1. Context

The irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal (GI) tract disturbance affecting a considerable portion of the general population and is responsible for a large number of visits to physicians. The salient characteristic of the IBS is recurrent abdominal pain/discomfort with a concurrent disturbance in defecation (1). The IBS encompasses a wide array of physiological and psychological signs and symptoms which affect the cerebro-intestinal regulation, GI tract activity, and visceral perception (1, 2). The symptoms include altered bowel habits, without any organic pathology (3). Considerable evidence suggests that most patients with the IBS appear to have an enhanced perception of the overdistension of their rectum. This visceral hypersensitivity is presented by an increased intensity of sensations, intolerable intestinal pain, and/or propagated viscerosomatic referral in comparison to healthy subjects (4). Patients with the IBS demonstrate a number of other symptoms such as back pain, migraine headaches, epigastric pain, dyspareunia, and myalgia compatible with the possibility of central pain hypersensitivity mechanisms (5).

The IBS is a common gastrointestinal disease responsible for the patients’ referral to GI tract specialists (6). The first symptom-based criteria for the evaluation of the IBS were presented in 1978 by Manning et al. (7). The Manning criteria classified patients with abdominal pain on the basis of whether or not they suffered from organic disease (7). The Manning criteria were improved and published as the Rome I criteria in 1990. These new criteria were more detailed and contained more useful definitions of the syndrome (8). A decade later, the Rome I criteria were revised and upgraded into the Rome II criteria in order to suggest a relation between pain and stool consistency (8, 9). Ultimately, the Rome III criteria were presented in 2006 (10). The Rome III is a precise and more specified modification of the Rome II criteria. In the Rome III, pain must be confirmed at least 3 days a month in the previous 3 months (10). Hence, it is now possible to determine the exact prevalence and incidence of the IBS in accordance with the Rome criteria and forge compatibility in the studies conducted in this field.

The IBS exerts a negative influence on the lifestyle and daily activity of many of its sufferers (11-14), but it is still not clear whether it increases the patients’ mortality and morbidity. What is clear, however, is that this syndrome places a substantial financial burden on health care systems. The diagnosis of the IBS is made based on the criteria and exclusion of organic disease (10% - 15%) (11). The IBS was once thought to be common in females exacerbated by anxiety and depression. Recent statistical analyses have, nonetheless, suggested that the female gender is no longer a risk factor (15).

The prevalence of the IBS is on the increase in developed and particularly in developing countries. Pharmacological agents are used widely in all countries; some of these agents have proved their efficacy, while others have achieved partial clinical benefits (16). A review of psychological factors in patients who respond to specific psychological treatment plays a key role in their follow-up (17). To ensure simplicity, the present study does not delve into the details of statistical procedures.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Methodology

The databases drawn upon for data acquisition in the present study were Google Scholar, PubMed, and libraries and journals of the medical universities of the Islamic Republic of Iran as well as AJAUMS. The focus, however, was on the data published in the English language in the last 25 years, and in particular the past 10 years.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Manifestation of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

The cardinal manifestations of the IBS consist of continuous or relapsing abdominal pain and/or bloating, accompanied by change in defecation behavior, in the lack of constitutional disorders probable to assess for these symptoms. Subjects are observed for over 6 months to evaluate the presence of other diseases such as temporary infections or the GI tract malignancy, which are detected approximately within 6 months of symptom onset (18-20).

Based on the predominant defecation pattern, the IBS is sub-classified to diarrhea predominant (IBS-D) and constipation predominant (IBS-C). Additionally, a mixed bowel pattern (IBS-M) with both loose and hard stool is noted (18-20).

According to the Rome III criteria, the main manifestations of the IBS are abdominal discomfort, which is obviously related to intestinal dysfunction and is alleviated by defecation, and alteration in stool frequency or consistency. The most common clinical features are bloating, abnormal stool form and frequency, abdominal cramp, and mucus in feces. The patients tend to complain of the intervals of remission and the exacerbation of the symptoms (21, 22).

