1. Background

Women naturally experience three physiological events in their life cycle and stages of growth: Menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause (1). Menstruation is one of the stages of puberty in the development of women (2). During these phases, women’s mental and physical health can transition into new physiological and psychological states. Therefore, the different stages of these changes can be considered central to every woman's mental well-being and social adjustment (1).

The normal duration of the menstrual cycle is 21 to 35 days, consisting of three phases: The follicular phase, ovulation, and the luteal phase (3). During this period, fluctuations in sex hormones significantly affect the entire body, leading to changes in physical, mental, and emotional functioning (4).

Primary dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation) refers to painful contractions of the lower abdomen and uterus (5). Dysmenorrhea is the most common menstrual disorder complaint among women and young girls (6), often accompanied by mood disturbances and pain that begin just before or during menstruation (7, 8). Menstrual pain is caused by an abnormal increase in the production of vasoactive prostaglandins in the endometrium (9, 10). Prostaglandins facilitate the expulsion of the endometrium, leading to uterine contractions (11, 12).

Based on pathophysiology, dysmenorrhea is classified as primary or secondary (13). Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as painful, spasmodic cramping in the lower abdomen just before or during menstruation, in the absence of any detectable macroscopic pelvic pathology (14). Secondary dysmenorrhea, on the other hand, is associated with identifiable pathological conditions, such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, fibroids (myomas), and pelvic inflammatory disease, and can onset at any time (13).

Women with primary dysmenorrhea report that menstruation negatively affects their quality of life (15). Pain is one of the main factors contributing to a reduced quality of life. Yoga has been shown to improve the quality of life for women with primary dysmenorrhea, significantly alleviating physical pain and discomfort, improving sleep, concentration, and emotional well-being, enhancing social relationships, boosting work capacity, and increasing energy levels (16, 17).

Yoga alleviates pain and sympathetic responses, coordinates the functioning of the endocrine system, and ultimately reduces physical pain while improving overall quality of life (16, 18). Pain relief remains the primary focus in the treatment of menstrual pain. Previous studies indicate that yoga reduces menstrual pain by decreasing the production of prostaglandins and mitigating myometrial ischemia through its effects on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system (19).

Yoga increases the pain threshold by enhancing endorphin secretion in the brain (20). Regular yoga exercises lead to physiological and functional improvements, playing an important role in central nervous system processing, peripheral nerve function, and the body’s natural response to environmental stimuli (21).

Yoga is recognized as a form of mind-body medicine and is classified by the National Institutes of Health as a type of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (22). Many researchers identify changes in lumbar arch size as a significant factor in chronic back pain (23). One of the common causes of back pain in women, especially during menstruation, is an increased curvature of the lumbar arch, or hyperlordosis (24). Increased concavity in the posterior lumbar spine region is a common complication, with the excessive type referred to as lumbar hyperlordosis (23).

Since trunk muscles play a vital role in maintaining proper body control and spinal posture, women with weak trunk muscle endurance are more prone to back pain (25). Recent research supports the effectiveness of yoga in achieving better physical posture and muscle flexibility (26). By emphasizing mindfulness during yoga asanas, this practice has been found to facilitate faster improvements in physical functions. Many studies have reported the effectiveness of yoga in alleviating distress and menstrual pain (27-30).

Today, other treatment methods are often based on clinical experiences that aim to reduce the prevalence and severity of menstrual symptoms, though the mechanisms may remain unclear. Regular physical exercise has demonstrated significant health benefits (31). Considering the importance of yoga as a low-cost complementary medical method, further investigation and attention are needed, particularly for sports science specialists, to optimize therapeutic exercise methods. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effect of yoga exercises on primary dysmenorrhea in women, including its impact on pain, menstrual distress, and lumbar hyperlordosis.

2. Objectives

The researcher in the present study aims to answer the question: "Are yoga exercises effective in reducing menstrual pain and the lumbar lordosis angle in women with primary dysmenorrhea?"

3. Methods

The current research method is applied and semi-experimental, and Its design is pre-test-post-test in two experimental groups and two control groups.

3.1. The Method of Collecting Information and the Method of its Implementation

The statistical population of the present study was made up of women with primary dysmenorrhea with and without lumbar hyperlordosis from Islamic Azad University, Gohardasht Karaj Branch. At first, nearly 150 undergraduate students were randomly selected to identify primary dysmenorrhea through an interview form and to evaluate lumbar lordosis using the New York test. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria and obtaining the full consent of the volunteers, 60 qualified subjects in the age group of 20 - 35 years were selected using an available and targeted sampling method.

3.2. Instrument

After the initial evaluation and completion of the consent form and information collection form, all participants were screened using the New York Organizational Test method to identify and separate those suffering from lumbar lordosis. Pain intensity was measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and pain duration, as well as mood and emotional states, were assessed using the adjusted Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (MMDQ). Among these participants, those with hyperlordosis were re-evaluated using a flexible ruler to accurately measure the lumbar arch. At the end, 30 subjects with a curvature angle of more than 30 degrees were classified as having lumbar hyperlordosis and were randomly divided into two groups: An experimental group (n=15) and a control group (n = 15). Similarly, participants without hyperlordosis were divided into an experimental group (n = 15) and a control group (n = 15).

