1. Background

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) is defined as the presence of persistent proteinuria despite a four-week prednisolone or methylprednisolone therapy (1). This condition is still a threatening problem in pediatric nephrology, with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) as the most common histological finding. Meanwhile, FSGS is caused by podocyte damage and segmental sclerosis in multiple glomeruli and manifests clinically as proteinuria (2, 3). It decreases children’s quality of life, stunts their growth, and causes chronic kidney disease (CKD), and even end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Furthermore, FSGS is the leading cause of ESKD manifested as glomerular hyperfiltration and massive proteinuria, which progresses to the disruption of the filtration rate resulting in the disease mentioned (4).

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis patients are treated using a combination of steroids with calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) or alkylating agents (AA). The kidney disease initiatives for global outcomes (KDIGO) recommended the initial combination, and not the latter, because of its gonadal toxicity effect (4, 5). Moreover, the national insurance has a separate policy in verifying monoclonal antibody and CNIs (tacrolimus or cyclosporine A) for every patient. Hence, pediatric nephrologists still treat some SRNS children with an alkylating agent such as cyclophosphamide (CPA). From experience, the results of the latter therapy were as good as the first one as each disease activity was also identified. However, most studies demonstrated the superiority of CNIs to AAs in the management of SRNS. Lin et al. stated that tacrolimus (Tac) treatment had a high value of total remission and low value of proteinuria level when compared to those in cyclophosphamide (CPA) on six-month treatment of patients with membranous nephropathy (6). A meta-analysis conducted by Zhu et al. showed that CPA was comparable with Tac in inducing renal remission of membranous nephropathy patients within one year (7). Li et al. indicated a comparable remission rate with both Tac and CPA, while the long-term effects need further verification (8). Gulati et al., in their meta-analysis study, stated that the combination of Tac and prednisolone is superior to the CPA and prednisolone combination (9). Li et al. stated that cyclosporine A (CsA) is an effective and safe agent in the treatment of patients with SRNS. Yenigun et al. study demonstrated that CsA is not inferior to CPA in SRNS treatment (10).

Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is the circulating form of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored three-domain membrane protein expressed in various cells, including the immunologically active and endothelial types and podocytes (11-15). Furthermore, suPAR is a 20 - 55 kD protein, while circulating uPAR is a membrane-bound receptor for UPA and urokinase (3, 11-17). So far, only three known isoforms on humans and mice have been identified, including 1, 2, and 3. Also, suPAR is derived from immature myeloid cells, and its level increases in chronic infections such as HIV, septicemia, and malignancy. Similarly, uPAR is bound to the cell membrane through a moderate glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, which circulates in a soluble form (suPAR) and binds to the kidney podocyte's αvβ3 integrin when released. Subsequently, this affects the glomerulus leading to its malformation and structural abnormalities (3, 4, 18, 19). There are no studies on change in suPAR level with alkylating agent and CNIs in FSGS treatment. However, just recently, the usefulness of the soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor as a biomarker in clinically estimating and differentiating SRNS was corroborated (14, 15, 20-27). Some studies also reported that using suPAR level, it is possible to distinguish whether FSGS patients are responsive or resistant to therapy (23, 28). Wei et al. (26) stated that the serum concentrations of this receptor are significantly elevated in patients with FSGS compared to healthy subjects and in pre-transplant patients who later develop the recurrent form of this syndrome after transplantation (26, 29). Furthermore, some studies reported the usefulness of suPAR in identifying podocytopathy-related inflammation (30). In contrast, Peng et al. demonstrated that the receptor’s level helped to differentiate between SRNS and SSNS (23, 28). Therefore, changes in total suPAR are useful as biomarkers of glomerular disease activity (26). Furthermore, this receptor has also been found to not only affect FSGS and CKD, but when increased, it also affects the glomerular podocyte through the activation of integrin αvβ3. This subsequent injury causes further release of sclerosis and fibrosis-associated pro-inflammatory mediators (4). Also, the elevated suPAR levels were correlated with poor proteinuria outcomes in various populations (4, 26, 29, 31-39). In contrast, suPAR has been implicated in the pathogenesis of renal problems, specifically FSGS and diabetic kidney disease (DKD), through interference with podocyte migration and apoptosis (26, 29, 32, 40).

