254 mg (19). After ingesting the pills, it was observed that merely 10% of the bloodstream's total silibinin concentration was in its unconjugated form (19, 23). The majority of silibinin circulating throughout the body had formed conjugates with sulfates and glucuronides after the administration of silibinin (19). Silibinin metabolism in humans involves several compounds, including silibinin monosulfate, silibinin glucuronide sulfate, silibinin monoglucuronide, silibinin diglucuronide, O-desmethyl silibinin glucuronide, and silibinin triglucuronide (17). The distribution of unbound, glucuronidated, and sulfated silymarin in the plasma of 3 healthy individuals accounted for approximately 17%, 28%, and 55% of the total dose, respectively (19).

2.4. Elimination

In vivo, silymarin, whether gratis or conjugated, is quickly removed. However, silybin's renal excretion is minimal and barely contributes 1% to 2% of an oral dosage over 24 hours. Silybin is excreted mainly via the liver and bile, as shown by the biliary concentrations of silybin in patients that were about 100 times higher than the serum concentration. The active transport theory of silybin was suggested based on the distribution ratio of total silybin of 29 ± 9.5 and the assumption that silybin is discharged into the bile by active transport (24). Alike other flavonoids, silybin's pharmacokinetic attitude is entero-hepatic, with excreted glucuronidated silybin being reabsorbed by bacterial enzymatic breakage of glycosidic linkages, as evidenced by 2 peaks within the curve of plasma’s concentration (19, 25). Researchers have found that bio-enhancers can increase the pharmacological effects and bioavailability of silybin in vivo by targeting transporters responsible for absorption and excretion. Silibinin excretion ranges from 1 to 7 percent of the dosage in the 24 hours following an oral dose of silymarin, which is equivalent to 240 mg of silibinin (19, 26).

