1. Background

Heart failure (HF) is defined as a ‘clinical syndrome consisting of dyspnea, malaise, swelling, and/or decreased exercise capacity due to the loss of compensation for cardiac pumping function due to structural and/or functional abnormalities of the heart (1). Its incidence ranges from 100 to 900 cases per 100,000 people each year (2), and the prevalence is estimated to be two percent of the total population (3). HF is an important public health issue, and its prevalence, hospitalization rate, and costs increase over the years (4). It is responsible for 9.91 million years lost due to disability (YLDs). In addition, it’s estimated that the annual expenditure for HF is approximately 346 billion USD (5).

The incidence and prevalence of HF were not studied in military personnel, but some studies reported earlier onset of coronary artery disease in military personnel (6), which is a predisposing factor of HF (7).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), improving treatment adherence levels may be more effective than improving current treatment (8). Treatment adherence is the behavior of patients in taking medications, correcting diet, and ability to change lifestyle with the recommendations of the health care provider (8). Poor treatment adherence contributes to the worsening of disease conditions and leads to an increase in morbidity, mortality, direct and indirect health care costs, and disease burden (9). Evidence supports low treatment adherence in patients with chronic disease (10). Treatment adherence among patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) is 57 percent in 24 months period and decreases by 0.15 percent monthly, leading to low treatment adherence and CVD stage progression in the following years (11); While more complex treatment regimens require multiple drug assumptions, lifestyle modification, and diet changes were failed more (12). Most treatment adherence questionnaires can be used as an effective tool for improving care efficacy and treatment outcome (13).

Many studies identified several factors that influence treatment adherence of individuals, including patient's beliefs, health literacy, motivation, disease severity, psychiatric and cognitive condition, ethnicity, cultural differences, occupation, and changes in daily life. Cost, side effects, the total number of pills, and complexity in administration of medications also play a major role in determining treatment adherence (14-25).

To the best of our knowledge, currently, there is no specific instrument for measuring treatment adherence of HF patients in the literature review. The goal of this study was to develop and validate a novel instrument for measuring treatment adherence of HF patients. The results of this study can help health care providers and patients to detect reasons for treatment adherence failure in the early stages. This study also intends to assess the psychometric properties of the preliminary version of this questionnaire on military (Artesh) personnel and their families.

2. Objectives

To develop and validate a novel instrument for measuring treatment adherence of HF patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants, Sampling, and Design

This methodological psychometric exploratory study was conducted on military (Artesh) personnel and their family as key participants. Maximum variation sampling was used to reach a good representation of the community and reflect multidimensional aspects of HF within individuals with various perspectives, beliefs, behaviors, disease severities, etiologies, situations, and other differences, so forth (26). Participants were selected from both outpatient (private clinics) and inpatient (Madani hospital of Tabriz) settings. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before entering the study and after a comprehensive introduction to the study protocol. The inclusion criteria were (1) confirmed cases of HF; (2) adults older than 18 years old; (3) ability to understand and speak in Persian; (4) stable psychiatric condition; and (5) history of treatment for at least six months. Participants who refused to fill the form and those who partially filled the form were excluded from the study.

3.2. Phase I Item Generation

Items were generated by assessing multiple resources to reach acceptable coverage of various contents from literature reviews, patient field interviews, and expert opinions.

3.2.1. Step1-Literature Review

The research team reviewed 62 qualitative and quantitative self-reporting questionnaires using the following keywords: ‘treatment adherence and compliance’ and ‘medication adherence and compliance. The search was performed for the period after the 1990s to gather factors that influence treatment adherence.

3.2.2. Step2-Patient Field Interview

Patients were asked about difficulties that they face in performing treatment plans, including medication taking, lifestyle, and diet modifications.

First, a total of 30 semi-structured interviews were performed with 30 HF patients. Participants were selected from different age groups, socioeconomic status, literacy, disease severity, employment, and marital status to set a representative sample.

Second. The research team conducted a quick survey on 50 HF patients to explain three main reasons for their non-adherence.

3.2.3. Step 3-Expert Panel Opinion

An expert panel was formed to suggest additional items and summarize all items that were gathered in previous steps. The expert panel included four cardiologists, three cardiology nurses, one health education specialist, one psychiatrist, and one general practitioner, which had 3 - 26 years of experience in their careers.

