1. Background

Facing death is one of the most challenging emotional experiences and an inevitable part of life (1, 2). Advances in medical science and technology, combined with an aging population and an increase in patients with cancer and chronic diseases, have led to more frequent encounters between nurses and dying patients (3). Dying patients often face complications such as fear of death, pain intolerance, and the deterioration of physical and mental health (2). Managing uncomfortable symptoms, meeting the complex care needs of patients and their families, and providing psychological and spiritual support are fundamental components of end-of-life care (3). The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes every individual's right to receive end-of-life care (4).

End-of-life care is a sensitive and integral part of nursing that requires communication skills such as empathy, critical decision-making abilities, and specialized, comprehensive care (5-7). Many nursing students experience caring for dying patients and their families during their clinical training (2, 6). Developing clinical competence in end-of-life care is a significant professional challenge (8) and one of the most sensitive, difficult, complex, and stressful experiences for nursing students (2). During clinical education, nursing students have reported feelings of unpreparedness for providing care, a desire to distance themselves from the patient, anxiety, fear of assuming the caregiver role, fear of touching a corpse (5, 7), and avoidance behaviors when facing dying patients (9).

The quality of end-of-life care is greatly influenced by attitudes toward the care of dying patients (10). Attitude refers to an individual’s evaluation of a subject, shaped by personal experiences and influenced by emotions and actions (9). A positive attitude and mental preparedness are essential for providing effective end-of-life care (1, 2, 6). The attitudes of nursing students toward end-of-life care are influenced by personal and professional experiences, interactions with patients and families, moral principles, societal norms, culture, religion, and training received (4, 10). These attitudes can affect the moral, humanistic, and quality aspects of patient care (1, 3, 5-7). A positive attitude can also facilitate critical decision-making, foster effective communication with patients and families, and help preserve human values and patient rights during challenging end-of-life situations (2, 3). Studies have shown that nursing students' attitudes toward end-of-life care range from positive to negative (9, 11, 12).

In Iran, end-of-life care is predominantly provided in hospital settings, as there are no specialized centers dedicated to this type of care. Changing family dynamics and an aging population have increased the need for end-of-life care in hospitals. Despite recent efforts to prioritize end-of-life care within nursing, evidence suggests that nursing students often lack confidence when caring for patients in these critical situations. Given the pivotal role nurses play in this domain, it is essential for students to commit to learning and cultivate positive attitudes toward end-of-life care (2, 9, 13).

End-of-life care is a critical aspect of nursing within healthcare systems, with attitudes toward this care significantly influencing the quality of services provided. Assessing nursing students' attitudes regarding end-of-life care offers insights into the effectiveness of their curriculum in fostering positive perspectives.

2. Objectives

Consequently, researchers undertook a study in 2023 to explore the attitudes of Iranian nursing students toward end-of-life care at the Islamic Azad University's Karaj branch.

3. Methods

A cross‐sectional study.

3.1. Setting

The research was conducted at the Faculty of Nursing, Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch, located in Alborz Province, Iran.

3.2. Participants

Sampling was conducted using a convenience method. The inclusion criteria for the study encompassed nursing students enrolled at the Islamic Azad University of Karaj, second-semester or later, who voluntarily participated in the study. The exclusion criterion was failing to complete the questionnaire within the specified time or providing incomplete responses. Out of 270 nursing students, 40 first-semester students were excluded from the study. A total of 230 students met the inclusion criteria. Among the 216 completed questionnaires, 16 were excluded from analysis due to incomplete information. Ultimately, data from 200 questionnaires were analyzed (N = 200, effective response rate: 86.95%).

3.3. Instruments

The data were collected using a demographic form and the Frommelt Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale form B-I (FATCOD-BI). The FATCOD-BI, developed by Frommelt et al. in 1991, comprises 30 Likert-type items where participants rate their agreement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The subscales include fear/malaise, care of the family, communication, family as caring, relationships, and active care. Of the 30 items, 15 are positively worded, while the remaining 15 are negatively worded. For the negative items, the ratings are reversed during scoring. Total scores range from 30 to 150, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude toward caring for dying patients. A score below 90 is considered an unfavorable attitude, whereas a score above 90 reflects a favorable attitude (11).