Although suPAR level is established as a FSGS biomarker, as a differentiator of SRNS and SSNS, as well as differentiating disease activity in SLE, there are no previous studies correlating suPAR level with protein loss through the glomerulus in other histological findings of SRNS. Also, no such comparison has been performed between this receptor and the change in urinary protein loss in two separate SRNS groups treated with CNIs and CPA.

2. Objectives

This study aims to specify the employability of suPAR as a noninvasive biomarker for monitoring therapy on SRNS children and compare the differences in clinical improvement in patients treated with AA and CNIs.

3. Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted between July 2019 and July 2020 at a single medical center known as Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia. The scientific and ethics committee of this hospital approved the protocol employed. Meanwhile, the parents and the subjects (when their age is > 12 or < 18) were informed of the potential risks associated with alkylating agents such as CPA and CNIs such as CsA or Tac. Also, written consent was obtained from subjects' parents and the subjects themselves if their age > 12 or < 18. Health insurance in Indonesia covered CPA fully, whereas the CNIs were only partially covered.

3.1. Patients

Seventy children with a working diagnosis of SRNS (age 1 - 18 years old) were enrolled in this study. Data were collected in July 2020 from medical records of the pediatric ward at Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia. All children diagnosed with SRNS from July 2019 - July 2020 were routinely evaluated for clinical signs and urinary protein every month. Also, the suPAR levels were measured thrice with an interval of three months. Furthermore, the syndrome’s inclusion criteria were based on the presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and swelling. Steroid resistance was defined as a positive urinary protein for more than four weeks of prednisone or methylprednisolone treatment. In addition, SRNS was defined as the persistence of proteinuria for more than four weeks after steroid therapy with a history of swelling and hypoalbuminemia (41, 42). The exclusion criteria included those with systemic diseases and severe infection before alkylating agent (CPA) or CNIs (Tac or CsA) therapy. Also, children with bladder dysfunction were excluded as they are at a high risk for hemorrhagic cystitis due to CPA (5, 43). Finally, individuals having blood dyscrasia, acute kidney injury (AKI), CKD, and severe infections were also excluded, as they are at a high risk for CNIs adverse effects (44, 45).

3.2. Indications for Therapy

Patients willingly decided to receive CNIs treatment (oral Tac or CsA combined with prednisolone given via the same route) or the AA (CPA) after explanation was made. Then, 40 mg/m2 alternative prednisolone dose was administered to the subjects in combination with oral Tac (Prograf, Astellas Pahrma, Hong Kong) of 0.05 mg/kg/day, which was divided into two doses over 12-hour intervals (28), or oral CsA (Sandimmun Neoral, Novartis, Indonesia) of 3 - 8 mg/kg BW/day (46), or intravenous CPA (Endoxan, Baxter, Indonesia) of 500 - 750 mg/m2/day intravenously for six months (6, 46).

3.3. Outcome Variables

The primary outcome measures were completed with partial remission, while the secondary outcomes included suPAR level, side effects, together with renal function during treatment and follow-up. The potential side effects were hemorrhagic cystitis, nocturia, enuresis, amenorrhea, delayed puberty, blood dyscrasia, AKI, and hypertension (8, 46-48).

3.4. Definitions

Complete remission (CR) is defined as the period when there is absence of swelling and proteinuria returns to the normal range (< 0.3 g/day). However, partial remission (PR) is when there is absence of swelling, but the non-nephrotic proteinuria (0.3 - 3.5 g/day) persists. The time required for PR was from the inception of prednisolone + Tac/CsA/CPA treatment to the first day that the partial remission was observed (49, 50).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to compare the suPAR level (ng/mL) in SRNS patients receiving the AA and CNIs. This test was also used to compare the urinary protein between both groups. Furthermore, the Mauchly's test was performed for the assumption of sphericity. Independent t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test were run to compare the subjects' age, gender, and blood pressure between the groups, respectively, and Mann-Whitney test to compare the urinary protein and baseline suPAR level between the AA and CNIs groups.

4. Results

As described in Table 1, the mean age was nearly similar between the two groups based on t-test (P = 0.140). Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome was more frequent in boys than girls (P = 0.020) according to the chi-square test, and the trend of higher blood pressure was indicated in the CNIs group. Also, proteinuria was demonstrated to be higher in those treated with the AA than in the CNIs group. However, suPAR levels before therapy were not different between the two groups.

