1. Background

Adolescence is the fastest stage in human development, and the WHO defines it as "a life span between 10 and 19 years old, in which a person moves toward independence and identity" (1-3). Puberty, which involves numerous hormonal, physiological, behavioral, and emotional changes, particularly for females, is the main transition throughout adolescence (1, 4). The onset of secondary sex traits, including pubic hair development, height and weight gain, breast expansion, and menarche—the final stage of puberty—usually occurs between the ages of 12 and 13. Furthermore, because menstruation is linked to dysmenorrhea, discomfort, and heavy bleeding, it is the most stressful event that occurs throughout adolescence (5). Although menstruation is a natural physiological condition that indicates normal reproductive system functioning, it involves physical and emotional changes that cause a sense of tension, embarrassment, and confusion due to a lack of adolescent girls' knowledge about puberty signs and symptoms and how to take care of themselves during menstruation (6, 7).

Accordingly, adolescents feel uncomfortable getting the required information from the public or family about menstruation problems and how to take care of themselves because they consider menstruation a taboo topic (8). On the other hand, the lack of knowledge by parents and society affects the knowledge, attitudes, and self-care behaviors of female adolescents regarding menstruation (9). Therefore, assessing and enhancing adolescent girls' knowledge will create a positive attitude and improve their self-care behaviors during menstruation, leading to decreased morbidity among them (9). Parents and schools have a vital role in educating female adolescents about menstruation. Studies revealed that parents rarely communicate with their daughters about menses at regular intervals, and schools are limited in what they can teach (10).

According to the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), there are about 1.2 billion adolescents worldwide, 85% of whom live in developing countries (11). The Jordanian Department of Statistics reports that 52% of the Jordanian population is under 20 years old (12). Additionally, 25% of Jordanians are adolescents, with 50% of them being female (13). Recent research conducted in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Afghanistan, and Egypt indicates that adolescent girls have adequate knowledge about menstrual hygiene and a varying level of healthy practices during menstruation (14-17). The literature shows that female adolescents, particularly those attending unqualified schools with inadequate supplies of sanitary products, water, and hygiene, lack knowledge about menstruation care practices and information (18). Consequently, increasing the level of awareness among teenage girls is essential for enhancing their quality of life and preventing health issues linked to ignorance and unhealthy menstrual habits (19).

2. Objectives

This study aims to identify the knowledge of adolescent females about menstruation, evaluate their self-care behaviors during menstruation, and assess the relationship between socio-demographic variables and their levels of knowledge and self-care behaviors related to menstruation among female adolescents in three government girls' schools in the Al Karak governorate of Jordan.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design, Duration, Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Jordan at three governmental girls' schools in Al-Mazar Al Janubi, Al Karak governorate, namely, Al Taibah Secondary Girls School, Kholah Bent Al Azowar Elementary School, and Al Gafariah Secondary Girls School, between March 2020 and March 2021.

3.2. Participants

The target population of this study was Jordanian female adolescents attending three government girls' schools in the Al Karak governorate of Jordan. The study sample was selected in two stages using the convenience sampling method. The sample consisted of Jordanian adolescent girls aged 11 to 17 years who had experienced at least two regular menstrual cycles. Adolescent girls with chronic diseases or physical disabilities that prevented them from taking care of themselves were excluded from the study.

3.3. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated using the G*Power program, with a significance level of 0.05, a medium effect size, and a power of 0.80. The required sample size was 55 participants. Considering an attrition rate of 10%, the final sample size was set at 100 girls.

3.4. Study Instruments

A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from the adolescent girls (8). The data collection instrument is composed of three basic parts: (1) personal information: This section collected the participants' personal details, including age, class, place of residence, parents' educational levels, number of sisters, family type, and economic status; (2) knowledge about menstruation: This section consists of nine questions on a three-point scale (yes, no, I don't know). Each item is scored 1 for a correct answer and 0 for an incorrect answer. The total score ranges between 0 and 9, with higher scores indicating a higher level of knowledge about menstruation. Additionally, knowledge about menstrual hygiene is assessed with six questions on the same three-point scale, scored similarly. The total score ranges between 0 and 6, with higher scores indicating a higher level of knowledge about menstrual hygiene; (3) menstrual hygiene practices: This section includes eight items covering aspects such as the type of absorbent used, frequency of washing genitals, bathing frequency, hygiene materials, and disposal method practices. Correct answers are scored as 1, and incorrect answers are scored as 0. The highest possible score is 8, indicating excellent self-care behavior, while the lowest possible score is 0, indicating poor self-care behavior.