3.3. Procedure

The number of samples was determined using G*Power software (2.9.1.3) with an alpha level of 0.05, an effect size of 0.80, and power of 0.85. The software determined that 60 samples were required, which were then equally divided into 30 participants for the control group and 30 participants for the experimental group. All participants were aged 20 - 35 years, and their inclusion depended on the absence of hormonal drug use and structural damage in the pelvis. They reported moderate to severe primary dysmenorrhea during most menstrual periods, particularly in the last three months. A regular menstrual cycle and bleeding duration of 3 - 10 days were also inclusion criteria for the study.

Finally, after eight weeks of training in the experimental group and control group, the final test (post-test under pre-test conditions) was conducted. The data were recorded and analyzed.

3.4. Protocols Used in the Research

3.4.1. Yoga Group

For the experimental group, the yoga practice protocol was explained in detail and performed over eight weeks for 24 sessions (3 sessions per week) of 60 minutes each. Each session began with mindfulness and Nadi Shudana breathing exercises, followed by general warm-up exercises and six cycles of the Surya Namaskar asanas. The main asanas included Cobra Pose, Cat Pose, Shoulder Bridge Pose, Full Back Stretch Pose, Leg Lock Pose, Half Boat Pose, Shoulder Stand Pose, Fish Pose, Grasshopper Pose, Simple Bow Pose, and Camel Pose, each held for 10 breaths in 3 repetitions. Cooling down and general stretching exercises concluded the session, followed by Shavasana and one-hand exercises for 10 minutes.

3.5. Statistic

Data were analyzed after collection using statistical software (SPSS23). In the descriptive statistics section, the mean, standard deviation, and relevant tables were used. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to check the normal distribution of variables. In the second part, which is related to inferential statistics, the proposed hypotheses of the research were tested. Considering the relationship between the pre-test and post-test scores and the presence of an independent variable, a univariate covariance test was used to analyze group differences, and a paired t-test was employed to examine intra-group differences. For covariance analysis, the assumption of homogeneity of the regression slope was first tested, followed by Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances. The results showed that the regression slope assumption was met for all variables (pain = 0.123, distress = 0.993, lordosis angle = 0.050). Levene’s test also confirmed that variances were equal across all variables (pain = 0.847, distress = 0.130, lordosis angle = 0.339).

4. Results

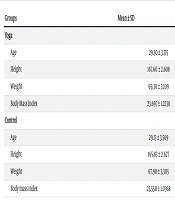

The subjects in the experimental group had a mean and standard deviation for age, height, weight, and Body Mass Index (BMI) of 29.30 ± 3.715, 167.60 ± 2.608, 69.30 ± 3.109, and 23.697 ± 1.2238, respectively. Similarly, the control group had values of 29.13 ± 3.569, 165.83 ± 2.627, 67.90 ± 3.305, and 23.550 ± 1.0368, respectively. The results of the demographic data analysis are shown in Table 1, and the results of data normalization from the Shapiro-Wilk test are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

| Groups | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Yoga | |

| Age | 29.30 ± 3.715 |

| Height | 167.60 ± 2.608 |

| Weight | 69.30 ± 3.109 |

| Body Mass Index | 23.697 ± 1.2238 |

| Control | |

| Age | 29.13 ± 3.569 |

| Height | 165.83 ± 2.627 |

| Weight | 67.90 ± 3.305 |

| Body mass index | 23.550 ± 1.0368 |

| The Dependent Variables | Yoga | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-test pain intensity | 6.33 ± 1.470 | 5.87 ± 1.925 |

| Post-test pain intensity | 3.67 ± 1.709 | 4.73 ± 1.741 |

| Pre-test distress | 68.27 ± 4.218 | 69.93 ± 5.369 |

| Post-test distress | 60.03 ± 4.567 | 69.10 ± 5.241 |

| Pre-test lordosis | 36.70 ± 5.066 | 32.77 ± 5.230 |

| Post-test lordosis | 30.70 ± 2.718 | 35.10 ± 5.461 |

| Dependent Variables | Shapiro-Wilk | |

|---|---|---|

| Degrees of Freedom | Significance Level | |

| Pre-test pain intensity | ||

| Yoga | 30 | 0.059 |

| Control | 30 | 0.270 |

| Post-test pain intensity | ||

| Yoga | 30 | 0.145 |

| Control | 30 | 0.249 |

| Pre-test distress | ||

| Yoga | 30 | 0.421 |

| Control | 30 | 0.455 |

| Post-test distress | ||

| Yoga | 30 | 0.981 |

| Control | 30 | 0.378 |

| Pre-test lordosis | ||

| Yoga | 30 | 0.201 |

| Control | 30 | 0.130 |

| Post-test lordosis | ||

| Yoga | 30 | 0.303 |

| Control | 30 | 0.270 |

According to the results of covariance analysis (Table 4), there is a significant difference in the post-test mean for pain intensity (P < 0.001), menstrual distress (P < 0.001), and lordosis angle (P < 0.001), indicating the positive effect of the yoga protocol on the improvement of women with primary dysmenorrhea.

