1. Background

Surgical site infection (SSI) is defined as infection occurring after 48 hours of any surgical intervention affecting incised superficial tissue, deep tissue, or organ spaces at or around the site of surgery. Surgical site infection includes the most common healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in surgical centers, accounting for up to 15% of HAIs. The analysis of 220 international studies of SSI in developing countries in the year 2010 showed the incidence of SSI as low as 0.4% to as high as 30.9%. The SSI rates in India vary from 6% to 38.7% (1-4).

Microbial contamination during pre, intra, or postoperative periods results in SSI due to either exogenous pathogens such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Pseudomonas acquired after breakthrough sterilization protocols from contaminated surgical instruments or operating room air contamination, or endogenous pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), coagulase-negative staphylococci, Enterococcus species, and E. coli opportunistically infecting wounds. Most pathogens causing SSI are multidrug-resistant (5-10).

Surgical site infection can result in fever, pain, discomfort, prolonged hospital stay, increased exposure to antimicrobials, and consequentially, increased healthcare costs. Meticulous surgical procedures of short duration taken place in a clean and hygienic environment and administration of prophylactic antimicrobials can decrease the risk of SSI. The risk of infection is higher during emergency surgery and minimal when the subcutaneous tissue is well perfused and oxygenated with no dead space. A large number of host factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypoxemia, hypothermia, leucopenia, long term use of steroids, nicotine, malnutrition, poor skin hygiene, etc. also can contribute to increasing the chances of SSI development (11, 12).

Periodic surveillance and feedback have been proven to reduce the rates of SSI. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US-CDC) have given fresh guidelines on SSI in 2017 after feedback from the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) (13).

2. Methods

This prospective study was conducted among all patients admitted to a 1000-bed tertiary-care teaching hospital in New Delhi for five months from May 2018 to September 2018, after approval of the Institutional Ethics and Scientific Committee. All good clinical practices and laboratory guidelines were observed. Patients staying less than 48 hours, testing positive for infections within 48 hours, or showing evidence of existing infections on admission were excluded.

2.1. Sample Collection, Transportation, and Processing

Samples were collected from the site of SSI such as the incision site and drain fluid following strict aseptic techniques. The samples were immediately transported to a microbiology lab for cultures on blood and MacConkey agars and incubated for 24 - 48 hours at 37°C. Organism identification and antimicrobial susceptibility were done through standard microbiology techniques employing routine bacteriological methods, Kirby Bauer Disk Diffusion method, and/or VITEK-2 Compact Automated Microbiology system. Non-repeat positive cultures with respective antibiograms were utilized for profiling of isolates and antimicrobial susceptibility. The patient’s demographic profile was noted from the patient’s charts/requisition form.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected from antibiogram patterns obtained through zone sizes from Kirby Bauer disk diffusion and/or minimal inhibitory concentration from the Vitek-2 compact automated microbiological system. The data were analyzed descriptively through Microsoft Excel and SPSS version 21 using appropriate tests.

3. Results

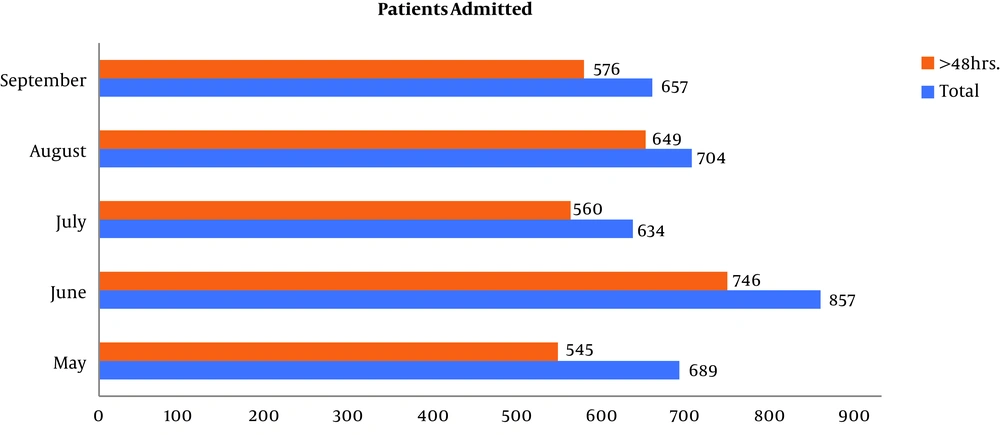

The analysis was done on the data of 3,541 patients admitted to both Gynecology-Obstetrics Ward and General-Surgical Ward of the hospital between 1, May 2018 and 30, September 2018 who underwent surgical interventions. Of them, 3,076 (86.87%, 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI): 85.7% to 87.96%) patients stayed in the hospital for more than 48 hours (Figure 1).

