1. Introduction

Adolescents’ problematic internet use (PIU) has garnered international attention (1). Recent research indicates that this phenomenon is associated with several detrimental effects. For instance, studies have shown that excessive internet use can lead to social relationship problems, increased anxiety and depression, and poorer academic performance (2). Moreover, a 2020 study found that reducing social media use to 30 minutes daily significantly enhances mental health and reduces anxiety (3). Following the COVID-19 pandemic, internet usage among Iranian adolescents has increased markedly (4). Recent studies report that the prevalence of PIU among Iranian adolescents has reached 10.3% post-pandemic. This alarming rise underscores the need for a comprehensive examination of preventive strategies. Excessive internet use can result in psychosocial issues, academic performance disruption, and a decline in physical health (5). Given that adolescents are at higher risk for developing PIU (6), it is crucial to develop effective preventive strategies tailored to Iranian culture. This systematic review aims to evaluate and synthesize existing evidence on PIU prevention methods for Iranian adolescents following the COVID-19 pandemic, providing practical guidance for policymakers, educators, and health professionals.

Examining PIU among adolescent students is of paramount importance. The ICD-11 approach appears to offer a realistic and reliable prevalence rate. In a study conducted using ICD-11 identification criteria, the prevalence rate for PIU was 2.98%, and for problematic gaming, it was 1.8%. Female gender predicted PIU, while male gender predicted problematic gaming (7). These concerning statistics highlight the urgent need for serious attention to this issue. Excessive internet use among adolescents is linked to numerous negative consequences, including academic decline, reduced interpersonal relationships, anxiety, depression, and decreased physical activity (8). Given that the internet has become an integral part of adolescents’ lives — playing a significant role in their academic, recreational, and social activities — it is vital to develop effective strategies tailored to Iranian culture for preventing and managing PIU in this age group. Doing so will not only improve adolescents’ mental health and academic performance but also help prevent more serious issues in the future.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic search using electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, covering the period from January 1, 2020, to January 1, 2025. The search focused on studies examining the prevalence of internet addiction among students aged 13-18 years in Iran following the coronavirus epidemic. Additionally, a manual search of references in relevant review articles was performed to ensure the inclusion of all related published articles. The search strategy was developed by combining Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms in both Persian and English from the PubMed database, as outlined below: (“Iran”[ti] AND “Internet addiction”[ti] OR “student*”[ti] OR “13 to 18 years of age”[ti] OR “Adolescent”[ti]) AND (COVID-19[mesh] OR COVID-19[ti] OR “covid 19”[ti] OR covid19[ti] OR Coronavirus[ti] OR SARS-CoV-2[ti] OR “SARS CoV 2”[ti] OR 2019-nCoV[ti] OR “2019 nCoV Disease”[ti] AND 2020/01/01:2025/01/01[dp]).

