1. Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), and unspecified IBD, is an autoimmune disorder affecting the gastrointestinal tract. Although the exact etiology of IBD remains unclear, an overactive gut microbiota has been suggested as a contributing factor to its development (1). Approximately one-quarter of all IBD diagnoses occur in childhood or adolescence (2). Genetic predisposition, immune system dysregulation, and microbial dysbiosis are believed to play roles in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory bowel disorders (3, 4).

Very early onset inflammatory bowel disease (VEO-IBD) is diagnosed in children who develop the disease before the age of six (5). According to the pediatric Paris classification, childhood-onset IBD was previously categorized into two age groups: Children aged 10 - 17 years and those under 10 years (6). More recent classifications further divide early-onset pediatric IBD into very early-onset (under six years), infantile (under two years), and neonatal (within 28 days) categories (7). While VEO-IBD represents a small proportion of chronic IBD cases, it is the fastest-growing segment (8). It is frequently associated with pancolitis (9), a positive family history (10, 11), and a severe disease course that may lead to mortality (12). Monogenic causes, often linked to primary immunodeficiencies, are considered major contributors to this early onset. Genetic defects associated with VEO-IBD include epithelial barrier dysfunction, phagocytic defects, hyperinflammatory disorders, degenerative B and T cell disorders, and immune system abnormalities, such as IL10 signaling defects (7, 13, 14).

The incidence of IBD is rising among pediatric patients (15-17). Approximately three million Americans are affected by IBD (18), with around 25% of cases diagnosed in childhood or adolescence (19). The VEO-IBD accounts for 3 - 15% of pediatric IBD cases (20). Both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms are commonly observed in patients with VEO-IBD. Gastrointestinal manifestations may include bloody or mucus-containing diarrhea, frequent vomiting, failure to thrive, and anal skin tags or fistula formation. Extraintestinal symptoms can involve intermittent fever, arthritis, arthralgia, folliculitis, uveitis, and various skin conditions (21-23).

Pediatricians and gastroenterologists frequently consider differential diagnoses such as cow’s milk protein intolerance, food allergies, infections, celiac disease, and inadequate calorie intake before confirming a chronic IBD diagnosis. However, it is crucial to include VEO-IBD in the differential diagnosis to avoid delays in treatment (15, 24, 25).

Subclinical hearing loss refers to a form of hearing impairment that remains undetectable by standard audiometric tests but can still impact hearing acuity (26). Symptoms may include difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments or experiencing a sensation of muffled hearing (27). In this study, subclinical hearing loss was characterized by abnormal otoacoustic emissions (OAE) or auditory brainstem responses (ABR) despite normal hearing thresholds in standard audiometry. The presence of subclinical sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in association with IBD has been examined in only two early studies, though isolated case reports describe sudden symptomatic hearing loss in IBD patients (28).

The IBD may also affect the inner ear as an extraintestinal manifestation. Autoimmune diseases such as vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Kogan syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and rheumatoid arthritis have been associated with auditory dysfunction (28, 29). Multiple case reports have described acute hearing loss occurring either during an active disease phase or as an early manifestation of IBD (30-34). Sensorineural hearing loss in these patients is typically bilateral, with a sudden onset and rapid progression during both active and quiescent phases of intestinal disease. Early initiation of immunosuppressive therapy is crucial to prevent irreversible SNHL caused by inflammatory damage to the sensory components of the inner ear (30, 35, 36).

To date, only two preliminary studies have investigated the presence of subclinical SNHL associated with IBD, aside from isolated case reports where hearing loss typically develops during active disease progression (37).

2. Objectives

Given the established impact of IBD on hearing function and the increasing incidence of VEO-IBD in the neonatal population (8), this study aims to explore the potential relationship between VEO-IBD and hearing impairment in Iranian infants. If a significant correlation is identified, these findings may contribute to improved diagnostic and prognostic approaches in clinical practice.

3. Methods

From February 2022 to May 2023, 25 consecutive patients with VEO-IBD were enrolled in the study at Mofid Hospital. The study cohort included 13 boys and 12 girls, all aged between birth and six years. The control group comprised 30 healthy children, matched for age and gender, with no history of gastrointestinal disorders or hearing impairments. These control participants were selected from the general pediatric population attending routine check-ups at Mofid Hospital.

We recorded all patient characteristics, including disease duration, type, site of involvement, and medication history, specifically immunosuppressive drugs, along with their duration and dosages at the time of the study. Additionally, extraintestinal manifestations (EIM) associated with VEO-IBD were documented. Evaluations were conducted before the initiation of any medical intervention and immediately following diagnosis by a specialist using colonoscopy. Colonoscopy served as the primary diagnostic tool to assess the condition of the colon and rectum, ensuring an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning.

None of the patients had a history of ototoxic drug use, head trauma, or noise exposure, apart from head trauma, noise exposure, and family history of hearing loss.