3.5. Instrument Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire demonstrated reliability and validity, with good internal consistency indicated by a Cronbach's Alpha value of 0.820 for the entire instrument. Internal validity was assessed, and all items of the questionnaire had a P-value of less than 0.05, indicating consistency across all items in each domain (8). Additionally, content validity was confirmed by two nursing experts.

3.6. Data Collection Procedures

The data collection process began after obtaining the necessary approvals. School directors were contacted to facilitate access to students and to provide an appropriate place to meet with them. The researcher then met with the selected students who met the inclusion criteria, explained the goal of the study, and informed them of their rights to continue or withdraw from the study. After obtaining the required consent, data was collected by the researcher using the questionnaire. Explanations were provided to students who had difficulties completing the questionnaire.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the IRB Committee of Al Balqa Applied University (reference number: 2024/2023/3/16), the Jordanian Ministry of Education (MOE), and the education directorate of Al Mazar Al Janubi in Al Karak city. Two consent forms were signed by the participating girls and their parents to ensure their understanding and agreement to allow their daughters to participate in the study. The researcher provided an explanation of the study's goals, risks, and advantages to the girls and their families, guaranteeing confidentiality and anonymity.

3.8. Data Analysis

Data was entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic characteristics, knowledge scores, and menstrual hygiene practice scores. Inferential statistics, primarily t-tests and one-way ANOVA, were also used to analyze the data. Additionally, Pearson correlation (r) was used to assess the association between variables of interest.

4. Results

A total of 100 school-adolescent female students from three governmental girls' schools in Al-Karak governorate participated in the study, with a mean age of 15.83 ± 1.43 years, ranging from 11 to 17 years old. The majority of the students' parents had a high school education level (fathers, N = 45, 45%; and mothers, N = 55, 55%). More than three-quarters of the sample indicated that their family's economic status was sufficient to meet their needs and ensure well-being (N = 65, 65%). Regarding the source of knowledge about the menstrual cycle, multiple response analysis showed that the vast majority of female students gained information from their mothers (74%), followed by school (34%). The median number of older sisters in the family was 2. The mean age of the first occurrence of menstruation was 13.84 ± 0.89 years, ranging from 11 to 17 years old (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Father’s education level | |

| Less than high school | 34 (34) |

| High school | 45 (45) |

| University degree | 21 (21) |

| Mother’s education level | |

| Less than high school | 20 (20) |

| High school | 55 (55) |

| University degree | 25 (25) |

| Family economic situation | |

| The family's needs are not always met | 15 (15) |

| The family's needs are sometimes met | 20 (20) |

| The family's needs and well-being are always met | 65 (65) |

| Number of your sisters who are older than you | Md = 2 |

| Age | 15.83 ± 1.43 (11 - 17) |

| My source of knowledge about the menstrual cycle | |

| Mother | 74 (74) |

| Father | 8 (8) |

| Sister | 32 (32) |

| Friends | 25 (25) |

| School | 34 (34) |

| Network | 27 (27) |

| Age at first occurrence of menstrual period | 13.84 ± 0.89 (11 - 17) |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD (range).

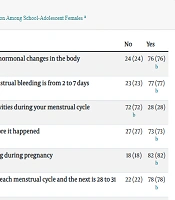

Table 2 ranks the levels of knowledge about menstruation. Generally, the total mean score on the knowledge scale was 6.23 ± 2.03 out of 9. This revealed that 55% of the participants had a good knowledge level, 28% had a moderate knowledge level, and 17% had a poor knowledge level regarding menstruation.

