1. Background

There have been three major outbreaks of acute respiratory disease worldwide, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2013, and most recently, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (1, 2). Today, acute respiratory diseases are considered a crisis that threatens public health (3). Anxiety and worry caused by the severity of these diseases and the limitations of preventive measures create significant stress for everyone, especially healthcare workers (4).

Nurses are among the most vulnerable individuals on the front line of patient care (5). Factors such as long shifts, sleep disturbances, heavy workloads, and neglect of personal and family needs can lead to physical exhaustion and psychological stress among healthcare personnel (6). Burnout is a type of psychological crisis resulting from prolonged exposure to workplace stressors (7). Healthcare workers, particularly nurses who have direct patient contact, are more likely to experience occupational distress. Anxiety is a natural response in critical and life-threatening situations and can lead to irritability, insomnia, and reduced efficiency (8).

However, resilience serves as a protective adaptation strategy to cope with the negative effects of critical conditions. It is a positive process that helps individuals adjust to stressful situations, reducing the impact of sudden events and enhancing their ability to manage environmental challenges (9). Psychological flexibility is recognized as an essential coping mechanism in nursing, fostering hope, effective patient interactions, and increased self-efficacy (10).

Spiritual health is an abstract and subjective concept with no fixed definition but is recognized as a mental strength that enhances an individual’s ability to face work-related and life challenges. It has a positive effect on overall performance and well-being (11). Religious meditation is among the key factors that strengthen interactions between nurses and patients. The religious attitudes of nurses can contribute to disease prevention, improve health status, and help alleviate patients' pain, discomfort, and concerns (12). Some studies consider religious care an integral part of nursing care, aimed at meeting patients' spiritual needs (13).

Allport describes religious orientation as the practice of religious beliefs, which has both intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions. Intrinsic religious orientation is guided by an individual's core principles and is comprehensive, while extrinsic religious orientation is driven by personal needs such as social status and a sense of security (14). Some experts believe that patient satisfaction is significantly influenced by the physical and mental health of nurses (15). Studies have shown that nurses’ religious orientation has a considerable impact on their moral and behavioral attitudes, including stress management in the workplace during crises (16).

2. Objectives

Considering the importance of this topic and the lack of scientific studies in our region, we conducted a study to examine the relationship between resilience, burnout, and religious orientation among nurses in acute respiratory departments of Kermanshah hospitals, Iran.

3. Methods

The present study is a descriptive-analytical one. The statistical population consists of nurses working in acute respiratory departments of Kermanshah hospitals in Iran during 2020 - 2021. A total of 180 nurses were selected using an available sampling method.

To collect data, coordination was initially established with hospital officials, and nurses were then invited to complete the questionnaires. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical considerations, emphasizing the research aspect and ensuring the privacy of participants' data. A total of 180 questionnaires were distributed among the nurses, of which 20 were incompletely completed.

The questionnaires used in this study included a demographic information questionnaire, a religious orientation questionnaire, a resilience questionnaire, and a burnout questionnaire. The demographic information questionnaire collected personal details about the participants, including sex, educational level, and marital status.

3.1. Research Tools

3.1.1. Maslach Burnout Inventory Questionnaire

The Persian version of the 22-item Maslach Burnout Questionnaire was used to assess the frequency and severity of burnout in nurses. A Likert Scale was used to evaluate the frequency (0 = never, 6 = daily) and severity (0 = never, 7 = very severe) of burnout. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire have been confirmed by Iranian researchers.

3.1.2. Religious Orientation Questionnaire

The Persian version of the Allport Religious Orientation Scale (ROS) was used to assess the religious orientation of nurses. This questionnaire employs a 4-point Likert Scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (agree). Additionally, items 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10 are reverse-scored.

3.1.3. Resilience Questionnaire

The Persian version of the 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale was used to assess nurses’ resilience. This questionnaire employs a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from 0 (completely incorrect) to 4 (always correct). The subscales of this questionnaire include perception of individual competence, trust in personal instincts to tolerate negative emotions, positive acceptance of change and secure communication, control, and spiritual effects.

Questions 25, 24, 23, 17, 16, 12, 11, and 10 were used to assess the perception of individual competence subscale.

Questions 20, 19, 18, 15, 14, 7, and 6 examined the trust in personal instincts to tolerate negative emotions subscale.

Questions 8, 5, 4, 2, and 1 evaluated the positive acceptance of change and secure communication subscale.

Questions 22, 21, and 13 assessed the control subscale.

Questions 9 and 3 were assigned to examine the spiritual effects subscale.