Table 1 shows that the baseline serum suPAR level was not significantly different between the two groups. This was probably because the histopathological findings in both groups were nearly similar as most were FSGS (Table 2).

| Variables | Alkylating Agent (n = 35) | CNIs (n = 35) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 9.49 ± 3.66 | 8.17 ± 3.78 | 0.140 b |

| Gender | 0.020 c | ||

| Girls | 17 (49) | 8 (22) | |

| Boys | 18 (51) | 28 (78) | |

| Hypertension | 0.011 d | ||

| Stage 1 | 35 (100) | 29 (81) | |

| Stage 2 | 0 (0) | 7 (19) | |

| Urinary protein (g/day) | 2.5 (2.1, 2.8) | 2.2 (1.70, 5.18) | < 0.001 e |

| Baseline suPAR | 1.89 (1.02, 5.18) | 2.03 (1.66, 5.09) | 0.142 e |

Characteristic of SRNS Children Treated Using the Combination of Steroid with an Alkylating Agent or with CNIs a

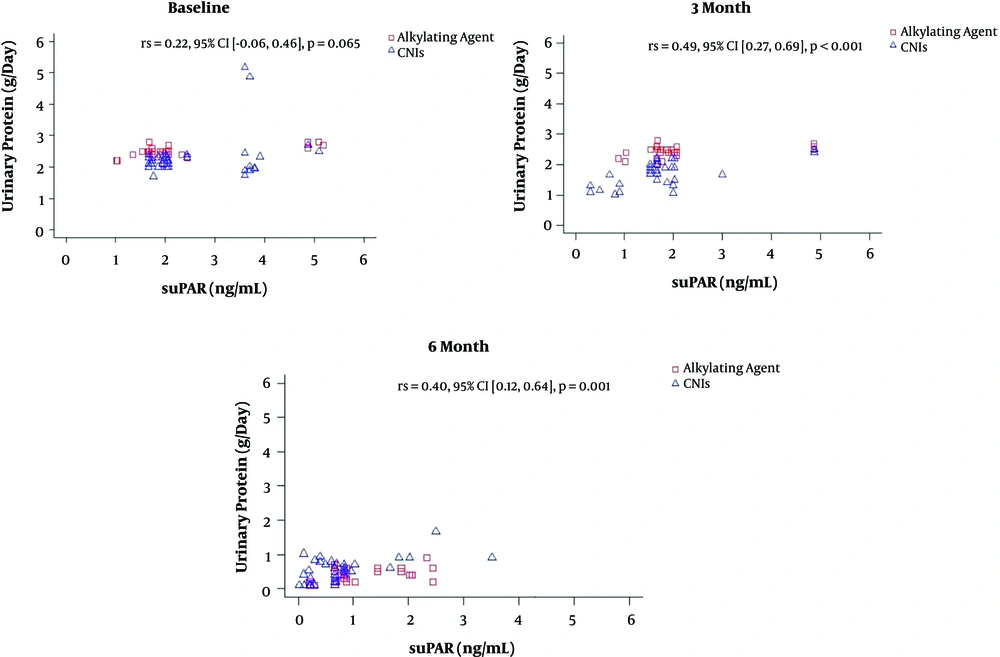

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome children have a tendency of experiencing improvement in proteinuria between the 3rd and 6th months of CPA therapy, meanwhile this was achieved earlier in the CNIs (CsA and Tac) group, that is, in the first three months (Figure 1).

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to compare the suPAR level (ng/mL) of SRNS patients that received the AA and CNIs (Table 3). A total of 70 children with SRNS were enrolled based on medical records, with 35 receiving either an AA or CNIs. The receptor's level was measured at baseline and three months and six months later. Also, the complete data was made available at all points in time for the whole patients. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met. There was a significant interaction between time and treatment (F(2,138) = 7.203, P = 0.001). Also, the post hoc comparison showed no difference in the suPAR level between both treatment groups at baseline (P = 0.501). Meanwhile, suPAR level was higher in SRNS patients that received alkylating agents than those given CNIs at the 3rd and 6th months; however, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.054 and P = 0.086, respectively; Table 3). Furthermore, none of the subjects experienced any adverse effects of CNIs or alkylating agents. Also, in the CNIs group, there were no reported cases of arrhythmia, cordis, AKI, electrolyte imbalance, gynecomastia, hypertrichosis, convulsions, or infections. Similarly, there were no signs of AKI, CKD, hemorrhagic cystitis, or gonadal hormone disorders in those that received alkylating agents. Partial remission was achieved faster in the CNIs group compared to the AA group. Meanwhile, the points at which CR was achieved were nearly similar (Figure 1).