3.2. Abnormal Esophageal, Gastric, Small Intestinal, and Colonic Motility

Large and small intestine activity is widely studied in the IBS. There are some reports on the esophagus and stomach motility dysfunction. These malfunctions decrease the lower esophageal sphincter pressure and lead to abnormal contraction activity (23). Abnormal colon activity is known as the spastic and irritable colon (8). Twenty per cent of individuals alter their defecation behavior approximately once a year (20, 21), and some suffer from gastric emptying, especially of solid foods (24-26), which is particularly considerable in patients with constipation (27, 28). Furthermore, emotional status and anxiety attenuate the contractility of the stomach and lead to delayed emptying in comparison with healthy individuals (29). The peristaltic activity of the small intestine is faster in the IBS-D than in the other two types (30). Colonic distension (an intestino-intestinal inhibitory reflex that decreases duodenal motility) is impaired (31). Disturbed contractile activity is responsible for these clinical features (32, 33). In these patients, postprandial peristaltic hyperactivity and propagated motor response are more severe than those in healthy individuals (34-37).

3.3. Bloating

Abdominal pain and abnormal gas handling as a result of gas retention are very common. Abnormal contractile activity, accompanied by visceral hypersensitivity, is more important than abdominal distention due to intestinal gas (33). It has been reported that patients suffering from bloating have disturbed transit of extrinsic excess gas, which exacerbates their symptoms (25). Nutrition, physical activity, and body posture are factors that may alleviate this problem (38-42).

Ninety-six per cent of individuals suffer from abdominal gas retention, which is more frequent in women (43). However, this is not considered a differentiated character but an important feature of the syndrome (10). The patients tend to complain of a diurnal starting of abdominal gas excess, especially postprandial, which usually subsides or is relieved by the evening, which helps to determine the differential diagnosis of abdominal swelling such as an ovarian cyst or ascites (44, 45). Distension is only consistent with bloating in the IBS-C patients (60%) in comparison with the IBS-D patients (40%) (45).

3.4. Serotonin (5-HT) Role in Motility and Secretion Control

It is obvious that serotonin functions as a crucial neurotransmitter in the GI tract and participates in the pathophysiological status of the IBS. Serotonin modulates the GI autonomic nervous system, which influences the enhancement or inhibition of the GI secretion and motility. Abnormality in the serotonin signaling pathway gives rise to various annoying features of the disease (46). Serotonin excess is consistent with the IBS-D, and the inadequate secretion of serotonin is an important factor in the manifestation of the IBS-C. What confirms this hypothesis is that the postprandial blood levels of serotonin in individuals with the IBS-D are elevated. In addition, the platelet-depleted plasma 5-HT levels are elevated before and after meals. The tissue level of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA)/5-HT ratio is attenuated in individuals with the IBS-C, and there is a remarkable deficit in high plasma 5-HT fed levels in individuals with the IBS-C (46). Serotonin is gathered in the special cells (enterochromaffin cells) of the GI system and plays a crucial role in the contractile activity, visceral sensitivity, and gut secretion (47).

For the treatment of the symptoms of the IBS-D in females, the 5-HT3 antagonists are used widely. Ischemic colitis is an untoward effect and limits the prescription of these agents. Moreover, the 5-HT4 agonists have been approved for use in the management of the IBS-C in women as well as in the other constipation categories.

Serotonin is responsible for visceral hypersensitivity and contractile activity, and also participates in the modulation of the GI tract secretion and absorption (48, 49). It has been suggested that the 5-HT4 receptor agonists enhance the release of water and electrolytes in the small intestine (49).