| Item Description | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Menstruation occurs due to hormonal changes in the body | 24 (24) | 76 (76) b |

| 2. The normal duration of menstrual bleeding is from 2 to 7 days | 23 (23) | 77 (77) b |

| 3. You should avoid sports activities during your menstrual cycle | 72 (72) b | 28 (28) |

| 4. I knew about my period before it happened | 27 (27) | 73 (73) b |

| 5. A woman stops menstruating during pregnancy | 18 (18) | 82 (82) b |

| 6. The normal period between each menstrual cycle and the next is 28 to 31 days | 22 (22) | 78 (78) b |

| 7. The normal age for menstruation to occur is for a girl to be less than 16 years old | 32 (32) | 68 (68) b |

| 8. The source of menstrual blood is the uterus | 50 (50) | 54 (54) b |

| 9. Bathing on the first day of the menstrual cycle is good and does not harm health | 67 (67) | 33 (33) b |

| Total mean score | 6.23 ± 2.03 out of 9 | |

| Levels of knowledge about menstruation based on percentage of maximum possible scores (20, 21) | ||

| Poor (0 - 50) | 17 (17) | |

| Fair (51 - 75) | 28 (28) | |

| Good (76 - 100) | 55 (55) | |

a Values are expressed as No (%) or mean ± SD.

b Correct answer.

In addition, the vast majority of the sample demonstrated high proportions of correct answers regarding knowledge about menstrual hygiene management. The mean score for knowledge about menstrual hygiene management was 5.74 ± 1.13 out of 6, with 80% of participants demonstrating a good knowledge level (Table 3).

| Item Description | Values | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Hygiene during the menstrual cycle means that the genital area is clean, use sanitary pads, and dispose of them correctly | 6 (6) | 94 (94) b |

| 2. Maintaining hygiene during the menstrual cycle protects against infection and avoids bad smell | 5 (5) | 95 (95) b |

| 3. The best way to absorb menstrual blood is non-recyclable sanitary pads useable and disposable | 7 (7) | 93 (93) b |

| 4. The genital area should be washed with water every time the pad is changed | 8 (8) | 92 (92) b |

| 5. The sanitary pad should be changed at least three or more times during the day | 10 (10) | 90 (90) b |

| 6. Bathing during menstruation is harmful to health | 18 (18) b | 82 (82) |

| Total mean score (out of 6) | 5.74 ± 1.13 | |

| Levels of knowledge about menstruation hygiene management based on a percentage of maximum possible scores (20, 21) | ||

| Poor (0 - 50) | 12 (12) | |

| Fair (51 - 75) | 8 (8) | |

| Good (76 - 100) | 80 (80) | |

a Values are expressed as No (%) or mean ± SD.

b Correct answer.

The results in Table 4 demonstrate good hygienic practices during the menstrual cycle. All participants used sanitary napkins during their menstrual period; 90% changed the pad three times or more per day, and 98% disposed of the pads in the basket after use. Concerning body hygiene during the menstrual cycle, a large proportion of participants washed their genitals during the period (100%), and 77% cleaned the genital area four times or more daily. Only 32% used soap and detergents with water to wash the area, and 68% took showers on an irregular basis or less than once a day (82.3%). The mean scale score was 6.86 ± 0.87 out of 8, with most participants (68%) demonstrating fair menstrual hygiene management practices.

| Item Description | Values |

|---|---|

| 1. Which of the following methods do you use during your menstrual cycle? | |

| Sanitary napkin pad | 100 (100.0)b |

| 2. Number of times you change your pad during the day | |

| Less than three times | 10 (10) |

| Three or more times | 90 (90)b |

| 3. I dispose of pads after use by | |

| I put it in the basket b | 98 (98)b |

| I put it on the toilet seat and then pour water | 2 (2) |

| 4. Do you wash your genitals during your menstrual cycle | |

| Yes | 100 (100)b |

| No | 0 (0.0) |

| 5. How often do you wash your genitals | |

| Less than four | 33 (33) |

| Four and more | 77 (77)b |

| 6. What materials do you use to wash the genitals during the menstrual cycle? | |

| Soap and water | 32 (32)b |

| Water only | 52 (52) |

| Water-based soap and disinfectant | 16 (16) |

| 7. Do you shower during menstruation | |

| Yes | 68 (68)b |

| No | 32 (32) |

| 8. If yes how many times do you shower during menstruation (N = 68) | |

| At least once a day | 12 (17.6)b |

| Irregular or less than once a day | 56 (82.3) |

| Total mean score (out of 8) | 6.86 ± 0.86 |

| Levels of menstrual hygiene management based on percentage of maximum possible scores | |

| Poor (0 - 50) | 7 (7) |

| Fair (51 - 75) | 68 (68) |

| Good (76 - 100) | 25 (25) |

a Values are expressed as No (%) or mean ± SD.

b Correct answer.

