1. Background

Hematological malignancies (HM) constitute a group of pathologies having common anomalies of the bone marrow or the lymphatic system cell (1). In rich countries, hematological malignancies benefit from increased improvement in disease control and long-term remission through advances in diagnostic accuracy and new treatments (2, 3). In contrast, in developing countries, their care faces the problems of unavailability and expensiveness of many treatments as much as the problem of late diagnosis (4, 5). On the other hand, there is little data available on their treatment and their outcome due to the fact that medical databases are often incomplete or nonexistent, particularly in Africa (6, 7). In Madagascar, until 2011, there was only one cancer center, thus, only a few studies on the therapeutic aspects and outcome of all hematological malignancies was conducted. The Medical Oncology Unit of the Military Hospital of Antananarivo, Madagascar, managed cancer including hematological malignancies since December 2012. This pathology represents there the fourth most frequent cancer (8).

2. Objectives

We aimed to describe the therapeutic aspects and outcome of hematological malignancies managed in the oncology unit of the military hospitals of Antananarivo to improve their management in this center.

3. Methods

This was a longitudinal study (descriptive and analytic) carried out at the Medical Oncology Unit of the Military Hospital of Antananarivo from December 1, 2012 to August 31, 2015 (33 months). We included all patients followed, then excluded those without pathologic evidence, cases of monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), and cases of solid cancers. We retained all confirmed cases of hematological malignancies. We defined three subgroups: acute leukemia (AL) including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); lymphoproliferative syndrome (LPS) including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), multiple myeloma (MM), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL); and myeloproliferative syndrome (MPS) including chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and primitive myelofibrosis. Data were collected and treated on SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics and estimative survival time by the Kaplan-Meier with comparison of the “log rank test” levels of factors were used for statistical analysis. A significant difference was considered for a P value < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Brief Epidemiological Description

There were 57 confirmed cases of hematological malignancies among 732 (7.8%) patients followed in this center during the study. The mean age was 49 ± 15 years and the sex-ratio (male/female) was 1.71. The most represented HM were NHL (40.4%), MM (19.3%), and AML (12.3%) (Table 1).

| Diagnosis | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic Treatment Only | Chemotherapy | Total | |

| ALL | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| AML | 6 (86) | 1 (14) | 7 (100) |

| CLL | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| CML | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) |

| NHL | 6 (26) | 17 (74) | 23 (100) |

| HL | 2 (29) | 5 (71) | 7 (100) |

| Multiple myeloma | 5 (45) | 6 (55) | 11 (100) |

| Primitive myelofibrosis | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Total | 23 (40) | 34 (60) | 57 100) |

Distribution According to the Diagnosis and Treatment Received by Patients Followed for Hematological Malignancies at the Military Hospital of Antananarivo from December 2012 to Augusta

4.2. Therapeutic Aspects

The proportion of patients who received specific treatment varied according to the diagnosis. Overall, 60% of our patients received chemotherapy, which was our only specific treatment (Table 1). The most used chemotherapy protocols varied according to the diagnosis (Table 2).

| Diagnosis | Regimen 1 | Regimen 2 | Regimen 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHL | CHOP (9; 53) | R-CHOP (5; 29) | CHOP-Bléo (1; 6) |

| HL | ABVD (5; 100) | - | - |

| Multiple myeloma | MPT (4; 67) | MP (1; 16.5) | CPM-TD (1; 16.5) |

| CML | Hydroxyurée (4; 100) | - | - |

| Primitive myelofibrosis | Hydroxyuree (1; 100) | - | - |

| AML | Aracytine-adriblastine (1; 100) | - | - |

The Three Most Used Chemotherapy Protocols According to the Diagnosis for Hematological Malignancies at the Military Hospital of Antananarivo from December 2012 to August 2015a