3.3. Phase II Validity Analysis

3.3.1. Step 1-Content Validity

Content validity is a prerequisite for measuring other types of validities and has a critical role in the development of the new instrument. Content validity was assessed by measuring the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) (27).

CVR is a common method for measuring content validity, which is originally established by Lawshe. This ratio was used in various studies for quantitative assessment of content validity by collecting expert scores about the relevance of each item.

The research team invited three HF fellows, four cardiologists, one cardiology nurse, one health education professor, and one psychiatrist for CVR assessment. Experts scored the importance of each item using a three-item Likert (1 = Not necessary; 2 = Useful but not necessary; 3 = Essential). ‘Essential’ score was determined as acceptable. Scores were analyzed by the Lawshe formula, and items with CVR score lower than 0.62 were removed (28).

CVI is a method to assess the content representativeness of each item by expert scoring. Lynn provided a standard for acceptable CVI by the number of rating experts. Acceptable CVI in the 10 experts scoring condition is 0.78 (29).

The research team invited two HF fellows, four general cardiologists, two cardiology nurses, one health education professor, and one psychiatrist for CVI assessment. Experts scored the relevance of items using a four-item Likert (1 = Not relevant; 2 = Somewhat relevant; 3 = Highly relevant, 4 = Completely relevant). CVI was measured by dividing the number of experts, which gave scores of 3 and 4 into the total number of experts (30). Items with CVI score lower than 0.78 were revised.

3.3.2. Step 2-Face Validity

Face validity is an extent to measure which each research item concludes the conceptual domain of underlying content or not (31). Face validity of HFAQ was evaluated by measuring the impact score (IS) of each item by an expert panel consisting four HF fellows, three cardiologists, one cardiology nurse, one health education professor, and one psychiatrist. A five-item Likert was used (1 = Strongly appropriate; 2 = Appropriate but needs small changes; 3 = Appropriate but needs intermediate changes; 4 = Appropriate but needs significant changes; 5 = Inappropriate). Items with an impact score lower than 1.5 were removed (32).

3.3.3. Step 3-Construct Validity

The research team performed exploratory graph analysis (EGA), bootEGA, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the construct validity. Also, 360 individuals participated in this part of the study, eight participants refused to fill the forms, and 20 partially filled the forms, indicating a response rate of 92.2%. The demographic characteristics of participants are mentioned in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Item Generation Phase, N = 30 | Construct Validity, N = 332 | Reliability, N = 33 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 62.32 ± 10.22 | 60.92 ± 9.72 | 68.76 ± 11.08 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 14 (46.7) | 175 (52.7) | 18 (54.5) |

| Male | 16 (53.3) | 157 (47.3) | 15 (45.5) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 26 (86.7) | 277 (83.4) | 25 (75.6) |

| Single | 4 (13.3) | 55 (16.6) | 8 (24.4) |

| Educational status | |||

| Illiterate | 2 (6.7) | 23 (6.9) | 5 (15.2) |

| Below diploma | 6 (20.0) | 73 (22.0) | 8 (24.2) |

| Diploma | 10 (33.3) | 102 (30.7) | 9 (27.3) |

| Bachelors | 8 (26.7) | 102 (30.7) | 6 (18.1) |

| Master | 4 (13.3) | 31 (9.4) | 5 (15.2) |

| PhD | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Occupational status | |||

| Unemployed | 6 (20) | 96 (28.9) | 6 (18.2) |

| Employed | 12 (40.0) | 113 (34.0) | 15 (45.5) |

| Self-employed | 4 (13.3) | 48 (14.5) | 5 (15.1) |

| Retired | 8 (26.7) | 75 (22.6) | 7 (21.2) |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

EGA is an alternative and novel approach that determines complex relation between items and scorings to establish hypothetically acceptable constructs. Also, EGA is a better and more accurate tool to assess the dimensionality of questionnaires rather than traditional methods like exploratory factor analysis (33). Each item of the questionnaire, as a random variable, implies a node in the network psychometric perspective, while EGA identifies the dimension of constructs by investigating the connection of nodes and utilizing the inverse of variance-covariance matrix (34, 35). Hypothetically, each item of the questionnaire might correlate with other items, this connection is identified as edges or links. An edge indicates a partial correlation coefficient, which identifies the strength of association between nodes (36). A partial correlation network is interpreted using the walktrap algorithm, which analyzes distances via random walks (37). BootEGA with a parametric approach, as a complementary tool for assessing internal consistency, was utilized to evaluate the structural consistency and dimensionality of structures. In this method, EGA creates a network of nodes and edges and generates new replicate data until the desired number of bootstraps is reached (e.g., 500). The research team used descriptive statistics of EGA, such as median number, standard error, confidence interval of dimensions, lower and upper confidence interval around the median, and lower and upper quantile, to evaluate the stability of dimensions (38). CFA was utilized, and goodness-of-fit indices, such as chi-square, degree of freedom (df), P-value, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), were measured to confirm the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. The ratio of chi-square to df is the preferred measure to assess fitness between hypothesized model and data, which a ratio of two or lower was considered as a great fit (39). RMSEA lower than 0.08, CFI values higher than 0.9, and P-value lower than 0.05 were indicated as good fit standards (40).