3.5. Consensus-Based Pharmacological Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome

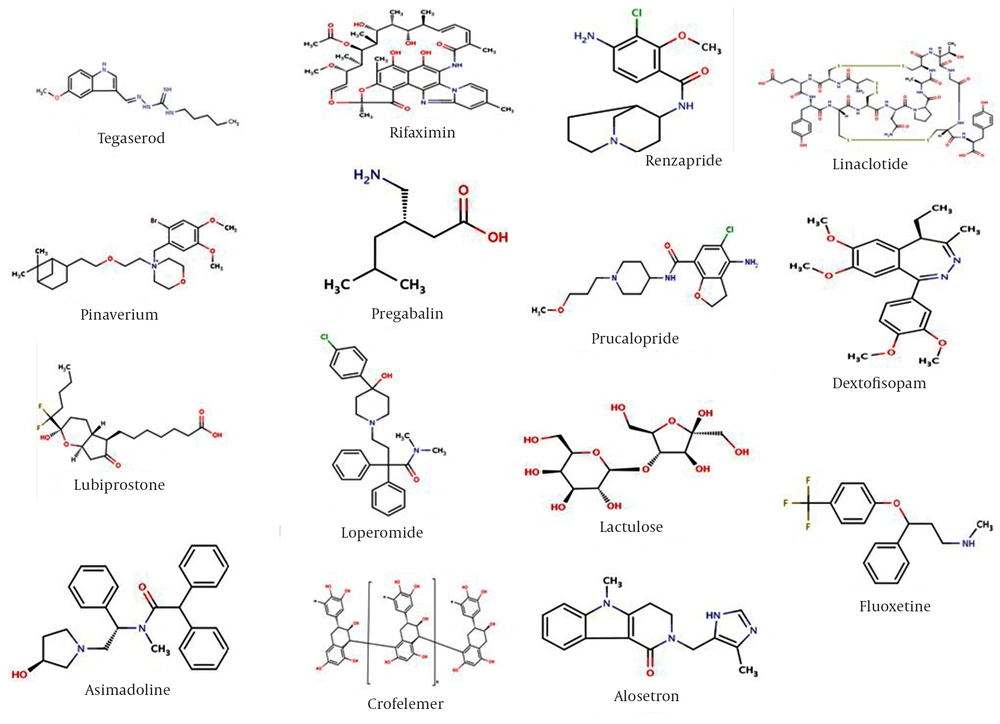

The pharmacological management of the IBS, albeit crucial, presents the prescriber with a major therapeutic dilemma. There have been no highly specific drugs particularly specialized for the management of this syndrome in recent years. Therapeutic protocols recommend that the patient’s predominant complaint such as pain, constipation, and diarrhea be addressed first and foremost. Multiple drugs are used for the management of this syndrome, albeit with low effect on subsiding pain and gas retention. Therapeutic goals emphasize on the control of the autonomic nervous system in the GI tract in order to improve bowel habits following the relaxation of the smooth muscle cells. This intervention attenuates the visceral noxious perception signaling. In the motility dysfunction of the GI tract, increasing or decreasing intestinal contractile activity is crucial (36, 50, 51). The chemical structures of some agents are depicted in Figure 1.

3.6. Drugs Acting on Central Nervous System

Some drugs function within the central nervous system (CNS). Dextofisopam is an R-enantiomer of tofisopam that binds to a specific site of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, inhibiting nerve signaling, and its advantages in the management of the IBS-D have been previously approved (52).

3.7. Kappa (κ)-Opioid Receptor Agonists

Visceral pain control in the GI system is a target for drug prescription. Peripheral κ-opioid receptor agonists block the signaling of the afferent pain perception from the intestines with no untoward effects such as dependency and constipation, which are observed in μ opioid agonists.

Kappa receptors are distributed in the stomach, large intestine, and cerebrum (53, 54). Asimadoline, a selective κ-opioid receptor agonist, possesses a low blood-brain barrier penetration potency and a negligible concentration level in the CNS. Its analgesic effect is modulated by the attenuation of nerve excitement (55, 56). Many human studies have shown that asimadoline decreases intestinal pain perception with no serious side effects (53-57). The potential and favorable role of the drug in the management of the IBS has led to further research (57), and statistical studies have shown defined and promising advantages in the control of visceral noxious perception and disturbed bowel habits in the D-IBS (58).