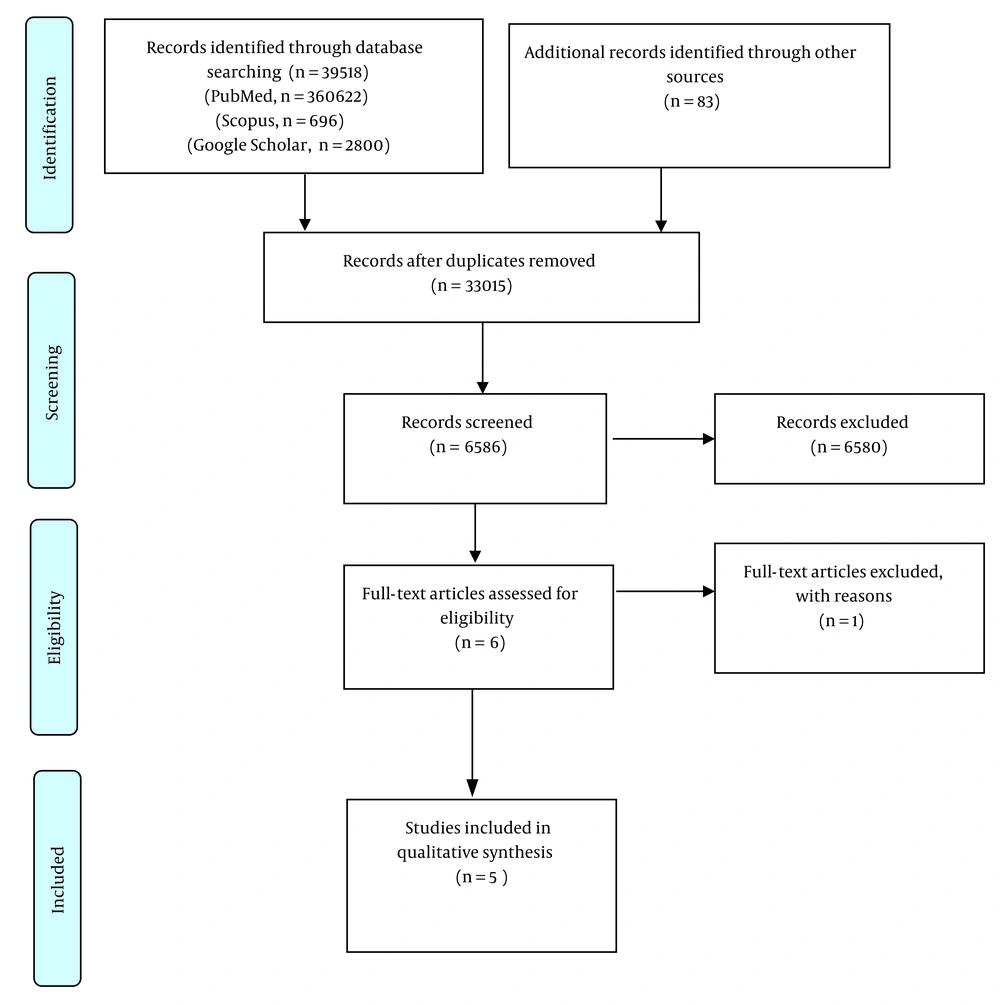

Our search yielded a number of potentially relevant articles from the aforementioned electronic databases. After removing duplicates and excluding studies based on title and abstract reviews, several studies were selected for full-text screening. Ultimately, five studies were included in the final analysis due to their relevance to the subject matter. The flow diagram of the screening process and study selection is presented in Figure 1.

Identification of studies through databases and registries based on (9) PRISMA follow diagram (2020)

For each electronic database, a specific search strategy was applied. The POLIS criteria were employed to develop observational studies related to the combination of evidence for study selection: (1) Patients: Adolescent students (13 - 18 years of age), (2) outcome: Internet addiction (IA), (3) location: Iran, (4) indicator: Prevalence of internet addiction, (5) study design: Cross-sectional studies.

2.2. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria for the Studies

The inclusion criteria encompassed any studies that examined the prevalence of internet addiction among Iranian adolescent students. No restrictions were applied based on participant age, gender, or search time frame for study inclusion. This review included cross-sectional studies. Case-report studies, studies lacking full text, and those focusing on other target groups such as Iranian university students were excluded from the review process.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Relevant studies were selected independently by two individuals at every stage of the study selection process, including screening, full-text review, and quality assessment. A pre-designed Excel form for data extraction and quality assessment of articles was provided to the two evaluators. For data extraction, variables included the publication year, name of the study’s first author, sample size, study design type, age range or mean age, target population, internet addiction prevalence rate, key findings, and quality assessment score.

2.4. Qualitative Assessment of Studies

To execute this section, two independent assessors employed a modified version of the quality assessment checklist for prevalence studies (adapted from Hoy et al.), specifically designed for cross-sectional prevalence studies (10). This tool comprises ten questions aimed at evaluating the risk of bias. For this study, the questions in this tool were modified to reflect the conditions of the included studies, and subsequently, a qualitative assessment of the articles was performed based on these modifications.

2.5. Data Synthesis

Data from studies examining the prevalence of internet addiction among adolescent students in Iran were analyzed using meta-analysis methods, employing the meta-prop command in STATA-17, and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To identify heterogeneity between studies, the I-squared test was used. The interpretation of I-squared values was as follows: I2 < 25%: No heterogeneity, I2 = 25 - 50%: Moderate heterogeneity, I2 > 50%: Substantial heterogeneity. To investigate the effects of potential factors contributing to the heterogeneity of internet addiction prevalence, Cochrane’s proposed approach of meta-analysis was used for sample size. The Egger test was employed to evaluate publication bias, with a P-value of less than 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Features of the Included Studies

Of the total number of relevant articles that were systematically reviewed, the characteristics of a total of 5 articles are reported in Table 1.

