1. Background

Febrile neutropenia (FN) is one of the most important complications in pediatric patients undergoing chemotherapy for their underlying malignancies (1). During FN episodes, patients are potentially at risk of bacterial infections, ranging from mild to severe (2, 3), which can increase mortality and morbidity in individuals with hematologic malignancies (4). In clinical practice, most children who develop chemotherapy-induced neutropenia associated with fever are immediately hospitalized for further diagnostic evaluation and empiric therapy with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics until resolution of fever and recovery of absolute neutrophil count (ANC) (5). This approach leads to increased length of hospital stay, drug resistance, nosocomial infections, overtreatment, emotional burden on patients and parents, and increased costs for families and the healthcare system (6, 7). Additionally, FN can potentially occur due to viral infections, blood transfusions, drugs, and the underlying malignancy, and hence, an aggressive approach to such patients may not always be necessary (7).

To reduce the morbidities and costs associated with the management of FN episodes, clinical practice guidelines strongly recommend oncologists incorporate validated risk stratification models into the routine clinical management of FN patients (8). According to various systematic reviews, many prediction rules have been used to stratify FN pediatric patients into high- and low-risk groups for invasive bacterial infections based on predictive factors such as the type of underlying malignancy, patients' clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory markers, and chemotherapy regimen (9-13). However, no single prediction rule can be universally recommended due to differences in study populations, the definition of outcomes, included risk factors, and statistical methods (14, 15).

According to a recent guideline, risk prediction rules for FN patients should be locally validated before being used in a specific geographical and healthcare setting (14). This is particularly important in developing countries where healthcare resources are limited and social security coverage is low (16). So far, no risk prediction model has been used in the Iranian pediatric population.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to determine the clinical and para-clinical predictors of fever duration in FN episodes in Iranian pediatric oncology patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Characteristics

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2016 to January 2018 at Bahrami Children’s Hospital, Tehran, managed by the Blood Department. The study population consisted of admitted children with FN undergoing chemotherapy for hematological or non-hematological malignancies. Sampling was done using a simple method, and the sample size was determined using the variable of pulmonary infection (33%) from the Bakhshi et al.’s study and the Cochran’s formula (α = 0.05, d = 0.2P) (2). All available patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.CHMC.REC.1400.163). The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were observed throughout the study.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study population consisted of admitted children with FN undergoing chemotherapy for hematological or non-hematological malignancies. Only patients with a single oral temperature of 38.3°C or at least two oral temperatures ≥ 38°C within one hour and an ANC ≤ 1500/µL at the time of admission were included in the study (1). Confounding variables that may cause bias were included in the study’s exclusion criteria. Children who developed an FN episode during hospitalization, had a history of recent allogeneic stem cell transplantation, or had an apparent source of infection at the time of admission (e.g., acute gastroenteritis and acute otitis media) were excluded.

3.3. Patient Management

After obtaining a detailed history and a complete physical examination, the children were admitted to hematology-oncology wards and managed according to our FN management guidelines (17). Laboratory tests included hemoglobin level, total leukocyte count (TLC), ANC, platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Blood, urine, and central catheter cultures were also obtained, and a chest radiograph was performed. After obtaining the cultures, the patients were treated empirically with intravenous amikacin 5 mg/kg and ceftazidime 50 mg/kg every 8 hours. In FN patients with an indwelling portal catheter, hemodynamic instability, chemotherapy-induced mucositis, those admitted during the first 48 hours following prior discharge, or those who received fluoroquinolones as prophylaxis, amikacin was replaced with vancomycin 15 mg/kg every 6 hours. In the case of persistent fever despite 120 hours of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, empiric antifungal therapy was started.