The results revealed that none of the school-adolescent females' socio-demographic data had an association with knowledge about menstruation (P > 0.05 for all). Moreover, Table 5 showed that school-adolescent females' age was the only significant positive factor associated with their knowledge about menstrual hygiene management (r = 0.328, P = 0.007). Furthermore, menstrual hygiene management practices were significantly positively associated with the number of older sisters (r = 0.386, P < 0.001), as shown in Table 5.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Test Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Differences of Knowledge About Menstruation Hygiene Management Based on School-Adolescent Females’ Socio-Demographical Data | |||

| Father’s education level | 0.928 | 0.501 | |

| Less than high school | 5.2.00 ± 0.30 | ||

| High school | 5.62 ± 1.27 | ||

| University degree | 4.87 ± 1.60 | ||

| Mother’s education level | 1.337 | 0.290 | |

| Less than high school | 5.17 ± 1.39 | ||

| High school | 4.55 ± 1.29 | ||

| University degree | 4.78 ± 1.13 | ||

| Family economic situation | 0.654 | 0.488 | |

| The family's needs are not always/or sometimes met | 4.53 ± 2.23 | ||

| The family's needs and well-being are always met | 4.80 ± 0.98 | ||

| Number of your sisters who are older than you | -0.024 | 0.850 | |

| Age | 0.328 | 0.007 | |

| Age at first occurrence of menstrual period | 0.042 | 0.963 | |

| Mean Differences of Menstrual Hygiene Management Practices Based on School-Adolescent Females’ Socio-Demographical Data | |||

| Father’s education level | 1.585 | 0.311 | |

| Less than high school | 5.57 ± 0.95 | ||

| High school | 5.93 ± 0.84 | ||

| University degree | 6.0 ± 0.68 | ||

| Mother’s education level | 0.424 | 0.925 | |

| Less than high school | 5.67 ± 0.98 | ||

| High school | 6.81 ± 0.95 | ||

| University degree | 5.91 ± 0.67 | ||

| Family economic situation | 0.933 | 0.454 | |

| The family's needs are not always/or sometimes met | 6.30 ± 0.93 | ||

| The family's needs and well-being are always met | 5.76 ± 0.84 | ||

| Number of your sisters who are older than you | 0.386 | 0.001 | |

| Age | -0.126 | 0.382 | |

| Age at first occurrence of menstrual period | 0.004 | 0.977 | |

4.1. Summary of Statistical Analysis

The current study showed that 55% of participants had good knowledge of menstruation. Additionally, the vast majority of participants (80%) demonstrated a good knowledge level of menstrual hygiene management, and most of them (68%) had fair menstrual hygiene management practices.

5. Discussion

The primary and final sign of puberty in teenagers is the menstrual cycle, which is linked to feelings of stress, anxiety, and humiliation. Adolescent female health is significantly impacted by knowledge about menstruation and clean menstrual behaviors. The current study investigated the level of knowledge of adolescent females about menstruation, evaluated their self-care behaviors during menstruation, and assessed the relationship between socio-demographic variables and their levels of knowledge and self-care behaviors among female adolescents in three government girls' schools in the Al Karak governorate of Jordan.

According to the study results, the highest educational level for mothers and fathers in this study was high school (55% and 45%, respectively). These results align with Bahari et al.'s (22) findings that the highest mother and father educational levels are high school (50%) and (44%), respectively. Tork also reported this (23), finding that more than 60% of adolescents' mothers had a high school education. The main source of information about menstruation for adolescent girls was their mothers (74%); this result is consistent with the findings of a study conducted on females aged 10 - 19 years that showed one-quarter of participants stated that mothers are the main source of information for female adolescents about puberty (22). Solehati and Kosasih (9) also reported that the mother is the main source of sexual reproduction and puberty information. Fathers were chosen by only 8% of participants, which is logical due to the sensitivity of the topic.