3.4. Phase III Reliability Analysis

The reliability of HFAQ was assessed by measuring the Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Cronbach’s alpha. Thirty-three individuals were engaged randomly in reliability assessment, and the interval between test and re-test was two weeks. Cronbach’s alpha, which measures internal consistency, was used to evaluate construct reliability. Values higher than 0.9 were indicated as well, values in the range of 0.7 - 0.9 were indicated as adequate, and values lower than 0.7 were indicated as inappropriate internal consistency (41). ICC was used to assess the reproducibility and stability of data in the test-retest method, and values higher than 0.6 were implied as acceptable (42).

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee of AJA University of medical sciences before the commencement of the study. All participants were informed, and those who agreed to participate filled out the informed consent form. Participation in the study had no harm to participants, and all of them had the right to withdraw from any part of the study without taking any consequences. The collected information remained confidential, and the HFAQ questionnaire only focused on needed information.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was administered using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 26. Data of EGA was utilized using EGAnet package version 0.9.8; hence, CFA was analyzed by performing CFA Fit of EGA Structure code by R software version 4.1.2. The validity and reliability of HFAQ were determined by applying specific statistical methods, which are described in the following sections.

4. Results

4.1. Step 1-Item Generation Results

In the first step, 88 potential items were listed by literature review in three main domains of medication, lifestyle, and diet. In the second step, 24 potential items were listed by patient field interview, and finally, expert panel suggested 10 new potential items and gathered all the 122 items for generating HFAQ's item pool. Also, 11 items with similar themes were merged, 12 items were deleted due to lack of enough value in assessing treatment adherence of HF patients, and 13 items were removed because of low relevancy and suitability in measuring scale. Item pool with 86 items was generated with 45 medications, ten lifestyles, nine diet items, and 22 common items between these three categories. Item pool of HFAQ was categorized into four main domains and 15 sub-domains. The main domains were belief, behavior, barrier, and the patient-provider relationship. Sub-domains were understanding of disease and treatment, cognitive and psychiatric properties, self-management competency, outcome expectancies, situational perception, ethnicity, side effects/harms of medication, poly-pharmacy, occupation, changes in daily life, the complexity of treatment, availability of effective treatment, cost, support, medication-taking discipline, disease severity, stigma, and treatment satisfaction.

4.2. Step 2-Validity Results

4.2.1. Content Validity

All 86 items were scored by two separate expert panels to measure the CVR and CVI scores of each item. CVR score of items varied from -0.6 to 1. Also, 27 items had a score of 0.8, and 16 items were scored as 1; while 43 items with CVR scores lower than 0.62 were removed. CVI score of items varied in the range of 0.5 to 1. Also, 21 items had a score of 0.8, 14 items were scored 0.9, and 6 items were scored 1; while two items with a CVI score lower than 0.79 were revised.

4.2.2. Face Validity

The expert panel analyzed the face validity of the remained items (n = 43). The impact score of items was more than 1.5 and varied from 2.4 to 4.8. Six items had slight structural changes, and all of the items were understandable.