| Time | Alkylating agent (n = 35) | CNIs (n = 35) | Mean difference (95% CI) | F(1,69) | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2.398 (0.202) | 2.590 (0.200) | -0.192 (-0.760, 0.375) | 0.457 | 0.501 |

| Third month | 2.300 (0.196) | 1.762 (0.193) | 0.538 (-0.010, 1.087) | 3.831 | 0.054 |

| Sixth month | 1.074 (0.120) | 0.780 (0.118) | 0.294 (-0.042, 0.630) | 3.039 | 0.086 |

Comparison of Estimated Marginal Means of suPAR Level (ng/mL) of Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome Patients That Received an Alkylating Agent and Those Given Calcineurin Inhibitors

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to compare the suPAR level (ng/mL) of SRNS patients that received the AA and CNIs (Table 3). A total of 70 children with SRNS were enrolled based on medical records, with 35 receiving either an AA or CNIs. The receptor's level was measured at baseline and three months and six months later. Also, the complete data was made available at all points in time for the whole patients. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met. There was a significant interaction between time and treatment (F(2,138) = 7.203, P = 0.001). Also, the post hoc comparison showed no difference in the suPAR level between both treatment groups at baseline (P = 0.501). Meanwhile, suPAR level was higher in SRNS patients that received alkylating agents than those given CNIs at the 3rd and 6th months; however, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.054 and P = 0.086, respectively; Table 3). Furthermore, none of the subjects experienced any adverse effects of CNIs or alkylating agents. Also, in the CNIs group, there were no reported cases of arrhythmia, cordis, AKI, electrolyte imbalance, gynecomastia, hypertrichosis, convulsions, or infections. Similarly, there were no signs of AKI, CKD, hemorrhagic cystitis, or gonadal hormone disorders in those that received alkylating agents. Partial remission was achieved faster in the CNIs group compared to the AA group. Meanwhile, the points at which CR was achieved were nearly similar (Figure 1).

Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was also used to compare the daily urinary protein level (mg/day) of SRNS patients in both groups. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was not met. There was a significant interaction between time and treatment (F(2,138) = 3.395, P < 0.001). Furthermore, Post hoc comparisons indicated no difference in daily urinary protein level between the two treatment groups at baseline (P = 0.177). Meanwhile, at the third month, the daily urinary protein levels were higher in SRNS patients that received an alkylating agent compared to the CNIs group (P < 0.001). Furthermore, at the sixth month, the daily urinary protein levels were lower in the SRNS patients that received the AA compared to those who received CNIs (P = 0.008) (Table 4).

| Time | Alkylating agent (n = 35) | CNIs (n = 35) | Mean difference (95% CI) | F(1,69) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2.489 (0.087) | 2.321 (0.086) | 0.167 (-0.077, 0.412) | 1.858 | 0.177 |

| Three months | 2.429 (0.052) | 1.743 (0.052) | 0.686 (0.539, 0.833) | 86.704 | < 0.001 |

| Six months | 0.349 (0.048) | 0.532 (0.047) | -0.184 (-0.317, -0.051) | 7.573 | 0.008 |

Comparison of Estimated Marginal Means of Daily Urinary Protein Level (mg/day) of SNRS Patients Who Received an Alkylating Agent and Those Who Received Calcineurin Inhibitors

