1. Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common inherited respiratory disease with autosomal dominant inheritance, the incidence of which is increasing (1-3). Patients with CF and their families usually experience a reduced quality of life (4-8). This disease causes patients numerous social and economic problems (9-14). Therefore, CF treatment is of particular importance. The treatments currently used for patients with CF are generally preservative and do not lead to complete recovery (15-18). As a result, the provision of facilities to achieve better living conditions for patients with CF greatly matters (19, 20). For this purpose, the determination of the factors affecting the physical and mental health of patients is critical (21).

Smoking is one of the known factors that aggravate CF (22, 23). However, the effects of exposure to secondhand smoke (by parents) if not consumed by the individual him/herself are not very evident. Today, smoking is considered one of the most crucial causes of human mortality and, at the same time, the only preventable cause of mortality and disability in the world. Millions of lives are endangered annually due to smoking. Statistics show an increasing number of smokers, especially young women in developing countries (24, 25). Smoking is one of the common health problems that not only its use but also exposure to cigarette smoke causes numerous harms and consequences for humans; even exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of lung cancer or cardiovascular diseases (26). Cigarette smoke causes adverse changes in the body systems due to containing substances with oxidative stress properties, such as cotinine (27).

A 2003 study carried out by Gee et al. in the United Kingdom demonstrated that two items had a major impact on the quality of life in patients with CF, including higher disease severity and female gender, which were associated with reduced quality of life (28). A 2011 cross-sectional study performed by Cohen et al. in Brazil examined 75 patients with CF and showed that the factors, such as social issues and nutritional status, affect patients’ quality of life based on their age (29). In a 2013 study in Iran conducted by Kianifar et al. in Mashhad, it was reported that there is a significant difference between children with CF and the control group in emotional, social, and physical performance at school (6). A cross-sectional study conducted by Bodnar et al. in Hungary in 2014 on 59 patients with CF indicated that exposure to parental cigarette smoke and parental educational level had a significant effect on the children’s quality of life (30). Smoking, which is associated with numerous cardiovascular disorders and chronic diseases, is also common in Iran; therefore, it is highly important to recognize the complications and problems caused by smoking and take measures to reduce the consumption (31, 32).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the quality of life in patients with CF based on a history of smoking in parents.

3. Methods

This applied cross-sectional and analytical study was conducted on 100 patients with CF who were referred to Masih Daneshvari Hospital in Tehran, Iran, and were admitted from April 2019 to April 2021. The determination of sample size was based on the following formula with the consideration of alpha (first error of the study) of 0.05, d (accuracy) of 0.1, and P (frequency of quality of life) of 0.5.

After measuring height and weight, body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and the relationship between these factors (including a family history of smoking, pulmonary function tests, and BMI) with patients’ quality of life was assessed. The inclusion criteria were CF and age under 30 years. The exclusion criteria were age over 30 years and hospitalization in the intensive care unit. The data collection tool was a researcher-made 38-item questionnaire, which was provided to the research sample using the field method. Two methods of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and test-retest with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Pearson correlation coefficient were used to evaluate reliability. The content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity indices were determined to assess the amount of content validity. According to the table of laws, the CVR score for all items exceeded 0.62. All factors had a CVR of 0.90 or greater. The internal consistency of the items (Cronbach’s alpha = 91%) showed that all the items were highly correlated. Test-retest reliability using the ICC was 96%, and r equal to 0.87 at a P-value less than 0.005 was statistically significant.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 20). Mean ± standard deviation was recorded for quantitative variables. Frequency and percentage were recorded for qualitative variables. The independent t-test and Pearson correlation test were used in this study, with a significance level of 0.05. All patients entered this study with personal desire and were informed about the steps of the project. All patient information was kept confidential. Consent was obtained from the subjects before participating in the study.

4. Results

The data of 76 patients with CF referred to Masih Daneshvari Hospital in Tehran who were admitted from April 2019 to April 2021 were collected, and the quality of life was assessed based on a history of smoking in parents. In the investigation of a history of smoking in parents, 38 (50%) patients had parents who smoked, and 38 (50%) patients had parents who did not smoke. In patients with smoking parents, 31 (81.6%) fathers, 2 (5.2%) grandparents, and 5 (13.2%) others (close relatives) were smokers (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| 6 - 11 | 13 (17.1) |

| 12 - 14 | 4 (5.3) |

| > 14 | 59 (77.6) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 34 (44.7) |

| Male | 42 (55.3) |

| Smoking | |

| No | 38 (50) |

| Yes | 38 (50) |

| Relationship between consumer and patient | |

| Father | 31 (81.6) |

| Grandfather | 2 (5.2) |

| Others | 5 (13.2) |

Evaluation of Demographic Information of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis

The mean value of smoking history (duration of use) in patients’ parents was 15.01 ± 14.53 years, respectively. Furthermore, the mean value of smoking (number of cigarettes) in parents was 10.05 ± 8.67, respectively (Table 2).

| Variables | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of use (y) | 38 | 1 | 50 | 15.01 ± 14.53 |

| Numbers of smoked cigarettes | 38 | 1 | 40 | 10.05 ± 8.67 |

Evaluation of History and Rate of Smoking in Families of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis

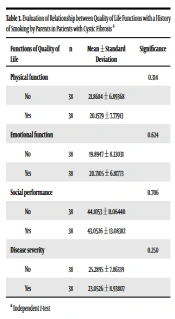

In this study, there was no statistically significant difference between physical, emotional, and social functions and disease severity with the history of smoking of patients’ parents (P > 0.05). The mean values of physical function in patients with a history of smoking and without a history of smoking were 20.15 ± 7.77 and 21.86 ± 6.89, respectively. The mean values of emotional function in patients with a history of smoking and without a history of smoking were 20.71 ± 6.81 and 19.89 ± 8.33, respectively. The mean value of social performance in patients with a history of smoking and without a history of smoking were 43.05 ± 13.08 and 44.10 ± 11.06, respectively. Finally, the mean values of disease severity in patients with a history of smoking and without a history of smoking were 23.05 ± 8.93 and 25.28 ± 7.86, respectively (Table 3).

| Functions of Quality of Life | n | Mean ± Standard Deviation | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 0.314 | ||

| No | 38 | 21.8684 ± 6.89368 | |

| Yes | 38 | 20.1579 ± 7.77913 | |

| Emotional function | 0.624 | ||

| No | 38 | 19.8947 ± 8.33031 | |

| Yes | 38 | 20.7105 ± 6.81773 | |

| Social performance | 0.706 | ||

| No | 38 | 44.1053 ± 11.06440 | |

| Yes | 38 | 43.0526 ± 13.08382 | |

| Disease severity | 0.250 | ||

| No | 38 | 25.2895 ± 7.86339 | |

| Yes | 38 | 23.0526 ± 8.93807 |

Evaluation of Relationship Between Quality of Life Functions with a History of Smoking by Parents in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis a

In this study, there was no significant relationship between patients’ quality of life with CF in physical, emotional, and social functions and disease severity with a family history of smoking (P > 0.05). The mean value of physical performance in patients whose fathers had a history of smoking was 20.38 ± 7.53. The minimum and maximum scores of physical performance in patients whose fathers had a history of smoking were 6 and 34, respectively. The mean value of physical performance in patients whose grandfathers had a history of smoking was 25 ± 9.89. The minimum and maximum scores of physical performance in patients whose grandfathers had a history of smoking were 18 and 32, respectively. The mean value of physical performance in patients with other family members with a history of smoking was 16.80 ± 9.09. The minimum and maximum scores of physical performance in patients with other family members with a history of smoking were 6 and 28, respectively.

The mean value of emotional performance in patients whose fathers had a history of smoking was 20.45 ± 7.00. The minimum and maximum scores of emotional performance in patients whose fathers had a history of smoking were 9 and 34, respectively. The mean value of emotional performance in patients whose grandfathers had a history of smoking was 22 ± 2.82. The minimum and maximum scores of emotional performance in patients whose grandfathers had a history of smoking were 20 and 24, respectively. The mean value of emotional performance in patients with other family members with a history of smoking was 21.80 ± 7.56. The minimum and maximum scores of emotional performance in patients with other family members with a history of smoking were 15 and 34, respectively.

The mean value of disease severity in patients whose fathers had a history of smoking was 23.09 ± 8.58. The minimum and maximum scores of disease severity in patients whose fathers had a history of smoking were 8 and 37, respectively. The mean value of disease severity in patients whose grandfathers had a history of smoking was 29 ± 5.65. The minimum and maximum scores of disease severity in patients whose grandfathers had a history of smoking were 25 and 33, respectively. The mean value of disease severity in patients with other family members with a history of smoking was 20.40 ± 12.30. The minimum and maximum scores of disease severity in patients with other family members with a history of smoking were 5 and 34, respectively (Table 4).

