1. Background

Motivational strategies for learning refer to the behaviors through which individuals deliberately regulate their level of motivation to engage in a task, complete it, or achieve a specific goal (1). Due to their critical role as an internal driving force in the learning process and academic achievement, motivational strategies have gained special importance, standing out among the other three learning strategies (2, 3). Numerous studies, both in Iran and internationally, have shown a significant relationship between motivational strategies — such as self-efficacy beliefs, motivational beliefs, task value beliefs, test anxiety, goal orientation, and achievement goals — and academic performance and progress (3-6). Furthermore, motivation plays a fundamental role in enhancing clinical competence and is essential for effective performance in real-life clinical settings. This is particularly important for nursing students who face multiple demands and stressors from patients and clinical environments (7). Several studies have identified low interest and motivation among nursing students as one of the main barriers to effective clinical education (8). On the other hand, high levels of motivation have been shown to support students in persisting in the nursing profession, pursuing higher education, achieving success, and advancing in their careers (9). Therefore, it is crucial for nursing educators to identify the motivational factors that contribute to students’ learning and use them to design educational programs that foster successful completion and positive learning outcomes (10). Given that some studies have confirmed a positive relationship between motivation and job satisfaction, academic progress, and self-regulated learning in nursing (11-14), a detailed investigation of the dimensions of motivational and learning strategies among nursing students — especially through an analytical approach — can help identify effective learning patterns and predictors of academic success. This is particularly relevant in the Iranian educational context, where comprehensive studies on these variables are still limited.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to explore both motivational and learning strategy dimensions, not only to describe the current status but also to clarify the relationships between these constructs through statistical analysis, thus providing a foundation for targeted educational interventions.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional research conducted to investigate the relationship between motivational strategies and learning strategies among undergraduate nursing students.

3.2. Participants and Setting

The study population consisted of all eighth-semester undergraduate nursing students at Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran, during the first and second semesters of the 2024 - 2025 academic year. Participants were selected from two nursing schools affiliated with the university: Khorramabad School of Nursing and Aligoudarz School of Nursing. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Being an eighth-semester undergraduate nursing student; and (2) not having any work experience as a licensed practical nurse. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Unwillingness to continue participation in the study; and (2) participation in a similar study in the past.

3.3. Sampling Method and Sample Size

A census and convenience sampling method was used. All eligible eighth-semester nursing students in the two schools were invited to participate. A total of 102 students completed the study instruments.

3.4. Data Collection Instruments

3.4.1. Demographic Questionnaire

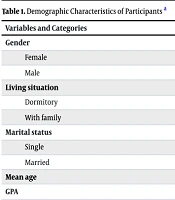

This form collected information on participants’ age, gender, marital status, and cumulative GPA from the first seven semesters.

3.4.2. Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire

Developed by Pintrich et al., the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) is a widely used self-report tool designed to measure students’ motivational beliefs and self-regulated learning strategies. The full version includes 81 items across 15 subscales, rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 ("not at all true of me") to 7 ("very true of me"). It consists of two major sections: (A) motivational strategies, including intrinsic/extrinsic goal orientation, task value, control of learning beliefs, self-efficacy, and test anxiety; (B) learning strategies, including rehearsal, elaboration, organization, critical thinking, metacognitive self-regulation, time and study environment management, effort regulation, peer learning, and help seeking (15). The internal consistency of the subscales in previous studies has been reported to be acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.65 to 0.84) (16, 17).

3.5. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires distributed to students in classroom settings during regular class hours. Participants were provided with explanations regarding the purpose of the study, assured of confidentiality and anonymity, and instructed on how to complete the questionnaires. Completing the MSLQ took approximately 20 - 30 minutes.

3.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 22). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage) were used to summarize demographic variables and subscale scores. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine relationships between motivational and learning strategies. In addition, multiple linear regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of learning strategies based on motivational components, and vice versa. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.LUMS.REC.1403.204). Participation in the study was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study.