| Variables | Effect Size | Significance Level | F | Average of Squares | Degrees of Freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of pain | 0.197 | 0.001 | 13.498 | 24.107 | 1 |

| Menstrual distress | 0.034 | 0.001 | 74.021 | 903.613 | 1 |

| Lordosis angle | 0.282 | 0.001 | 22.343 | 251.283 | 1 |

According to Table 5, after correlated t analysis, the results before and after the research for pain intensity (P < 0.001), menstrual distress (P < 0.001), and lordosis angle (P < 0.001) were significant in the intra-group comparison, demonstrating the positive impact of the yoga protocol. Yoga effectively improved the condition of women with primary dysmenorrhea.

| Variables | Effect Size | Significance Level | t | Difference of Means | Degrees of Freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of pain | 1.97 | 0.001 | 7.102 | 1.900 | 59 |

| Menstrual distress | 0.981 | 0.001 | 6.671 | 4.533 | 59 |

| Lordosis angle | 0.644 | 0.001 | 2.247 | 1.833 | 59 |

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of yoga exercises on menstrual pain and distress in female students aged 20 - 35 years with primary dysmenorrhea. The results of covariance analysis for the variables of pain intensity (P = 0.001, effect size = 0.197), menstrual distress (P = 0.001, effect size = 0.034), and the lordosis angle range (P = 0.001, effect size = 0.282) indicated a significant difference between the research groups.

The results of correlation t-tests for pre- and post-research values in pain (P = 0.001, effect size = 0.197), menstrual distress (P = 0.001, effect size = 0.981), and the lordosis angle range (P = 0.001, effect size = 0.644) showed significant differences between the groups. In terms of reducing pain intensity, menstrual distress, and the degree of the lordosis angle, the experimental group demonstrated a significant difference compared to the control group.

Overall, the effect of yoga exercises on the variables is considered excellent. Women with primary dysmenorrhea benefited significantly from yoga exercises in terms of pain intensity, menstrual distress, and lumbar lordosis angle. Primary dysmenorrhea causes numerous challenges in personal, social, and economic aspects of life, as well as in the physical and psychological health of women due to physical pain and hormonal changes (32). Many women with primary dysmenorrhea are unable to perform their usual work, leading to absenteeism from work and education. Some researchers estimate that 600 million working hours are lost annually due to dysmenorrhea (33, 34). Additionally, there is a higher likelihood of accidents and decreased work quality among individuals who continue working despite dysmenorrhea (35).

The results of the present study showed that yoga exercises have a significant effect on reducing pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. This finding aligns with studies conducted by other authors, which evaluated the overall effect of yoga on menstrual pain in primary dysmenorrhea, also confirmed that yoga is an effective intervention for reducing menstrual pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea, consistent with the present study's findings.

Previous studies have shown that yoga exercises reduce menstrual pain by stimulating uterine muscle contractions and suppressing pain through lowering prostaglandin production and myometrial ischemia via the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system (36-38). Additionally, yoga exercises regulate the nervous system, alleviate pain and fatigue, improve the functioning of internal glands and the digestive system, and enhance muscle function and flexibility (20, 25).

According to previous research and the obtained results, yoga can reduce menstrual pain and the social and psychological discomfort associated with this condition. As a potential treatment method, it can improve quality of life without side effects. One of the common causes of back pain in women, especially during menstruation, is increased curvature of the lumbar arch or hyperlordosis. Women with back pain often have poor trunk muscle endurance due to weaknesses in the abdominal muscles and thigh extensors, as well as anterior pelvic tilt. Trunk muscles play an important role in maintaining proper body control and spinal posture, making women with weak trunk muscle endurance more prone to back pain.

In the present study, the lumbar lordosis angle significantly decreased in the experimental group after the yoga intervention. In a comparative study of the effects of yoga exercises, TRX, and combined exercises on the lordosis angle in women with chronic back pain and increased lordosis, a significant difference in the lordosis angle before and after the interventions was found. Similarly, another study reported that 8 weeks of yoga exercises significantly improved spinal curvatures in women with mechanical back pain. Yoga exercises stretch shortened back muscles, psoas, and sphincter muscles while strengthening weakened abdominal and hamstring muscles, reducing anterior pelvic tilt and lordosis. Additionally, yoga postures alleviate pressure on nerves between vertebrae by improving physical fitness and training proper posture.

5.1. Conclusions

Menstruation is a completely natural phenomenon, and most women experience premenstrual syndrome and primary dysmenorrhea. Therefore, this condition does not necessitate a change in lifestyle. Women can still enjoy life, exercise, and have fun. Moreover, considering all the factors influencing this condition, performing yoga exercises a few times a week is likely to have beneficial effects. It is essential to take steps to ensure that all women are aware of the benefits of yoga and its effectiveness in managing menstrual pain.

Primary dysmenorrhea is a common problem among women and can interfere with family, work, and social activities. An educational program covering nutrition, stress management, and understanding the body's physiological conditions during menstruation could serve as a valuable and effective tool for improving women's health.

This topic is still relatively new and has not been extensively researched. There is a lack of comprehensive information in this area, necessitating further studies and exploration.