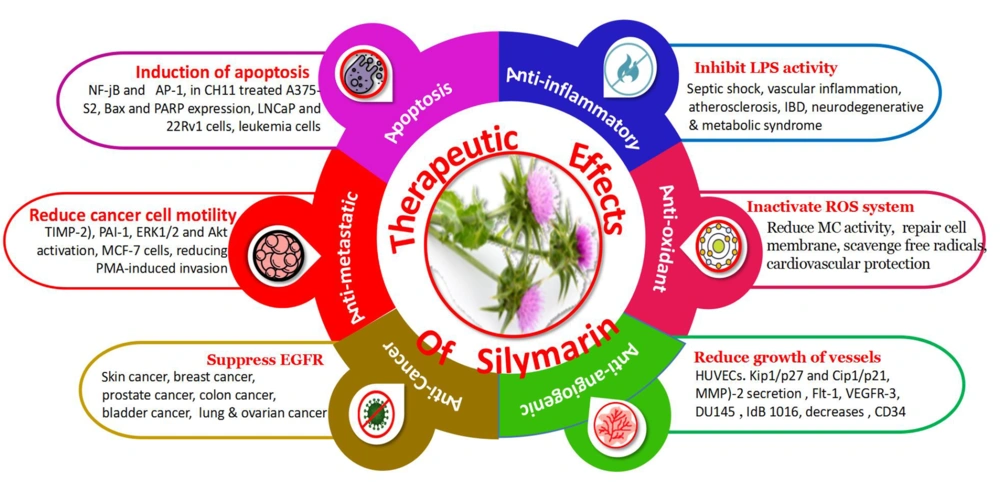

3. Therapeutic Potentials of Silymarin

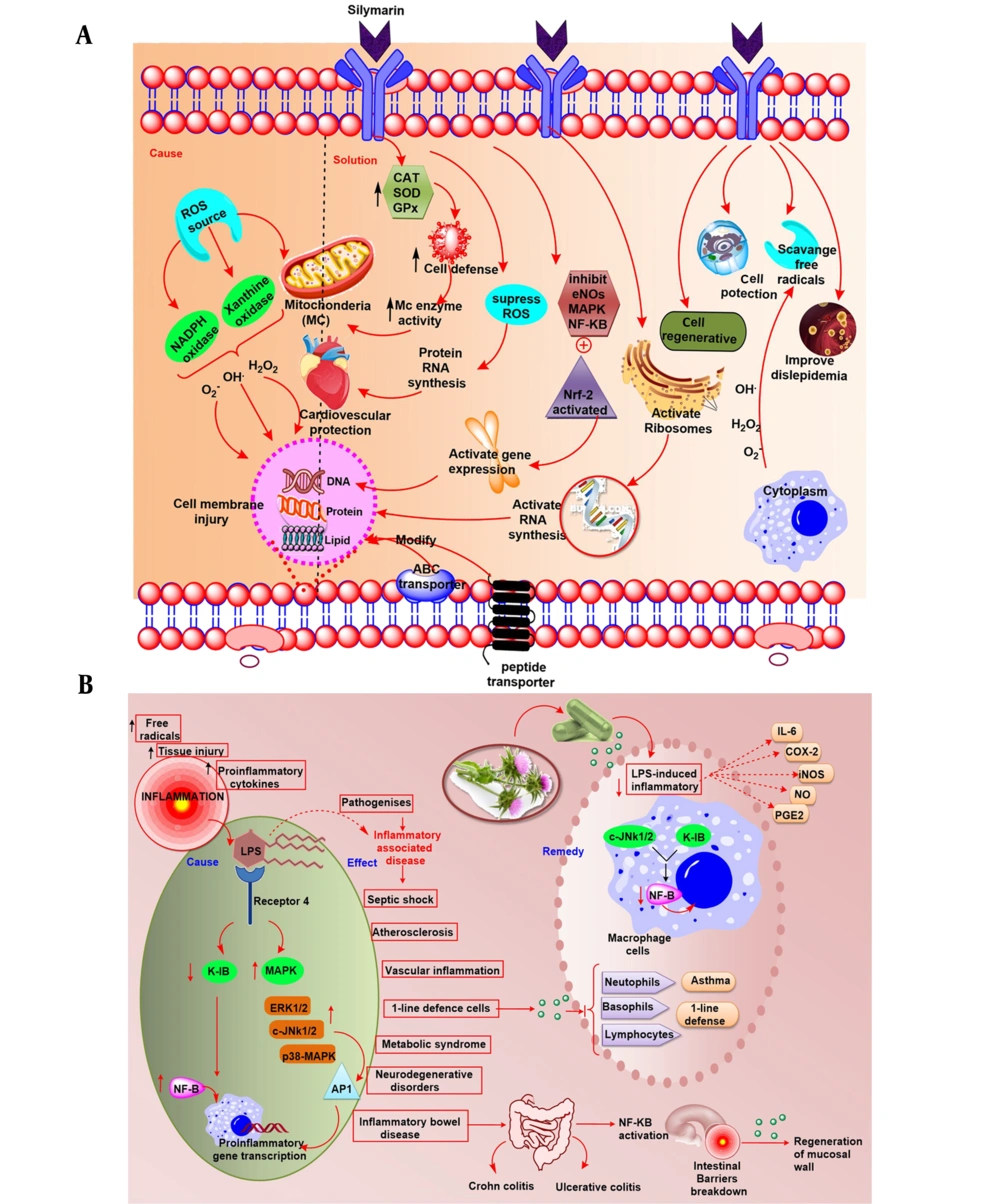

The therapeutic effectiveness of silymarin is mediated by several molecular pathways that are now rarely discussed. Silymarin is well renowned for its liver-protective, antioxidative, anti-fibrotic, and chemoprotective properties (10). Silymarin's hepatoprotective action has been linked to its antioxidant and membrane-stabilizing properties. Silymarin is a potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, anti-angiogenic, and apoptosis (19, 27). The therapeutic potential of silymarin is given in Figure 2.