4.2.3. Construct Validity

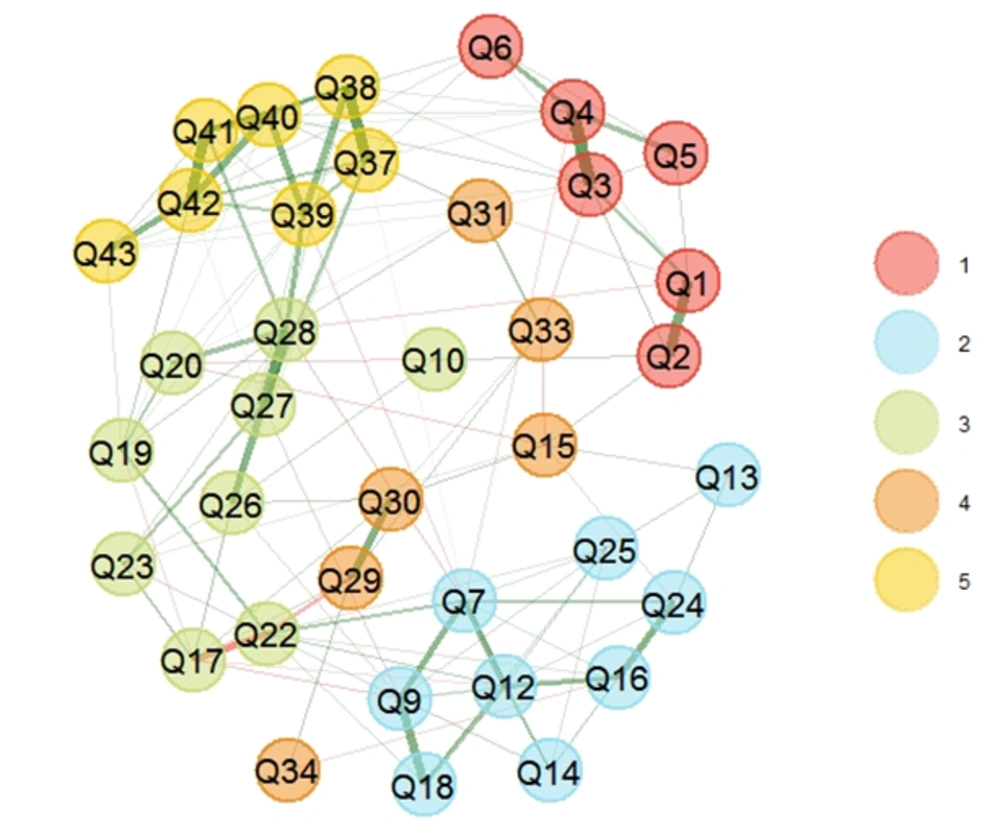

Data was collected from 332 questionnaires that were filled out, and 500 bootstraps were reached to assess the construct validity of the HFAQ. In the first step, EGA was conducted to specify questionnaire dimensions, which represented a five-factor model (Figure 1). The stability of constructs was evaluated by checking the descriptive statistics. Based on the results, the mean of the five dimensions mirrors the empirical EGA with a relatively narrow confidence interval (CI 95% [4.083, 5.916]).

Structural consistency was measured by assessing the dimensional stability of HFAQ items across all bootstrap replicate samples. Based on the results, the dimensional stability of constructs was 0.91, 0.81, 0.17, 0.23, and 1.0, respectively, which indicated significant instability in dimensions 3 and 4. Afterward, the research team clarified unstable items by investigating item stability values across each dimension in the replicate bootstrap samples (Appendix 2). Unstable items were reported as Q10, Q15, Q17, Q19, Q22, Q23, Q31, Q33, and Q34. These items were associated with their theoretical dimensions; however, they share a significant conceptual similarity, which forms a separate dimension. Multidimensional items can reduce the stability of dimensions; thus, the research team removed these items to reach good dimension consistency.