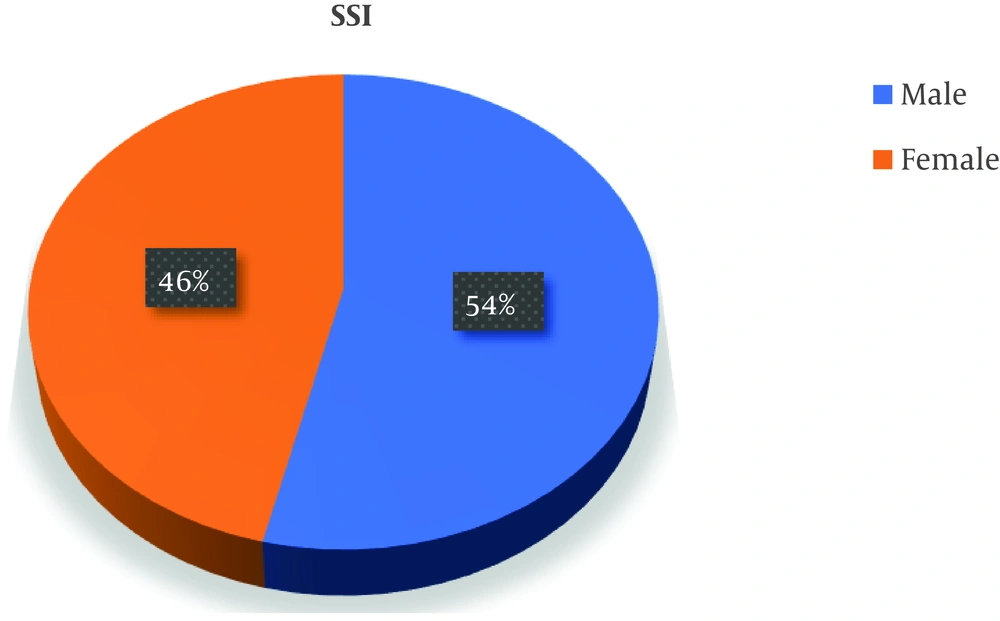

The common sterilization methods were autoclaving, plasma-sterilization, and ethylene oxide. Various antiseptics used for hand-hygiene were Povidone-iodine scrub solution, Savlon scrub solution, and soap. Cefotaxime 2 gm or cefoperazone 2 gm was used as a prophylactic antimicrobial agent one hour before surgery for uncomplicated cases for both general-surgery and gynecological procedures. The mean preoperative hospital stay and postoperative stay of the patients were 6.57 ± 12.7 and 19.25 ± 7.92 days, respectively. Besides, 43/80 (53.75%, 95% CI: 42.3% to 64.84%) were males, with a male to female ratio of 1.16:1 (Figure 2).