3.4. Validity and Reliability

The Frommelt Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale form B-I demonstrated good internal consistency and reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.76 (14). Before data collection, the researchers reassessed the validity and reliability of the FATCOD-BI scale, and the calculated Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.86, confirming its reliability.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Sciences Faculty, Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch, under the ethics code IR.IAU.K.REC.1401.144. Participants were thoroughly informed about the study's objectives, and their participation was entirely voluntary. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and confidentiality was strictly maintained throughout the research. The questionnaires were completed anonymously, and participants were assured that they would face no risks during the study.

3.6. Data Collection

Data collection took place from April 24, 2023, to June 10, 2023. A trained researcher oversaw the data collection process. The researcher provided a thorough explanation of the study's purpose, inclusion criteria, and instructions for completing the questionnaire to all participants. The questionnaires were completed using a self-administered method, and participants were given ample time to complete them.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 26, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and ANOVA.

4. Results

The effective response rate was 86.95%. The mean age of the students was 21.1 years (SD = 4.21, range 19 - 32 years). The highest frequency of ages was observed between 20 and 22 years. Most of the students were female (74.5%) and single (91%). The majority were in their 4th and 5th semesters (37%). Additionally, 26.5% of the participants had encountered a dying patient, while 15.5% had encountered a dying person. Of those encounters, 13.5% occurred during clinical training, and 64.5% of the students had not received any training in the care of dying patients (Table 1).

| Variables and Categories | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| < 20 | 69 (34.5) |

| 20 - 21 | 44 (22) |

| 21 - 22 | 44 (22) |

| > 22 | 43 (21.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (25.5) |

| Female | 149 (74.5) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 182 (91) |

| Married | 18 (9) |

| Religion | |

| Muslim | 200 (100) |

| Semester | |

| 2, 3 | 64 (32) |

| 4, 5 | 74 (37) |

| 6 - 8 | 62 (31) |

| Encounter with dying patients | |

| No | 147 (73.5) |

| Yes | 53 (26.5) |

| Setting of encounters with dying patients | |

| Clinical training | 27 (13.5) |

| Outside clinical setting | 26 (13) |

| Number of dying patients encountered | |

| None | 147 (73.5) |

| 1 | 31 (15.5) |

| > 1 | 22 (11) |

| Received training on care of dying patients | |

| No | 129 (64.5) |

| Yes | 71 (35.5) |

According to Table 2, the highest mean score was associated with item 16: "Families need emotional support to accept the behavior changes of the dying person" (M = 4.03, SD = 0.74). Conversely, the lowest mean score was associated with item 8: "I would be upset when the dying person I was caring for gave up hope of getting better" (M = 2.31, SD = 0.94).

| FATCOD-BI subscale/Items | Values | SD | DA | Un | A | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Giving care to the dying person is a worthwhile experience. | 3.8 ± 0.93 | 7 (3.5) | 9 (4.5) | 42 (21) | 100 (50) | 42 (21) |

| 2- Death is not the worst thing that can happen to a person. | 3.46 ± 1.15 | 10 (5) | 40 (20) | 34 (17) | 79 (39.5) | 37 (18.5) |

| 3- I would be uncomfortable talking about impending death with the dying person. | 2.51 ± 1.12 | 11 (5.5) | 34 (17) | 36 (18) | 85 (42.5) | 34 (17) |

| 4- Caring for the patient’s family should continue throughout the period of grief and bereavement. | 3.59 ± 1.04 | 7 (3.5) | 27 (13.5) | 43 (21.5) | 86 (43) | 37 (18.5) |

| 5- I would not want to care for a dying person. | 3.06 ± 1.07 | 19 (9.5) | 50 (25) | 70 (35) | 47 (23.5) | 14 (7) |