3.4. Study of Variables

The outcome variable was defined as the duration of fever, categorized as < 72 hours, 72 - 120 hours, and > 120 hours. The independent predictive variables included age, gender, underlying malignancy (hematologic/non-hematologic), the time interval between the last session of chemotherapy and initiation of FN, oral temperature, patients’ general condition (classified as poor; poor general condition defined as altered consciousness, unstable vital signs, hypoxia, and inability to maintain oral intake), indwelling portal catheter, hemoglobin level, TLC, ANC (further categorized as mild, 1000 - 1500/µL; moderate, 500 - 1000/µL; severe, < 500/uL), platelet count, ESR, CRP, positive cultures (blood, urine, central catheter), and changes in the chest radiograph.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 21 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive data were presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was used to determine the independent variables associated with the study outcome. The potential predictors statistically associated with the duration of fever were selected for ordinal regression analysis. A collinearity test was used to determine any strong correlation among the predictor variables. The model’s goodness-of-fit was also determined. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Patients’ Characteristics

From January 2016 to January 2018, a total of 180 episodes of FN in children with underlying malignancy who met the inclusion criteria were recruited into the study. Ninety-six (53.3%) of the participants were boys, with a mean age of 5.48 ± 3.44 years (ranging from 1 to 16 years). The most common malignancies were of the hematological type, with acute lymphoblastic leukemia contributing to 60%. All patients had an oral temperature ≥ 38ºC and ANC ≤ 1500/µL at presentation. A total of 26 (14.4%) patients had a documented infection, revealed by having at least one positive blood, urine, or catheter culture. The majority of patients (59.4%) achieved defervescence during the first 72 hours after admission. In 23.9% of patients, fever resolved during the 72-120 hour period after admission. Thirty patients (16.7%) were still febrile after 120 hours of hospitalization. Clinical and paraclinical characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameters | N | Mean ± SD | Min - Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 180 | 5.4 ± 3.44 | 1 - 16 |

| Oral temperature (°C) | 180 | 38.5 ± 0.43 | 38 - 40 |

| Time since last chemotherapy session (d) | 172 | 12.6 ± 21.78 | 0 - 240 |

| WBC (mL) | 180 | 1117 ± 818.25 | 100 - 5800 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 180 | 8.9 ± 2.04 | 3 - 14.5 |

| PLT (103/mm3) | 180 | 118.5 ± 105.16 | 3 - 468 |

| ANC (mL) | 44 | 647.18 ± 454.94 | 16 - 1500 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 180 | 54.3 ± 35.38 | 2 - 136 |

| Gender (n = 180) a | |||

| Male | 96 (53.3) | - | - |

| Female | 84 (46.7) | - | - |

| Underlying malignancy (n = 180) a | |||

| Hematological | 138 (76.7) | - | - |

| Non-hematological | 42 (23.3) | - | - |

| Indwelling portal catheter (n = 180) a | |||

| Yes | 29 (16.1) | - | - |

| No | 151 (83.9) | - | - |

| Patients’ general condition (n = 180) a | |||

| Fair | 121 (67.2) | - | - |

| Poor | 59 (32.8) | - | - |

| Chest radiograph changes (n = 180) a | |||

| Yes | 35 (19.4) | - | - |

| No | 145 (80.6) | - | - |

| Grade of neutropenia (n = 180) a | |||

| Mild | 13 (7.2) | - | - |

| Moderate | 38 (21.1) | - | - |

| Severe | 129 (71.7) | - | - |

| Blood culture (n = 180) a | |||

| Positive | 24 (13.3) | - | - |

| Negative | 156 (86.7) | - | - |

| Catheter lumen culture (n = 180) a | |||

| Positive | 8 (4.4) | - | - |

| Negative | 172 (95.6) | - | - |

| Urine culture (n = 180) a | |||

| Positive | 3 (1.7) | - | - |

| Negative | 177 (98.3) | - | - |

Abbreviations: N, number of patients; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.2. Predictors of Fever Duration

According to the univariate analyses, there was a statistically significant association between the duration of fever and body temperature, general condition, indwelling portal catheter, ANC, degree of neutropenia, hemoglobin, platelet count, serum CRP > 90, positive blood culture, positive catheter culture, having at least one positive culture, and chest radiograph changes (Table 2). The collinearity test revealed a strong correlation between ANC and the grade of neutropenia, as well as between blood culture, urine culture, portal catheter culture, and having at least one positive culture. To avoid estimation problems, the grade of neutropenia and having at least one positive culture were used in the final ordinal regression model as they explained more of the variability in the outcome variable.