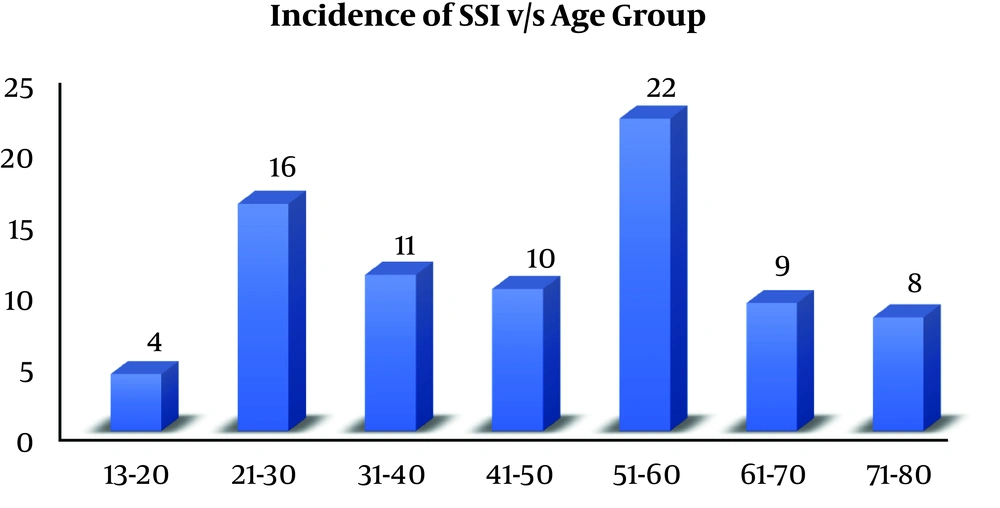

The overall rate of SSI was 80/3541 (2.26%, 95% CI: 1.81% to 2.82%). The highest incidence of SSI was noted in 51 - 60 years of age as 22/80 (27.5%, 95% CI: 18.4 to 38.8%) (Figure 3), while the lowest incidence was found in the age group of 13 - 20 years as 4/80 (5%, 95% CI: 1.6% to 12.9%).

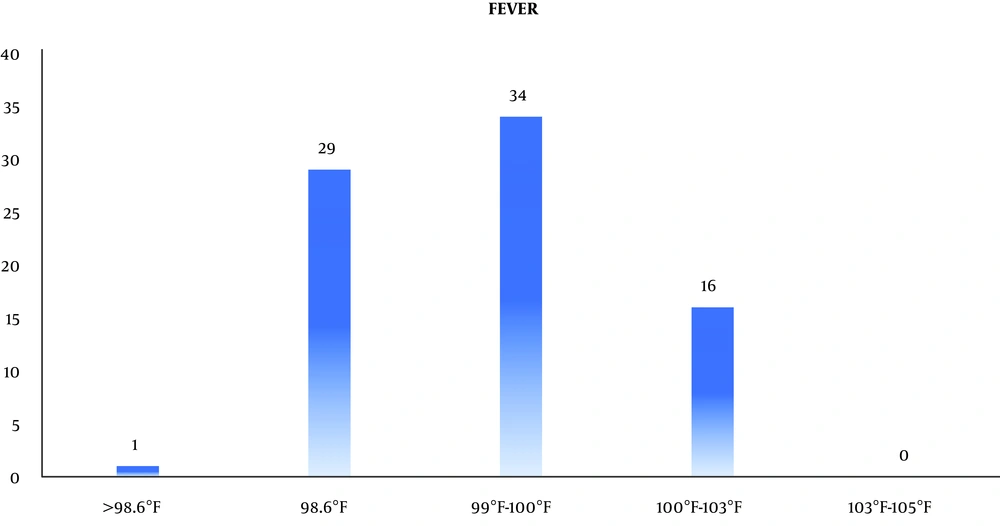

The mean duration of surgery was 4.5 hours. Besides, 23/80 (28.75%, 95% CI: 19.45% to 40.12%) patients had comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus [19/80 (23.75%, 95% CI: 15.25% to 34.81%)] and hypertension [15/80 (18.75%, 95% CI: 11.21% to 29.35%)]. Moreover, 34/80 (42.5%, 95% CI: 31.68% to 54.05%) patients presented with mild fever while 16/80 (20%, 95% CI: 12.2% to 30.74%) patients presented with body temperature between 100°F and 103°F. However, 29/80 (36.75, 95% CI: 26.01% to 47.82%) patients did not show any rise in temperature (Figure 4).