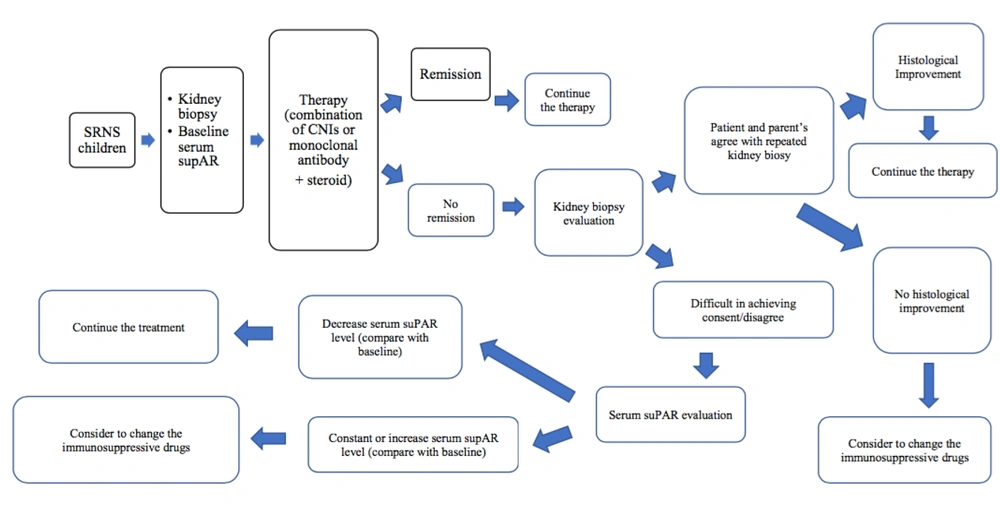

Figure 2 explains the alternative solution to SRNS therapy, notably for those with some difficulty in parent’s consent for repeated kidney biopsy.

5. Discussion

To the author's best knowledge, this study is the first to perform an outcome analysis of SRNS therapy with CNIs and the AA, using suPAR, as a candidate for a non-invasive modality. Our study showed that the treatment of SRNS with CNIs such as tacrolimus (Tac) or cyclosporine A (CsA) causes earlier remission than the AA (CPA). This lowers the tendency of proteinuria development into CKD in those treated with CNIs. However, the AA achieved remission results in the sixth month. The slow remission achievement incites the high risk for side effects with both steroids and CPA (51-55).

In addition, prolonged proteinuria increases the likelihood of developing glomerular sclerosis and even extensive fibrosis (41, 42, 56, 57). Extensive sclerosis or fibrosis stimulates the release of inflammatory mediators that potentially causes further podocyte apoptosis (56, 58). Furthermore, the persistence of this process will slightly loosen the slit diaphragm, thereby aggravating proteinuria leading to CKD deterioration (42). In this study, there was no significant difference in serum suPAR levels of subjects that were treated with CNIs for at least three months compared to those that received the AA treatment. Hence, this is an indication that apoptotic podocyte improved faster with CNIs than the alkylating agent. This finding is in contrast with Peng et al. (28) results, reporting that suPAR level was different between SRNS and SSNS groups. Furthermore, Peng and Mousa et al. also found that supAR was significantly higher in SRNS patients compared to the SSNS, SDNS, and normal population (23).

Soltysiak et al. discovered circulating suPAR as a biomarker of disease severity in children with proteinuric glomerulonephritis (59). Changli Wei et al. and Savin et al. stated that suPAR levels are specifically associated with primary FSGS, and chronic overexpression of suPAR leads to an FSGS-like nephropathy in mice, and treatment with mycophenolate mofetil was associated with a lower serum suPAR level (26, 60). Roca et al. found that in NS children due to FSGS, MCD, and membranous nephropathy significantly associated with age, GFR, and levels of several endothelial markers, including suPAR (61).

Fuentes reported elevated suPAR level in NPHS2 gene mutation (62), and Zhao et al. stated that suPAR levels were positively associated with IgA nephropathy, whereas plasma suPAR levels were not significantly different between FSGS and IgA nephropathy patients (63). Winnicki, in their cross-sectional study, found that higher suPAR level was predictive of FSGS progression to CKD (14). Wada et al (2016) conducted a comprehensive review regarding suPAR as a diagnostic and predictive biomarker of kidney diseases (25). Huang et al. and Stone et al. stated that urinary suPAR was specifically elevated in patients with primary FSGS (24, 64). Shuai et al. found suPAR as a potential biomarker for predicting primary and secondary FSGS (22), Enocsson et al. stated that suPAR levels predict damage accrual in patients with recent onset of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (65), and Zaitoon et al. found that suPAR may be one of the valuable indicators of disease activity in SLE (66).