4. Results

Table 1 represents descriptive and demographic statistics revealed that among the 102 participants, 52% were female and 48% were male. Most (90.2%) were single, and 52% lived in dormitories. The mean age was 24.05 ± 2.55 years, and the mean GPA was 16.75 ± 1.44. Descriptive analysis of the motivational strategies and learning strategies (Table 2) showed that among motivational components, self-efficacy for learning and performance had the highest mean score (42.08 ± 6.90), while extrinsic goal orientation had the lowest (16.36 ± 4.87). Regarding learning strategies, the highest average was observed in metacognitive self-regulation (52.69 ± 7.93), followed by time and study environment (36.16 ± 5.89).

| Variables | Range | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic goal orientation | 9 - 28 | 20.16 ± 4.03 |

| Extrinsic goal orientation | 4 - 28 | 16.36 ± 4.87 |

| Control of learning beliefs | 12 - 28 | 20.66 ± 3.09 |

| Self-efficacy for learning and performance | 24 - 56 | 42.08 ± 6.90 |

| Test anxiety | 7 - 32 | 18.47 ± 5.51 |

| Task value | 15 - 42 | 30.34 ± 5.24 |

| Motivation total score | 93 - 189 | 148.07 ± 19.13 |

| Rehearsal | 6 - 27 | 17.80 ± 4.14 |

| Elaboration | 12 - 40 | 28.11 ± 5.94 |

| Organization | 9 - 28 | 18.21 ± 4.72 |

| Critical thinking | 8 - 35 | 22.41 ± 4.76 |

| Metacognitive self-regulation | 35 - 75 | 52.69 ± 7.93 |

| Time and study environment | 19 - 47 | 36.16 ± 5.89 |

| Effort regulation | 8 - 25 | 16.46 ± 3.03 |

| Peer learning | 3 - 18 | 11.31± 3.18 |

| Help seeking | 6 - 57 | 17.36 ± 5.28 |

| Learning strategies total score | 115 - 310 | 202.71 ± 30.49 |

Descriptive Statistics for Motivational Strategies and Learning Strategies

Correlation analysis (Table 3) indicated significant positive relationships between the total motivation score and all learning strategy subscales except for help seeking. The highest correlation was found between self-efficacy and metacognitive self-regulation (r = 0.431, P < 0.01), and between task value and elaboration (r = 0.366, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the total motivation score was strongly associated with the total learning strategies score (r = 0.690, P < 0.01), supporting the close link between motivational and cognitive-regulatory processes.

| Variables | Learning Strategies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rehearsal | Elaboration | Organization | Critical Thinking | Metacognitive Self-regulation | Time and Study Environment | Effort Regulation | Peer Learning | Help Seeking | Learning Strategy Total | |

| Motivational Strategies | ||||||||||

| Intrinsic goal orientation | 0.244 a | 0.348 b | 0.278 b | 0.235 a | 0.363 b | 0.339 b | 0.291 b | 0.276 b | 0.165 | 0.452 b |

| Extrinsic goal orientation | 0.164 | 0.203 | 0.171 | 0.119 | 0.162 | 0.179 | 0.147 | 0.106 | 0.124 | 0.242 a |

| Control of learning beliefs | 0.189 | 0.289 b | 0.181 | 0.192 | 0.301 b | 0.256 a | 0.219 a | 0.142 | 0.178 | 0.366 b |

| Self-efficacy for learning and performance | 0.287 b | 0.410 b | 0.338 b | 0.273 b | 0.431 b | 0.371 b | 0.381 b | 0.279 b | 0.258 a | 0.568 b |

| Test anxiety | 0.075 | 0.145 | 0.079 | 0.050 | 0.084 | 0.058 | 0.052 | 0.009 | 0.041 | 0.119 |

| Task value | 0.219 a | 0.366 b | 0.253 a | 0.234 a | 0.336 b | 0.348 b | 0.288 b | 0.268 a | 0.180 | 0.480 b |

| Total motivation score | 0.353 b | 0.511 b | 0.389 b | 0.324 b | 0.507 b | 0.459 b | 0.412 b | 0.318 b | 0.272 b | 0.690 b |