All parents provided written informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the study protocol. The study was approved by the local ethics committee in accordance with the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (IR.sbmu.msp.rec.1400.028).

3.1. Subgroup Analysis

3.1.1. Disease Duration and Phase

The patients were categorized based on the duration of their VEO-IBD, distinguishing between acute (less than six months), chronic (six months to two years), and long-term (more than two years) phases. This classification was essential in assessing the impact of disease duration on hearing function.

3.1.2. Disease Type

Subgroups were formed based on the type of VEO-IBD, specifically differentiating between CD and UC.

3.1.3. Site of Involvement

Further categorization was conducted based on the specific gastrointestinal sites affected, such as the colon and ileum.

3.1.4. Age and Gender Distribution

The mean age and standard deviation were calculated for each subgroup. The distribution of males and females within each category was also recorded.

3.1.5. Demographic Data

For subgroup analysis, the average age of patients diagnosed with CD was 3.5 years with a standard deviation of 1.2 years. This group comprised 7 males and 5 females. In contrast, the subgroup of patients with UC had an average age of 4.0 years with a standard deviation of 1.5 years, including 8 males and 6 females.

These age and gender distributions provide a comprehensive overview of the study population, facilitating a better understanding of how these factors might influence the potential relationship between VEO-IBD and hearing function.

3.2. Testing Protocol

In this study, tympanometry and acoustic reflex testing were performed to evaluate middle ear function. Tympanometry was conducted using a GSI TympStar Pro device, manufactured in Denmark, in a soundproof room. The procedure involved the use of a 100 Hz probe tone to measure peak compliance pressure, aiding in the identification of middle ear effusion or eustachian tube dysfunction.

For acoustic reflex testing, an Interacoustics Titan device, also manufactured in Denmark, was utilized. The protocol included measuring acoustic reflex thresholds ipsilaterally and contralaterally using probe stimuli, such as single-frequency tones or broadband noise. Impedance was maintained below 5 kilo-ohms during testing, and reflexes were measured at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. The lowest intensity at which a reflex was observed was recorded as the acoustic reflex threshold.

In addition to distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) screening, ABR threshold tracing was also performed. Hearing evaluations utilized the AUDERA (GSI, Eden Prairie, MN) device for DPOAE and ABR threshold measurements. Each test was conducted in an acoustic room with naturally sleeping infants, without the use of sedation. The DPOAE tests covered frequency ranges from 250 to 8000 Hz. The pass criteria for the OAE machine required an SNR value of 3 dB across all four frequencies tested or 5 dB in three out of the four frequencies (38, 39).

In ABR testing, alternating click stimuli of 0.1 milliseconds were used. The acceptable inter-electrode impedance was maintained under 2 kilo-ohms, with the desired electrode impedance being less than 5 kilo-ohms. The intensity of the ABR test started at 60 dB nHL and was decreased in 10 dB steps. Wave V was identified twice at the lowest response level, which was defined as the ABR threshold.

4. Results

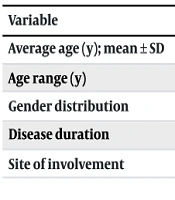

In this study, statistical analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between VEO-IBD and hearing function, considering various factors (Table 1). The analysis focused on as shown in Table 1.

| Variables | CD (n = 12) | UC (n = 14) | Total (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (y); mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | - |

| Age range (y) | 0 - 6 | 0 - 6 | - |

| Gender distribution | 7 males, 5 females | 8 males, 6 females | 13 males, 12 females |

| Disease duration | - | - | Acute: < 6 months, chronic: 6 months to 2 years, long-term: > 2 years |

| Site of involvement | Colon, ileum | Colon, ileum | - |

Abbreviations: n, number of patients; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

4.1. Subgroup Analysis

4.1.1. Disease Duration and Phase

Patients were categorized into three phases: Acute (less than 6 months), chronic (6 months to 2 years), and long-term (more than 2 years). No significant differences in hearing function were observed among these subgroups.

4.1.2. Disease Type

Patients with CD and UC were analyzed separately. The average age for CD patients was 3.5 years (SD = 1.2), while for UC patients, it was 4.0 years (SD = 1.5). The gender distribution included 7 males and 5 females for CD and 8 males and 6 females for UC. Despite these differences, no significant variation in hearing function was observed between disease types.

4.1.3. Site of Involvement

Analysis based on the specific gastrointestinal sites affected (colon or ileum) revealed no significant differences in hearing status.

4.1.4. Age and Gender Distribution

The average age and standard deviation were calculated for each subgroup, and gender distribution was recorded. These factors were considered to ensure a comprehensive understanding and facilitate comparison with control data.