4. Results

In this study, 160 nurses from hospitals in Kermanshah, Iran, participated during 2020–2021. The mean age was 31.60 ± 7.15 years, and the mean work experience was 7.27 ± 7.35 years. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 52 (32.50) |

| Female | 108 (67.50) |

| Level of education | |

| Associate degree | 4 (2.50) |

| Bachelor | 141 (88.12) |

| Masters | 15 (9.38) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 92 (57.50) |

| Married | 68 (45.50) |

Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

As shown in Table 1, 108 of the 180 participants (67.5%) were female. Four participants (2.5%) had an associate degree, 141 (88.1%) held a bachelor's degree, and 15 (9.4%) had a master's degree. Additionally, 92 participants (57.5%) were single. Table 2 presents the descriptive indicators for the variables of religious orientation, resilience (total score and subscales), and the severity and frequency of burnout.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Min - Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious orientation | 55.07 ± 8.15 | 35 - 76 | 0.33 | -0.19 |

| Resilience | ||||

| Individual competence | 22.79 ± 4.84 | 12 - 32 | -0.06 | -0.81 |

| Individual instincts | 17.44 ± 3.81 | 10 - 28 | 0.26 | -0.72 |

| Positive acceptance | 14.75 ± 2.47 | 10 - 20 | -0.05 | -0.75 |

| Control | 8.18 ± 1.91 | 3 - 12 | -0.16 | -0.35 |

| Spiritual influences | 5.18 ± 1.27 | 2 - 7 | -0.23 | -0.78 |

| Total | 68.34 ± 10.53 | 47 - 97 | 0.28 | -0.49 |

| Job burnout | ||||

| Severity | 68.86 ± 20.51 | 34 - 127 | 0.43 | -0.45 |

| Frequency | 67.31 ± 20.88 | 29 - 118 | 0.44 | -0.52 |

Descriptive Indicators for the Variables of Religious Orientation, Resilience (Total Score and Subscales) and Severity and Frequency of Burnout

As shown in Table 2, the mean and standard deviation were 55.07 ± 8.15 for religious orientation, 68.34 ± 10.53 for resilience, 22.79 ± 4.84 for perception of individual competence, 17.3 ± 4.81 for personal instincts to tolerate negative emotions, 14.75 ± 2.47 for positive acceptance of change in secure communication, 8.91 ± 1.91 for control, and 5.1 ± 2.27 for spiritual effects.

The mean and standard deviation were estimated to be 68.86 ± 20.51 for the severity of burnout and 67.31 ± 20.88 for the frequency of burnout. The lowest and highest scores for the research variables are reported in Table 2. Given that the skewness and kurtosis indices in our study range between +1 and -1, it can be inferred that the data follow a normal distribution, as also demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 3 presents the correlation between religious orientation and resilience (total score and subscales) as well as the severity and frequency of burnout.

Correlation Between Religious Orientation and Resilience (Total Score and Subscales) and Severity and Frequency of Burnout

As shown in Table 3, based on the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient, religious orientation had a significant positive relationship with resilience (r = 0.58), perception of individual competence (r = 0.33), personal instincts for tolerating negative emotions (r = 0.46), positive acceptance of change in secure communication (r = 0.38), control (r = 0.59), and spiritual effects (r = 0.56) (P < 0.001).

Moreover, religious orientation had a significant negative relationship with the severity of burnout (r = -0.47) and the frequency of burnout (r = -0.56) (P < 0.001).

Table 4 presents the results of the simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (enter method) used to predict religious orientation based on resilience, severity, and frequency of burnout.

| Variables | B | β | t | P-Value | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant (a) | 48.77 | - | 10.12 | 0.001 | - | - |

| Resilience | 0.29 | 0.38 | 5.71 | 0.001 | 0.77 | 1.30 |

| Severity of burnout | -0.08 | -0.21 | -3.25 | 0.001 | 0.78 | 1.28 |

| Frequency of burnout | -0.12 | -0.30 | -4.38 | 0.001 | 0.71 | 1.40 |

| Model summary | R | R2 | Adjusted R | F | P-Value | Durbin-Watson |

| 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 48.83 | 0.001 | 1.96 |

Results of Simultaneous Multivariate Regression Analysis (Enter) to Predict Religious Orientation Based on Resilience, Severity and Frequency of Burnout

As shown in Table 4, the values obtained for resilience, severity of burnout, and frequency of burnout exceed the acceptable threshold of 0.40. Additionally, the VIF statistics are close to the acceptable value of 1 for all variables, and the Durbin-Watson test result falls within the acceptable range (1.50 - 2.50).

Based on the results of the simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (enter method), resilience (β = 0.38), severity of burnout (β = -0.21), and frequency of burnout (β = -0.30) were significant predictors of religious orientation (P < 0.001). The findings of this study also indicated that the multiple correlation coefficient and the coefficient of determination between resilience, severity of burnout, frequency of burnout, and religious orientation were 0.70 and 0.48, respectively. Therefore, resilience, severity of burnout, and frequency of burnout accounted for 48% of the variance in religious orientation among nurses in Kermanshah hospitals.