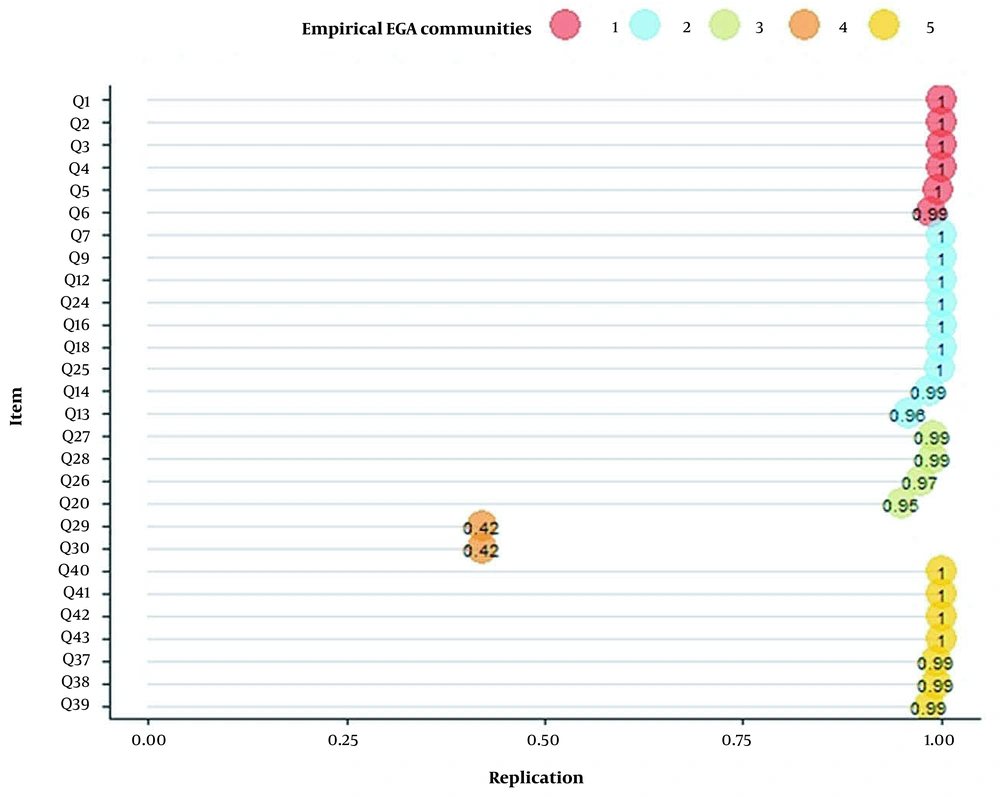

In the second step, EGA was conducted to specify dimensions after removing nine unstable items. EGA results represented a five-dimension model, in which construct 4 with two items (i.e., Q29 and Q30) had a replication value of 0.42 (Figure 2). The research team removed these items to reach good dimension consistency.