This study’s findings were in contrast with previous results, as described above. However, these differences occurred because these studies compared SRNS with other conditions that were non-SRNS, whereas this study compared SRNS in two separate groups treated with CNIs and an AA (CPA). The baseline clinical conditions based on both physical examination and laboratory examination were the same in both groups. However, the situation was different after three months of therapy. Furthermore, the remission state as reflected by proteinuria after the third month was significantly different in the CNIs and AA (CPA) groups. Meanwhile, the clinically different condition was not followed by a significant difference in serum suPAR levels in the two groups. This suggests that serum suPAR level is not a suitable monitoring tool for SRNS, although it is suitable for SSNS.

Also, this study provides data for the developing countries, in that SRNS guidelines should follow KDIGO guidelines which no longer use CPA in SRNS therapy due to slow remission time. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children is still an enigma, notably in the low-socioeconomic countries. The national health insurance has minimal coverage for the affected children; therefore, to accommodate the financial ability and optimal treatment for SRNS, existing therapeutic and diagnostic modalities are expected to be accessible in addition to being scientifically proven to be useful and safe for patients. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that nephrotic syndrome occurs in boys more frequently than in girls, as most cases were probably secondary SRNS, which originated from MCD. Also, previous studies have proven that NS is more common in boys. Although most of them have good prognosis, a small proportion, however, are at risk of frequent relapses, steroid dependence, and secondary SRNS (67-69).

Podocyte injury in MCD and FSGS potentially progresses in extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, leading to further sclerotic and even fibrotic glomerulus (41, 57). Furthermore, patients treated with CNIs had a higher blood pressure trend which was possibly due to the greater level of suPAR in the group. Trivedi et al. reported five variants of FSGS, including not otherwise specified (NOS), tip, perihilar, cellular, and collapsing type (70). Also, higher suPAR release and other proinflammatory mediators associated with the collapsing glomerular manifested as hypertension and kidney deterioration tendency (70, 71).

According to Hayek et al. (15), suPAR is the circulating form of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol–anchored three-domain membrane protein that is expressed in a variety of cells, including immunologically active and endothelial types as well as podocytes (11, 26, 72). Furthermore, the urokinase receptor is known to be closely linked to inflammation, organ damage, and immune activation in various disease states (21). Therefore, both the circulating and membrane-bound forms are directly involved in regulating cell adhesion and migration through blood vessels (11). Meanwhile, the aforementioned blood pressure was influenced by heart contractility, frequency, intravascular volume, and vascular resistance. Hence, the inflammation on the endothelium notably in kidney vessels leads to increased blood pressure. Moreover, this syndrome is a common histopathological form of secondary SRNS, which was initially in the INS form.

Persistent proteinuria was due to podocyte effacement, injury, or collapse which led to glomerular sclerosis, fibrosis, and the progressive deterioration of the kidney (17, 57, 73, 74). Also, patients diagnosed with FSGS, MPGN, and Mes-GN have a greater tendency for developing hypertension, compared to MCD patients, except for when there is a state of steroid toxicity (68, 75-77). These results were in line with the KDIGO 2020 guidelines, which recommended that SRNS children should be treated with steroid and CNIs or monoclonal antibody. This is based on the fact that the earlier proteinuria is resolved, the lower the risk of getting CKD associated with the persistent form of this condition.

Finally, according to this study, the suPAR level was higher in SRNS patients that received the AA compared to those given CNIs (CsA and Tac) at the third and sixth months; however, this difference was not statistically significant, based on the two-way ANOVA. Meanwhile, the difference between the baseline and the third and sixth months was better in patients that received CNIs compared to the other group. This was evident in the differences between the marginal means of the third month and baseline suPAR level, which was greater in the CNIs group. Therefore, this study matched with the hypothesis stating that remission is achieved earlier in SRNS children treated with CNIs than in their counterpart. Moreover, an alternative solution to SRNS therapy was provided notably for cases that encountered some difficulties in getting parent’s consent for repeated kidney biopsy.

In sum, CNIs have a tendency to achieve faster remission than the alkylating agent. Nevertheless, suPAR is yet not employable as a noninvasive monitoring tool in SRNS treatment. Further multicenter-longitudinal studies with tighter and longer periods of measurement time as well as bigger sample sizes are warranted. Therefore, in some developing or low-socioeconomic countries, proteinuria is still used as a modality to monitor the outcomes of SRNS therapy.