| 6 -The non-family caregivers should not be the one to talk about death with the dying person. | 3.21 ± 1.06 | 16 (8) | 79 (39.5) | 50 (25) | 42 (21) | 13 (6.5) |

| 7- The length of time required to give care to a dying person would frustrate me. | 3.09 ± 1.06 | 13 (6.5) | 71 (35.5) | 50 (25) | 53 (26.5) | 13 (6.5) |

| 8- I would be upset when the dying person I was caring for gave up hope of getting better. | 2.31 ± 0.94 | 7 (3.5) | 17 (8.5) | 37 (18.5) | 109 (54.5) | 30 (15) |

| 9- It is difficult to form a close relationship with the dying person. | 2.59 ± 1.01 | 8 (4) | 37 (18.5) | 38 (19) | 100 (50) | 17 (8.5) |

| 10- There are times when death is welcomed by the dying person. | 3.41 ± 0.83 | 5 (2.5) | 16 (8) | 85 (42.5) | 80 (40) | 14 (7) |

| 11- When a patient asks, “Am I dying?” I think it is best to change the subject to something cheerful. | 3.75 ± 0.94 | 43 (21.5) | 88 (44) | 49 (24.5) | 16 (8) | 4 (2) |

| 12- The family should be involved in the physical care (feeding, personal hygiene) of the dying person. | 3.19 ± 0.89 | 3 (1.5) | 44 (22) | 76 (38) | 66 (33) | 11 (5.5) |

| 13- I would hope the person I’m caring for dies when I am not present | 2.75 ± 0.99 | 7 (3.5) | 37 (18.5) | 75 (37.5) | 60 (30) | 21 (10.5) |

| 14- I am afraid to become friends with a dying person. | 2.98 ± 0.92 | 6 (3) | 57 (28.5) | 73 (36.5) | 55 (27.5) | 9 (4.5) |

| 15- I would feel like running away when the person actually died. | 2.79 ± 1.04 | 11 (5.5) | 41 (20.5) | 62 (31) | 68 (34) | 18 (9) |

| 16- Families need emotional support to accept the behavior changes of the dying person. | 4.03 ± 0.74 | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 28 (14) | 117 (58.2) | 49 (24.5) |

| 17- As a patient nears death, the non-family caregiver should withdraw from his or her involvement with the patient. | 3.86 ± 0.88 | 3 (1.5) | 14 (7) | 33 (16.5) | 107 (53.5) | 43 (21.5) |

| 18- Families should be concerned about helping their dying member make the best of his or her remaining life. | 3.35 ± 0.93 | 18 (9) | 76 (38) | 68 (34) | 34 (17) | 4 (2) |

| 19- The dying person should not be allowed to make decisions about his or her physical care. | 3.06 ± 0.95 | 14 (7) | 49 (24.5) | 79 (39.5) | 51 (25.5) | 7 (3.5) |

| 20- Families should maintain as normal an environment as possible for their dying member. | 3.85 ± 0.76 | 1 (0.5) | 12 (6) | 34 (17) | 122 (61) | 31 (15.5) |

| 21- It is beneficial for the dying person to verbalize his or her feelings. | 3.80 ± 0.82 | 3 (1.5) | 8 (4) | 49 (24.5) | 106 (53) | 34 (17) |

| 22- Care should extend to the family of the dying person. | 3.85 ± 0.87 | 6 (3) | 5 (2.5) | 42 (21) | 106 (53) | 41 (20.5) |

| 23- Caregivers should permit dying persons to have flexible visiting schedules. | 3.81 ± 0.85 | 3 (1.5) | 15 (7.5) | 32 (16) | 117 (58.5) | 33 (16.5) |

| 24- The dying person and his or her family should be the in-charge decision makers. | 3.31 ± 0.91 | 6 (3) | 30 (15) | 74 (37) | 76 (38) | 14 (7) |

| 25- Addiction to pain relieving medication should not be a concern when dealing with a dying person. | 3.29 ± 0.99 | 5 (2.5) | 40 (20) | 68 (34) | 65 (32.5) | 22 (11) |