Correlation Matrix Between Motivational and Learning Strategy Subscales

Multiple regression analysis (Table 4) examined whether motivational subscales could predict overall use of learning strategies. The model was statistically significant, F (6, 88) = 15.67, P < 0.001, explaining approximately 52% of the variance in learning strategy use (R2 = 0.517). Among the predictors, self-efficacy for learning and performance (β = 0.304, P = 0.006) and intrinsic goal orientation (β = 0.212, P = 0.043) emerged as significant predictors of learning strategies.

| Predictor | Standardized Coefficient (β) | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | - | 1.845 | 0.068 |

| Intrinsic goal orientation | 0.212 | 2.053 | 0.043 |

| Extrinsic goal orientation | 0.071 | 0.796 | 0.428 |

| Control of learning beliefs | 0.111 | 1.368 | 0.175 |

| Self-efficacy for learning and performance | 0.304 | 2.838 | 0.006 |

| Test anxiety | 0.076 | 0.921 | 0.359 |

| Task value | 0.218 | 1.900 | 0.061 |

Multiple regression analysis (Table 5) examined whether learning strategies subscales could predict overall use of motivational strategies. The model was statistically significant, F (9, 85) = 9.60, P < 0.001, explaining approximately 50% of the variance in motivational strategy use (R2 = 0.517). Among the predictors, time and study environment (β = 0.255, P = 0.006) emerged as a significant predictor of motivational strategies.

| Predictor | Standardized Coefficient (β) | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | - | 5.351 | 0.001 |

| Rehearsal | 0.059 | 0.540 | 0.591 |

| Elaboration | 0.137 | 0.870 | 0.387 |

| Organization | 0.165 | 1.337 | 0.185 |

| Critical thinking | 0.116 | 0.836 | 0.405 |

| Metacognitive self-regulation | 0.109 | 0.769 | 0.444 |

| Time and study environment | 0.225 | 2.266 | 0.026 |

| Effort regulation | 0.013 | 0.139 | 0.890 |

| Peer learning | -0.017 | -0.200 | 0.842 |

| Help seeking | 0.043 | 0.432 | 0.667 |

5. Discussion

This study explored the relationship between motivational strategies and learning strategies among undergraduate nursing students using the MSLQ framework. The results indicated a strong positive correlation between overall motivation and most dimensions of learning strategies. Notably, self-efficacy for learning and performance and intrinsic goal orientation were the most significant predictors of effective learning strategies such as metacognitive self-regulation and time management. These findings reinforce the importance of motivational beliefs in shaping strategic learning behavior. Recent studies have highlighted self-efficacy as a key driver of students’ engagement, persistence, and use of deep learning strategies (18). Specifically in nursing education, students with higher self-efficacy are more likely to regulate their cognition and behavior, set realistic goals, and manage their time effectively — skills essential for both academic and clinical success (18). The role of intrinsic goal orientation as a significant predictor aligns with the self-determination theory, which emphasizes that internally driven goals foster autonomy, competence, and deeper cognitive engagement (18). In contrast, extrinsic motivation showed limited predictive value in this study, supporting evidence that external rewards may not sustain long-term learning behaviors, especially in complex and emotionally demanding fields like nursing (19).

Although the observed correlations between task value and learning strategies such as elaboration and organization were statistically significant, task value did not emerge as a significant predictor in the regression model. This suggests its influence may be mediated by other motivational components such as self-efficacy. The predictive effect of metacognitive self-regulation and time and study environment management on motivational outcomes is also worth noting. These strategies not only facilitate academic performance but may also reinforce motivation by increasing students’ sense of control and achievement (20, 21). Such a reciprocal relationship implies that interventions aiming to strengthen one domain (e.g., time management) can positively influence the other (e.g., motivation).