4.3. Outcome

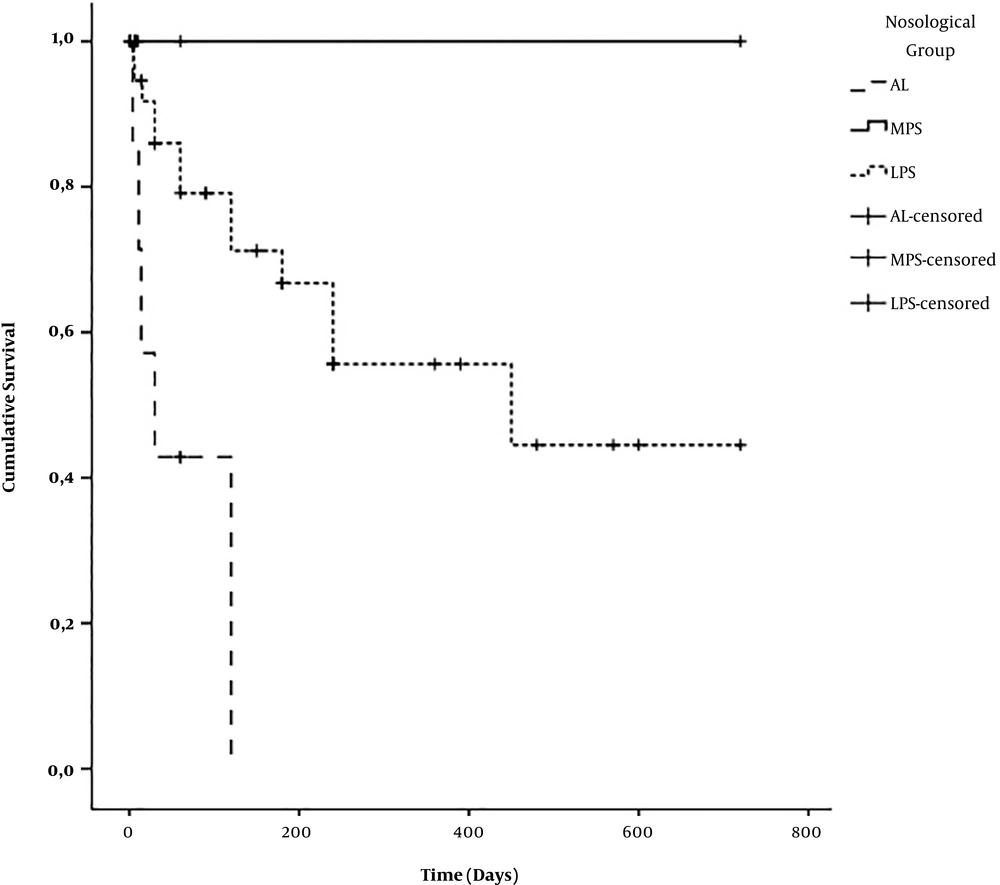

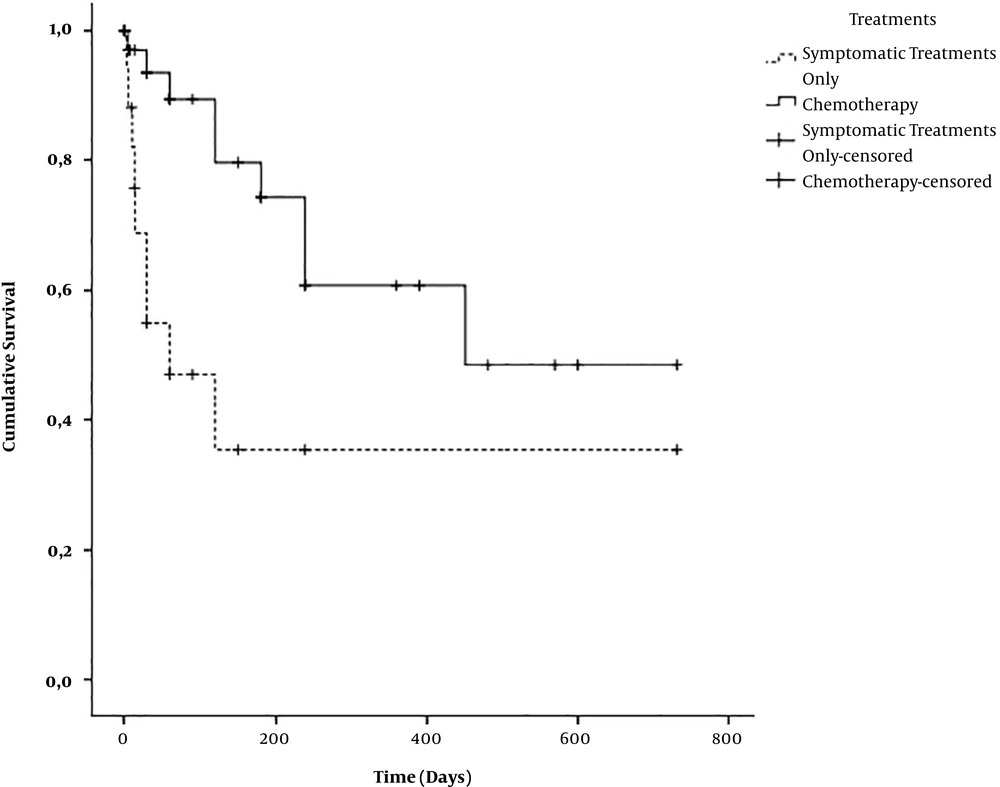

Mean survival time of all HM combined was 410 ± 61 days. According to the nosological subgroup, the mean survival time was 59 ± 22 days for AL, 721 ± 0 days for MPS, and 447 ± 70 days for LPS (P = 0.004) (Figure 1). The mean survival time of patients under chemotherapy was estimated at 491 ± 77 days while the overall survival time of patient under symptomatic treatment alone was estimated at 285 ± 99 days (P = 0.004) (Figure 2). No patient benefited from outside medical evacuation. After a median follow-up of 60 days with extremes of one and 780 days, 20 patients (35.1%) were alive, 20 (35.1%) had died, and 17 (29.8%) were lost to follow-up (Table 3).

| Diagnosis | State at Last Follow-Up | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased | Lost to Follow-Up | Alive | |

| ALL | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| AML | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) |

| CLL | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| CML | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) |

| NHL | 7 (30.4) | 8 (34.8) | 8 (34.8) |

| HL | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (57.2) |

| Multiple myeloma | 5 (45.5) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) |

| Primitive myelofibrosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Total | 20 (35.1) | 17 (29.8) | 20 (35.1) |

State at the Last Follow-Up According to the Diagnosis of the Patients Followed for Hematological Malignancies at the Military Hospital of Antananarivo from December 2012 to August 2015a

5. Discussion