| Parameters | Duration of Fever | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 72 h (n = 107) | 72 - 119 h (n = 43) | ≥ 120 h (n = 30) | ||

| Sex | 0.642 | |||

| Male | 57 (53.3) | 21 (48.8) | 18 (60) | |

| Female | 50 (46.7) | 22 (51.2) | 12 (40) | |

| Age (y) | 5.69 ± 3.28 | 5.48 ± 4.03 | 4.54 ± 2.65 | 0.339 |

| Underlying malignancy | 0.96 | |||

| Hematological | 84 (60) | 33 (23.6) | 23 (16.4) | |

| Non-hematological | 23 (57.5) | 10 (25) | 7 (17.5) | |

| Indwelling portal catheter | 0.003 | |||

| Yes | 14 (13.1) | 4 (9.3) | 11 (36.7) | |

| No | 93 (86.9) | 39 (90.7) | 19 (63.3) | |

| General condition | 0.000 | |||

| Fair | 91 (85) | 26 (60.5) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Poor | 16 (15) | 17 (39.5) | 26 (86.7) | |

| Last chemotherapy sessionmedian IQR (d) | 8 (6-13) | 7 (6-13) | 7 (2.5-9.5) | 0.189 |

| Oral temperature (°C) | 38.37 ± 0.38 | 38.71 ± 0.45 | 38.74 ± 0.43 | 0.000 |

| Chest radiograph changes | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 13 (12.14) | 6 (13.9) | 14 (46.7) | |

| No | 91 (85.0) | 37 (86.0) | 16 (53.3) | |

| WBC (/mL) | 1145.79 ± 714.972 | 1206.28 ± 1109.946 | 886.67 ± 640.438 | 0.222 |

| ANC (/mL) | 638.27 ± 348.99 | 591.16 ± 326.124 | 414.7 ± 221.79 | 0.005 |

| Grade of neutropenia | 0.000 | |||

| Mild | 13 (12.1) | 4 (9.3) | 1 (3.33) | |

| Moderate | 52 (48.6 | 14 (32.6) | 3 (10) | |

| Sever | 42 (39.3) | 25 (58.1) | 26 (86.66) | |

| Hb (mg/dL) | 9.14 ± 1.95 | 8.9 ± 2.01 | 7.92 ± 2.18 | 0.014 |

| PLT (103/mm3) | 132.58 ± 103.04 | 130.88 ± 117.94 | 50.86 ± 60.16 | 0.000 |

| CRP (g/L) | 46.5 ± 34.8 | 61.4 ± 32.6 | 75.3 ± 31.3 | 0.000 |

| Blood culture | 0.001 | |||

| Positive | 7 (6.5 | 7 (16.3) | 10 (33.3) | |

| Negative | 100 (93.5) | 36 (86.7) | 20 (66.7) | |

| Catheter lumen culture | 0.000 | |||

| Positive | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) | 6 (20) | |

| Negative | 106 (99.1) | 42 (97.7) | 24 (80) | |

| Urine culture | 0.615 | |||

| Positive | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Negative | 106 (99.1) | 42 (97.7) | 29 (80) | |

| At least one positive culture | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 8 (7.5) | 7 (16.3) | 11 (36.7) | |

| No | 99 (92.5) | 38 (83.7) | 19 (63.3) | |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

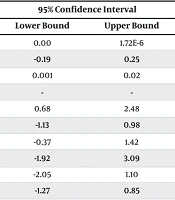

The final model, referred to as the general model with influencing variables denoted as X, was statistically significant (P < 0.05) when compared to the intercept-only model. The intercept-only model is a regression model that does not take into account the main and secondary variables of the study. This indicates that the variables listed in Table 3 have an impact on the duration of fever. Furthermore, the proposed model, along with the results from the ordinal regression analysis, demonstrates a goodness-of-fit (Χ2 = 310, with P = 0.885), indicating the suitability of the model. Table 3 demonstrates that several variables, including CRP, body temperature, general condition, positive culture, and neutropenia levels, significantly impact the duration of fever (P < 0.05). For example, a one-degree increase in fever temperature leads to a 1.369-step increase in the duration of fever (transitioning from 72 > hours to 119 - 72 hours or from 119 - 72 hours to ≥ 120 hours). Additionally, a poor general condition is associated with a 1.392-step increase in the duration of fever compared to a good general condition.

| Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Platelet | -2.796E-6 | 2.304E-6 | 0.00 | 1.72E-6 | 0.225 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.056 | 0.114 | -0.19 | 0.25 | 0.621 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.040 |

| Temperature | 1.369 | 0.498 | - | - | 0.006 |

| Poor general condition vs. good general condition | 1.392 | 0.612 | 0.68 | 2.48 | 0.020 |

| Portal catheter + vs. portal catheter- | 0.139 | 0.502 | -1.13 | 0.98 | 0.782 |

| CXR changes + vs. CXR changes- | 0.806 | 0.468 | -0.37 | 1.42 | 0.085 |

| At least 1 positive culture vs. no positive culture | 1.692 | 0.607 | -1.92 | 3.09 | 0.005 |

| Severe neutropenia | -1.193 | 0.464 | -2.05 | 1.10 | 0.010 |

| Moderate neutropenia vs. mild neutropenia | -0.747 | 0.701 | -1.27 | 0.85 | 0.287 |

5. Discussion

Children with FN are a heterogeneous group at risk of severe infections and their complications. Recently, there has been much emphasis on risk stratification of FN patients based on the early prediction of adverse outcomes so that children categorized as low-risk (according to validated prediction rules) can be treated less aggressively with a better quality of life, even on an outpatient basis (5-9). In this regard, several studies have been conducted to develop models for predicting adverse outcomes, mainly severe infection and/or mortality in pediatric FN patients; however, validated predictive scores and algorithms are still lacking and urgently needed (1-16, 18). Persistence of fever is one of the criteria for changing antibiotics or adding antifungal drugs. To our knowledge, very few studies have investigated the predictive factors of fever duration as the main adverse outcome in children with FN.

In the present study, the risk factors related to prolonged fever in children with FN were investigated in two centers. In general, although most episodes of FN are assumed to result from an infection, blood cultures were positive in less than a third of febrile neutropenic episodes (18). Similar to the literature, the present study had a bacteremia rate of 21%. It should be noted that other factors such as viral infection, blood products, and chemotherapy agents can also cause fever in neutropenic children (2). Phillips et al. reported that a history of more than two previous episodes of FN, abnormal chest radiograph, and being on oral antibiotic therapy at presentation could predict invasive bacterial or fungal infection and/or mortality in children with FN (10).

According to Haeusler et al., the advanced stage of underlying malignancy, concomitant comorbidities, and bacteremia could predict mortality in children with FN (11). Gurlinka et al. found that laboratory markers, namely thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 50,000) and serum CRP (> 90 mg/L), were predictors of mortality in the FN population (13). On the other hand, Lehrnbecher et al. published findings showing that white blood cell (WBC) counts, ESRs, and ANCs do not differ significantly between fever of unknown origin and documented infection in FN (14).

In our study, despite the initial associations found between the duration of fever, patient’s general condition, indwelling portal catheter, ANC, degree of neutropenia, hemoglobin, platelet count, serum CRP, positive blood culture, positive catheter culture, having at least one positive culture, and chest radiograph changes, the ordinal regression analysis revealed that only higher serum CRP (> 90 mg/L), patients' poor general condition, higher oral temperature at presentation, having at least one positive culture, and severe neutropenia (ANC < 500/uL) could significantly predict the duration of fever in neutropenic children with underlying malignancy.

Regarding the association of high CRP (> 90 mg/L) with the duration of fever and response to initial treatment, the results were consistent with the Gurlinka et al. study (13). It is noted that none of the other risk factors in our study were found to be significant predictors of fever duration in the study of Gurlinka et al. (13).

5.1. Conclusions

Febrile neutropenia is a common and serious complication in pediatric oncological patients undergoing chemotherapy, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. The present study aimed to identify prognostic risk factors for FN, specifically in terms of fever duration. According to our findings, several factors, including serum CRP levels, the overall condition of the patients, initial oral temperature, positive culture result, and neutropenia grade, were found to be significant predictors of fever duration. These factors can be utilized in the risk stratification of children with FN. However, it is important to note that our study had a limited sample size, which is a notable limitation. To further investigate risk factors and develop accurate treatment guidelines based on risk prediction, it is recommended to conduct larger and more comprehensive studies.