Interestingly, help seeking did not correlate significantly with motivational strategies, a finding consistent with prior research that attributes this pattern to cultural or psychological barriers, such as fear of judgment or lack of trust in peers (22, 23). This may indicate the need for educational environments that foster safe, supportive peer interactions and destigmatize asking for help. Help-seeking behaviors among university students are shaped by a complex interplay of socio-cultural and psychological factors. Findings from studies indicate that fear of negative evaluation and perceived social stigma within academic environments constitute major barriers to seeking support (24, 25). A substantial number of students experiencing psychological distress refrain from seeking help due to beliefs in self-reliance, lack of trust in support systems, or concerns about compromising their academic credibility (26). These barriers are often more pronounced in collectivist cultures, where preserving family honor, maintaining social image, and ensuring group harmony are highly valued. In such context, students may avoid seeking support to protect their personal or familial reputation (27). This may help explain why certain subscales — such as test anxiety, peer learning, and help-seeking — did not yield significant predictive value in the regression models used in the present study. Rather than indicating a lack of conceptual relevance, these results may reflect avoidance behaviors or underreporting influenced by internalized stigma or academic pressures (28, 29). A more nuanced understanding of these patterns requires the adoption of qualitative or mixed-method research approaches. Techniques such as in-depth interviews or cultural discourse analysis can shed light on how students interpret and experience help-seeking within their specific cultural and social contexts (23, 30). Such approaches can help uncover hidden barriers and guide the development of culturally responsive interventions aimed at reducing stigma and enhancing access to both academic and emotional support.

From an educational standpoint, the findings of this study highlight the importance of fostering self-efficacy, task value perceptions, and self-regulated learning skills among students. Active learning strategies such as problem-based learning, simulation, and reflective practice have been shown to increase student engagement while promoting the development of sustained emotional, cognitive, and behavioral competencies (31-36). Instruction in self-regulated learning strategies has also been linked to enhanced academic attitudes, creativity, and cohesion in medical students (2). Furthermore, evidence suggests that self-efficacy and self-regulation are key predictors of academic buoyancy and resilience, enabling students to better navigate academic challenges (4). Strategic educational models, including those designed for virtual environments, have also demonstrated potential in fostering autonomy and motivation among learners (11). Overall, this study highlights the interconnectedness of motivational and cognitive-regulatory factors in learning, and underlines the importance of integrated educational strategies that address both domains simultaneously. Future research should explore these relationships longitudinally and assess the effectiveness of targeted interventions aimed at fostering motivation and self-regulated learning in clinical settings.

Despite its valuable contributions, this study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevents any inference of causality between motivation and learning strategies. Second, the use of self-reported questionnaires may introduce social desirability or recall bias. Third, the study was conducted at a single medical university, limiting the generalizability of the findings to broader nursing student populations. Additionally, the study did not include diagnostic tests to verify regression assumptions such as multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and normality of residuals, which may limit the interpretability of the regression outcomes. However, notable strengths include the use of a validated and comprehensive instrument (MSLQ), a relatively adequate sample size, and the application of both correlational and regression analyses to explore predictive relationships. The results have practical implications for nursing education, highlighting the need to foster self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, and metacognitive skills through structured, student-centered pedagogies. Future studies are recommended to employ longitudinal or interventional designs across diverse educational settings to examine causal relationships and evaluate the effectiveness of motivation-enhancing educational interventions on learning performance and clinical competence.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate a strong and statistically significant association between motivational and learning strategies among nursing students; however, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, no causal or reciprocal relationships can be confirmed. Self-efficacy and intrinsic goal orientation emerged as the most significant motivational predictors of effective learning behaviors. Likewise, metacognitive self-regulation and time management strategies were associated with increased motivation. These insights emphasize the importance of designing educational environments that simultaneously foster internal motivation and strategic learning. By integrating active, reflective, and student-centered learning approaches, nursing educators can support the development of autonomous and competent future nurses.