3.8. Antispasmodic Drugs

Anticholinergic agents inhibit the muscarinic receptors in the GI tract, decelerating the propagated contractile activities before and after meals, particularly in the IBS-D (36). The efficacy of antispasmodic agents has been evaluated by several meta-analyses (59-62).

Hyoscine, peppermint oil, and cimetropium are antispasmodic and relax the smooth muscle cells of the GI system (anticholinergic). Colonic spasm is a noxious symptom and a target of antispasmodic gents (63).

The nonspecific antagonists of the muscarinic receptor are dicyclomine and hyoscyamine (tertiary amines) as well as glycopyrrolate (quaternary ammonium compound) and methscopolamine. The low lipid solubility of the latter two compounds decreases the brain-blood barrier passage and lessens the CNS untoward effects such as drowsiness and nervousness (64).

Mebeverine is a musculotropic antispasmodic agent and a derivative of hydroxybenzamide. It has a direct effect on smooth muscle cells and blocks Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels (64). Mebeverine has no serious side effects and is used before meals. The efficacy of the drug in comparison with placebo has been confirmed (64).

3.9. 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists

The 5-HT3 receptor acts in the sensitization of the spinal sensory neurons, nausea stimulating vagal nerve, and peristaltic reflexes (49, 65). Alosetron is a potent 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and is more effective than antispasmodic agents (49). It inhibits basal secretion in the healthy jejunum (66) and is prescribed to improve the quality of life in the IBS-D females (67). Ischemic colitis and constipation are the untoward effects of alosetron, and they resulted in the withdrawal of this drug from the market in 2000. Alosetron was reintroduced in 2002 by the United States food and drug administration (FDA). This drug is recommended for female patients who suffer from the relapsing symptoms of the IBS-D (67), and a meta-analysis study has demonstrated its advantages in females with the IBS-D (68, 69). Alosetron is more effective than placebo in relieving visceral hypersensitivity and improving abnormal defecation behavior, stool consistency, and colonic spasm; nevertheless, the drug is absolutely contraindicated in constipation (68-70). Cilansetron is a newer similar agent for the management of the IBS-D and is prescribed for 3 to 6 months to treat noxious visceral perception and disturbed bowel habits in all patients (67, 71). The 5-HT4 receptor agonists modulate the visceral afferent function. The probable mechanism is the release of acetylcholine via the presynaptic 5-HT4 receptor on the cholinergic neurons. Tegaserod is a strong, bearable aminoguanidine indole selective partial agonist at the 5-HT4 receptor and has been approved for the management of the IBS-C (72). This agent has been evaluated in well-extended studies (16, 72) and has prokinetic effects in the small and large intestines (72-74). Tegaserod accelerates the upper and lower intestine contractile activity, induces prokinetic effects on the stomach, enhances bowel secretion, and improves constipation in women with the IBS-C (75). The advantages are those associated with defecation frequency (76). Some studies have shown that this drug enhances the quality of life (72, 74). The most common untoward effect of tegaserod (6 mg twice daily) is predictably diarrhea (77). Prucalopride is a newer 5-HT4 receptor agonist and has acceptable advantages in the management of the IBS-C. In Europe, this drug is recommended for the treatment of recurrent constipation in females (78).

3.10. 5-HT4 Receptor Agonists/5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists

Renzapride is a mixed serotonin receptor agonist/antagonist. It may be more effective than a single agent and is prescribed for the therapeutic management of the IBS-C. This drug facilitates motility thanks to its 5-HT4 receptor agonist mechanism, although its efficacy in the treatment of the IBS has yet to be documented (79).

3.11. Aminobutyric Acid Analogue

Pregabalin is a novel, second-generation γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) analog (α2δ ligand). It attenuates nerve action potential and blocks the release of excitatory neurotransmitters associated with depolarization-induced calcium influx (80, 81). The effectiveness of pregabalin in the management of pain with different origins has been demonstrated (80, 81).