4.2. Statistical Testing

Independent t-tests were conducted to compare hearing function between the VEO-IBD group and the control group. The analysis showed no significant difference in hearing thresholds (P ≥ 0.01) between the two groups. This included assessments of DPOAE and ABR (Table 2).

| Test Type | VEO-IBD Group | Control Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPOAE | No significant difference | - | ≥ 0.01 |

| ABR | No significant difference | - | ≥ 0.01 |

Abbreviations: VEO-IBD, very early onset inflammatory bowel disease; DPOAE, distortion product otoacoustic emissions; ABR, auditory brainstem responses.

These analyses confirm that VEO-IBD did not exhibit a significant association with subclinical hearing loss in the studied cohort. Further research with larger sample sizes and more diverse populations may provide deeper insights into potential late-onset auditory issues and help validate these findings.

5. Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the potential relationship between VEO-IBD and subclinical hearing loss in a pediatric population. In this study, we did not observe subclinical hearing loss among patients with VEO-IBD. Few studies have examined subclinical hearing loss in IBD patients. McCabe was the first to describe immune-mediated SNHL, reporting 18 patients who responded to immunosuppressive therapy and one case involving vasculitis in the middle ear and mastoid tissue (40). Akbayir et al. demonstrated that both CD and UC could be associated with SNHL (28). Patients with CD may experience the sudden onset of typical SNHL, and subclinical auditory disorders may accompany this type of bowel disease (41, 42). Kumar et al. found that 20 patients with active UC exhibited SNHL across all frequencies compared to a control group (37). In the study by Wengrower et al., hearing loss was observed in 38% of patients with IBD, with the prevalence increasing to 52% in those with EIM (43).

Only one study has demonstrated a correlation between VEO-IBD and SNHL. This study identified variants in the STXBP3 gene as being associated with VEO-IBD, SNHL, and immune dysregulation. The research describes a novel genetic syndrome and highlights the critical role of STXBP3 in the development of these conditions (32).

Immune-mediated mechanisms are thought to be responsible for hearing loss in IBD. The immune response associated with SNHL is believed to involve T lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity, vasculitis, and immune complex deposition (36, 44). Damage to the organ of corti may result from delayed cell-mediated hypersensitivity. A temporal biopsy of a UC patient supported a cytotoxic etiology, showing lymphocyte infiltration and migration deterrence (40, 45).

The pathogenesis of EIM of IBD is not well understood, but increased bowel permeability during active disease may expose the systemic immune system to luminal antigens. Activation of the immune system and the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-12 may lead to significant inflammatory consequences elsewhere (46). The IBD can trigger autoimmune attacks on the inner ear and other extraintestinal sites. Unlike sudden, symptomatic SNHL that occurs during active bowel disease phases, subclinical hearing loss may develop independently of disease activity and remain undetected.

According to Loft et al.'s paper (47) and Akbayir et al.’s study (48), SNHL is not associated with bowel disease activity in IBD patients, regardless of the degree of inflammation. Conversely, Kumar et al. found that subclinical hearing loss correlated positively with bowel disease activity across all frequencies (37). However, their study excluded patients with low disease activity or complete recovery, which may have limited their ability to substantiate their claim that bowel disease activity is directly associated with hearing loss.

The detailed breakdown of age and gender by disease type helps contextualize the study's findings and provides a basis for comparison with similar studies. For instance, studies by Loft et al. (47) and Akbayir et al. (48) have reported varying age and gender distributions in IBD patients, contributing to a broader understanding of how these factors might correlate with hearing loss in different patient populations.

The potential link between hearing loss and medications commonly used to treat IBD, such as steroids, mesalamine, and azathioprine, was also investigated. Although these drugs could theoretically contribute to auditory disturbances, statistical analysis in this study revealed no significant association between drug intake and hearing loss (28).

After evaluating infants diagnosed with VEO-IBD, no signs of hearing loss were observed post-treatment. The disparity between our findings and previous studies may be due to differences in the age of onset of IBD. Earlier studies focused on adult-onset IBD, where the disease may exert a more pronounced or different impact on auditory function. Our study focused on VEO-IBD, which affects very young children, potentially explaining the lack of significant hearing impairment. This distinction suggests that the age of onset and disease duration could play crucial roles in the manifestation of extraintestinal symptoms like hearing loss.

Both subclinical and sudden hearing loss have been reported in IBD cases. Subclinical hearing loss refers to subtle auditory dysfunctions detectable through advanced audiological tests, while sudden hearing loss presents as an acute and noticeable impairment. Given these variations, further research incorporating additional variables and diverse patient groups could provide more conclusive insights. Although VEO-IBD did not affect the hearing status of the studied group, future studies should explore whether age, disease progression, or treatment interventions play a role in auditory health outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

There have been reports of sudden SNHL due to autoimmune mechanisms associated with IBD. However, in this study, the occurrence of VEO-IBD did not result in hearing loss among affected children.