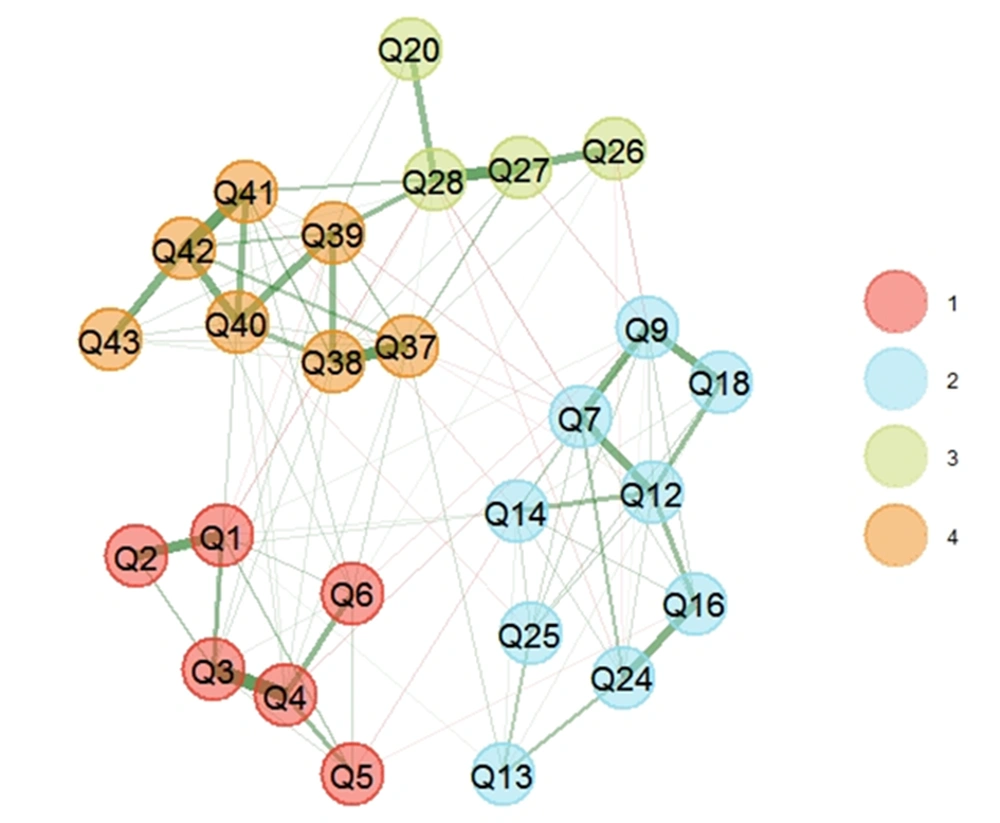

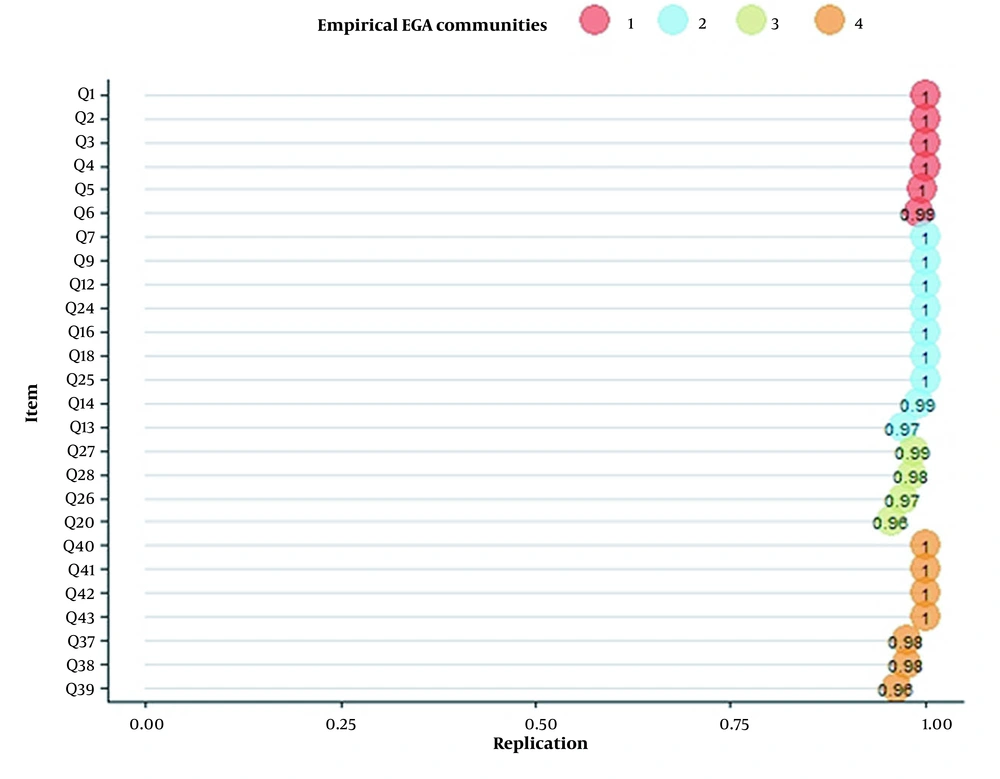

Finally, EGA was conducted after removing 11 items. EGA results represented a four-dimension model for HFAQ (Figure 3), as (C1)- Health Literacy, (C2)- Barriers, (C3)- Social and Economic, and (C4)- Patient-Provider Relationship. The number of items in constructs was 6, 9, 4, and 7 items, respectively. Based on the descriptive statistics of dimensions across all bootstrap replicate samples results, the mean of four dimensions mirrored empirical EGA with a relatively narrow confidence interval (CI 95% [3.769, 4.231]) (Table 2). Stability of items in constructs ranged from 0.96 to 1, which represented a good construct consistency (Figure 4).

| N Boots | Median Dim | SE Dim | CI Dim | Lower CI | Upper CI | Lower Quantile | Upper Quantile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 4 | 0.118 | 0.231 | 3.769 | 4.231 | 4 | 4 |