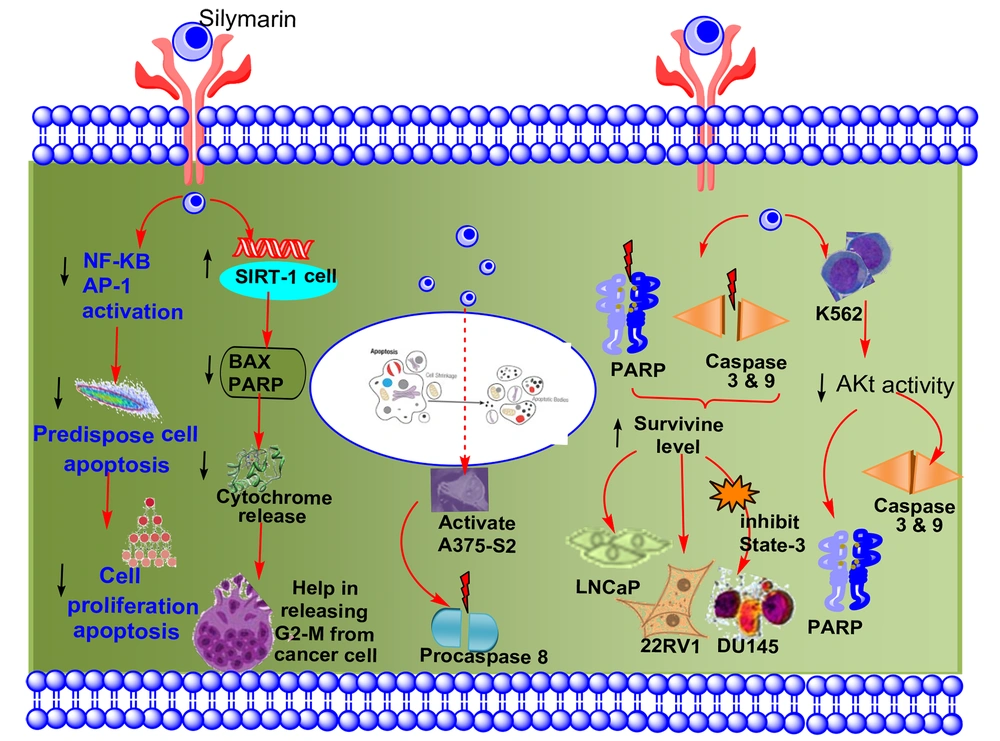

3.1. Anti-cancer

Carcinogenesis is a complex process triggered by changes in the expression of transcriptional regulators and proteins that are important for cell growth, angiogenesis, differentiation, cell cycle regulation, metastasis apoptosis, and invasion (13). Oncogenic characteristics such as dysregulated cell cycle regulation and apoptosis, enhanced metastasis, invasion, and angiogenic potential were identified as signified marks of the disease (28). Therefore, medicines should be efficient in treating cancer by approaching more than one pathway mentioned above (29). The use of a combination of silibinin and silymarin plays an important role in maintaining the disparity between apoptosis and cell survival by inhibiting the protein's implication in cell death and cell cycle progression. Furthermore, silymarin demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-metastatic effects by regulating specific proteins, which was previously reported (30). Figure 3 shows the anti-cancer behavior of silymarin in different tissues.

The anti-cancer potential of silibinin in different tissues (in vitro studies) is enlisted in Table 1.

| Type of Cancer | Cell Line | Concentration (µM) | Biological Action | Pathway | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | MCF-7 | 25 - 200 | Growth inhibition | PI3K/Akt | Suppression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | (31-33) |

| Lung cancer | A549 | 50 - 300 | Apoptosis | MAPK/ERK | Activation of MAPK/ERK pathway | (31, 34) |

| Colorectal cancer | HT-29 | 50 - 150 | Cell cycle arrest | Wnt/β-catenin | Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | (31, 34, 35) |

| Prostate cancer | LNCaP | 20 - 100 | Anti-androgenic | Androgen receptor | Downregulation of androgen receptor expression | (31, 34) |

| Pancreatic cancer | PANC-1 | 100 - 300 | Autophagy induction | mTOR | Inhibition of mTOR signaling pathway | (31, 34) |

| Liver cancer | HepG2 | 50 - 200 | Anti-metastatic | EMT | Suppression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition | (31, 34, 36) |

| Ovarian cancer | SKOV-3 | 25 - 100 | Angiogenesis inhibition | VEGF | Downregulation of VEGF expression | (31, 34) |

| Melanoma | A375 | 50 - 150 | Anti-invasive | MMP-2 | Inhibition of MMP-2 activity | (31, 34) |

| Gastric cancer | AGS | 25 - 200 | Apoptosis | NF-κB | Suppression of NF-κB signaling pathway | (28, 31, 34) |

| Bladder cancer | T24 | 50 - 300 | Cell cycle arrest | p53 | Activation of p53 signaling pathway | (31, 34) |

| Thyroid cancer | FTC-133 | 25 - 150 | Apoptosis | Bcl-2/Bax | Induction of apoptosis via modulation of Bcl-2/Bax | (31, 34) |

| Cervical cancer | HeLa | 50 - 200 | Anti-proliferative | JAK/STAT | Inhibition of JAK/STAT signaling pathway | (31, 34) |

| Esophageal cancer | TE-1 | 100 - 300 | Anti-migratory | Notch | Suppression of Notch signaling pathway | (31, 34) |

| Brain cancer | U87MG | 50 - 200 | Cell cycle arrest | Cyclin-dependent kinases | Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases | (31, 34) |

| Leukemia | K562 | 25 - 100 | Apoptosis | PI3K/Akt | Induction of apoptosis via PI3K/Akt pathway | (31, 34) |