3.12. Drugs Affecting Chloride Channels in Gastrointestinal Tract

Some agents act on the chloride channels by activating or inhibiting the efflux of chloride ions into the lumen of the GI tract. This phenomenon results in the maintenance of isoelectric equilibrium and isotonic environment by moving water in the GI tract lumen and sodium efflux subsequently. Accelerated intestinal secretion and excess fluid volume provide a new opportunity for the management of the patients suffering from prolonged constipation and the IBS-C (82, 83).

3.13. Activators

Lubiprostone activates the chloride ions channels. The FDA recommends this agent for the management of the IBS-C in females (82, 83). In addition, linaclotide is another activator of the chloride ions channels and functions as a guanylate cyclase-C agonist. This agent is an activator of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) chloride ion channels (84). There have been promising results in the use of lubiprostone for the management of the IBS-C (85-87).

3.14. Inhibitors

The K channels and the 3Na/2K pump develop an electrochemical driving force for the release ofchloride, which is followed by the secretion of sodium and water. The CFTR regulates the chloride ion channels. CFTR is an inhibitory enterocytes membrane component and blocks GI secretion.

Crofelemer interacts with the CFTR inhibitory function. It also possesses advantages in the management of the IBS-D and enhances secretion (88).

3.15. Antidepressants

The application of antidepressants in a considerable part of gastrointestinal disorders is accepted. The analgesic effect of some of these drugs is responsible for the relief of pain in these patients. The concurrent existence of anxiety and depression with the IBS is remarkable. Antidepressants are effective in relieving the visceral pain in the IBS through modulating the interactions between the central and enteric nervous systems (46, 84, 89-91).

Antidepressants are categorized as selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclics and related antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). The drugs include duloxetine, flupentixol, mirtazapine, reboxetine, tryptophan, and venlafaxine (84, 91, 92).

It should also be considered that, in addition to antidepressants therapy, psychological management has a crucial role in the IBS treatment.

3.16. Tricyclic Antidepressants

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and the IBS are the therapeutic targets of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). In a comprehensive study, one third of the subjects used an antidepressant, although the purpose of taking the drug was not obvious (92). TCAs are drugs with peripheral anticholinergic and non-SSRI effects. TCAs are prescribed in a various neurotic and visceral pain (89). The drugs may change pain perception (90), especially during severe stress (93), in addition to their antidepressant or antianxiety effects (90). Many studies have shown that low-dose TCAs effectively decrease symptoms. Amitriptyline, trimipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, and doxepin possess the pharmacological efficacy and potency to relieve pain. Mianserin is an SSRI and has similar effects. The initial analgesic effects of these drugs have led to the continuous use of these agents in individuals with the IBS-D (94). The untoward effects of TCAs are parasympatholytic symptoms such as constipation and blared vision, observed in 30% of subjects (90). These untoward effects often lead to drug discontinuation; it is, therefore, essential that prescribers counsel the patients about these side effects and explain the drug function and the need for its consumption for 1 to 4 weeks (94, 95). It is recommended that TCAs be used for 6 to 12 months and then tapered (93, 96).

3.17. Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibitors

The effect of SSRIs on the GI tract motility is more pronounced than that on decreasing visceral pain. Paroxetine accelerates gastric accommodation in healthy individuals and does not affect fasting gastric compliance (45, 97). SSRIs are widely used and have no serious untoward effects in the management of psychiatric disorders (98, 99). In four studies, the therapeutic standard dose regimen of SSRIs was applied in the IBS and improvement in lifestyle and global good advantages were observed. In addition, there was no considerable effect on noxious visceral perception (90, 97, 98). In another clinical study, 84% of the subjects who received SSRIs (vs. 37% on placebo) wanted to continue with the drug. SSRIs have convenient advantages in patients with somatization (100, 101).