| 26- I would be uncomfortable if I entered the room of a terminally ill person and found him/her crying. | 2.43 ± 1.06 | 11 (5.5) | 25 (12.5) | 33 (16.5) | 101 (50.5) | 30 (15) |

| 27 -Dying persons should be given honest answers about their condition. | 3.86 ± 0.82 | 3 (1.5) | 9 (4.5) | 38 (19) | 113 (56.5) | 37 (18.5) |

| 28- Educating families about death and dying is not a non-family caregiver’s responsibility. | 3.29 ± 0.98 | 15 (7.5) | 80 (40) | 62 (31) | 34 (17) | 9 (4.5) |

| 29- It is possible for non-family caregivers to help patients prepare for death. | 3.52 ± 0.93 | 5 (2.5) | 19 (9.5) | 58 (29) | 102 (51) | 16 (8) |

| 30- Family members who stay close to a dying person often interfere with the professional’s job with the patient. | 2.90 ± 1.03 | 18 (9) | 76 (38) | 68 (34) | 34 (17) | 4 (2) |

Abbreviation: FATCOD-BI, Frommelt Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale form B-I.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

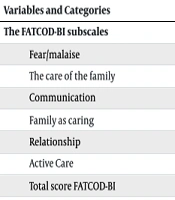

The mean and standard deviation of the FATCOD-BI scores were 98.76 (SD = 9.91), with a range of 74 to 138. The mean and standard deviation for the subscales are detailed in Table 3. Based on the cutoff points, 85% of participants demonstrated a favorable attitude toward caring for dying patients (total score > 90).

| Variables and Categories | Minimum-Maximum | Mean ± Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| The FATCOD-BI subscales | ||

| Fear/malaise | 14 - 45 | 27.16 ± 4.86 |

| The care of the family | 5 - 15 | 11.44 ± 1.94 |

| Communication | 9 - 30 | 19.97 ± 3.22 |

| Family as caring | 6 - 15 | 10.05 ± 1.64 |

| Relationship | 10 - 24 | 17.25 ± 2.17 |

| Active Care | 8 - 20 | 12.88 ± 1.95 |

| Total score FATCOD-BI | 74 - 138 | 98.76 ± 9.91 |

Abbreviation: FATCOD-BI, Frommelt Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale form B-I.

According to Table 4, a statistically significant difference was observed in the mean scores of nursing students' attitudes toward end-of-life care based on gender (P = 0.036), semester (P = 0.027), and prior training on the care of dying patients (P = 0.037). However, no statistically significant differences were found concerning age, marital status, exposure to a dying patient, the place of exposure to a dying patient, or the number of dying patients (P > 0.05).

| Variables and Categories | Mean ± Std. Deviation | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | F = 0.931; P = 0.427 | |