3.1.1. Apoptosis

Cell death caused by apoptosis, also known as planned cell death, happens in various pathological and physiological situations and is considered a risk factor for cancer. The induction of apoptosis in cells predisposes them to lower proliferation by inhibiting the activation of AP-1 and NF-kB through the use of dietary phytochemicals (25, 37). Studies have shown that silymarin has anti-cancer properties because it induces apoptosis and inhibits the cell cycle in various malignancies (38). Figure 4 shows the impact of silymarin on apoptosis.

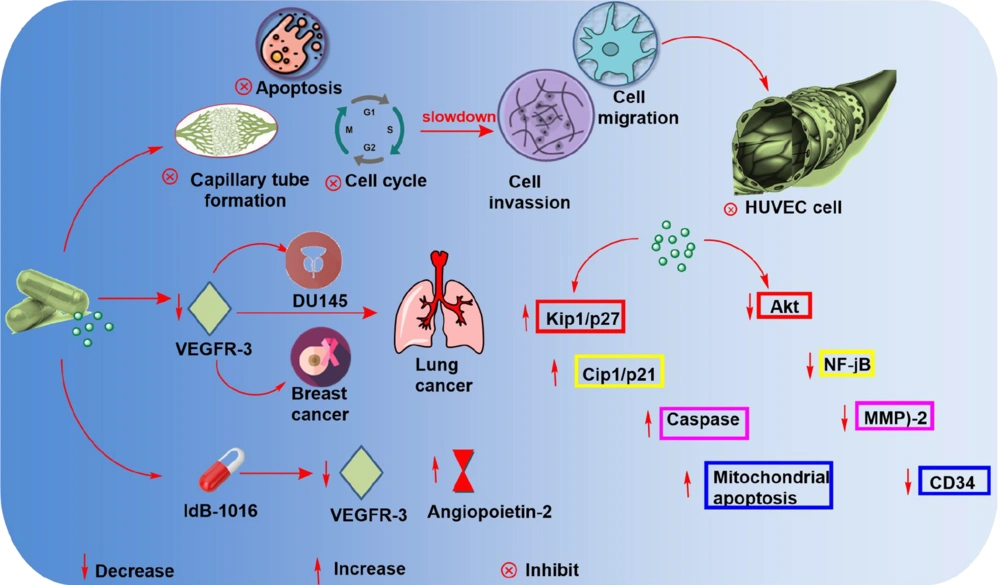

3.1.2.Anti-angiogenic

In cancer therapy, anti-angiogenic activity is the most effective method of combating the disease (6). Silymarin's anti-angiogenesis capability has been established in a variety of malignancies. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) grow and live less well when silymarin is used (37). The anti-angiogenic behavior of silymarin is illustrated in Figure 5.

3.1.3.Antifibrotic Activity

Fibrosis of the liver occurs as a consequence of hepatocyte damage, which activates Kupffer and hepatic stellate cells (HSC). Fibrogenesis is thought to begin with transforming HSC into myofibroblasts. Thus, liver fibrosis may result in modifying the liver's architecture, which can result in hepatic encephalopathy, hepatic insufficiency, and portal hypertension, among other complications (39). The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of silymarin is given in Figure 6A and B.

4. Conclusions

Silymarin exerts its anti-cancer effects via a variety of molecular pathways that have the potential to interfere with all phases of carcinogenesis. The anti-invasive and anti-metastatic, apoptosis, and anti-angiogenic behavior of silymarin, in particular, authorize its potential to be used as a preventative and therapeutic agent for more advanced and aggressive types of cancer. Silymarin regulates antioxidant defenses by blocking certain free radicals, producing enzymes, increasing the probity of the electron-transport chain of mitochondria, activating a variety of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, or through Nrf2 stimulation. It reduces inflammatory reactions by suppressing NF-kB pathways, which is an intriguing silymarin mechanism protective action. It appears quite plausible that the activation of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE (23) system, rather than direct ROS-eliminating action, may have a functional role in the therapeutic properties of silymarin. Silymarin treatment, when used in conjunction with other chemo-preventive drugs, was found to minimize chemotherapy toxicity in clinical investigations. The commercialization of silymarin and its bioactive components as drugs has the potential to stimulate further clinical research. Additionally, its formulation can effectively aid in the prevention and treatment of various medical disorders.