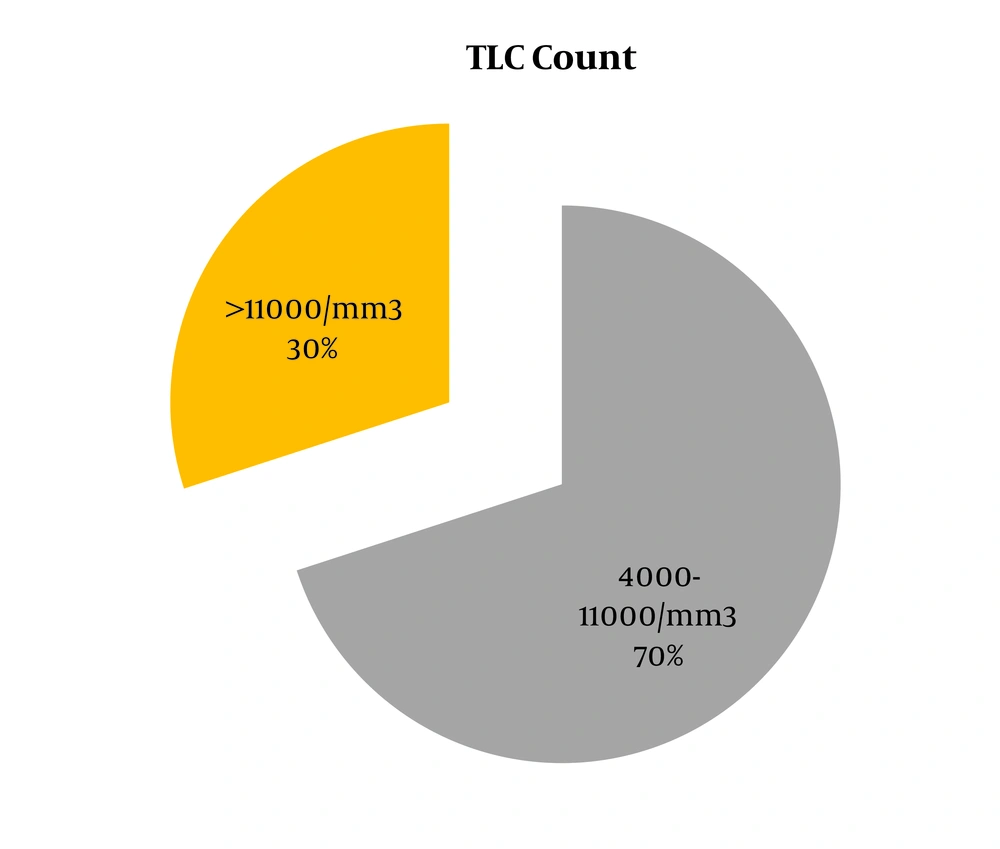

The WBC count was raised in 24/80 (30%, 95% CI: 20.52% to 41.42%) patients (Figure 5).

