1. Background

Since the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2019, a wide range of disease manifestations and complications has been observed. While respiratory symptoms are among the most prevalent presentations, other organs might be involved in different ways (1, 2). That’s why complications that are expected as a consequence of this infection are very different.

The World Health Organization (WHO) introduced SARS-CoV-2 as a major threat to mental health (3). People worldwide experienced a variety of psychological responses during the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. When people faced an unknown viral infection with a breakneck speed of spread, they normally responded to that with fear, anxiety, and even depression. These, alongside the economic burden induced by the pandemic, affect people in different aspects (4). Moreover, stay-at-home protocols of governments in infection prevention can significantly worsen the situation. Lack of physical contact with family and friends, especially when they are experiencing such tough moments, could worsen the mental problems (5, 6).

Eventually, WHO and other relevant organizations provided multiple guidelines for improving mental health and screening high-risk people such as children, older adults, and those with chronic mental illnesses, among others. Anxiety is one of the psychological problems that can be accompanied by fear, excessive concern, and mood instability. One of these high-risk populations comprises people who have underlying susceptibility to infections like primary immune deficiencies (PIDs) (7). In the first months of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, many of our PID patients stopped visiting hospitals. They preferred online visits, which caused multiple difficulties in managing their problems on time (8). So, we conducted this study to examine their psychological status over time.

2. Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from September 2020 to March 2021 among the pediatric population with PID and their family members. Psychological assessment in children was based on the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, and we also evaluated anxiety in their mothers using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Both of their Persian formats were validated by previous studies (9). The Zung Scale includes 20 multiple-choice questions (10). Each question is scored between 0 and 3, so the final score will range from 0 to 60. Scores above 26 are considered severe anxiety, while scores between 8 and 15 and between 16 and 25 are considered mild and moderate anxiety, respectively.

In the BAI, there are 21 multiple-choice questions describing common symptoms of this psychological problem, including mental, physical, and panic symptoms. Scoring is the same as the Zung Scale, but the final score will be 63. Each question is scored between 0 and 3. Scores above 26 are considered severe anxiety, while scores between 8 and 15 and between 16 and 25 are considered mild and moderate anxiety, respectively. After obtaining consent from the parents of the children, they were evaluated by a psychologist. Data were analyzed using SPSS 22, and the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were performed to check the normal distribution of the quantitative variables of age and the total score of the questionnaires. Ethical code: IR.MUMS.REC.1399.155.

3. Results

Among 30 patients with PID, with a mean age of 12.1 ± 1.4 years (range: 4 - 21 years), humoral immune deficiency was the most prevalent (30%). Other types of PIDs in our participants are listed in Table 1. Approximately eighteen participants (60%) had to regularly admit to the hospital and receive intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Others did not need IVIG at all. There was an equal frequency of compliance with quarantine. During the study period, 16 patients (53.3%) experienced at least one symptom attributed to infection, such as fever, chills, cough, fatigue, or sneezing. They underwent nasal PCR for SARS-CoV-2; however, only 5 patients had positive results.

| Variables | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 17/13 |

| Type of PID | |

| Humoral immune deficiency (CVID, Broton) | 9 (30) |

| CID | 2 (6.7) |

| Phagocytic disorder (neutropenia, CGD, LAD) | 5 (16.7) |

| MSMD | 2 (6.7) |

| Syndromic disease (hyper IgE, ataxia telangiectasia, wiskott aldrich) | 12 (40) |

Demographic Characteristics of Primary Immune Deficiency Patients Participating in Our Study a

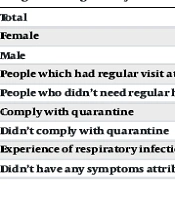

The mean score of the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale in primary immune deficient patients was 16.4 ± 4.2 (range: 9 - 26). There wasn't any statistically significant relationship between the total Zung score and age (P-value = 0.876) or sex (P-value = 0.98). However, there was a significant relationship between anxiety and regular hospitalization for IVIG administration (P-value = 0.001). In addition, those PID patients who didn’t comply with quarantine had significantly more anxiety (P-value = 0.02). More details are in Table 2.

| Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale | Mean ± Standard Deviation | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 16.4 ± 4.2 | |

| Female | 16.38 ± 3.7 | 0.98 |

| Male | 16.41 ± 4.8 | |

| People which had regular visit at hospital for IVIG infusion | 19.50 ± 4.18 | 0.001 |

| People who didn’t need regular hospitalization for IVIG | 14.33 ± 2.97 | |

| Comply with quarantine | 14.94 ± 2.55 | 0.02 |

| Didn’t comply with quarantine | 18.57 ± 5.46 | |

| Experience of respiratory infection manifestation during study | 16.1 ± 3.72 | 0.59 |

| Didn’t have any symptoms attributing to the respiratory infection | 16.85 ± 4.97 |

Mean Scores of the Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale

The mean score of the BAI in mothers of PID patients was 8.56 ± 7.45 (range: 0 - 22). Because the distribution of this score was abnormal, we analyzed it using Spearman’s statistical analysis. There was a significant relationship between the age of children and the anxiety of their mothers. As a result, mothers of younger PID patients had more anxiety (P-value = 0.019). In addition, there was more anxiety in those mothers whose children experienced suspected COVID-19 manifestations and those whose families didn’t comply with quarantine. However, regular hospitalization for IVIG did not cause a higher anxiety score in mothers. More details are in Table 3.

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | Mean ± Standard Deviation | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 8.56 ± 7.45 | |

| People which had regular visit at hospital for IVIG infusion | 14.81 ± 1.2 | 0.59 |

| People who didn’t need regular hospitalization for IVIG | 16.54 ± 2 | |

| Comply with quarantine | 11.56 ± 1.5 | 0.03 |

| Didn’t comply with quarantine | 21.42 ± 3.2 | |

| Experience of respiratory infection manifestation during study | 18.56 ± 2.5 | 0.04 |

| Didn’t have any symptoms attributing to the respiratory infection | 12.2 ± 1.3 |

Beck Anxiety Inventory in Mothers of PID Patients

4. Discussion

After the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, strict regulations were put in place to enforce staying at home, which restricted social interactions and led to major concerns about this mysterious contagious infection. There wasn’t any effective approved preventive or treatment strategy, so mental health was treated as a major concern, especially in immunocompromised patients (3, 5, 6). We conducted this study in the first year of the COVID-19 outbreak, aiming to investigate anxiety in children with inborn errors of immunity and their mothers. According to our data, there was mild to moderate anxiety in PID patients aged 12.1 ± 1.46 years during the first year of the COVID-19 outbreak. Additionally, there was mild anxiety in mothers of PID patients. These results are in agreement with Akdag et al., who evaluated anxiety in parents of PID patients during the COVID-19 outbreak and found that it was significantly higher than in parents of healthy children (11). Also, in the study by Sowers and Galantino, anxiety was higher in the pediatric population with PID during the outbreak compared to before the outbreak (12).

In a study conducted by Topal et al. in 2020, anxiety was evaluated in parents of children with PID who had to receive IVIG monthly. They found that these parents had a higher anxiety score than parents of non-PID children (P = 0.003), which contrasts with our study (13). In our study, all patients had inborn errors of immunity, so we expected parents to be concerned about infection in their immunocompromised child. Therefore, regular hospitalization or non-hospitalization did not lead to a significant difference between the two groups.

One of our limitations was the non-availability of anxiety data in the general population in Iran, especially during the outbreak. This emphasizes the need for larger studies conducted in healthy people. Additionally, follow-up studies in immunocompromised patients after the COVID-19 outbreak will be helpful. Comparing the results will illustrate the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of these susceptible populations.

4.1. Conclusions

According to our data, there was mild to moderate anxiety in PID children and mild anxiety in their mothers during the first year of the COVID-19 outbreak. Non-compliance with quarantine significantly led to higher anxiety scores in both groups. Therefore, advice to stay home and more restricted social communication improved mental health.