The current study showed that half of the adolescent female students (55%) had a good level of knowledge about menstruation. This result is consistent with a cross-sectional study conducted in central Ethiopia, which revealed that three-fourths of adolescents had good overall knowledge regarding menstruation (24). In contrast, a cross-sectional descriptive survey among adolescent girls in selected schools of Chitwan revealed that one-third of teenage girls had inadequate knowledge of menstruation (25). Another community-based cross-sectional study, consisting of 150 girls from the Munda tribe aged 13 - 18 years, showed poor knowledge about menstruation among tribal adolescent girls, with practices influenced by various myths and misconceptions (26). Additionally, the majority of the study sample (76%) reported that menstruation is due to hormonal changes in the female body and knew the normal period between menstrual cycles, which is 2 - 7 days (77%). Alshurafa (8) reported similar findings, with 86.4% of participants indicating that menstruation is due to hormonal changes and 73% knowing the interval between menstrual cycles.

The current study also showed that most participants had good knowledge about menstrual hygiene management (80%). A cross-sectional survey conducted among 441 schoolgirls in Mekidela city revealed that two-thirds of respondents had good knowledge and good practice of menstrual hygiene management (27). Another study among 397 schoolgirls aged 12 - 17 years, selected by a multistage sampling technique from governmental preparatory and secondary schools in the Gaza Strip, showed that half of the participants (53.4%) expressed good menstrual hygiene practices. Furthermore, 90% of participants changed sanitary pads three to four times per day during menstruation, contrasting with Yadav et al.'s (28) findings that only 39% changed pads every four to six hours. About 82% believed that bathing during menstruation was harmful to health, contrary to the results shown by Boakye-Yiadom et al. (29), where the majority of their sample (52.1%) bathed twice a day during menstruation.

About two-thirds of participants had a fair level of menstrual hygiene practices (68%). All female participants used sanitary napkins during menstruation (100%); these findings were not congruent with the findings of Boakye-Yiadom et al. (29) and Bulto (24). The results reflect that the adolescent girls had good hygiene practices. All participants washed their genitalia during periods, which contradicts Nelapati's (30) conclusion that only 55% of his sample did so. Additionally, about 68% of girls took showers during their periods, which is consistent with Abed and Yousef's (17) findings that 89% took showers during their menstrual periods.

Several studies have documented that poor knowledge regarding the menstrual cycle may be due to society’s view that the menstrual cycle is a shameful and sensitive topic (31, 32). Therefore, due to cultural constraints, it is a sensitive topic that is forbidden to be discussed in some societies (31, 32). In this study, there is no association between female adolescents' demographic variables and the level of participants' knowledge about menstruation. In contrast to Abed and Yousef's (17) findings, the level of knowledge about menstruation was higher among adolescent girls in urban areas with a high level of education. In the same context, age and the number of sisters older than the participant are the only socio-demographic variables that are positively associated with menstrual hygiene management and the level of hygienic practices during menstruation, respectively. Belayneh and Mekuriaw (31) found that girls younger than 15 years old, longer days of menstrual flow, and poor knowledge about menstruation are associated with poor menstrual hygiene practices.

5.1. Limitations and Future Recommendations

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size used in this study affects the ability to generalize the findings to other populations. Second, the sample was drawn from a single location in Jordan, so the findings may not be generalizable to all populations in Jordan or other settings. Third, the researcher utilized a convenience sample rather than a random sample, which increases the possibility of bias. Lastly, the participants filled out the questionnaire in the presence of researchers, which may have led to socially desirable responses. Further studies are needed to address these limitations.

5.2. Conclusions

Adolescence is a vital period in human life, particularly for females. According to the findings of this study, adolescent schoolgirls in Al Karak City, Jordan, have a good level of knowledge about menstruation and menstrual hygiene management and demonstrate satisfactory hygienic practices during menstruation. Mothers are the primary source of information regarding menstruation and menstrual health practices. The age and number of older sisters of the participants are significant factors affecting menstrual hygiene management and practices. It is critical to recognize the need for education on healthful menstruation behaviors. Menstrual hygiene education should also be emphasized in the media. Therefore, policymakers and other stakeholders should establish health education programs to raise awareness and encourage the adoption of proper menstrual hygiene practices.