3.18. Fiber and Laxatives

Constipation is a frequent complaint in the IBS-D. Many different drugs with naturally herbal-derived ingredients and/or chemical origins are applied to relieve this symptom. Fiber such as bran and methylcellulose helps form bulky feces and improve large intestinal motility.

The most important laxatives are divided into four groups: fecal softeners (e.g. liquid paraffin); stimulant laxatives (e.g. bisacodyl); osmotic laxatives (e.g. methylcellulose); and bulk-forming laxatives (e.g. lactulose). There is no sign of intestinal damage in the long-term prescription of laxatives, but the side effect of laxatives is hypokalemia. The untoward effects of stimulant laxatives are dependency and tachyphylaxis (102-104).

3.19. Antidiarrheal Drugs

The analogues of the opioid receptors in the GI tract such as diphenoxylate and loperamide inhibit intestinal motility and secretion. The anti-diarrheal effect of loperamide is higher than its anti-spasmodic effect (105, 106). Loperamide has negligible side effects. A combination of diphenoxylate and atropine (co-phenotrope) is available, but loperamide is preferred. Another agent is codeine phosphate, which is not convenient due to its risk of dependency (107). Both co-phenotrope and loperamide may be prescribed for the management of this syndrome (107, 108).

3.20. Antibiotics

Sometimes bacterial gastroenteritis results in the development of the IBS, as has been demonstrated in a large number of studies (109). The lactulose hydrogen breath test is useful and is positive in 70% of the IBS patients (110). In the absence of bacteria in the small intestine, lactulose fermentation does not occur and it reaches the large intestine without any chemical conversion (111). The presence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is suggestive for starting chemotherapy (109).

It is recommended to prescribe wide-spectrum antibiotics such as clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and doxycycline for 10 days. Thirty-three of these patients became asymptomatic (112). Rifaximin has also been demonstrated to be efficacious (113, 114).

3.21. Probiotics

Lilly and Stillwell were the first scientists to introduce probiotics in 1965. These agents modulate the intestinal flora (115). Of all FGIDs, the IBS has enjoyed most attention in terms of the possible role of the intestinal flora in the pathogenesis of probiotics in its therapy (116). Disequilibrium within the normal flora is suggested to play a part in the pathogenesis of the IBS (114).

Probiotics are microbial-derived factors that stimulate the growth of other organisms (117). Probiotics offer a less effective way for altering the bowel flora. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of probiotics have shown benefits with respect to some symptoms, especially bloating and flatulence.

Probiotics Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli species have been shown to improve the IBS symptoms (116). Bifidobacterium infantis (Bifidobacteria would displace the proteolytic bacteria, which cause diarrhea) has shown benefit by attenuating the hypersensitivity of the immune response (116, 118, 119).

4. Conclusions

The IBS is the most common gastrointestinal disorder seen in primary care. The pathophysiology of the IBS is complex and unclear. Both central and peripheral factors, including psychosocial factors, abnormal GI motility and secretion, and visceral hypersensitivity, are thought to contribute to the symptoms of the IBS.

The present review discussed some of the current and emerging therapies in the IBS based upon the evolving understanding of the pathophysiology of this disorder. The chief complaint of the IBS patients is abdominal pain. A percentage of these patients present with aggravated pain sensitivity to gut distention (visceral hypersensitivity).

Various pharmacological agents have been used in the management of the IBS, but with limited efficacy for the symptom-based approach. Consensus-based pharmacological therapy in the IBS advocates the use of traditional and/or novel drugs that have an equivalent effect on pain, flatulence, diarrhea, and constipation. The prescribed medications consist of TCAs, SSRIs, antispasmodics, centrally acting agents, κ-opioid receptor agonists, 5-HT3 receptor agonists and antagonists, aminobutyric acid analog, and agents acting on the chloride channels in the GI tract. In addition, antimotility drugs may subside diarrhea and laxatives may alleviate constipation. Finally, not only do probiotics offer considerable potential in the treatment of FGIDs, but also there is now new evidence to support their efficacy in the management of the IBS.