A total of 60% of our patients received specific treatments. This is comparable to the results of Ouédraogo et al. in Burkina Faso and Thiam et al. in Senegal, for which 63.70% and 63.87%, respectively, of patients had received specific treatments. This concordance could be explained on one hand by the fact that lymphomas were the most represented HM in these studies as in our case, and on the other hand by the apparent similarity of our economic and social situation. Indeed, in many African countries, the management of HM often faces two major problems: The unavailability or inaccessibility of treatment molecules and the high rate of loss to follow-up, which is often caused by patient preference for traditional medicine (5, 9). The proportion of patients receiving specific treatments (60%) in our study is lower than that reported by Koulidiati in Burkina Faso, which was 94.35% (10). This difference could be explained by the fact that CMLs were the most frequent HM in their sample (24.30% vs. 10.53% in our study), whereas CML treatment is available and free in most developing countries including Madagascar (10, 11). Moreover, the proportion of patients benefiting from specific treatments varies, according to the center, even in the same country (9, 10).

Chemotherapy was the only specific treatment of HM in our study. This was also found in Ouédraogo et al. and Koulidiati et al.’s studies in Burkina Faso (9, 10). Our situation differs from that of Thiam et al. in 1996 in Senegal by the presence in his sample of two patients benefiting from surgery, one patient receiving radiotherapy, and four patients benefiting from external medical evacuation (5). The absence of radiotherapy in our study could be explained by the fact that radiotherapy was not functional in Madagascar during the study period (12). On one hand, the absence of external medical evacuation in our sample could be explained by our high rates of loss of follow-up and death. However, on the other hand, it can be assumed that, as in many African countries, the high cost of outside medical evacuations limits their access (5).