| < 20 | 99.66 ± 10.20 | |

| 20 - 21 | 99.88 ± 10.65 | |

| 21 - 22 | 97.02 ± 10.37 | |

| > 22 | 97.93 ± 8.01 | |

| Gender | T = 2.116; P = 0.036 | |

| Male | 101.27 ± 13.21 | |

| Female | 97.89 ± 8.38 | |

| Marital status | T = 0.839; P = 0.403 | |

| Single | 98.94 ± 10.09 | |

| Married | 96.88 ± 7.92 | |

| Semester | F = 3.686; P = 0.027 | |

| 2, 3 | 96.12 ± 8.03 | |

| 4, 5 | 99.43 ± 10.17 | |

| 6 - 8 | 100.67 ± 10.26 | |

| Encounter with dying patients | T = 0.392; P = 0.696 | |

| No | 98.92 ± 9.76 | |

| Yes | 93.30 ± 10.39 | |

| Setting of encounters with dying patients | T = -0.266; P = 0.791 | |

| Clinical training | 97.92 ± 7.31 | |

| Outside clinical setting | 98.69 ± 12.99 | |

| Number of dying patients encountered | F = 1.465; P = 0.241 | |

| None | 97.70 ± 10.42 | |

| 1 | 101.85 ± 10.84 | |

| > 1 | 94.37 ± 8.64 | |

| Received training on care of dying patients | T = -2.105; P = 0.037 | |

| No | 97.67 ± 8.64 | |

| Yes | 100.73 ± 11.69 |

5. Discussion

In our study, the mean FATCOD-Form BI score was 98.76 (SD = 9.91), which was higher than the scores reported by Zahran et al. (98.1, SD = 9.2) and Zulfatul et al. (93.83, SD = 5.96) (9, 15). However, it was lower than those observed in studies by Zhang et al. (99.04, SD = 7.71) and Younis et al. (102.7, SD = 11.2) (16, 17). Notably, 85% of nursing students in our study exhibited a positive attitude toward end-of-life care (score > 90), consistent with findings by Zahran et al. and Pérez-de la Cruz et al. (2, 9). Conversely, Paul et al. found that only 39% of Indian nursing students had a positive attitude in this domain, and Xu et al. reported moderate attitudes among students (18, 19). Furthermore, Jafari et al. observed negative to neutral attitudes (12). These variations could be attributed to cultural, religious, and societal differences in perceptions of death and caring for the dying.

Despite the lack of specialized end-of-life care training in our curriculum, students still exhibited positive attitudes. This could be influenced by religious and cultural factors. All nursing students in this study identified as Muslim, and Islamic teachings emphasize observing human and moral values, serving others, preserving life, accepting death as a natural part of existence, and believing in the afterlife. These principles may have contributed to the positive attitudes observed in this study (7, 19).

Interestingly, male students in our study demonstrated a more positive attitude toward end-of-life care compared to their female counterparts. This contrasts with Zahran et al., who reported that female nursing students had a more positive attitude in this domain (9). Additionally, studies by Younis et al., Zhang et al., Sáez-Alvarez et al., and Zulfatul A'la et al. found no significant relationship between gender and nursing students' attitudes toward end-of-life care (8, 15-17). Female students might experience stronger negative emotions when faced with dying patients, potentially impacting their attitudes toward end-of-life care. Providing additional education and opportunities for female nursing students to engage with terminally ill patients in hospital settings could help improve their attitudes in this area.

In this study, nursing students in higher semesters demonstrated a more positive attitude toward end-of-life care. This finding aligns with those of Zahran et al., Alwawi et al., Dimoula et al., and Zulfatul A'la et al., suggesting that as students progress academically, they gain more knowledge and experience regarding end-of-life care, which positively influences their attitudes (4, 9, 15, 20). Conversely, Ferri et al. did not find a correlation between academic progression and attitudes toward end-of-life care (11). Similarly, Younis et al. reported that third-year students exhibited a more positive attitude compared to fourth-year students (17). The evidence indicates that increased awareness through academic learning and clinical exposure to critically ill or dying patients contributes to improved attitudes toward end-of-life care.

In the present study, nursing students who had received training on caring for dying patients exhibited a more positive attitude toward end-of-life care. This finding is consistent with Younis et al., who found that education about end-of-life care positively influenced attitudes (17). Conversely, Ferri et al. and Zulfatul A'la et al. reported no significant correlation between nursing students’ attitudes and their receipt of education on the subject (15). Nevertheless, the results of the present study underscore the importance of specialized training in improving nursing students’ attitudes toward end-of-life care.

This study had several limitations. The cross-sectional design might not fully capture the dynamic evolution of students’ attitudes toward end-of-life care over their academic journeys. Longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into these changes over time. Furthermore, reliance on self-reported questionnaire responses may have led participants to provide socially desirable answers, potentially affecting data authenticity. The use of non-random sampling limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should explore how end-of-life care education influences both the attitudes and practical competencies of nursing students.

5.1. Conclusions

The attitude of nursing students toward end-of-life care was positive. This positive attitude was influenced by factors such as the level of education, gender, and training received. Aligning nursing education with real-world professional demands is essential to bridge the theoretical-practical gap. This finding emphasizes the need for curriculum planners and nursing education policymakers to integrate comprehensive end-of-life care modules into undergraduate nursing programs.