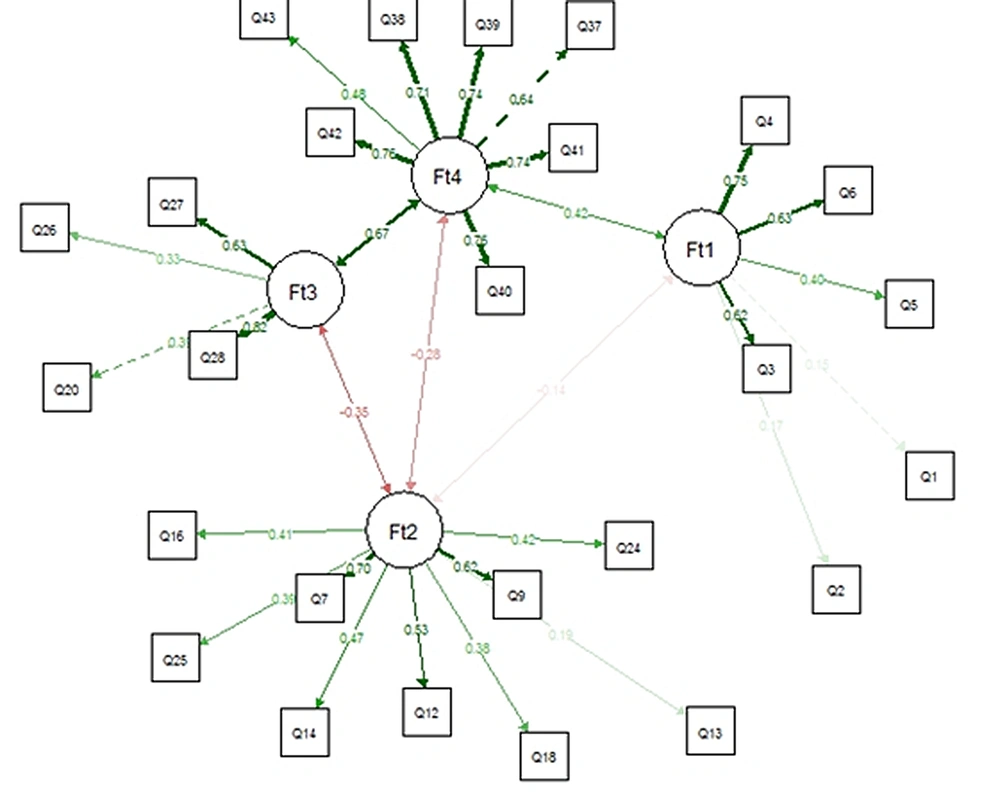

CFA was performed to assess the correlation of hypothesized model by measuring goodness-of-fit indices (Figure 5). The results are reported as χ2 = 535.657, df = 293, χ2/df = 1.828, P-value < .001, CFI = 0.851, and RMSEA = 0.050. Great fit to data was expressed by RMSEA, P-value, and Ratio of chi-square to df; hence, CFI was lower than 0.9, representing moderate fit to data.

4.3. Reliability Results

4.3.1. Step 1- Internal Consistency Results

Cronbach’s alpha of the 43-item final item pool was 0.58, which is lower than 0.7. The research team removed six items before the conduction of EGA. Final Cronbach’s alpha was assessed after the EGA results, representing a value of 0.73. Cronbach’s alpha of constructs was 0.70, 0.73, 0.60, and 0.86, respectively. Health literacy, barrier, patient-provider relationship constructs, and HFAQ entirely had acceptable internal consistency; however, social and economic constructs had moderate internal consistency.

4.3.2. Step 2- Stability Results

ICC of the entire questionnaire was 0.97, while ICC values of each construct were reported as 0.89, 0.94, 0.71, and 0.95, respectively. All ICC values were higher than 0.6, demonstrating good stability of HFAQ items and constructs over time.

5. Discussion

Heart failure is a major health problem for patients, their families, and health systems worldwide (43). Ageing of communities’ results in increasing prevalence and incidence of HF, which induces a severe burden on health systems (44). Improving treatment adherence could lead to better disease outcomes (45). To the best of our knowledge, HFAQ is the first questionnaire focused on assessing treatment adherence of HF patients.

Based on the results, all items were loaded into the patient-provider relationship, social and economic, health literacy, and barrier constructs. To the best of our knowledge, the acceptable value of internal consistency in the EGA method is controversial among studies. Generally, there is no established acceptable value; however, an expert panel can set a range according to the condition of each scale development procedure (38). Some studies defined 0.75 or above as an acceptable standard (46). The findings of this study indicated a frequency of 0.986 for bootstraps, which represents a high re-creating of the random re-occurrence of constructs.

Health literacy was one construct of HFAQ, which contains six items with dimensional stability of 0.9. Schonfeld et al. assessed the association between self-reported health literacy and treatment adherence by reviewing nine studies. Six studies reported significant and positive effects, while two studies reported positive but non-significant and one reported mixed results about the association between health literacy and treatment adherence, indicating the significant and principal importance of health literacy in measuring treatment adherence (47). Suhail et al. reported a significant association between health literacy and treatment adherence of patients with ischemic heart disease (48).