According to our study, the most used protocols for the treatment of NHL were CHOP (53%), R-CHOP (29%), and CHOP-Bleomycin (6%). Compared to the Koulidiati study in Burkina Faso, in 2015, for which the most used protocols were CHOP (47.83%), CHOP-Bleomycin (30%), and the combination cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone or COP (13.04%), our results differ by the more frequent use of rituximab (10). Rituximab is currently among the standard treatment of NHL in European countries (13). Thus, improving Malagasy patients’ access to innovative molecules would allow optimal treatment of NHL. Conversely, all our patients with HL benefited from the ABVD chemotherapy protocol. Our chemotherapy regimens differ from those found by Koulidiati et al. in Burkina Faso, from 2007 to 2012, for which the most prescribed protocols were: ABVD (42.86%), the alternation of the combination mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone (MOPP) with the ABVD (28.57%) and the MOPP (28.57) (10). The MOPP protocol is no longer included in recent recommendations, the front-line treatment standard of care for HL in European countries is currently the ABVD protocol (14). Thus, since all the molecules are available in Madagascar, our patients with HL have benefited from the optimal front-line treatment. In our case, the most commonly used chemotherapy regimens for MM patients were MPT (67%), CPM-TD (16.5%), and MP (16.5%). Our chemotherapy protocols are different from those of Koulidiati et al. in Burkina Faso by the more frequent use of thalidomide. Their most used protocols were the association of Melphalan, Prednisone or MP (52.63%), the association of vincristine, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, prednisone or VACP (39.47%), and the combination of vincristine, adriblastine, dexamethasone or VAD (7.90%) (10). Although we have thalidomide, unlike this study in Burkina Faso from 2004 to 2012, none of our patients were able to benefit from other new drugs of specific treatment of myeloma (10). In addition, none of our patients have benefited from hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (15). This situation can be explained by the absence of structures allowing HSCT in Madagascar. Improving drug access will help us in treating patients, according to international recommendations. Facilitating medical evacuation for patients who require it can be a non-permanent solution until the improvement of medical facilities. Finally, only one of our patients with AML was able to benefit from chemotherapy. The combination of aracytine with anthracycline was also the only protocol reported in the Koulidiati et al. study in Burkina Faso (10). However, due to the absence of HSCT in Madagascar, none of our patients with AML have benefited from the standard treatment to cure this disease (16).

Although CML is not one of our most common HM, it is worth mentioning that patients who have had CML were transferred to the Joseph Ravoahangy Andrianavalona Hospital, Antananarivo, a teaching hospital, to benefit from imatinib, which is free upon cytogenetic and/or biomolecular confirmation of the disease (11). Thus, facilitating access to imatinib in new cancer centers could be a major step in the management of CML in Madagascar.

On our 33-month study, the average survival of all our HMs was estimated at 410 ± 61 days. This varied according to the nosological groups of HM. The average survival of our AL was estimated at 59 ± 22 days, which was comparable to that found by Thiam et al. in Senegal, for which the mean survival of AL was 64.3 days (5). The average survival time of MPS, which was estimated at 721 ± 0 days, is far greater than that reported by Thiam et al. in Senegal, which was 185.5 days (5). This estimate is explained by the fact that CMLs, which accounted for 87.5% of our MPS, were transferred as soon as possible to the National Reference Center once the diagnosis was made. Given this bias, we cannot correctly estimate the actual survival time of our CMLs and SMPs. Moreover, the estimate of the survival time of our LPS (447 ± 70 days) is greater than the survival time found by Thiam et al. in Senegal (160 days) (5). This difference could be explained by our high rate of loss to follow-up, which could overestimate our survival, as it could underestimate it. It should be noted, however, that the more frequent use of rituximab in these patients may also explain a better prognosis.

At the end of our study, 35.1% of our combined HM patients were alive, 35.1% died, and 29.8% were lost due to a follow-up. Our proportion of deceased patients (35.1%) was comparable to that reported by Diallo et al. in Mali (33.33%) (17). Nevertheless, our proportion of deaths is higher than that found by Ouédraogo et al. and Koulidiati et al. in Burkina Faso, for which it was respectively 23.10% and 28.81%. Our higher proportion of deaths may be explained in part by the fact that our most represented HMs differ from those found by these authors, in particular their high proportion of CML (9, 10). We have to remember that the first-line reference treatment of CML is available and free in Madagascar as well as most developing countries via an international donation program, which has drastically improved their remission rate (10, 11). Moreover, our proportion of lost to follow-up is greater than that reported in other African studies. Mahboub et al. in Morocco, on thoracic HM and Koulidiati et al. in Burkina Faso, on all HM, found respectively 6.06 and 21.47% of lost to follow-up (10, 18). Thus, socio-economic and cultural studies should be done to determine the contributing factors of this loss to follow-up of Malagasy patients with HM. Similarly, the causes of HM mortality should also be studied later.

5.1. Conclusion

A total of 60% of HM managed at the Medical Oncology Unit of the Military Hospital of Antananarivo received specific treatment. These patients have significantly better survival than that on exclusive symptomatic treatment. Improving access to basic and life-saving drugs, and possibly the establishment of a hematopoietic stem cell transplant centre at the Military Hospital of Antananarivo, should improve the management and prognosis of patients suffering from HM, which are treated there. Even broadly consistent with African data, the high rate of death and loss to follow-up in this military medical oncology unit has to be explored by socio-economic and cultural studies.