| Functions of Quality of Life | n | Mean ± Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 0.432 | ||||

| Father | 31 | 20.3871 ± 7.53957 | 6.00 | 34.00 | |

| Grandfather | 2 | 25.0000 ± 9.89949 | 18.00 | 32.00 | |

| Others | 5 | 16.8000 ± 9.09395 | 6.00 | 28.00 | |

| Emotional function | 0.891 | ||||

| Father | 31 | 20.4516 ± 7.00399 | 9.00 | 34.00 | |

| Grandfather | 2 | 22.0000 ± 2.82843 | 20.00 | 24.00 | |

| Others | 5 | 21.8000 ± 7.56307 | 15.00 | 34.00 | |

| Social performance | 0.336 | ||||

| Father | 31 | 42.2581 ± 13.18324 | 23.00 | 71.00 | |

| Grandfather | 2 | 56.5000 ± 7.77817 | 51.00 | 62.00 | |

| Others | 5 | 42.6000 ± 13.01153 | 27.00 | 59.00 | |

| Disease severity | 0.528 | ||||

| Father | 31 | 23.0968 ± 8.58819 | 8.00 | 37.00 | |

| Grandfather | 2 | 29.0000 ± 5.65685 | 25.00 | 33.00 | |

| Others | 5 | 20.4000 ± 12.30041 | 5.00 | 34.00 |

Evaluation of Relationship Between Quality of Life Functions with Family History of Smoking in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis a

There was no significant relationship between quality of life (i.e., physical, emotional, and social functions and disease severity) and the number of smoked cigarettes per day based on the Pearson correlation test (P > 0.05; Table 5).

| Quality of Life | Number of Cigarettes Smoked (Daily) by Smokers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Correlation | Significance | |

| Physical function | 38 | -0.082 | 0.625 |

| Emotional function | 38 | -0.173 | 0.297 |

| Social performance | 38 | -0.008 | 0.960 |

| Disease severity | 38 | -0.045 | 0.787 |

Evaluation of Relationship Between Quality of Life Functions and Number of Smoked Cigarettes (Daily) by Smokers in Family Members in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis a

There was no significant relationship between quality of life (physical, emotional, and social functions and disease severity) with the number of smoking years by family members of patients based on the Pearson correlation test (P > 0.05; Table 6).

| Quality of Life | Duration of Smoking (Year) in Samily Members | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Correlation | Significance | |

| Physical function | 38 | 0.63 | 0.706 |

| Emotional function | 38 | -0.216 | 0.192 |

| Social performance | 38 | 0.76 | 0.649 |

| Disease severity | 38 | 0.001 | 0.993 |

Evaluation of Relationship Between Quality of Life Functions and Duration of Smoking in Family Members of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis a

5. Discussion

Due to the pivotal role of health in quality of life, it is necessary to evaluate the quality of life in patients with CF regarding smoking history in parents to increase the quality of life. In the present study, patients in three age groups of 6 - 11, 12 - 14, and more than 14 years were included. Moreover, this study investigated the relationship between three physical, social, and emotional functions and disease severity with quality of life according to smoking history. In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in the quality of life of patients with CF and smoking in the parents of patients between the two groups of “smokers” and “nonsmokers” (P > 0.05). The obtained results in this regard are in line with the results of Bodnar et al.’s study (30). It should be noted that physical and social functions and disease severity in patients of the smoking family group were lower than in the nonsmoking family group. Another study has shown that in children’s emotional, social, and physical functions in school, a significant difference was reported between children with CF and a control group (6). In addition, in other studies, it was stated that children with CF exposed to tobacco smoke had a 4.7% lower ppFEV1 level than other children and altered patients’ metabolism (33-35).

Smoking is an exacerbation of the disease that leads to reduced quality of life in patients with CF (36-38). In this study, 50% of patients lived in the same house with at least one smoker. There was no significant relationship between patients’ quality of life with CF in physical, emotional, and social functions and disease severity with a family history of smoking (P > 0.05). However, despite the lack of a significant relationship, patients with CF with a smoking father had a lower quality of life, which is alarming. However, in Collaco et al. and Ortega-Garcia et al.’s study, it was stated that CF patients exposed to secondhand smoke were associated with a 10% reduction in lung function, which could reduce respiratory therapy in these patients, limit their respiratory capacity, and become problematic for patients’ growth pattern (39, 40).

In the present study, there was no significant relationship between patients’ quality of life in the group of smoking parents with the number of daily consumption of tobacco (cigarettes) by parents and the duration of smoking (year). Despite the aforementioned results, other studies have shown a significant relationship between tobacco smoke exposure and CF severity; accordingly, there were poorer spirometry results and a fivefold increase in the hospitalization rate of CF patients (36, 40).

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that smoking reduces the quality of life of patients with CF. Therefore, the need for the attention of parents and relatives of patients with CF to increase patients’ quality of life is seriously felt. However, in this study, no statistically significant relationship was observed between smoking in the relatives of patients with CF and reduced quality of life in these patients. One possible explanation for this result could be that obtaining a more accurate picture of the effect of cigarette smoke on the quality of life of patients with CF can be more realistic with a larger number of patients. Therefore, for further investigation, it is suggested to perform this study on a larger sample in different cities in patients with CF and compare the results.