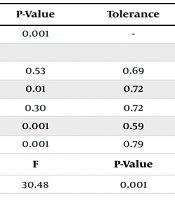

Table 5 presents the results of the simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (enter method) used to predict religious orientation based on resilience subscales.

| Variables | B | β | t | P-Value | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant (a) | 22.80 | - | 6.93 | 0.001 | - | - |

| Resilience subscales | ||||||

| Individual competence | -0.07 | -0.04 | -0.62 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 1.45 |

| Individual instincts | 0.38 | 0.18 | 2.62 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 1.39 |

| Positive acceptance | 0.23 | 0.07 | 1.03 | 0.30 | 0.72 | 1.38 |

| Control | 1.54 | 0.36 | 4.82 | 0.001 | 0.59 | 1.70 |

| Spiritual influences | 2.20 | 0.34 | 5.35 | 0.001 | 0.79 | 1.26 |

| Model summary | R | R2 | Adjusted R | F | P-Value | Durbin-Watson |

| 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 30.48 | 0.001 | 1.98 |

Results of Simultaneous Multivariate Regression Analysis (Enter) to Predict Religious Orientation Based on Resilience Subscales

As shown in Table 5, the tolerance values obtained for the resilience subscales exceed the acceptable threshold of 0.40. Additionally, the VIF statistics for all variables are close to the acceptable value of 1, and the Durbin-Watson test result falls within the acceptable range of 1.50 to 2.50.

Based on the results of the simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (enter method), some subscales of resilience, including personal instincts for tolerating negative emotions (β = 0.18), control (β = 0.36), and spiritual effects (β = 0.34), significantly predicted religious orientation (P < 0.01). However, the subscales of perception of personal competence (β = -0.04) and positive acceptance of change in secure communication (β = 0.07) were not significant predictors of religious orientation (P > 0.05).

The findings of this study also indicated that the multiple correlation coefficient and the coefficient of determination between resilience subscales and religious orientation were 0.70 and 0.50, respectively. Therefore, resilience subscales accounted for 50% of the variance in religious orientation among nurses in hospitals in Kermanshah.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between resilience and burnout with religious orientation in nurses working in acute respiratory departments of hospitals in Kermanshah. Among the 160 participants, 108 (67.5%) were female, 141 (88.1%) had a bachelor's degree, and 92 (57.5%) were single. To analyze the data, the Pearson correlation coefficient and simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (enter method) were used.

The results of the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a significant positive relationship between resilience, its subscales, and religious orientation, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.33 to 0.59 (P < 0.01) (Table 3). Additionally, based on the results of the simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (Enter method), the beta values for the total resilience score (β = 0.38), personal instincts for emotional tolerance (β = 0.18), control (β = 0.36), and spiritual effects (β = -0.34) predicted 50% of the variance in religious orientation (P < 0.001) (Table 5). These results are consistent with studies by Burnett and Helm, Dehghani, and Forouhari et al. (17-19).

This finding can be explained by the fact that individuals with higher resilience are more likely to seek meaning and purpose in life when facing difficult situations. Intrinsic religious orientation, which reflects true faith, increases people's tolerance and resilience in challenging circumstances, helping them navigate critical situations more effectively. Moreover, religious beliefs enhance individuals' adaptability. In general, resilience is defined as the capacity to cope with and overcome stressful events (20). However, resilience is not merely the ability to endure stress or life-threatening events; it also requires active and constructive engagement with the environment (21). Given that nursing is a profession that constantly involves stressful situations, nurses who are actively involved in patient care tend to have a deeper religious orientation, which helps them adapt to and manage critical situations.

On the other hand, the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient showed a significant negative relationship between the severity of burnout (r = -0.47), the frequency of burnout (r = -0.56), and religious orientation (P < 0.01) (Table 3). Furthermore, based on the results of the simultaneous multivariate regression analysis (Enter method), the beta values for the severity of burnout (β = -0.21) and the frequency of burnout (β = -0.30) predicted 48% of the variance in religious orientation (P < 0.001) (Table 4). These findings are consistent with studies by Babaei et al., Talebi et al., Polat et al., Najafi et al., and Harris and Tao (22-26).

This finding can also be explained by the fact that burnout is a psychological response to prolonged exposure to stressful events, leading to severe and chronic exhaustion (27). Burnout is also associated with negative changes in attitudes, moods, and behaviors in response to workplace pressures (28). Previous studies have demonstrated that religious involvement significantly improves mental health. The role of religious beliefs in mitigating psychological distress has been emphasized in many studies, showing an association between religious engagement and reduced psychological stress (29). Burnout affects all employees in a workplace, regardless of their position, and imposes substantial financial costs on both individuals and organizations (30). Thus, religion and spirituality can influence how individuals adapt to stressful life conditions by providing a framework for understanding the meaning and cause of negative events and offering a hopeful perspective on life. Religious beliefs also help individuals cope with workplace stress. Therefore, adherence to religious beliefs among nurses can delay occupational burnout.

5.1. Conclusions

Religious orientation is a predictor of both burnout and resilience in nurses and other healthcare personnel. Therefore, it is recommended that these individuals institutionalize spirituality and strengthen their religious attitudes in critical situations to reduce workplace stressors and enhance resilience.