| Authors, Year | Men Age | Sample Size | Number of Male | Number of Female | Type of Addiction | Percent of Internet Addiction | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mokhtarinia et al., 2022 (11) | 14.49 | 589 | 385 | 385 | Smartphone | 53.3 | The increased reliance on smartphones by students during the Covid-19 pandemic has been linked primarily to eye strain and neck discomfort. It is crucial for parents to be aware of the potential long-term musculoskeletal and postural issues that may arise from prolonged smartphone use. They should closely monitor their children's smartphone habits, focusing on promoting proper posture and usage techniques that minimize eye strain and musculoskeletal stress, with particular attention to neck health. By doing so, parents can help mitigate the risk of future complications associated with excessive smartphone use. |

| Firoozi et al., 2022 (4) | 13 - 18 | 1385 | 859 | 859 | Internet addiction | 10.3 | Research indicates that the onset of Internet use and duration of online activity are key predictors of Internet addiction, while gender does not appear to be a determining factor. The study reveals a strong association between Internet addiction and leisure activities, particularly gaming, as well as inadequate parental guidance. Interestingly, educational use of the Internet was not found to contribute significantly to addiction. These findings highlight the importance of early intervention and parental involvement in shaping healthy Internet usage habits among young people, especially in non-academic contexts. |

| Salehi et al., 2022 (12) | 13 - 18 | 943 | 440 | 440 | Online addiction | 3.6 | The study findings revealed an inverse relationship between secure attachment styles and online addictions. Conversely, insecure attachment styles demonstrated a positive correlation with all three categories of online addiction examined. The research also indicated that young adults exhibited higher engagement in online activities, with online addictive behaviors showing an increase with age. Furthermore, a gender disparity was observed in online gaming addiction, with males displaying a higher prevalence compared to females. |

| Shokri et al., 2024 (13) | 13 - 19 | 407 | 222 | 222 | Internet addiction | 25 | The study revealed significant differences in lifestyle habits between students with and without internet addiction. Non-addicted students demonstrated markedly higher overall healthy lifestyle scores (P < 0.05). Notably, scores in spiritual growth, health responsibility, and nutrition were significantly better among non-addicted students compared to their addicted counterparts. |

| Akbari et al., 2023 (14) | 13 - 19 | 2390 | 1555 | 1555 | Problematic social media use with gaming disorder and gambling with social media | 18.5 | Adolescents experiencing concurrent problems with social media, gaming, and gambling demonstrate heightened psychological vulnerabilities, including increased internalizing symptoms, sensation-seeking behaviors, and social anxiety. |

3.2. Qualitative Assessment

All studies had a low risk of bias, and this is the greatest strength of our study, as articles with high assessment quality entered the work process (Table 2).

| Authors and Year | Was an Appropriate Case Definition Utilized in the Study? | Was the Study Instrument That Measured the Parameter of Internet Addiction? | Was the Same Method of Data Collection Employed for All Target Groups? | Was the Length of the Shortest Prevalence Period for the Parameter of Interest Appropriate? | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mokhtarinia et al., 2022 (11) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High quality of assessment |

| Firoozi et al., 2022 (4) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High quality of assessment |

| Salehi et al., 2022 (12) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High quality of assessment |

| Shokri et al., 2024 (13) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High quality of assessment |

| Akbari et al., 2023 (14) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High quality of assessment |