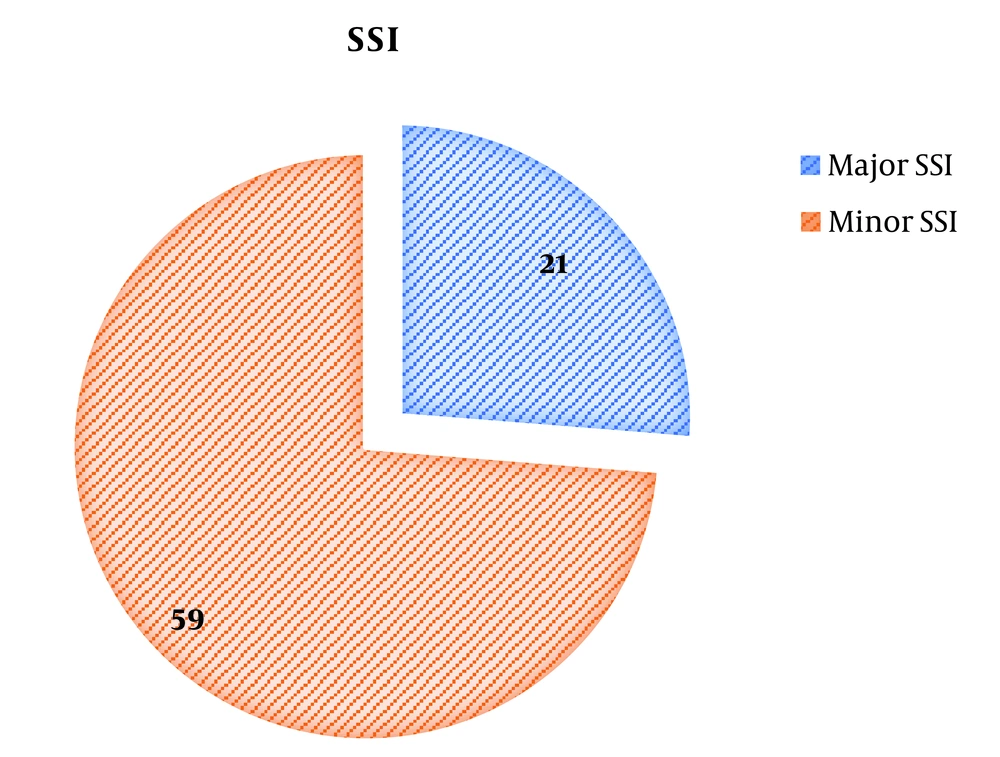

Moreover, 21/80 (26.25%, 95% CI: 17.33 to 37.48%) patients had pyrexia, increased leukocyte count, and tachycardia, thus falling under major SSI while remaining 59/80 (73.75%, 95% CI: 62.52 to 82.67) patients developed minor SSI (Figure 6).

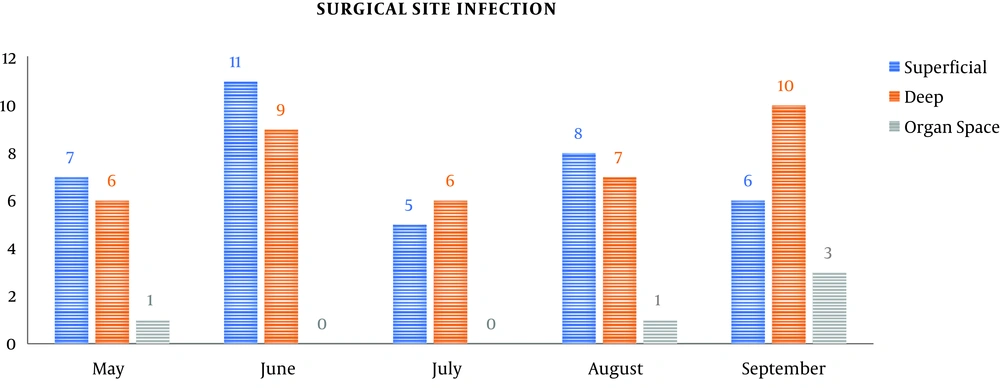

According to the CDC guidelines, superficial SSI was 37/80 (46.25%, 95% CI: 35.2% to 57.7%), deep SSI was 38/80 (47.5%, 95% CI: 36.34% to 58.9%), and organ space SSI was 5/80 (6.25%, 95% CI: 2.32% to 1.46%) (Table 1 and Figure 7).

| Month | Total | > 48 h | Superficial | Deep | Organ Space |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | 689 | 545 | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| June | 857 | 746 | 11 | 9 | 0 |

| July | 634 | 560 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| August | 704 | 649 | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| September | 657 | 576 | 6 | 10 | 3 |