The patient-provider relationship was one of the constructs of this study with good stability. Wu et al. reviewed three general CVDs and three heart failure-specific studies to assess the importance of the patient-provider relationship and identified factors that affect the adherence of HF patients. Based on this study, both patients and physicians must have good relationships to reach acceptable treatment adherence (49). Many studies supported the robustness of this concept on treatment adherence of patients. Zschocke et al. developed the topical therapy adherence questionnaire in three domains, which “knowledge, communication, and relationship with a physician”, with seven items, were one of the constructs. This construct was considered to have a significant influence on treatment adherence, with item-total correlation ranged from 0.58 to 0.92 (50). Based on the HFAQ’s results, seven items were loaded in the patient-provider relationship construct with replication values ranging from 0.96 to 1.00, indicating the high stability of this construct (46).

WHO identified socioeconomic status as an important predictor of adherence and a risk factor for poor adherence, which needs to be improved by fundamental interventions? Also, socioeconomic factors were identified specifically as the underlying cause of poor adherence in hypertensive patients (8). Gast et al. (51) studied 21 systematic reviews to identify factors that influence the adherence of adults with chronic physical disease. This study reported a social gradient in treatment adherence behavior, and also socioeconomic status had a positive impact on adherence of CVD patients. The social and economic construct of HFAQ had four items, which represented 0.96 - 0.99 replication and 0.67 correlation with the patient-provider relationship construct. The results declared the important role of physician interventions in decreasing the consequences of low socioeconomic status on treatment adherence.

George et al. (23) identified influencing concepts of treatment adherence as two general constructs of belief and behavior; hence, factors that distort treatment adherence were called the ‘general concept of barriers’ (30). However, Matza et al. identified ‘barriers’ to treatment adherence as an independent construct (52). In the process of developing HFAQ, the research team gathered data from multiple domains of belief, behavior, and barriers. Similarly, EGA results categorized nine items with barrier concept to one construct; thus, the research team decided to consider the barriers of treatment adherence as a separate construct rather than a general concept.

Content and face validity of HFAQ was assessed by measuring CVR, CVI, and impact score. Forty-three items (50%) with a CVR score lower than 0.62 (Lawshe table limit for 10 examiners) were removed. Two items had a CVI score lower than 0.79, while the impact score of all items was more than 1.5. Dehghan Nayeri et al. developed a 35-items coronary artery disease treatment adherence scale. In this study, two items (3.6%) had a CVR score lower than 0.51 (Lawshe table limit for 14 examiners). All CVI values were higher than 0.79, while four items were removed due to the low impact score (53). The CVI value and impact scores of the two studies were similar, while in the process of developing HFAQ, more items were removed, which might be due to the higher number of items in the primary item pool or different expectancies and standards of expert examiners.

The reliability of HFAQ was assessed by measuring internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Cronbach's alpha was 0.73, and ICC was measured as 0.97. Ma et al. (54) developed a treatment adherence questionnaire for patients with hypertension, which Cronbach’s alpha was reported as 0.86 and ICC as 0.82. Both studies reached acceptable internal consistency due to Cronbach’s alpha value higher than 0.6 - 0.7 and acceptable test-retest reliability according to ICC value higher than 0.6.

5.1. Conclusions

HFAQ is the first treatment adherence questionnaire developed specifically for assessing treatment adherence of heart failure patients and is a valid and reliable 26-item questionnaire which intends to evaluate treatment adherence in three main contexts of medication, physical activity, and diet. Treatment adherence factors were extracted from three conceptual frameworks of belief, barrier, and behavior, which led to the development of four dimensions of health literacy, social and economic, barrier, and the patient-provider relationship. HFAQ can be used as an intervention for improving treatment outcomes and disease burden. HFAQ was developed as a primary tool for emphasizing the importance of treatment adherence among heart failure patients as a chronic disease. Eventually, the research team hopes that the findings will help other researchers to develop more comprehensive and advanced treatment adherence questionnaires for heart failure patients.

5.2. Limitations

The limitations of this study can be classified as follow. Items were generated using the literature review, focus group discussion with 30 patient, and expert opinions (n = 10). Increasing the number of patients and experts would help researchers to achieve a richer item pool. Also, gathering data from friends and family of patients can be helpful. The HFAQ was developed to assess treatment adherence of military (Artesh) personnel and their families, while developing a general questionnaire for heart failure patients requires a wide diversity of participants in beliefs, ethnicity, occupation, socioeconomic level, and health literacy fields. A small sample of participants was gathered for questionnaire development, while implementing HFAQ on more patients may provide different results.