3.3. Prevalence of Internet Addiction Among Iranian Adolescent Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic

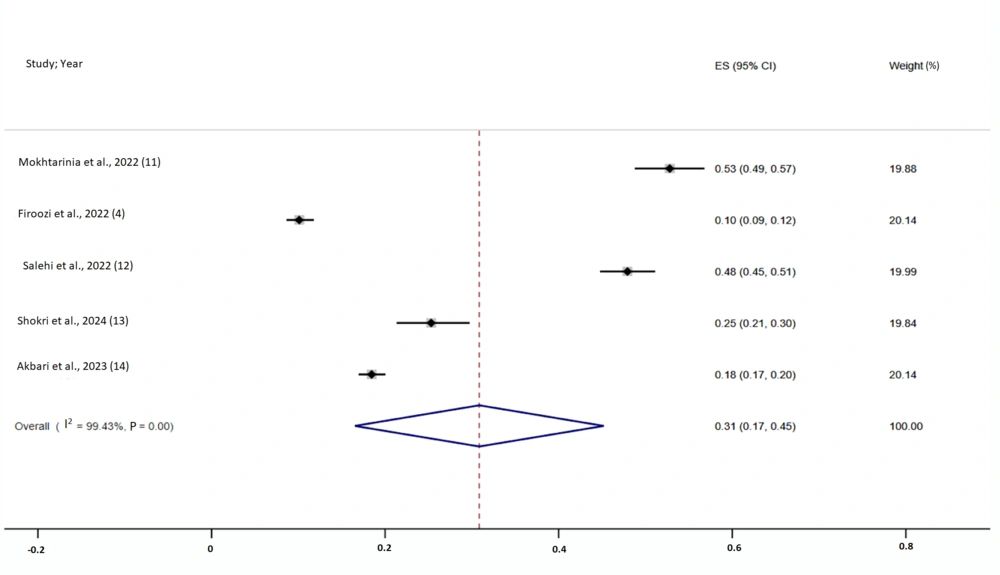

The primary outcome of interest for this study was to examine the prevalence of internet addiction among Iranian adolescent students. A total of five studies were included in the meta-analysis. Using a random-effects model, the prevalence of this behavior was calculated to be ES: 0.31 [95% CI = 0.17 - 0.45]. The heterogeneity (I2) was reported as I2 = 99.43%, which is statistically significant (P = 0.000), indicating high heterogeneity among these studies (Figure 2). The eligible studies were not suitable for subgroup analysis to reduce heterogeneity (Figure 2).

3.4. Meta-regression

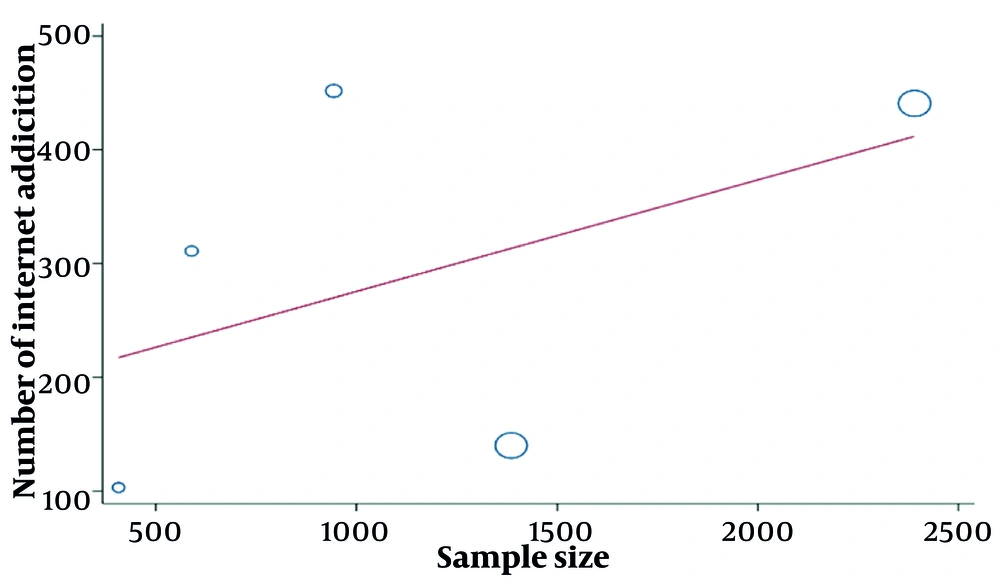

To examine the effects of potential factors influencing the heterogeneity in the prevalence of internet addiction, the Cochrane-recommended approach called meta-regression was used for sample size. Based on Figure 3, the results indicate that as the sample size increases in studies, the mean score of internet addiction also increases. However, this relationship is not statistically significant (P = 0.41).