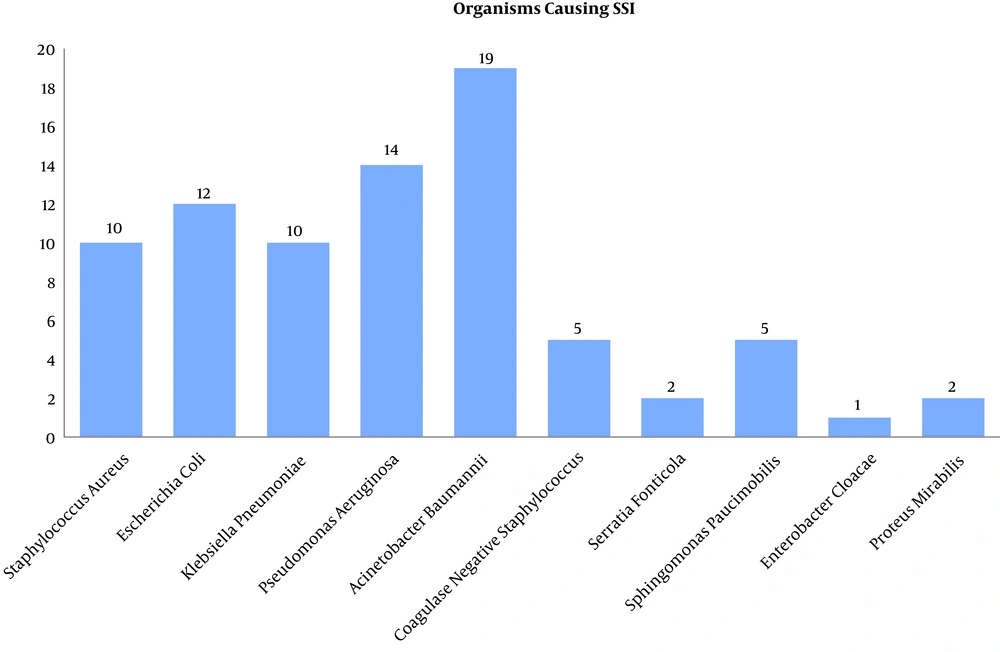

Gram-negative bacteria caused the highest rate of SSI as 65/80 (81.25%, 95% CI: 70.65% to 88.8%) wherein the most common pathogen was Acinetobacter baumannii as 19/80 (23.75%, 95% CI: 15.25% to 34.81%), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa as 14/80 (17.5%, 95% CI: 10.23% to 27.96%). Gram-positive bacteria accounted for only 15/80 (18.75%, 95% CI: 11.2% to 29.35%) episodes of SSI (Figure 8).

4. Discussion

The overall incidence of SSI in this 1000-bed tertiary-care hospital was 2.6%, which is comparable to the rates in other studies in other parts of the world and India, i.e., 2.5% to 38.7%. There was a marginal preponderance of male patients (54%) over female patients (46%) developing SSI. In some studies, female preponderance was reported, but sex is not a pre-determinant factor towards the risk of SSI. The highest incidence was observed in the 51 - 60 years’ age group. Studies have reported that the increasing age independently predicted an increased risk of SSI until the age of 65 years, while at ages ≥ 65 years, the increasing age independently predicted a decreased risk of SSI. The average duration of surgery was 4.5 hours among patients who developed SSI. Prolonged operation time, increased exposure to the operation theater air, prolonged anesthesia, prolonged trauma, and sometimes, excessive blood loss can increase the risk of SSI. Certain conditions like hyperglycemia and hypertension predispose an individual to SSI according to various studies (14-17).

Gram-negative bacilli were predominant causes of SSI, with Acinetobacter baumannii at the rate of 19/80 (23.75%), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with the rate of 14/80 (17.5%). This trend of gram-negative bacilli dominating gram-positive cocci has been observed in other studies (18-21). Acinetobacter species are oxidase-negative, opportunistic pathogens that have emerged as major causes of SSI in this setting. Acinetobacter has also been isolated from food (including hospital food), suctioning equipment, infusion pumps, sinks, pillows, mattresses, ventilator equipment, tap water, bed rails, stainless steel trolleys, humidifiers, soap dispensers, and other sources (22, 23).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen found in moist environments like hospital water systems. Multidrug-resistant strains are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. E. coli, accounting for 15% of SSI in this study, is a Gram-negative intestinal bacterium responsible for the endogenous infection. In other parts of the world such as Turkey (22.8%) and Brazil (15.3%), E. coli has been the most prevalent pathogen in SSI. Klebsiella pneumoniae as a gram-negative multidrug-resistant organism prevalent in hospital settings was responsible for 12.5% of SSI in this study (24-26).

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive coccus responsible for 12.5% of the total SSI in this study. It is accountable for a significant proportion of all SSI cases worldwide mainly affecting the skin and soft tissue. MRSA and vancomycin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) in hospital settings are difficult to treat (27). The study was limited by short duration and limited sample size; however, it can aptly serve a pilot study for planning multi-center prospective studies on SSI to delineate etiology, prognosis, and prevention strategies.

4.1. Conclusion

The rate of SSI in this study was comparable to the rates in India and the world. A pre-existing medical illness, prolonged operating time, and wound contamination strongly predispose to surgical site infection. Antimicrobial prophylaxis, hand-hygiene, reduced duration of surgery, and drain care are effective in reducing the incidence of SSI. Periodic surveillance of SSI can guide infection control committees in process surveillance.