3.5. Publication Bias

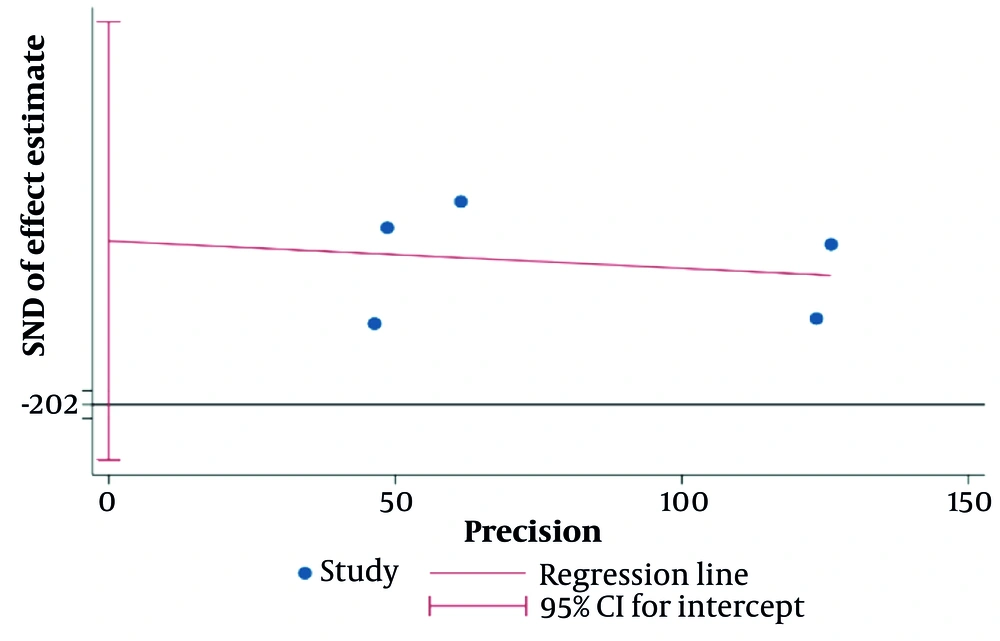

To assess publication bias and examine the small-study effect for this outcome, the Egger’s plot method was utilized. As shown in Figure 3, there is no regular distribution of studies, indicating the presence of publication bias. In the Egger’s plot, which examines the small-study effect, a P-value of 0.09 was reported. Although this value suggests a trend towards significance, it indicates the presence of publication bias (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The widespread use of the internet has resulted in both beneficial and detrimental effects on adolescents and young adults worldwide. The results of this meta-analysis indicate that the prevalence of PIU among Iranian adolescents after the COVID-19 pandemic is 31% (95% CI: 17% to 45%). This finding demonstrates a significant increase compared to pre-pandemic studies. In comparison with similar findings among Iranian university students in the post-COVID era, this result shows relatively similar outcomes. For example, a study conducted in 2022 reported the prevalence of internet addiction among Iranian university students to be 39.8% (15).

Moreover, compared to similar target groups of students before the COVID-19 pandemic, this result shows a substantial increase. In another study conducted in 2020, the prevalence of severe internet addiction among Iranian adolescents and young adults was reported to be only 2.4% (16). This significant increase could be attributed to various factors, including changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. During the period of quarantine and social restrictions, adolescents spent more time online, which may have led to an increase in PIU. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in 2022, which reported an increase in the prevalence of internet addiction among Tehran adolescents to 10.3% following the COVID-19 pandemic (4).

Understanding the factors contributing to the effects of increased internet use can aid in developing culturally appropriate strategies. Furthermore, the implications of these findings underscore the need for policymakers, educators, and healthcare providers to devise effective strategies to combat this emerging public health concern. The high heterogeneity (I2 = 99.43%) in this meta-analysis indicates significant differences between studies. These variations may stem from factors such as differences in study populations, diverse measurement tools, and temporal changes throughout the post-pandemic period. These findings highlight the importance of addressing PIU among Iranian adolescents.

Results from a similar study suggest that adolescents' internet behavior patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic have been diverse. Researchers found that various factors such as education level, academic score rankings, family functioning, and emotional and behavioral symptoms differed across different groups. These differences could explain the high heterogeneity in studies related to PIU among adolescents (17). Given the negative consequences of internet addiction on mental health, academic performance, and social relationships, there is a need for effective preventive and therapeutic interventions.

Ultimately, this study demonstrates that PIU among Iranian adolescents has increased following the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings highlight the necessity for greater attention to this issue and the design of appropriate intervention programs. Furthermore, conducting additional studies to examine the factors influencing this increase and strategies to address it appears essential.

4.1. Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows that the prevalence of PIU among Iranian adolescents has significantly increased after the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the negative impacts of this phenomenon on adolescents’ mental health, academic performance, and social relationships, there is an urgent need to design and implement effective preventive and therapeutic interventions. Moreover, further studies are necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to this increase and to find suitable strategies to address it.